A Diffuse Brain Injury Leading to a Complex Neurobehavioral Syndrome

To the Editor: We report on a 22-year-old female without prior psychiatric history had a subarachnoid hemorrhage from an intracranial aneurysm in the junction between the posterior left communicating artery and the left carotid artery during a clipping procedure. Three months later, focal signs were improved but parkinsonism and interpersonal difficulties emerged. Concomitantly, the patient had repetitive stereotyped movements consisting of hand flapping, finger snapping very close to her ear, alternating from right to left, ordering, and touching compulsions. She reported a “feeling” that something “bad” might happen otherwise. Neurological exam was remarkable for bilateral patellar hyperreflexia, clonus, and mento-palmar reflex. A neuropsychological evaluation showed lack of impulse control, marked aggressive tendencies, and a high level of anxiety. She had anterograde amnesia and attentional problems due to errors of omission and perseverance in vigilance capacity.

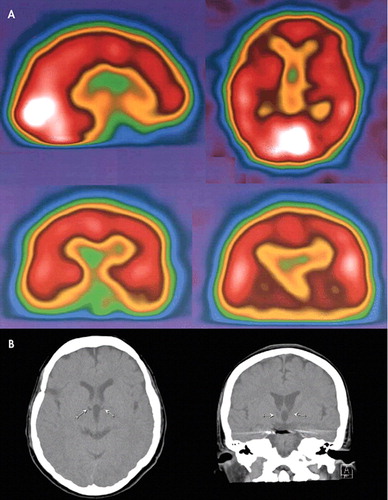

Two years after the hemorrhage, with persisting symptoms, a spiral computerized tomography scan (CT) evidenced asymmetric frontal lobes and two hypodense thalamic small cystic areas, suggesting ischemic events. A single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan at rest showed partial loss of brain asymmetry with global hypoperfusion including the thalamus, premotor cortex, mesial orbitofrontal and dorsolateral cortex, and basal ganglia bilaterally. Hyperperfusion was observed in Brodman area 6, temporal lobes, anterior cingulum, and parietal lobes (L > R) ( Figure 1 ).

Discussion

Cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) circuits that originate in the prefrontal cortex and traverse the striatum and thalamus to then return again to prefrontal cortex have been implicated in the pathogenesis of emotional and behavioral disorders. Disruption of these circuits has been linked to the emergence of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms and movement disorders. 1 This patient presents a complex neurobehavioral syndrome which is a confluence of compulsive, impulsive and disinhibition symptoms, reminiscent of the comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder, Tourette syndrome, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) that is present in some children with neurodevelopmental disorders. 3 While in those children the etiology is “neurodevelopmental” in origin, in our patient the condition was acquired due to extensive lesions in the cerebrum suggesting that the underlying deficits in children with concurrent OCD, Tourette syndrome, and ADHD may be equally global in nature and nonfocal. Findings in the patient’s CT and SPECT, which included two small thalamic necrotic areas and hypoperfusion of the right orbitofrontal cortex, the striate, and thalamus, may explain disruption in the cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical associated with OCD 2 and stereotypies. 3 Hyperperfusion of the anterior cingulum appreciated in the SPECT has been associated to indecision and doubt present in OCD and in this patient. 4 Finally, the patient had touching compulsions which are reminiscent of an “environmental dependency” syndrome which may respond to fronto-parietal disconnections as evidenced in the SPECT, and correspond to the touching compulsions seen in children with OCD and Tourette syndrome. 5 The confluence of compulsive, impulsive, and disinhibition symptoms in a single patient with multifocal acquired brain lesions may signal the type of diffuse abnormality that might be present in children with comorbid neurodevelopmental disorders such as OCD, Tourette syndrome, and ADHD.

1 . Palumbo D, Maughan A, Kurlan R: Hypothesis III: Tourette syndrome is only one of several causes of a developmental basal ganglia syndrome. Arch Neurol 1997; 54:475–483Google Scholar

2 . Busato GF, Zamignani DR, Buchpiguel CA, et al: A voxel-based investigation of regional cerebral blood flow abnormalities in obsessive–compulsive disorder using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 2000; 99:15–27Google Scholar

3 . Maraganore DM, Lees AJ, Marsden CD: Complex stereotypies after right putaminal infarction: a case report. Mov Disord 1991; 6:358–361Google Scholar

4 . Sachdev PS, Malhi GS: Obsessive-compulsive behaviour: a disorder of decision-making. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2005; 39:757–763Google Scholar

5 . Lhermitte F: Human autonomy and the frontal lobes, part II: patient behavior in complex and social situations: the “environmental dependency syndrome.” Ann Neurol 1986; 19:335–343Google Scholar