Depressed Mood and Memory Impairment Before and After Unilateral Posteroventral Pallidotomy in Parkinson’s Disease

Advances in neurosurgical techniques have made it possible to produce marked improvements in the motor impairments characteristic of medically refractory Parkinson’s disease. 6 Although deep brain stimulation has gradually replaced pallidotomy as the procedure of choice in North America and Europe, posteroventral pallidotomy is still widely performed in many parts of the world because it is effective, is much less costly, and does not require laborious programming. Unilateral posteroventral pallidotomy interrupts the neural circuitry believed to be responsible for the abnormally patterned motor activity in frontostriatal circuitry by lesioning the internal segment of the globus pallidus. After posteroventral pallidotomy, variable cognitive outcomes have been reported. 7 These variable results may partly reflect changes in motor functioning after surgery or surgical lesioning outside of motor tracts into more anterior or external portions of the globus pallidus. 8 However, one proposal that has not been explored to explain the variability in cognition after posteroventral pallidotomy is poor mood state.

Previous research indicates an association between impaired verbal memory and depressed mood in individuals diagnosed with major depression. 9 The relationship between depressed mood and memory impairment has also been demonstrated in patients who traditionally present in neurology clinics, including individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, 10 multiple sclerosis, 11 stroke, 12 and traumatic brain injury. 13 In individuals with Parkinson’s disease, the presence of depressed mood is related to poor encoding and retrieval of new information. 14 – 18 Surgical intervention for treatment of motor impairments provides a unique opportunity to test the premise that restoring more normal activity to the frontostriatal circuits will lead to improvements in mood state, which may in turn lead to improved cognition. 19 , 20

To date, no study has assessed the relationship between depressed mood and verbal recall ability after posteroventral pallidotomy. The goal of the present study was to evaluate poor mood state as a moderator of change in verbal recall ability from before to after posteroventral pallidotomy surgery using repeated-measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Motor disease severity was included as a covariate to control for the dual association that motor symptom severity has with both verbal memory and depressed mood. 21 , 22 We also included side of surgery as a potential moderator variable given that previous research suggests that a different pattern of cognitive impairment exists based on the side of prominent motor symptoms. 23

METHOD

Participants

A retrospective analysis was performed on a series of patients who underwent unilateral posteroventral pallidotomy to relieve motor impairments associated with advanced, medically refractory Parkinson’s disease. Subjects were recruited from the Baylor College of Medicine Parkinson’s Disease Center and Movement Disorders Clinic from 1995 to 2000. Fifty-four subjects (31 left-posteroventral pallidotomy, 23 right-posteroventral pallidotomy; 26 women, 28 men) were selected whose clinical findings were consistent with Parkinson’s disease (e.g., patients with dystonia excluded) and had both pre- and postsurgery memory and mood state data. Subjects who were included in the study because they had follow-up data did not differ significantly in chronological age, level of education, duration of illness or age at onset of disease, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor scores or Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores compared to subjects who were excluded from the study. All 54 subjects had a history of response to L -dopa therapy and all subjects had evidence of advanced disease based on disabling motor fluctuations, L -dopa induced dyskinesias or freezing, and a Hoehn and Yahr Parkinson’s disease staging score of 3 or more during periods of medication withdrawal (“off” period). 24 No subject had a Hoehn and Yahr score of 5 during the “on” period. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and the Institutional Review Board of the Baylor College of Medicine approved the research.

Surgical Procedure

Unilateral posteroventral pallidotomy was performed contralateral to the side of the body most affected by motor symptoms. Stereotactic CT guidance, microelectrode recording, and macrostimulation were used to determine the optimal site of the lesion within the internal segment of the globus pallidus. A detailed description of our surgical procedure has been published. 25 All surgeries were conducted by one neurosurgeon (RGG).

Neurological Evaluation

Patients were evaluated by movement disorder specialists (JJ, ECL) during the “on” and “off” periods of medication using a modified core assessment program for Intracerebral Transplantation Protocol, including the Hoehn and Yahr staging scale, the Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scale, the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, and additional examinations. 26 Full details of the neurological evaluations have been described elsewhere. 24 Subscale-III of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale was used to represent motor disease severity.

