Suicide in Patients With Stroke: A Population-Based Study of Suicide Victims During the Years 1988-2007 in Northern Finland

It is well-known that depression is highly associated with suicide. Furthermore, suicidal thoughts after stroke are common; in a follow-up study of 300 patients, up to 11% had suicidal plans during the 2 years following their stroke. 6 A Danish study found that the risk of suicide is strongly increased after stroke, particularly among patients younger than 60 years old and among females. 7 The risk seems to be greatest within the first 5 years after stroke. 8

The impact of poststroke depression on poorer outcomes among stroke patients is well known, 9 – 11 whereas the association between prestroke depression and prognosis among stroke patients has not yet been sufficiently recognized. Recently, a register-based study in the Netherlands with longitudinal data was published in which Nuyen et al. 12 found that patients with prestroke depression had a fivefold risk of being discharged to an institution instead of to their homes compared to patients who were not depressed. However, they did not study the possible effect of depression on the suicide process of these patients.

In this study we used a comprehensive database of all suicides committed in Northern Finland during the years 1988–2007 with information on all hospital-treated somatic and psychiatric disorders. We wanted to find out the following: the prevalence of stroke in suicide victims, whether depression is a risk factor for suicide, and the influence of prestroke depression on suicide process among victims.

METHODS

We examined all suicides (N=2,283) committed during the years 1988–2007 in the province of Oulu in Northern Finland. Data on age, gender, suicide methods, and previous suicide attempts and abuse of alcohol at the time of the suicide were based on the death certificates from forensic medical-legal investigations. The Ethics Committee of Oulu University approved the study protocol. The diagnoses of subjects and hospital admissions of suicide victims were obtained from the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register (FHDR). 13 The FHDR covers all treatment in general, private, mental, military, and prison hospitals, as well as the inpatient wards of local health centers nationwide.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) was used as follows for cerebrovascular diseases: ICD-8 and ICD-9 codes 432–438 and ICD-10 codes I63-I69 and G45. The victims without stroke were dichotomized to two groups as follows: victims younger than 55 years old and those 55 years or older. Based on the epidemiology of stroke prevalence, stroke is known to increase markedly after 55 years old. 14 Psychiatric disorders were categorized as follows: any psychiatric disorder (ICD-8 and ICD-9: 290–319; ICD-10: F00.00-F99) and depression (ICD-8: 2960, 2980, 3004; ICD-9: 2961, 2968, 3004; ICD-10: F32-F34.1).

The methods for suicide among study subjects were categorized as violent if the method was hanging, drowning, shooting, wrist cutting, jumping from a height, and traffic. Nonviolent methods were poisoning, gas, and other methods. Acute alcohol intoxication was detected in the medical autopsy by a doctor in forensic medicine and entered on the death certificate.

Statistical Methods

Statistical significance of group differences in categorical variables was examined with Pearson χ 2 -test or Fisher’s exact test. Cox proportional hazard model was used to examine the likelihood of dying of suicide after stroke in the following three subgroups: prestroke depression, poststroke depression, and no depression after adjusting for age and gender of the victims. All statistical tests were performed with SPSS for Windows, version 13.

RESULTS

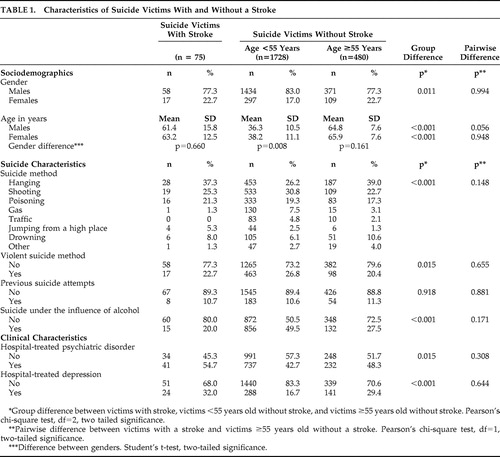

Of the total suicide data population (N=2,283), 3.4% (n=75) had suffered from stroke during their lifetime. Table 1 summarizes the clinical and suicide characteristics of the victims with and without stroke in two different age groups. When comparing the three study groups, statistically significant differences were found in age, gender, suicide method, alcohol contribution to suicide, hospital treated psychiatric disorder, and depression. When comparing the suicide victims with stroke with the age group of 55 years or older, no statistically significant differences were found in pairwise comparisons in the background characteristics.

|

The majority of the victims with stroke (80%) were not under the influence of alcohol at the time of suicide. The most common suicide method among stroke victims was hanging (37.3%); 32% of the victims with stroke had been hospitalized due to their depression ( Table 1 ).

