Neuropathic Pain Syndrome Displayed by Malingerers

DSM-IV-TR 9 defines malingering in the section “Additional conditions that may be a focus of clinical attention” as “the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms, motivated by external incentives such as avoiding military duty, avoiding work, obtaining financial compensation, evading criminal prosecution, or obtaining drugs.” Halligan et al. 10 powerfully brought together medical, neuropsychological, legal, and social perspectives on the subject. The suspicion of malingering naturally crosses the minds of clinicians facing patients with atypical complaints of various kinds in the absence of demonstrable medical bases. Prevalence of malingering for chronic pain was assessed as 31% in the robust study by Mittenberg et al. 11 Among 50 patients with compensation claims for musculoskeletal pain treated in a pain clinic, Kay and Morris-Jones 12 found 20% to be proven malingerers, as shown by covert video surveillance. However, malingering is seldom reported formally in the literature on patients displaying chronic neuropathic pain, and there are no available statistics on malingered neuropathic pain.

Here we report 16 individuals communicating intractable chronic pain associated with psychophysical positive and negative motor and sensory displays, in absence of objective clinical or physiological equivalents of neuropathology, who were proven to be malingerers by surveillance. 13

METHODS

This series emanated from a population of 237 patients referred to the Oregon Nerve Center between January 2000 and July 2007 for chronic, seemingly neuropathic, pain. After informed consent, the subjects entered a standard clinical protocol described earlier. 14 , 15 This was followed by nerve conduction measurements and electromyography for physiological evaluation of large caliber afferent and motor fibers; somatosensory evoked potentials and transcranial magnetic motor stimulation for evaluation of central pathways; quantitative somatosensory thermotest to assess function of small caliber afferent pathways; infrared telethermography to evaluate function of sympathetic vasomotor activity and antidromic vasodilatation; and placebo-controlled (inert and active) somatic and sympathetic blocks.

Participants entered this series if surveillance evidence of malingering became available to us. The video recordings were obtained in public places by professional agents appointed independently by the patient’s third party agencies; we did not ourselves institute surveillance. Typically, surveillance had been implemented opportunistically for patients with medically unexplainable chronic symptoms and gross inconsistencies upon repeated medical evaluations. Traditional but nonspecific psychological tests intended to detect deception were not implemented. 16 Two patients who underwent surveillance by naked eye were shown to function normally in public places on the day of a medical evaluation during which they displayed much illness behavior. Criteria for diagnosis of malingering were misrepresentation of pain, hyperalgesia, or sensory loss as reasons for functional disability and misrepresentation of weakness, paralysis, or abnormal movements, all of which were assessed as medically incompatible with surveillance evidence of intact, able-bodied, sensory, and motor performance. Only those patients displaying gross inconsistency between the volunteered complaints and the surveillance evidence were included.

RESULTS

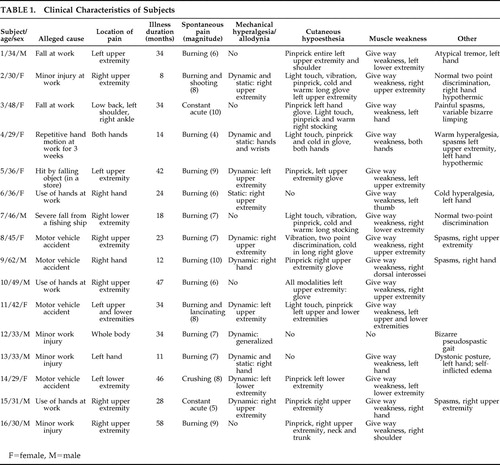

We analyzed sixteen positive video recorded cases. Fourteen indicated malingering, and two records showed inconsistencies between the verbal and behavioral display in the clinic, versus the surveilled behaviors, but these were not regarded as gross enough. Therefore this series includes 14 video recorded subjects plus two monitored visually. The 16 malingerers constitute a small percentage (5.9%) of the overall population of “neuropathic pain” patients seen in our center. However, only a small proportion of the 237 patients were tested for malingering by initiative of the disability insurers. There were eight women and eight men, ages 29 to 62 (average 38.3 years old) ( Table 1 ). Four subjects complained of persistent pain and disability attributed to repetitive limb motion at work; six had suffered a minor work injury and one a major injury; four injuries followed a motor vehicle accident; and one patient had a trivial injury in a store. The time from injury to evaluation ranged from 8 to 58 months (average 28.1 months).

|

Seven subjects complained of pain in the right and four in the left upper extremity; one in both uppers; one in the left-sided extremities; one in the left lower extremity; one in the low back, left shoulder, and right ankle; and one communicated whole body pain after minor left ankle trauma. Subjective pain magnitude ranged 4–10 in a 10-point scale (average 7.3). Without exception every subject volunteered ongoing worsening of symptoms and displayed much pain behavior to physicians. Eleven were known to be on long-term narcotics by medical prescription. All were in litigation for alleged disability postinjury.

