Traumatic Axonal Injury: Atlas of Major Pathways

Identification of TBI, particularly mild TBI, is often quite challenging. The most common type of injury, and the most likely injury to occur in mild TBI, is traumatic axonal injury (also called diffuse axonal injury). 18 While magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive than computed tomography (CT) in detecting this type of brain injury, even MRI is often negative. 18 – 23 In addition, some areas of injury may become less visible with time. 21 In such cases, MRI in the subacute and chronic stages is less likely to be positive than if acquired immediately following injury. There is increasing evidence that functional imaging (e.g., cerebral blood flow, cerebral metabolic rate) may be considerably more sensitive to the effects of TBI than structural imaging. 23 – 27

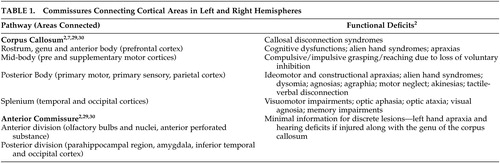

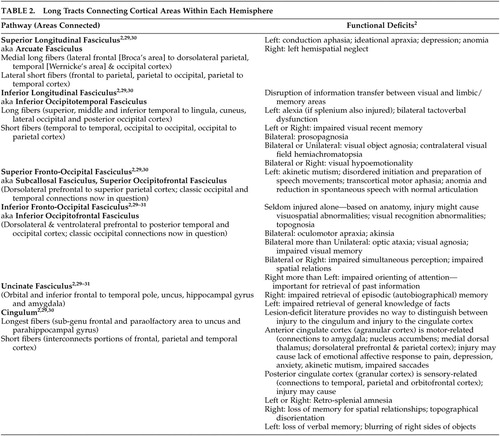

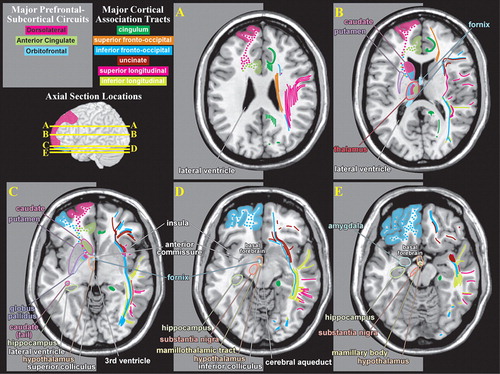

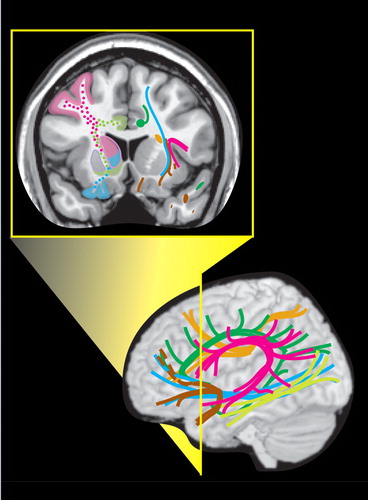

Even small areas of injury within the white matter may have devastating consequences. Knowledge of the locations of major tracts and the brain areas they interconnect is thus critical for understanding clinical symptoms in the context of TBI. White matter tracts of particular importance in neuropsychiatry include those interconnecting areas of cortex (e.g., corpus callosum, association fiber tracts), those connecting areas of cortex to subcortical structures critical for cognitive/emotional functions (e.g., thalamic radiations) and those interconnecting these subcortical areas (e.g., fornix). 2 , 28Tables 1 to 3 summarize the classic functional anatomy of the major white matter pathways important for cognitive and emotional functioning ( Figure 1 ). They are based on recent studies delineating the anatomy of white matter in humans, primarily using diffusion tensor imaging. 1 , 2 , 6 – 8 , 29 – 33

|

|

|

Intriguing results from sophisticated radioisotope tract-tracing studies in nonhuman primates suggests that there may be significant errors in the classic view of cerebral white matter. 34 , 35 For example, this work has delineated three different components (in both location and areas connected) of the superior longitudinal fasciculus. A fourth pathway, which this research group considered to be the arcuate fasciculus, was also identified. A recent diffusion tensor imaging study 36 supports the existence of all four of these pathways in humans. Methods for delineating connections within the intact brain are undergoing rapid development and refinement. It is extremely likely that over the next decade, our understanding of the pathways within the brain that are important for cognitive and emotional functioning will change dramatically.

