Emotional Indifference in Alzheimer’s Disease

Sometimes the symptoms of apathy and abulia are confounded because emotional experiences and the knowledge of the conditions that can induce emotions are often sources of motivation. Thus, apathy can contribute to the presence of abulia. Abulia, however, can occur even in the absence of apathy. Many of the behavioral scales and inventories used to assess for apathy, such as Marin’s Apathy Evaluation Scale, have questions about goal oriented behaviors. 7 The Neuropsychiatric Inventory 8 assesses 12 domains, including apathy, but there is no domain labeled as abulia. Further, the question about apathy asks, “Does the patient seem less interested in his or her usual activities… ?” This question is asking about the presence of abulia and not apathy. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease can have disorders of emotional communication. 9 – 11 These problems with emotional communication, as well as abulia, might be responsible for the impression that patients with Alzheimer’s disease are emotionally apathetic. In addition, many emotional experiences are induced by perceiving stimuli and understanding situations. Thus, patients with Alzheimer’s disease might also appear apathetic because they do not understand the circumstances that normally induce emotions.

The purpose of this study was therefore to examine whether patients with Alzheimer’s disease have alterations in their emotional experience as determined by their valence ratings of emotional stimuli (International Affective Picture System). 12 Thus, we had healthy subjects and Alzheimer’s disease subjects make valence judgments by presenting sheets of paper that had happy faces at the proximal end of the paper and sad faces at the distal end (or vice versa in a counterbalanced order).

METHODS

Participants

Seven right-handed subjects who met the McKhann et al. 1984 NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease 1 and eight healthy comparison subjects participated in this study. The mean age of the Alzheimer’s disease patients (four women and three men) was 72.83, SD=12.31, and the mean age of the comparison subjects (seven women and one man) was 59, SD=11.08. Age was not significantly different between the two groups, although we should mention that the age of two comparison subjects was not known. The patients were recruited from the Memory Disorder Clinic at the University of Florida, and the comparison subjects were recruited from the community or were spouses of the patients.

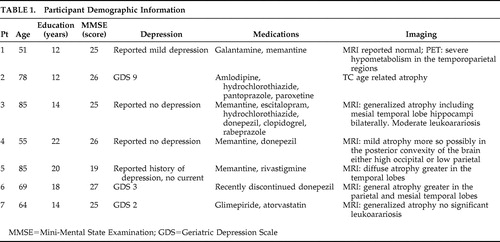

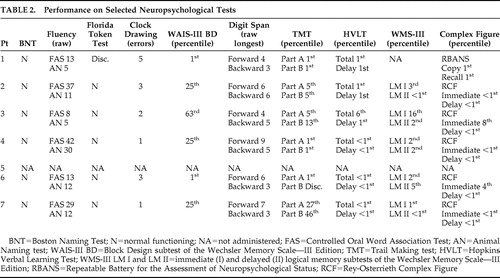

Based on clinical assessments, all subjects were free of any major psychiatric disturbance (i.e., depression or anxiety). Although we did not use a depression scale with all our experimental subjects, we had the opportunity to repeatedly evaluate the same patients over the course of several years, and as part of our clinical evaluation, we routinely ask about symptoms or signs of depression. Based on these clinical evaluations and the use of the Geriatric Depression Scale scores that were available for some of our patients, we are confident that our subjects with Alzheimer’s disease were not suffering with major depression at the time of this study. Subjects also had no history of other neurological diseases. The mean score for the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was 24.71 (SD=2.62) for the subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and 29.5 (SD=0.53) for the comparison participants. (Additional demographic information and information regarding the cognitive status of the Alzheimer’s disease population are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2 .)