Memory and Mood State Evaluation

Measures of verbal learning and memory were assessed using the California Verbal Learning Test (sum of learning across trials 1–5 and delayed recall score) and the Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised (WMS-R) Logical Memory subtest (immediate and delayed recall scores). The evaluation was conducted while patients were in their best “on” period of medication. Patients received scheduled dosage of their medications throughout testing, and the test administration followed standardized procedures. 27 The BDI was used to quantify the presence of depressive symptoms. Previous research has indicated that the BDI is a valid and reliable measure of depressed mood, with maximum discrimination of significant symptoms of depression using a cutoff score of 13 28 in order to remove the positive endorsement of physical features associated with both depression and Parkinson’s disease. Group sample sizes when dividing patients by side of surgery (left, right) and mood state (defined as a presurgery BDI cutoff score >12) were as follows: left-posteroventral pallidotomy patients with (N=11) and without depressed mood (N=20) and right-posteroventral pallidotomy patients with (N=11) and without depressed mood (N=12). Neuropsychological testing was conducted by one of two clinical neuropsychologists (MKY, HSL). All patients were tested approximately 3 months after surgery.

Statistical Analyses

Repeated-measures (presurgery, postsurgery) ANCOVAs were conducted for each memory measure with side of surgery (left, right) and mood state (depressed, not depressed) as between-subject factors covarying for motor disease severity. Presurgery post hoc comparisons, as well as postsurgery post hoc comparisons, were conducted for any significant interactions or main effects. Tukey’s honestly significant difference test was used for all post hoc comparisons. Effect sizes (η p2 ) were reported using guidelines recommended by Green and Salkind 29 for interpretation: 0.01 represents a small effect size, above 0.06 a medium effect size, and above 0.14 a large effect size. Raw scores were used in all analyses calculated with SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill).

RESULTS

Descriptives

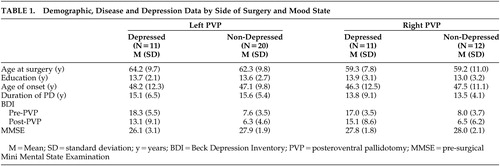

There were no missing data. We found no out-of-range values, skewed distributions, and kurtotic distributions. There were no significant between-group differences on any of the demographic and disease-related variables ( Table 1 ). Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores are also presented in Table 1 . The left-posteroventral pallidotomy group had a significantly lower MMSE score (F=3.87, df=1, 50, p<0.05) compared to all other groups. The group mean presurgery memory scores (not shown) were compared to age-based published norms and found to be within the below average range for all California Verbal Learning Test and WMS-R Logical Memory indices (between the 24th and 10th percentile ranks). There was no difference in the time of testing after surgery between groups (i.e., all patients were tested approximately 3 months postsurgery).

|

Mood State and Motor Disease Severity Before and After Surgery

Repeated-measures ANOVA (presurgery, postsurgery) with BDI scores as the dependent variable indicated no significant two-way interaction ( Table 1 ). There was a significant main effect for time (Hotellings Trace F=4.50, df=1, 52, p<0.05) indicating a significantly improved mood state for the group regardless of side of surgery. Repeated-measures (presurgery, postsurgery) multivariate analysis of variance (mood state × side of surgery), with motor disease severity “on” and “off” periods of medication as the dependent variables, indicated no significant three-way or two-way interactions. A significant time main effect was found for “on” periods of medication (within-subject F=8.24, df=1, 50, p<0.01) and “off” periods of medication (within-subject F=24.16, df=1, 50, p<0.001) indicating significant improvement in motor scores from pre- to postsurgery. There was also a significant between-subject mood state main effect for “off” periods of medication (between-subject F=4.00, df=1, 50, p<0.05) such that subjects with depressed mood had more severe motor disease ratings after surgery compared to subjects without depressed mood (depressed mood Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale score =39.2, nondepressed mean =32.7). There were no other significant main effects.