CONCLUSIONS

Care must be taken in applying this summary of functional anatomy to individual patients, as studies comparing pathway topography between subjects have shown considerable normal variability ( Figure 2 ). 6 – 8 This is parallel to the normal variation in size, shape, and location of Brodmann’s areas ( Figure 2 ). 3 – 5 This known phenomenon adds a distinct level of uncertainty in predicting individual functional deficits following a brain injury. It should also be kept in mind that in many places multiple pathways travel close together, making it likely that a TBI will affect more than one and produce complex symptom clusters. These symptoms may not become evident for extended periods of time. Atlases and other visual external memory aids can assist clinicians in rapid memory recall of functional circuits and areas for review on patient imaging examinations.

1. Mori S, Wakana S, Nagae-Poetscher LM, et al: MRI Atlas of Human White Matter. New York, Elsevier, 2005Google Scholar

2. Aralasmak A, Ulmer JL, Kocak M, et al: Association, commissural, and projection pathways and their functional deficit reported in literature. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2006; 30:695–715Google Scholar

3. Amunts K, Malikovic A, Mohlberg H, et al: Brodmann’s areas 17 and 18 brought into sterotaxic space: where and how variable? Neuroimage 2000; 11:66–84Google Scholar

4. Amunts K, Weiss PH, Mohlberg H, et al: Analysis of neural mechanisms underlying verbal fluency in cytoarchitectonically defined stereotaxic space—the roles of Brodmann areas 44 and 45. Neuroimage 2004; 22:42–56Google Scholar

5. Uylings HB, Rajkowska G, Sanz-Arigita E, et al: Consequences of large interindividual variability for human brain atlases: converging macroscopical imaging and microscopical neuroanatomy. Anat Embryol 2005; 210:431Google Scholar

6. Burgel U, Amunts K, Hoemke L, et al: White matter fiber tracts of the human brain: three-dimensional mapping at microscopic resolution, topography and intersubject variability. Neuroimage 2006; 29:1092–1105Google Scholar

7. Hofer S, Frahm J: Topography of the human corpus callosum revisited—comprehensive fiber tractography using diffusion tensor MRI. Neuroimage 2006; 32:989–994Google Scholar

8. Zarei M, Johansen-Berg H, Smith S, et al: Functional anatomy of interhemispheric cortical connections in the human brain. J Anat 2006; 209:311–320Google Scholar

9. Murray CK, Reynolds JC, Schroeder JM, et al: Spectrum of care provided at an Echelon II medical unit during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Mil Med 2005; 170:516–520Google Scholar

10. Gondusky JS, Reiter MP: Protecting military convoys in Iraq: an examination of battle injuries sustained by a mechanized battalion during Operation Iraqi Freedom, II. Mil Med 2005; 170:546–549Google Scholar

11. Okie S: Traumatic brain injury in the war zone. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2043–2047Google Scholar

12. Warden DL, Ryan LM, Helmick KM, et al: War neurotrauma: the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) experience at Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC). J Neurotrauma 2005; 22:1178Google Scholar

13. Schwab KA, Baker G, Ivins BJ, et al: The Brief Traumatic Brain Injury Screen (BTBIS): investigating the validity of a self-report instrument for detecting traumatic brain injury (TBI) in troops returning from deployment in Afghanistan and Iraq. Neurology 2006; 66:A235Google Scholar

14. Warden D: Military TBI during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2006; 21:398–402Google Scholar

15. Ivins BJ, Schwab KA, Warden D, et al: Traumatic brain injury in U.S. Army paratroopers: prevalence and character. J Trauma 2003; 55:617–621Google Scholar

16. Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Wald MM: The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2006; 21:375–378Google Scholar

17. Drake AI, McDonald EC, Magnus NE, et al: Utility of Glasgow Coma Scale–Extended in symptom prediction following mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2006; 20:469–475Google Scholar