|

|

Apparatus and Procedures

This study was approved by our institutional review board, and all subjects provided informed consent. The subjects were asked to judge the pleasantness versus unpleasantness of 20 pictures (10 positive and 10 negative) that were selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS). 12 The IAPS is a commonly used emotional probe that depicts emotion-laden scenes to induce emotional experiences. These pictures have been extensively rated by healthy subjects, and the experimental stimuli were selected on the basis of these normative valence (pleasant/unpleasant) and arousal ratings. The selected pictures portray either emotional facial expressions or emotionally evocative scenes. For example, the unpleasant pictures included vicious animals and violent acts (IAPS numbers: 9340, 9120, 6300, 6200, 2455, 1050, 1220, 1274, 9300, 9050), and the pleasant set included babies, couples, and sports activities (IAPS numbers: 1710, 1750, 2058, 2216, 2340, 5700, 5830, 5621, 4626, 1440). In terms of normative arousal ratings, pleasant and unpleasant pictures were equivalent.

The order of presentation of these pictures was first randomized, and then every other subject received the reverse order of the original set 1–30 and 30–1 to counterbalance for order. The pictures were presented on a table directly in front of the subject.

Each score sheet was 27.9 cm in length and was blank aside from a happy face at one end and a sad face on the other end. The faces were all vertically oriented such that both faces were aligned with the subjects’ midsagittal plane, and one face was above (distal to) the other. The proximal versus distal positions of these sad and happy faces were counterbalanced. Every subject judged 5 out of 10 positive (or negative) pictures with the happy face distal and the other 5 with the happy face proximal, so that a proximal or distal spatial bias would not influence the results of the valence ratings.

All participants were instructed to first look at a picture and judge how pleasant or unpleasant they found the picture. They were then instructed to indicate their judgment by making a mark on the score sheet placed in front of them. If they found the picture pleasant, they should make their mark toward the happy face. If they found the picture unpleasant, they should make their mark toward the sad face. The more pleasant they found this picture, the closer their mark should be to the happy face, and the more unpleasant they found this picture, the closer their mark should be toward the sad face.

After each subject rated all 20 pictures, each of the subject’s marks was measured from the center of the happy or sad face that was congruent with the valence depicted in this picture (the smiling face for the positive pictures, and the sad face for the negative pictures) (XF= distance between the happy or sad face and the mark). Deviations above (distal) and below (proximal to) the actual midline were measured to the nearest 0.5 mm. For the valence ratings, the dependent measures consisted of the distances, in mm, from the appropriate face (“happy” or “sad”) to the participants’ mark (XF).

Analyses

Since the purpose of this study is to learn if patients with Alzheimer’s disease, when compared to comparison subjects, have alterations in their emotional experiences and judgments (valence) or spatial attentional biases, we conducted two separate analyses to assess each of these factors. Regarding valence, the data were analyzed using a 2 (group: Alzheimer’s disease and comparison) × 2 (valence: positive and negative) mixed factorial ANOVA, with group being the between-subjects factor and valence the repeated within-subject factor.

RESULTS

The results indicated no significant main effect for valence and no significant interaction between group and valence. However, the main effect of group was significant (F=5.244, df=1, 13, p=0.039), with the patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease judging the pictures’ valence as less intense (mean=5.82 mm, SD=2.02) than did the comparison subjects (mean=4.25 mm; SD=1.17).

An inconsistent response was defined as placement of mark closer to the face that expressed the emotional valence that was inconsistent (contrary) to the viewed stimulus (picture). For example, if the subject was shown a violent act and subsequently made their response mark closer to the face depicting pleasant emotions (face with a smile), this response would be graded “inconsistent.”

To examine whether the differences in valence judgments were due to impaired comprehension of the instructions or of the pictures, we conducted an analysis of the percentage of consistent responses for both groups. The proportions of consistent scores were calculated by dividing the total number of correct responses by the total number of responses. The results of a 2 (group: Alzheimer’s disease and comparison) × 2 (valence: positive and negative) mixed factorial ANOVA, with group as the between subjects factor and valence as a repeated factor, indicated no significant group × valence interaction. The main effect for valence was also not significant. However, a significant main effect for group was found (F=9.15, df=1, 13, p=0.01). Inspection of the means indicated that the proportion of correct responses for the comparison group (mean=0.98, SD=0.037) was greater than for the Alzheimer’s disease group (mean=0.87, SD=0.095), regardless of the emotional valence.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that when subjects with Alzheimer’s disease are asked to assess the emotional valence of pictures, they judge the pictures that portray pleasant scenes as less pleasant than do the comparison participants, and when they see unpleasant pictures they rate these as less unpleasant than do the comparison subjects. These results suggest that patients with Alzheimer’s disease have a decreased emotional experience and/or responses to seeing emotional scenes. The reason patients with Alzheimer’s disease have a reduced emotional response is not known, but there are several possibilities.