Relationship Among Verbal Memory, Mood State, and Side of Surgery

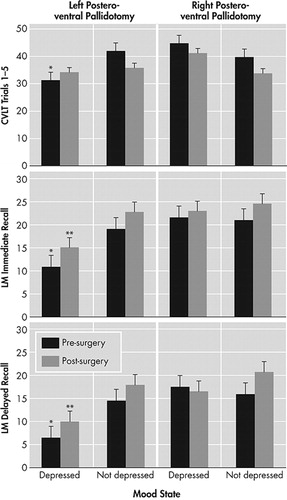

Repeated-measures (presurgery, postsurgery) ANCOVA (side of surgery × mood state) with California Verbal Learning Test trials 1–5 as the dependent variable indicated no significant three-way interactions ( Figure 1a ). A significant side of surgery (left, right) × mood state (depressed, not depressed) interaction was found (F=4.07, df =1, 49, p<0.05, η p2 =0.08). Post hoc analyses indicated that left-posteroventral pallidotomy subjects with depressed mood consistently performed more poorly compared to all other groups before surgery (Tukey’s honestly significant difference p<0.05). There were no other significant interactions or main effects. Repeated-measures ANCOVA with California Verbal Learning Test delayed recall as the dependent variable indicated no significant three-way interaction, two-way interactions, or main effects.

Figure 1a, 1b, 1c. Shows the side of surgery (left, right) × mood state (depressed, not depressed) interaction for the memory tasks demonstrating that depressed left-PVP patients performed poorer compared to other groups before surgery (CVLT and LM) and after surgery (for LM immediate and delayed recall).

*Significant post hoc analysis (p<0.05) compared to other pre-surgery data

**Significant post hoc analysis (p<0.05) compared to other post-surgery data

LM=Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised Logical Memory; CVLT=California Verbal Learning Test; PVP=posteroventral pallidotomy

Repeated-measures (presurgery, postsurgery) ANCOVA (side of surgery×mood state) with WMS-R Logical Memory immediate recall as the dependent variable indicated no significant three-way interaction ( Figure 1b ). A significant side of surgery (left, right) × mood state (depressed, not depressed) interaction was found (F=4.35, df=1, 49, p<0.05, η p2 =0.09). Post hoc analyses indicated that left-posteroventral pallidotomy subjects with depressed mood consistently performed poorer compared to all other groups both before surgery and after surgery (Tukey’s honestly significant difference in all cases p<0.05). In general, all groups improved in WMS-R logical memory immediate recall ability from pre- to postsurgery. There were no other significant interactions or main effects.

Repeated-measures (presurgery, postsurgery) ANCOVA (side of surgery × mood state) with WMS-R Logical Memory delayed recall as the dependent variable showed a similar pattern of results that was found for WMS-R Logical Memory immediate recall ( Figure 1c ). Specifically, a significant side of surgery (left, right) × mood state (depressed, not depressed) interaction was found (between-group F=4.78, df=1, 49, p<0.05, η p2 =0.11). Post hoc analyses indicated that left-posteroventral pallidotomy subjects with depressed mood consistently performed poorer compared to all other groups both before and after surgery (Tukey’s honestly significant difference p<0.05).

Given that left-posteroventral pallidotomy patients had significantly lower presurgical MMSE scores, additional analyses were conducted using the measure of general mental status as a covariate. The pattern of results remained the same: left-posteroventral pallidotomy patients with depressed mood performed significantly poorer on the verbal memory measures with general impairment included as a covariate.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the relationship between depressed mood and verbal recall ability from before to after posteroventral pallidotomy, controlling for motor disease severity. Results indicated that left-sided posteroventral pallidotomy surgical candidates with depressed mood performed poorer on measures of verbal memory, both before and after surgery, compared to left- or right-posteroventral pallidotomy subjects without depression and right-posteroventral pallidotomy subjects with depression. This pattern remained postoperatively. The presence of depressive symptoms in a subset of posteroventral pallidotomy patients may explain the variable results regarding the presence of cognitive impairment found in previous research. The findings are consistent with studies that have found a relationship between depression and verbal memory ability in nonsurgical medically managed Parkinson’s disease patients. 14 – 18 The results suggest that depressed mood should be taken into account when interpreting memory test performance in Parkinson’s disease surgical candidates both before and after surgery.