18. Hurley RA, McGowan JC, Arfanakis K, et al: Traumatic axonal injury: novel insights into evolution and identification. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 16:1–7Google Scholar

19. Gutierrez-Cadavid JE: Imaging of head trauma, in Imaging of the Nervous System. Edited by Latchaw RE, Kucharczyk J, Moseley ME. Philadelphia, Elsevier Mosby, 2005, pp 869–904Google Scholar

20. Le TH, Gean AD: Imaging of head trauma. Semin Roentgenol 2006; 41:177–189Google Scholar

21. Brandstack N, Kurki T, Tenovuo O, et al: MR imaging of head trauma: visibility of contusions and other intraparenchymal injuries in early and late stage. Brain Inj 2006; 20:409–416Google Scholar

22. Kurca E, Sivak S, Kucera P: Impaired cognitive functions in mild traumatic brain injury patients with normal and pathologic MRI. Neuroradiology 2006; Jun 20 [e-pub ahead of print]Google Scholar

23. Shin YB, Kim SJ, Kin IJ, et al: Voxel-based statistical analysis of cerebral blood flow using technetium-99m ECD brain SPECT in patients with traumatic brain injury: group and individual analyses. Brain Inj 2006; 20:661–667Google Scholar

24. Barkai G, Goshen E, Tzila Zwas S, et al: Acetazolamide-enhanced neuroSPECT scan reveals functional impairment after minimal traumatic brain injury not otherwise discernible. Psychiatry Res 2004; 132:279–283Google Scholar

25. Gowda NK, Agrawal D, Bal C, et al: Technetium tc-99m ethyl cysteinate dimer brain single-photon emission CT in mild traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27:447–451Google Scholar

26. Shiga T, Ikoma K, Katoh C, et al: Loss of neuronal integrity: a cause of hypometabolism in patients with traumatic brain injury without MRI abnormality in the chronic stage. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2006; 33:817–822Google Scholar

27. Pavel D, Jobe T, Devore-Best S, et al: Viewing the functional consequences of traumatic brain injury by using brain SPECT. Brain Cogn 2006; 60:211–213Google Scholar

28. Tekin S, Cummings JL: Frontal-subcortical neuronal circuits and clinical neuropsychiatry: an update. J Psychosom Res 2002; 53:647–654Google Scholar

29. Catani M, Howard RJ, Pajevic S, et al: Virtual in vivo interactive dissection of white matter fasciculi in the human brain. Neuroimage 2002; 17:77–94Google Scholar

30. Jellison BJ, Field AS, Medow J, et al: Diffusion tensor imaging of cerebral white matter: a pictorial review of physics, fiber tract anatomy, and tumor imaging patterns. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25:356–369Google Scholar

31. Kier EL, Staib LH, Davis LM, et al: MR imaging of the temporal stem: anatomic dissection tractography of the uncinate fasciculus, inferior occipitofrontal fasciculus, and Meyer’s loop of the optic radiation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25:677–691Google Scholar

32. O’Donnell LJ, Kubicki M, Shenton ME, et al: A method for clustering white matter fiber tracts. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27:1032–1036Google Scholar

33. Heiervang E, Behrens TE, Mackay CE, et al: Between session reproducibility and between-subject variability of diffusion MR and tractography measures. Neuroimage 2006; 33:867–877Google Scholar

34. Schmahmann JD, Pandya DN: Fiber Pathways of the Brain. New York, Oxford University Press, 2006Google Scholar

35. Schmahmann JD, Pandya DN, Wang R, et al: Association fibre pathways of the brain: parallel observations from diffusion spectrum imaging and autoradiography. Brain 2007 (e-pub ahead of print)Google Scholar

36. Makris N, Kennedy DN, McInerney S, et al: Segmentation of subcomponents within the superior longitudinal fascicle in humans: a quantitative, in vivo, DT-MRI study. Cerebral Cortex 2005; 15:854-869Google Scholar

37. Zarei M, Johansen-Berg H, Jenkinson M, et al: Two-dimensional population map of cortical connections in the human internal capsule. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007; 25:48–54Google Scholar

38. Nolte J: The Human Brain. St. Louis, Mosby, 2002Google Scholar