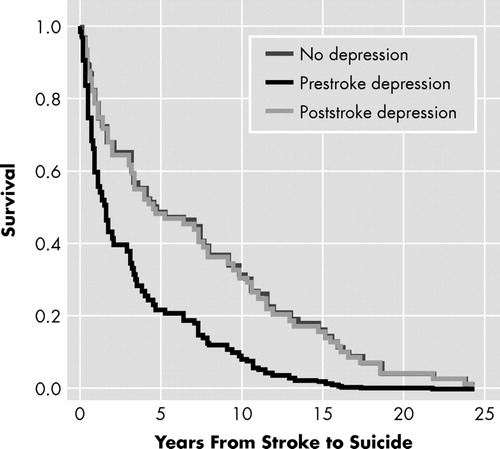

Based on the Cox proportional hazard regressions, Figure 1 presents the survival estimates from stroke to suicide among victims with depression. The age- and sex-adjusted hazard of suicide after stroke was 2.2-fold among victims who had suffered from prestroke depression (adjusted hazard ratio=2.16, 95% CI=1.07–4.37, p=0.033) compared to those without any lifetime depression. The elevated hazard of suicide was not seen among victims with poststroke depression compared to those with prestroke depression (adjusted hazard ratio=1.03, 95% CI=0.56–1.91, p=0.927).

Furthermore, six of the stroke victims whose depression had been assessed before the stroke (55%) committed suicide within 2 years after having a stroke. Correspondingly, only three of the suicide victims with poststroke depression (23%) and 19 of those with no lifetime depression (37%) had committed suicide within 2 years after their stroke.

DISCUSSION

We found that 3.2% of all the subjects in this large population-based suicide data set from Northern Finland had suffered from stroke. Our findings showed a low prevalence of stroke in this suicide database compared to earlier literature. It has previously been shown that the percentage of suicides in persons with stroke may be as high as 7.2% in the Danish population. 7

The suicide victims with stroke were about 63 years old. They were 20 years older and more often female compared to the other victims. Our findings are in line with a former study 7 in which stroke patients in the age groups up to 60 years old and women were shown to have a significantly increased risk of suicide. In general, suicide has been found to be associated with older age and somatic diseases. 15 – 17

The major finding of our study in this suicide data set was that prestroke depression was associated with a significantly shorter survival after stroke. On the other hand, the survival time among victims with poststroke depression did not differ from that of nondepressive ones. Formerly, the timing of depression in relation to stroke was mostly diagnosed as manifesting itself after stroke and thus named poststroke depression. 1 , 4 , 9 – 11 However, it has been shown that one in three stroke patients were using antidepressants at the time when the stroke occurred. 2 It is well known that depression is a recurrent disorder. 18 Thus, it is very likely that depression among stroke patients is not only “poststroke” depression, but a relapse of a recurrent depressive disorder. Poststroke depression has previously been found to associate with poor outcome and quality of life among stroke patients. 9 – 12 To our knowledge, this study is the first one so far in which prestroke depression has been shown to increase the risk of accelerated suicide among stroke patients. It has been suggested that in stroke patients with previous depression, stroke is more severe than in those without prestroke depression, which can also lead to decreased prognosis among stroke patients with depression. 12

In this study about 70% of the stroke victims with prestroke depression had committed suicide within a 2-year period after stroke, compared to 30% of those with no depression or poststroke depression. Earlier, Teasdale and Engberg 8 pointed out that the increased risk period for suicide was 5 years after stroke. However, they did not take into account the possible accelerative effect of depression on the occurrence of suicide. We suggest that the increased risk of suicide should be monitored not only in the long-term follow-up but also particularly during the 2-year period immediately after stroke. Psychiatric consultation is therefore highly recommended for stroke patients with prestroke depression in clinical work at a neurological and neurorehabilitation unit when the follow-up of stroke is being designed. It is well known that recognition of depression and treatment with antidepressive drugs are the most important factors in suicide prevention. 19 , 20