Similar to findings in individuals with left-sided epileptic seizure foci or left-sided stroke, 30 , 31 we found that left-sided posteroventral pallidotomy surgical candidates with depressed mood had poorer verbal memory abilities compared to all subjects without depressed mood or right-sided surgery patients with depressed mood. The lateralized difference only found for left-posteroventral pallidotomy subjects may reflect the fact that verbal memory is a left hemisphere language-based function. It remains to be determined whether the results would differ if nonverbal memory measures were used. The fact that left-sided posteroventral pallidotomy subjects with depressed mood performed more poorly both before and after surgery suggests that interruption of abnormal globus pallidus output to the thalamus and cortex does not influence the significant relationship between depression and memory functioning. Given this, and the fact that the association between depression and memory continues to exist while controlling for motor symptom severity, the relationship may reflect a more permanent neurobiological phenomenon. Of note, memory impairment was relatively greater on the Logical Memory subtest (a 1–2 learning trial test) both before and after surgery compared to the California Verbal Learning Test (a 5-learning trial test). Though speculative, the performance of Parkinson’s disease patients on the list-learning task may indicate an improved ability to learn with repeated trials minimizing the planning impairments associated with frontostriatal dysfunction.

There are several explanations that might account for a relationship between depression and cognition in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. First, cognitive impairment may promote the presence of depressed mood. For example, the presence of memory problems may lead to restricted activities of daily living and reduced independence, which in turn lead to depressed mood. Second, depressed mood may increase the presence of cognitive impairments. For example, a patient with depressed mood may have greater difficulties directing attentional resources during effortful tasks compared to nondepressed individuals, or they may have covert verbalization of depressive thoughts and rumination that interfere with encoding of memories. The co-occurring behavioral and cognitive impairments likely reflect presurgical dysfunction of frontostriatal neural circuitry. 3 Research indicates reduced cerebral blood flow in areas important for both mood regulation and verbal memory in depressed individuals compared to nondepressed individuals. 32 A likely mechanism may be cortical cholinergic denervation, which is related to level of depressive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease patients with cognitive impairment. 33

There is no agreement on the extent or type of lasting cognitive deficits that result after posteroventral pallidotomy. While some studies have not found any deficits in a variety of neuropsychological domains, 34 , 35 some have reported lasting deficits past 6–12 months, 8 , 36 and others have indicated that the cognitive changes are transient and return to baseline levels in 6–12 months. 37 One reason for the variability is that the extent of surgical lesioning outside of motor tracts into more anterior or external portions of the globus pallidus may lead to cognitive changes. 37 , 38 However, the current findings also suggest that depressive symptomatology may account for some of the variability in findings. For example, pseudodementia, defined as a suppression of cognitive functions due to depression, may produce localized exacerbation of cognitive impairments leading to a misinterpretation of neuropsychological test scores. 39 Consequently, future studies should take clinically significant levels of depressed mood into account when interpreting short- and long-term postsurgical neuropsychological results, for example, with deep brain stimulation surgical candidates.

Results are consistent with other research that indicates an association between greater motor symptom severity and depression in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. 22 The relationship between depressed mood state and more severe motor disease is probably bidirectional such that motor problems may contribute to the existence of depression, and conversely classic symptoms of depression involve slower motor speed abilities. Results suggest that depressed mood is a predictor of poorer response to posteroventral pallidotomy given that subjects with depressed mood had more severe motor disease ratings after surgery compared to subjects without depressed mood.