On neurological examination, nonanatomical and variable areas of cutaneous hypoesthesia to light touch, pinprick, and cold and warm sensation were found in odd combinations in 12 subjects; 11 displayed nonanatomical cutaneous mechanical hyperalgesia, of dynamic type in 10 and static type in three 17 ; 15 had give way weakness and eight displayed fixed dystonia or atypical abnormal movements. Tendon reflexes were regularly normal.

Telethermography showed a hypothermic extremity in four cases, as has been described after disuse. 18 All had available sympathetic vasomotor reflex responses. Nerve conduction studies, electromyography, somatosensory evoked potentials, and transcranial motor stimulation were always normal. Quantitative somatosensory thermotest disclosed subjective cold hyperalgesia in three and associated heat hyperalgesia in one. One subject reported erratic thermal thresholds; four reported warm and cold hypoesthesia in the affected extremity. Four patients expressed subjective pain relief in response to inert placebo injection prior to diagnostic block, two of them featuring additional telltale recovery of deficits: weakness and sensory loss.

Several neurological findings signified pseudoneurological dysfunction without organic substrate, namely give-way weakness of commanded maximal voluntary muscle contraction, due to interrupted willful drive; bizarre abnormal movements; nonanatomical and fluctuating areas of cutaneous hypoesthesia or hyperalgesia/allodynia; and normalization of hypoesthesia, muscle weakness, or abnormal movements by inert or active placebo intervention. 14 , 15 , 19 – 26 However, these signs were not cardinal enough to discriminate “hysterical” conversion/somatization from malingering. This is where surveillance proves essential in differential diagnosis.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 34-year-old man injured his left arm at work. X-rays were normal. Thereafter, pain invaded the whole extremity, neck, and ear. He described swelling, numbness, hand tremor, and weakness. He was labeled with reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD)/CRPS I. He received nine stellate sympathetic ganglion blocks, which transiently relieved the self-reported pain. He eventually sued for personal injury. We evaluated him 34 months after injury. He volunteered severe pain in the entire left upper extremity. There was normal muscle bulk, tone and reflexes, and a distractible, irregular tremor of the left hand. He displayed give-way weakness behavior of the upper extremity. There was psychophysical hypoesthesia in the entire left upper extremity and posterior shoulder. Nerve conductions and needle EMG were normal. Transcranial motor stimulation and somatosensory evoked potentials were normal. Quantitative sensory thermotest was erratic. Telethermography showed symmetrical thermal emission profile of both hands, with normal sympathetic vasoconstrictor reactivity. A diagnostic placebo-controlled lidocaine block induced cutaneous anesthesia in median territory while abolishing the pain complaint in the upper extremity and normalizing the limb paresis. A placebo-controlled sympathetic block with intravenous phentolamine versus saline versus sympathomimetic phenylephrine again induced recovery of muscle strength (paradoxically following phenylephrine) but no pain relief. We diagnosed a pseudoneurological painful syndrome, possibly associated with a conversion/somatization disorder. A psychiatrist raised the possibility of malingering. Secret video surveillance, recorded on the dates of evaluation, caught the subject in the street and airport carrying a bag on either shoulder and using either upper extremity naturally for manipulation, without pain behavior, weakness, or abnormal movements.

Cases 2–4 are available online at http://neuro.pyschiatryonline.org.

DISCUSSION

Hysterical Conversion/Somatization, Malingering, and Surveillance

In conversion disorder, according to APA, 9 the “somatic symptom represents a symbolic resolution of an unconscious psychological conflict” (page 494), obtaining or not a secondary gain through symptoms that “are not intentionally produced to obtain the benefits.” In conversion/somatization disorders, pseudoneurological symptoms are typically present. 5 , 7 , 9

In contrast to hysterical conversion, malingering is a conscious feigning of illness and the purpose is overt. 27 It is a medical diagnosis but not a specific disease. Various clinical behaviors are particularly suspect of malingering, 9 , 28 but psychological methods to detect deception are still not powerful enough. 29 Jones 30 writes, “It may be almost impossible for a court to conclude that the claimant is malingering without wholly convincing evidence, such as video observation of the claimant over a period of time.” Therefore surveillance is indispensable to assess whether an illness behavior may be a lie 12 , 13 , 31 and constitutes a historical resource in the realm of chronic pain diagnosis. 32 Malingering is under-recognized because it requires opportunistic and covert documentation of behaviors that refute veracity of the alleged symptoms. 33 Pain management physicians never recommend surveillance of pseudoneurological patients they label with CRPS I, and therefore only a minority of our CRPS I patients had been surveilled. When surveillance is incompatible with the reported or enacted disability, malingering is practically definite. False positives are inconceivable in nonmalingerers. Therefore the positive predictive power of surveillance must be very high, 34 but the method is bound to substantial false negatives by chance, or because the subject may be aware of surveillance.

