The Portuguese Who Could No Longer Speak French: Primary Progressive Aphasia in a Bilingual Man

To the Editor: Primary progressive aphasia is characterized by progressive language dissolution, with remarkable sparing of other cognitive domains for at least 2 years. 1 We report a Portuguese-French fluent speaker with primary progressive aphasia, in whom disintegration of his second language (French) preceded that of his native one (Portuguese).

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was seen for speech difficulties. He had no past medical history or known familial disease. He studied Portuguese for 4 years and then went to live in France, where he learned French for 3 years. Afterward, he started working as a locksmith. At age 21 he spent 2 years in Saudi Arabia and Iraq, where he spoke French, and then came back to France until turning 42. He then returned to Portugal. Since early adolescence he was fluent, speaking, reading, and writing in both languages. In the last 12 years he spoke French mainly when visiting his family.

Three years ago he started having difficulty naming objects, first with those rarely used, then with more commonly used ones. This was neglected by his family, who even joked saying, “It is Alzheimer calling!” The first and real cause for concern was 1 year ago; when visited by his French brother-in-law, the patient could not exchange a single word of French. This was so overwhelming as to take him by surprise. Since then he has had more and more difficulty speaking Portuguese, with word-finding pauses interrupting his speech and an increasing use of “it” and “that.” Upon examination he had laborious, effortful, nonfluent, and agrammatic speech, with severe anomia and some repetition and complex-command comprehension difficulties. He read better than he wrote, which he did with some paragraph errors and absent connection particles. He could not name, understand, or write any words in French. When asked to read some common words as “ chien ” or “ maison ,” he read them with a Portuguese accent and without any notion of their meaning.

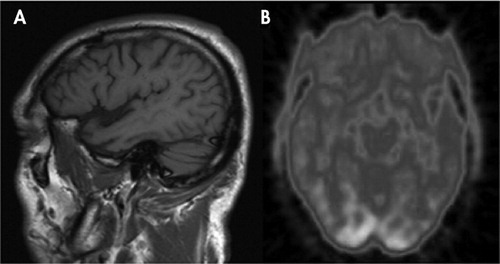

The remaining neurological examination was normal or near-normal considering his age and education level, including his Mini-Mental State Examination score (25/30). A brain MRI showed left-sided temporal cortical atrophy ( Figure 1 , panel A). A PET scan revealed cortical hypometabolism in the temporal lobe, anterior cyngula, and dorsolateral frontal cortex ( Figure 1 , panel B).

A: Left parasagittal T1 weighted image shows disproportionate temporal lobe atrophy.

B: FDG-PET image reveals decreased metabolism in left temporal lobe.

Discussion

Our patient has all clinical, neuropsychological, and imaging features of a nonfluent variant of primary progressive aphasia. 2 The occurrence of primary progressive aphasia in bilinguals can give further insight into the neural network subserving language acquisition and dissolution. 3 It is interesting to note that, in this formerly proficient bilingual, language loss was so overwhelmingly greater in his second and recently less used idiom. In the previously reported bilingual primary progressive aphasia patient, 3 both languages were lost in parallel, with a slight tendency for better preservation of English, which was her second but more recently used language. At least in proficient bilinguals, we believe that the main point on language dissolution in primary progressive aphasia is not the acquisition order but how recently it was used. The best way to confirm this would be to systematically characterize primary progressive aphasia patients on secondary language usage, attained proficiency, and disintegration sequence.

1. Mesulam MM: Primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 2001; 49:425–432Google Scholar

2. Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, et al: Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 2004; 55:335–346Google Scholar

3. Filley CM, Ramsberger G, Menn L, et al: Primary progressive aphasia in a bilingual woman. Neurocase 2006; 12:296–299Google Scholar