In our study the victims with stroke were significantly more rarely under alcohol intoxication compared to other suicide victims at the time of committing suicide. This finding is interesting since it is known that in general, alcohol intoxication often contributes to suicide. 14 Furthermore, the suicide method among stroke patients was generally nonviolent. According to our findings, we suggest that among stroke patients, suicide is mainly committed without alcohol intake and is thus nonimpulsive and premeditated before the definitive accomplishment of suicide.

In this data set we found that stroke victims had significantly more often suffered from hospital-treated depression compared to the victims without stroke. Former studies have indicated that depression is a major comorbid psychiatric disorder among stroke patients both before and after their stroke. 1 – 4 , 9 – 11 It has also been found that there is a significant association between earlier depressive symptoms and subsequent incidence of stroke. 21 – 23 The direct mechanisms behind this have not yet been clarified. 21 Multiple risk factors have been suggested to contribute to the association between preceding depression and stroke as follows: regulatory failure in the noradrenergic systems, increased adrenergic activity, and disturbances in neuroendocrine or immunology systems. 24 – 27 Further, increased levels of fibrinogen or abnormal platelet activation may lie at least partly behind the association of depression and stroke. 28 – 30 There are also behavioral factors common to both depression and stroke, such as low physical activity, smoking, or an unhealthy diet. 21

As first described by Alexopoulos et al., 31 vascular disease can precipitate, worsen, or complicate depression. The development of depression in the patients with vascular disease is based on a complex set of etiological pathways and interactive factors. 32 Vascular depression has also shown to be associated with executive dysfunction, 33 but the risk of potential increased suicide rates among these patients has not yet been studied.

The limitations of our study were that all diagnoses were obtained from the national register-based information on hospital treatments, and thus only psychiatric disorders severe enough to require hospitalization were analyzed. It is thus possible that the suicide victims may therefore have been treated for mild psychiatric disorders but became disease-free subjects in our study setting. Unfortunately, there are no common national registers for outpatient treatment in Finland, and the percentage of wrongly classified patients, even if small, remains unknown. The number of victims in each subgroup according to depression state was rather small. Also we had no control population, and thus we could not compare the rate of suicides to population based studies. In addition, we were not able to evaluate the severity of stroke in the victims.

The strengths of the present study were that all suicides committed during the study period in the province of Oulu, a geographically large area, were included and evaluated. Thus, the study was limited neither to a certain age group nor to otherwise incomplete suicide data. In addition, the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register has been shown to be a reliable source of information in scientific research on various kinds of hospital treatments of patients. 13

1. Paolucci S: Epidemiology and treatment of post-stroke depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2008; 4:145–154Google Scholar

2. Williams LS: Depression and stroke: cause or consequence? Semin Neurol 2005; 25:396–409Google Scholar

3. Lee HC, Lin HC, Tsai SY: Severely depressed young patients have over five times increased risk for stroke: a 5-year follow-up study. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 15:912–915Google Scholar

4. Hackett ML, Yapa C, Parag VP, et al: Frequency of depression after stroke: a systematic review of observational studies. Stroke 2005; 36:1330–1340Google Scholar

5. Eriksson M, Asplund K, Glader EL, et al: Self-reported depression and use of antidepressants after stroke: a national survey. Stroke 2004; 35:936–941Google Scholar

6. Kishi Y, Robinson RG, Koshier JT: Suicidal plans in patients with stroke: comparison between acute-onset and delayed-onset suicidal plans. Int Psychogeriatrics 1996; 8:623–634Google Scholar

7. Stenager EN, Madsen C, Stenager E, et al: Suicide in patients with stroke: epidemiological study. BMJ 1998; 316:1206Google Scholar

8. Teasdale TW, Engberg AW: Suicide after a stroke: a population study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001; 55:863–866Google Scholar

9. Gainotti G, Antonucci G, Marra C, et al: Relation between depression after stroke, antidepressant therapy, and functional recovery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 71:258–261Google Scholar