Here we document that, among many other possible choices, malingerers may enact a fraudulent and fairly stereotyped clinical profile of immeasurable pain associated with elements from the limited natural inventory for illness expression in a limb, namely displayed weakness, abnormal movements, sensory loss, allodynia, hyperalgesia, and changes in the physical appearance of the segment. We emphasize that such clinical display amounts to subjective self-report or is susceptible to willful modulation or self-infliction. The objective physical changes can result just from disuse rather than from autonomic neuropathology. 18 This profile is often assessed concretely by the clinician as implying “neuropathic pain.”

Neuropathic Pain and CRPS I: Taxonomy and Hypothetical Mechanisms

“Neuropathic pain” is a debated clinical attribution reserved by some authors to characterize patients with structural (“tissue”) neuropathology, 2 and broadened by others to encompass patients exhibiting atypical neurological dysfunction without demonstrable neuropathophysiology, but with assumed peripheral or central hyperexcitability. 35 , 36 Whereas it is no surprise that such a malleable profile may be simulated by malingerers, we remark that those who thus malinger invariably end up labeled as CRPS I because they do not carry a neuropathological lesion to qualify for CRPS II and, we argue, because the descriptive category CRPS I flexibly accommodates atypical “neuropathic” clinical profiles without testable physical bases. Refreshingly, the new redefinition implicitly excludes CRPS I from “neuropathic pain.” 3

As a diagnostic concept, CRPS I is also debated. It is taken to reflect neurological dysfunction; its localization and pathology are “unknown,” and there is no diagnostic test. The task force on taxonomy of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) chose the following diagnostic criteria for CRPS I:

1. The presence of an initiating noxious event, or a cause for immobilization; 2. Continuing pain, allodynia, or hyperalgesia with which (sic) the pain is disproportionate to any inciting event; 3. Evidence at some time of edema, changes in skin blood flow, or abnormal sudomotor activity in the region of the pain.

Criterion 4, one that “must be satisfied,” reads: “This diagnosis is excluded by the existence of conditions that would otherwise account for the degree of pain and dysfunction.” 1 Thus, the label “CRPS I” is by default; a leftover nickname that lacks evidential medical power. It is assumed to be a syndrome, or even a discrete disease, when in fact it is a listing of nonspecific symptoms and signs awaiting differential diagnosis, which is traditionally bypassed. 37 – 39 Neurophysiological testing is wrongly dismissed as futile because it is predictably normal, even in the presence of displayed weakness, paralysis or sensory loss. In absence of differential diagnostic workup for these patients, management is abortive and only iatrogenic harm can follow. 37 , 40 , 41

Hypothetical neuropathophysiological mechanisms are also controversial for CRPS I. For Max, 2 in CRPS I there is no neural lesion and the evidence of neurological dysfunction is precarious as it relies on self-reported allodynia, pain, and abnormal motion, unaccompanied by true clinical and physiological signs of functional impairment. Conversely, Merskey 36 argues that the clinical resemblance of CRPS I and CRPS II implies that both profiles are “neuropathic” and states that CRPS I reflects “a dysfunctional set of neurons.” In reality, the resemblance is shallow. CRPS I patients express atypical neurologically unexplainable symptoms, and there is no measurable biological evidence of neuronal dysfunction. 4 Humans and experimental animals with documented nerve pathology do not display these atypical clinical profiles. 4 , 42 All there is for putative neural mechanisms behind CRPS I is an unverifiable claim of sensitization of second order neurons by nociceptor barrage, assumed by uncritical extrapolation to explain perpetuation and expansion of pseudoneurological symptoms. 43 , 44