One limitation of this study is its use of archival data, which potentially introduces selection bias. Thus, replication in a prospective cohort would strengthen extrapolation to other surgical Parkinson’s disease subjects. Future studies should also differentiate subtypes of mood disorders based on DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria. Further, measures such as the BDI are not optimal in patients with a chronic medical illness since some of the symptoms associated with a neurological illness overlap with depressive symptoms, which would inflate the BDI scores and lead to a greater likelihood of a depressed mood diagnosis. Future research should also determine whether depressed patients with left posteroventral pallidotomy have impairments in other cognitive domains compared to nondepressed patients. Future studies could also quantify type and dose of anticholinergic medications when evaluating the relationship between depressed mood and cognition. Finally, it is unclear how our results generalize to patients with new-onset Parkinson’s disease or less severe Parkinson’s disease, as well as to patients who are not good candidates for surgical intervention.

In conclusion, depressed mood was associated with poorer memory test performance. Results support the premise that the side of prominent motor symptom impairment and depression should be taken into account when interpreting neuropsychological test performance in surgical candidates with Parkinson’s disease. Further study of the relationship between depression and neuropsychological performance will improve the accuracy of our assessment of the strengths, weaknesses, and needs of the depressed patient with Parkinson’s disease, as well as lead to more effective interventions.

1 . Slaughter JR, Slaughter KA, Nichols D, et al: Prevalence, clinical manifestations, etiology, and treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:187–196Google Scholar

2 . McPherson S, Cummings JL: Neuropsychological aspects of Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism, in Neuropsychological Assessment of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Edited by Grant I, Adams KM. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996, pp 288–311Google Scholar

3 . Saint-Cyr JA: Frontal-striatal circuit functions: context, sequence and consequence. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2003; 9:103–127Google Scholar

4 . Brown R, Jahanshahi M: Depression in Parkinson’s disease: a psychosocial viewpoint. Adv Neurol 1995; 65:61–84Google Scholar

5 . Robinson RG, Manes F: Elation, mania, and mood disorders: evidence from neurological disease, in Neuropsychology of Emotion. Edited by Borod JC. London, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp 239–268Google Scholar

6 . Espay AJ, Mandybur GT, Revilla FJ: Surgical treatment of movement disorders. Clin Geriatr Med 2006; 22:813–825Google Scholar

7 . York MK, Levin HS, Grossman RG, et al: Neuropsychological outcome following unilateral pallidotomy: a review of the literature. Brain 1999; 122:2209–2220Google Scholar

8 . Rettig GM, York MK, Lai EC, et al: Neuropsychological outcome after unilateral pallidotomy for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 69:326–336Google Scholar

9 . Austin MP, Mitchell P, Goodwin GM: Cognitive deficits in depression: possible implications for functional neuropathology. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:200–206Google Scholar

10 . Hill CD, Stoudemire A, Morris R, et al: Similarities and differences in memory deficits in patients with primary dementia and depression-related cognitive dysfunction. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 5:277–282Google Scholar

11 . Schiffer RB, Caine ED: The interaction between depressive affective disorder and neuropsychological test performance in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:28–32Google Scholar

12 . Kauhanen M, Korpelainen JT, Hiltunen P, et al: Poststroke depression correlates with cognitive impairment and neurological deficits. Stroke 1999; 30:1875–1880Google Scholar

13 . Levin HS, Brown SA, Song JX, et al: Depression and posttraumatic stress disorder at three months after mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2001; 23:754–769Google Scholar

14 . Tröster AI, Stalp LD, Paolo AM, et al: Neuropsychological impairment in Parkinson’s disease with and without depression. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:1164–1169Google Scholar

15 . Norman S, Troster AI, Fields JA, et al: Effects of depression and Parkinson’s disease on cognitive functioning. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002; 14:31–36Google Scholar

16 . Starkstein SE, Bolduc PL, Mayberg HS, et al: Cognitive impairments and depression in Parkinson’s disease: a follow up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990; 53:597–602Google Scholar

17 . Wertman E, Speedie L, Shemesh Z, et al: Cognitive disturbances in parkinsonian patients with depression: possible specific neural basis. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1993; 6:31–37Google Scholar