10. Narushima K, Robinson RG: Stroke-related depression. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2002; 4:296–303Google Scholar

11. Gaete JM, Bogousslavsky J: Post-stroke depression. Expert Rev Neurother 2008; 8:75–92Google Scholar

12. Nuyen J, Spreeuwenberg P: Impact of preexisting depression on length of stay and discharge destination among patients hospitalized for acute stroke. Stroke 2008; 39:132–138Google Scholar

13. Keskimäki I, Aro S: The accurancy of data on diagnoses, procedures, and accidents in the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register. Int J Health Sci 1991; 2:15–21Google Scholar

14. Kolominsky-Rabas PL, Weber M, Gefeller O, et al: Epidemiology of ischemic stroke subtypes according to toast criteria: incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival in ischemic stroke subtypes: a population-based study. Stroke 2001; 32:2735–2740Google Scholar

15. McGirr A, Seguin M, Renaud J, et al: Gender and risk factors for suicide: evidence for heterogeneity in predisposing mechanisms in a psychological autopsy study. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:1612–1617Google Scholar

16. Waern M, Rubenowitz E, Runeson B, et al: Burden of illness and suicide in elderly people: case-control study. BMJ 2002; 324:1355–1357Google Scholar

17. Koponen HJ, Viilo K, Hakko H, et al: Rates and previous disease history in old age suicide. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007; 22:38–46Google Scholar

18. Robinson OJ, Sahakian BJ: Recurrence in major depressive disorder: a neurocognitive perspective. Psychol Med 2008; 38:315–318Google Scholar

19. Kishi Y, Robinson RG, Kosier JT: Suicidal ideation among patients during the rehabilitation period after life-threatening physical illness. Nerv Ment Dis 2001; 189:623–628Google Scholar

20. Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al: Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005; 294:2064–2074Google Scholar

21. Jonas BS, Mussolino ME: Symptoms of depression as a prospective risk factor for stroke. Psychosomatic Med 2000; 62:463–471Google Scholar

22. Nilsson FM, Kessing LV: Increased risk of developing stroke for patients with major affective disorder: a registry study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 254:387–391Google Scholar

23. Salaycik KJ, Kelly-Hayes M, Beiser A, et al: Depressive symptoms and risk of stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 2007; 38:16–21Google Scholar

24. Carney RM, Freedland KE, Veith RC: Depression, the autonomic nervous system, and coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med 2005; 67(suppl 1):S29–33Google Scholar

25. Surtees PG, Wainwright NW, Luben RN, et al: Psychological distress, major depressive disorder, and risk of stroke. Neurology 2008; 70:788–794Google Scholar

26. Arbelaez JJ, Ariyo AA, Crum RM, et al: Depressive symptoms, inflammation, and ischemic stroke in older adults: a prospective analysis in the cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55:1825–1830Google Scholar

27. Kamphuis MH, Geerlings MI, Dekker JM, et al: Autonomic dysfunction: a link between depression and cardiovascular mortality? The FINE Study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007; 14:796–802Google Scholar

28. Pollock BG, Laghrissi-Thode F, Wagner WR: Evaluation of platelet activation in depressed patients with ischemic heart disease after paroxetine or nortriptyline treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20:137–140Google Scholar

29. Kop WJ, Gottdiener JS, Tangen CM, et al: Inflammation and coagulation factors in persons >65 years of age with symptoms of depression but without evidence of myocardial ischemia. Am J Cardiol 2002; 89:419–424Google Scholar

30. Serebruany VL, Glassman AH, Malinin AI, et al: Sertraline antidepressant heart attack randomized trial study group. Platelet/endothelial biomarkers in depressed patients treated with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline after acute coronary events: the Sertraline AntiDepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) Platelet Substudy. Circulation 2003; 108:939–944Google Scholar

31. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al: “Vascular depression” hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:915–922Google Scholar

32. Baldwin RC: Is vascular depression a distinct sub-type of depressive disorder? A review of causal evidence. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 20:1–11Google Scholar

33. Vataja R, Pohjasvaara T, Mäntylä R, et al: Depression-executive dysfunction syndrome in stroke patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 13:99–107Google Scholar