The mean age of the participants with Alzheimer’s disease was higher than that of the comparison subjects. Although it is possible that with aging there is a decrease in the intensity of emotional experiences, Grühn and Scheibe, 13 using the International Affective Picture System (IAPS), demonstrated that older subjects perceived negative pictures as more negative and positive pictures as more positive. Thus, the age of our subject groups could not explain our results. Although we did not have the ages of two of our comparison subjects, in order for the comparison subjects to have a mean age that is greater than that of the experimental group, the two comparison subjects, whose age was not recorded, would have to have a mean age of approximately 115 years. Since this is very unlikely, we doubt that age can be the major determinant of the between-group differences. Future research, however, should address the influences of age, gender, and education level.

Depression often accompanies Alzheimer’s disease, and as mentioned previously, patients with depression might have a reduced emotional response. However, our patients did not clinically manifest depression. In addition, in prior studies when subjects with and without depression were asked to report their emotional experiences to positive and negative pictures, their results revealed significant differences in response to positive images (e.g., less pleasant valence, decreased happiness, increased sadness) but no clear group differences in response to negative stimuli. 14 – 16 We found no significant interactions between group and valence, providing additional support for the postulate that the emotional indifference displayed by our Alzheimer’s disease subjects was not a result of depression.

Since our patients with Alzheimer’s disease had a high rate of consistent responses (87%), the decreased emotional responses could not be explained by an inability of these subjects to understand the directions. We should note, though, that even though the Alzheimer’s disease patients exhibited a high rate of consistent responses, their consistent response rate was lower than that of the comparison subjects (98%). However, the variability in responses between the Alzheimer’s disease patients and the comparison subjects was highly similar. Had the Alzheimer’s disease patients not understood the directions, we would expect greater variability in responding as compared to the comparison subjects. Interactions with the Alzheimer’s disease patients during the study also did not indicate that they had difficulty understanding the task instructions. However, pictures and scenes are complex visual stimuli, whose emotional semantic meaning is extracted through progressive cortical analysis involving widespread association areas. 17 , 18 Patients with Alzheimer’s disease can have deficits of visuospatial analysis including forms of simultanagnosia and object agnosia. Albert et al. 19 found that Alzheimer’s disease patients were impaired in identifying emotions portrayed in drawings and verbal descriptions and claimed that the deficit of these Alzheimer’s disease patients was related to a cognitive defect. If our subjects with Alzheimer’s disease had a sufficient degradation of the systems that mediate visual perception or if our subjects could not derive the meaning of the percepts, we would expect that the subjects with Alzheimer’s disease would make valence errors, where pictures expressing positive valence would be scored as expressing a negative valence and vice versa. To explore this possibility we conducted a post hoc analysis of the percent correct responses. The percent correct scores were calculated by dividing the total number of correct responses by the total number of responses. For example, if a subject was shown a picture of a violent act and marked the response sheet closer to the happy than the sad face, it would be considered an inconsistent response. The results indicated that across the positive and negative valences the proportion of correct responses for the comparison group was greater than for the Alzheimer’s disease group. Given this finding, the possibility exists that the Alzheimer’s disease patients experienced problems with picture comprehension. This comprehension deficit might be due to a mild visual agnosia or a deterioration of semantic-conceptual representations. Although we cannot entirely exclude the possibility that the participants with Alzheimer’s disease had a mild agnosia, the participants had no recognition problems when performing either the Boston Naming Test or the Columbia Naming Test, indicating that they were able to recognize the objects presented in these tests ( Table 2 ). These post hoc observations indicate that it is unlikely that our findings might be related to a visual agnosia. Alternatively, our Alzheimer’s disease subjects may have experienced no problems with picture comprehension but experienced a different emotional response to these pictures.