18 . Youngjohn JR, Beck J, Jogerst G, et al: Neuropsychological impairment, depression, and Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychology 1992; 6:149–158Google Scholar

19 . Lai EC, Jankovic J, Krauss JK, et al: Long-term efficacy of posteroventral pallidotomy in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 2000; 55:1218–1222Google Scholar

20 . Robert-Warrior D, Overby A, Jankovic J, et al: Postural control in Parkinson’s disease after unilateral posteroventral pallidotomy. Brain 2000; 123:2141–2149Google Scholar

21 . Hietanen M, Teravainen H: The effect of age of disease onset on neuropsychological performance in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988; 51:244–249Google Scholar

22 . Cubo E, Bernard B, Leurgans S, et al: Cognitive and motor function in patients with Parkinson’s disease with and without depression. Clin Neuropharmacol 2000; 23:331–334Google Scholar

23 . Tomer R, Levin BE, Weiner WJ: Side of onset of motor symptoms influences cognition in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 1993; 34:579–584Google Scholar

24 . Lai EC, Krauss JK: Indications for pallidal surgery for Parkinson’s disease, in Pallidal Surgery for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. Edited by Krauss JK, Grossman R. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1998, pp 113–120Google Scholar

25 . Krauss JK, Grossman R: Operative techniques for pallidal surgery, in Pallidal Surgery for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. Edited by Krauss JK, Grossman R. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1998, pp 121–133Google Scholar

26 . Langston JW, Widner H, Goetz CG, et al: Core assessment program for intracerebral transplantations (CAPIT). Mov Disord 1992; 7:2–13Google Scholar

27 . Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW: Neuropsychological Assessment, 4th ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 2004Google Scholar

28 . Leentjens AF, Verhey FR, Luijckx GJ, et al: The validity of the Beck Depression Inventory as a screening and diagnostic instrument for depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2000; 15:1221–124Google Scholar

29 . Green SB, Salkind NJ: Using SPSS for Windows and Macintosh: Analyzing and Understanding Data, 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ, Prentice Hall, 2003Google Scholar

30 . Dulay MF, Schefft BK, Fargo JD, et al: Severity of depressive symptoms, hippocampal sclerosis, auditory memory, and side of seizure focus in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2004; 5:522–531Google Scholar

31 . Spalletta G, Guida G, De Angelis D, et al: Predictors of cognitive level and depression severity are different in patients with left and right hemispheric stroke within the first year of illness. J Neurol 2002; 249:1541–1551Google Scholar

32 . Baron MS, Vitek JL, Bakay RA, et al: Treatment of advanced Parkinson’s disease by posterior GPi pallidotomy: 1-year results of a pilot study. Ann Neurol 1996; 40:355–366Google Scholar

33 . Mayberg HS: Frontal lobe dysfunction in secondary depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:428–442Google Scholar

34 . Bohnen NI, Kaufer DI, Hendrickson R, et al: Cortical cholinergic denervation is associated with depressive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonian dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007; 78:641–643Google Scholar

35 . Perrine K, Dogali M, Fazzini E, et al: Cognitive functioning after pallidotomy for refractory Parkinson’s disease (comments). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 65:150–154Google Scholar

36 . Trepanier LL, Saint-Cyr JA, Lozano AM, et al: Neuropsychological consequences of posteroventral pallidotomy for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 1998; 51:207–215Google Scholar

37 . Jahanshahi M, Rowe J, Saleem T, et al: Striatal contribution to cognition: working memory and executive function in Parkinson’s disease before and after unilateral posteroventral pallidotomy. J Cogn Neurosci 2002; 14:298–310Google Scholar

38 . Lombardi WJ, Gross RE, Trepanier LL, et al: Relationship of lesion location to cognitive outcome following microelectrode-guided pallidotomy for Parkinson’s disease: support for the existence of cognitive circuits in the human pallidum. Brain 2000; 123:746–758Google Scholar

39 . McNeil JK: Neuropsychological characteristics of the dementia syndrome of depression: onset, resolution, and three-year follow-up. Clin Neuropsychol 1999; 13:136–146Google Scholar