The sympathetically maintained pain hypothesis can be dismissed on the grounds of negative current scientific medical evidence. 37 , 45 In turn, the hypothesis that these patients harbor subclinical neuropathology of peripheral unmyelinated fibers is not supportable by reliable data. Indeed, evidence-based differential diagnosis was not implemented for the eight chronic pain patients labeled CRPS I (RSD) and studied histopathologically by van der Laan et al. 46 Several of them displayed atypical dystonia. The nerve and muscle samples were obtained from amputated legs with severe recurrent infections or chronic edema, and the authors concluded that there was “no consistent pathology in the peripheral nerves.” A reduced myelinated fiber density was partly attributed by the authors to endoneurial edema. The changes in unmyelinated fibers reported in four of the eight cases (median age 40.5 years) are explainable by aging alone. 47 , 48 To their credit however, the Dutch authors correctly recognize that the concept of sympathetically maintained pain may be rejected as a placebo artifact and that the pathogenesis of RSD is unclear. Today, German authors argue against this peripheral hypothesis. 49 , 50

More than a few neurologists have regarded the clinical profile that many denominate RSD/CRPS I as potentially brain/mind driven. 20 , 51 , 52 Determination of psychogenic origin should not be based just upon absence of detectable physiological anomaly. It should be based upon demonstration of neurophysiological normality of self-reportedly disturbed, subjective sensory, or willfully drivable motor functions, but most importantly upon explicit detection of reputable pseudoneurological phenomena that are assessed as psychogenic by DSM-IV-TR and by learned authors. 5 – 7 In the case of many subjects labeled CRPS I, pseudoneurological phenomena include (a) fluctuating cutaneous hypoesthesia or hyperalgesia/allodynia, spreading or metastasizing beyond neural, radicular or segmental territories 4 , 20 , 24 ; (b) punctual verbal denial, while blindfolded, of every brief natural stimulus within a reportedly anesthetic area 15 , 53 , 54 ; (c) normal two-point discrimination of stimuli applied to areas of reportedly profound hypoesthesia; (d) hypoesthesia reversed by placebo 15 ; (e) muscle weakness with interrupted voluntary upper motor neuron drive, even in absence of inhibiting pain 14 , 19 , 23 ; (f) atypical abnormal movements or dystonia that are of sudden onset, distractible, entrainable, or relieved with placebo 21 , 22 , 25 , 26 ; and (g) recovery of paralysis with placebo. 25

The symptom allodynia deserves special analysis in this context. The mechanical hyperalgesia prevailing in the present cohort of subjects was of dynamic type ( Table 1 ) and is known to be mediated by myelinated fibers, 17 which places such abnormal sensation in the category of allodynia , a term coined to specify a pain induced by stimuli that do not normally elicit pain. 1 For Lindblom and Hansson 55 allodynia mediated by tactile myelinated fibers reflected CNS dysfunction, specifically sensitization of second order neurons within the spinal cord, a hypothesis still dominant among pain researchers. 43 , 44 , 56 It is often ignored that allodynia might also be a clinical manifestation of hysteria, as pointed out by Mitchell, 57 or may be malingered as described by Jones and Llewellyn, 32 and clearly shown in the present series of patients. We agree with Max 2 that, in and of itself, the symptom allodynia does not necessarily indicate structural lesions nor dysfunction of the nervous system.

CRPS I: Brain Component

A minority of patients provisionally labeled with CRPS I are shown to harbor unrecognized neuropathy. 58 Most “classic” CRPS I patients display what seems at first sight a neuropathologically based illness, but the profile is characteristically atypical and pseudoneurological as there is neither demonstrable peripheral nor central pathway pathology. 4 , 59 This clinical profile reflects brain origin. 5 , 7 , 9 , 54 Changes in the brain are increasingly recognized in CRPS II and CRPS I patients. 60 Indeed, functional imaging of the brain in patients with posttraumatic neuropathic, or postherpetic neuralgia, relative to healthy comparison subjects, shows decreased activity of the contralateral thalamus. 61 These are likely plastic changes evoked by abnormal afferent activity from injured primary sensory neurons. Using functional MRI in patients labeled CRPS I, Apkarian et al. 62 reported widespread prefrontal hyperactivity, increased anterior cingulate limbic activity and decreased activity of the contralateral thalamus. These changes might signal injury to primary sensory neurons in unrecognized neuropathy (thus, CRPS II). We believe that in CRPS I such changes are primary and are unlikely to reflect amplification of the nociceptor-induced “spinal cord changes that accompany chronic pain conditions.” 62 Effective placebo removes both symptoms and functional MRI anomalies. 62 In hysterical conversion with sensory loss, striatothalamocortical neuronal circuits with important limbic input, believed to modulate sensory decoding, are pathologically deactivated. 63 Moreover, in hysterical patients communicating chronic pain and sensory loss, the areas of abnormal brain activity are the same as those reported in CRPS I 64 and signify neuronal activation of the emotional limbic brain. Abnormal brain imaging does not necessarily signify neuropathology. 65

CRPS I: Discrete Neurological Disease, Hysteria or Malingering?