The reason that patients with Alzheimer’s disease might have altered emotional experiences is not known, but recent studies of patients with Alzheimer’s disease have suggested that even before symptoms become manifest, there is a neuronal deterioration in the anterior hippocampal/amygdala region, 20 , 21 and it has been well established that the amygdala is important for experiencing emotions, especially those with negative valence. 22 , 23 Fear conditioning (the method by which organisms learn to fear new stimuli), which appears to be dependent on amygdala functioning, has been found to be impaired in Alzheimer’s disease patients. 24 In addition, a recent functional neuroimaging study investigated the common areas of activations when healthy comparison subjects were exposed to facial expression of emotion and emotionally evocative scenes from the IAPS, 25 and both these sets of stimuli activate similar structures, including the amygdala.

Since the work of William James, there have been many theories of emotional experience which suggest that alterations of arousal are a critical element of emotional experience. 26 Studies of patients and animals have revealed that there are three cortical areas that appear to be involved in the “top down” or cortical control of arousal, including the inferior parietal lobes, the frontal lobes (dorsolateral and medial), and the cingulate gyrus. 4 The “bottom up” control of arousal is mediated by the ascending thalamic reticular system, including the intralaminar and parafascicular nuclei of the thalamus. The ascending neurotransmitter systems that appear to be important in bottom-up cortical activation include the cholinergic system that projects from the basal forebrain’s nucleus of Meynert to the cerebral cortex and the norepinephrine system which projects from the locus coeruleus to the cerebral cortex.

With Alzheimer’s disease there is often degeneration of the nucleus of Meynert-cholinergic and the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine systems. In addition, there is also degeneration of the parietal-frontal-anterior cingulate network that helps to modulate arousal systems. Marshall et al. 27 demonstrated that on post mortem examination the subjects who appeared to be apathetic when assessed by the NPI prior to death had degeneration of the anterior cingulate gyrus. Thus, perhaps in our subjects with Alzheimer’s disease, it was degeneration of these portions of the arousal network that accounted for their reduced valence ratings. Although there have been several studies of patients with Alzheimer’s disease that have demonstrated reduced phasic alerting or phasic arousal, 28 , 29 we are not aware of an investigation on arousal responsiveness to emotional pictures in Alzheimer’s disease, and future research might want to more directly test this arousal hypothesis.

Van Stegeren et al. 30 recently published an fMRI study investigating the effect of propanolol (which blocks the noradrenergic activation in the brain) or placebo on the amygdala’s activation while healthy subjects were watching neutral or highly negative pictures. Their results indicated that the propanolol selectively decreased the amygdala’s activation for the emotional pictures, providing support for the postulate that the neurotransmitter norepinephrine modulates the activity of the amygdala when processing emotional stimuli. Based on these results, we might speculate that the degeneration of the norepinephrine system in patients with Alzheimer’s disease might have an impact on the amygdala’s activation resulting in a lower arousal and a reduced valence rating of the presented emotional pictures. Future research will have to be performed to elucidate the mechanisms for the abnormal behaviors we observed.

1. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Service Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–944Google Scholar

2. Oppenheim G: The earliest sign of Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 37:511–514Google Scholar

3. Patterson MB, Mack JL, Mackell JA, et al: A longitudinal study of behavioral pathology across five levels of dementia severity in Alzheimer’s disease: the Cerad Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997; 11(suppl 2):S40–S44Google Scholar

4. Heilman KM, Valenstein E: Emotional disorders associated with neurological disease, in Clinical Neuropsychology. Edited by Heilman KM, Valenstein E. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003, pp 447–478Google Scholar

5. Levy ML, Cummings LA, Fairbanks D, et al: Apathy is not depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:314–319Google Scholar

6. Marshall GA, Monserratt L, Harwood D, et al: Positron emission tomography metabolic correlates of apathy in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2007; 64:1015–1020Google Scholar

7. Marin RS: Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:243–254Google Scholar

8. Cummings JL: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology 1997; 48:S10–16Google Scholar

9. Testa JA, Beatty WW, Gleason AC, et al: Impaired affective prosody in AD: relationship to aphasic deficits and emotional behaviors. Neurology 2001; 57:1474–1481Google Scholar

10. Brosgole L, Kuruez J, Plahovinsak TJ, et al: On the mechanism underlying facial-affective agnosia in senile demented patients. Int J Neurosci 1981; 15:207–215Google Scholar

11. Allender J, Kaszniak AW: Processing of emotional cues in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Int J Neurosci 1989; 46:147–155Google Scholar

12. Lang JP, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN: The International Affective Picture System [photographic slides]. Gainesville, Fla: The Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida, 2001Google Scholar

13. Grühn D, Scheibe S: Age-related differences in valence and arousal ratings of pictures from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS): do ratings become more extreme with age? Behav Res Methods 2008; 40:512–521Google Scholar

14. Dunn BD, Dalgleish T, Lawrence AD, et al: Categorical and dimensional reports of experienced affect to emotion inducing pictures in depression. J Abnorm Psychol 2004; 113:654–660Google Scholar

15. Sloan DM, Strauss ME, Quirk SW, et al: Subjective and expressive emotional responses in depression. J Affect Disord 1997; 46:135–141Google Scholar

16. Sloan DM, Strauss ME, Wisner KL: Diminished response to pleasant stimuli by depressed women. J Abnorm Psychol 2001; 110:488–493Google Scholar

17. Blonder LX, Bowers D, Heilman KM: The role of the right hemisphere in emotional communication. Brain 1991; 114:1115–1127Google Scholar

18. Bradley MM, Sabatinelli D, Lang PJ, et al: Activation of the visual cortex in motivated attention. Behav Neurosci 2003; 117:369–380Google Scholar

19. Albert MS, Cohen C, Koff E: Perception of affect in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol 1991; 48:791–795Google Scholar

20. Lehtovirta M, Laakso MP, Frisoni GB, et al: How does the apolipoprotein E genotype modulate the brain in aging and in Alzheimer’s disease? A review of neuroimaging studies. Neurobiol Aging 2000; 21:293–300Google Scholar

21. Reiman EM, Caselli RJ, Chen K, et al: Declining brain activity in cognitively normal apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 heterozygotes: a foundation for using positron emission tomography to efficiently test treatments to prevent Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98:3334–3339Google Scholar

22. Stark R, Schienle A, Walter B, et al: Hemodynamic responses to fear and disgust-inducing pictures: an fMRI study. Int J Psychophysiol 2003; 50:225–234Google Scholar

23. Stark R, Schienle A, Walter B, et al: Hemodinamic effects of negative emotional pictures: a test–retest analysis. Neuropsychobiology 2004; 50:108–118Google Scholar

24. Hamann S, Monarch ES, Goldstein FC: Impaired fear conditioning in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia 2002; 40:1187–1195Google Scholar

25. Britton JC, Taylor SF, Sudheimer KD, et al: Facial expression and complex IAPS pictures: common and differential networks. Neuroimage 2006; 31:906–919Google Scholar

26. LeDoux JE: Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 2000; 23:155–184Google Scholar

27. Marshall GA, Fairbanks LA, Tekin S, et al: Neuropathologic correlates of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2006; 21:144–147Google Scholar

28. Tales A, Snowden RJ, Brown M, et al: Alerting and orienting in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology 2006; 20:752–756Google Scholar

29. Festa EK, Ott BR, Heindel WC: Considering phasing alerting in Alzheimer’s disease: comment on Tales et al. (2006). Neuropsychology 2006; 20:757–760Google Scholar

30. Van Stegeren AH, Goekoop R, Everaerd W, et al: Noradrenaline mediates amygdale activation in men and women during encoding of emotional material. Neuroimage 2005; 24:898–909Google Scholar