All these malingerers fit IASP criteria for the label CRPS I. 1 It might be argued that by virtue of criterion 4, CRPS I is excluded because of the existence of a condition that accounts for the symptoms: malingering. Semantics aside, the undeniable existence of malingerers displaying what their physicians assessed as CRPS I proves that at least a subpopulation of CRPS I-labeled individuals are brain-driven cases of pseudoneurological illness behavior. Thus, it becomes mandatory to include both malingering and hysteria in the differential diagnosis of patients who fit the CRPS I menu because “the current IASP criteria for CRPS have inadequate specificity and are likely to lead to over diagnosis.” 66

Shaw 67 reckoned malingering to be the cause of RSD, although he failed to distinguish feigning from unconscious hysterical somatization. Conversely, rejecting the potential deliberate psychogenic nature of CRPS I/RSD is equally biased and challenged by previous reports 4 , 13 , 28 , 68 – 70 and by the present series of malingerers. Recently Mailis-Gagnon et al. 71 reported patients displaying the nonspecific profile of CRPS I, plus self-inflicted cutaneous stigmata, implying a gross personality disorder. Intriguingly, the authors acknowledge the patient’s factitious nature while stressing “the legitimacy of CRPS as a diagnosis.” The possibility that all CRPS I patients are malingerers is untenable given that many conversion/somatization-based unintentional pseudoneurological patients are truthful in the expression of their display. 72 On the other hand, malingerers might choose to amplify symptoms of a neuropathologically based condition legitimately, causing spontaneous pain and associated sensory and motor manifestations, but in the present series all subjects displayed CRPS I with only neurologically unexplained symptoms. 40 , 72 Besides, as per surveillance, we only included pure malingerers73 who feigned the entire symptom complex rather than just exaggerating bona fide symptoms. 74 Moreover, malingerers may amplify an unconscious, psychogenic, pseudoneuropathic painful syndrome since malingering is often concomitant with conversion/somatization. 75 , 76 This satisfies the concept that conversion/somatization involves self-deception while malingering is deception of others. 77 Using functional MRI, Spence et al. 78 observed that in healthy people who intentionally deceive there is activation of the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, which for Spence et al. 78 may be engaged in generating lies or withholding the truth. It is striking that cortical areas activated in conversion/somatization 79 are similar to areas activated in conscious deception. Thus, coexistence of conversion/somatization and feigned symptoms is in keeping with neuronal data.

We conclude that “neuropathic pain patients” classified in the provisional CRPS I category, who in reality may harbor an undiagnosed nerve injury (CRPS II) or unconscious hysterical conversion, alternatively or concomitantly may very well be malingerers. Unconscious conversion/somatization is a legitimate health disorder with no room for pejoratives. However, mistaking pseudoneurological displays, of one kind or another, for neuropathologically based disease fosters iatrogenesis by commission and by omission 51 , 80 – 83 and rewards those who feign. We have all missed more than one malingerer in our clinics. 5 , 84 , 85

1. Merskey H, Bogduk N: Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. IASP Task Force on Taxonomy, 2nd ed. Seattle, IASP Press, 1994Google Scholar

2. Max MB: Clarifying the definition of neuropathic pain. Pain 2002; 96:406–409Google Scholar

3. Treede R-D, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, et al: Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology 2008; 70:1630–1635Google Scholar

4. Verdugo RJ, Bell LA, Campero M, et al: Spectrum of cutaneous hyperalgesias/allodynias in neuropathic pain patients. Acta Neurol Scand 2004; 110:368–376Google Scholar

5. Shorter E: The borderland between neurology and history: conversion reactions. Neurol Clin 1995; 13:229–239Google Scholar

6. Shaibani A, Sabbagh MN: Pseudoneurologic syndromes: recognition and diagnosis. Am Fam Physician 1998; 57:2485–2494Google Scholar

7. Krem MM: Motor conversion disorders reviewed from a neuropsychiatric perspective. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:783–790Google Scholar

8. Ron M: Explaining the unexplained: understanding hysteria. Brain 2001; 124:1065–1066Google Scholar

9. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

10. Halligan PW, Bass C, Oakley DA: Willful deception as illness behavior, in Malingering and Illness Deception. Edited by Halligan PW, Bass C, Oakley DA: Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 2003, pp 3–28Google Scholar

11. Mittenberg W, Patton C, Canyock EM, et al: Base rates of malingering and symptom exaggeration. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2002; 24:1094–1102Google Scholar

12. Kay NRM, Morris-Jones H: Pain clinic management of medico-legal litigants. Injury 1998; 29:305–308Google Scholar

13. Kurlan R, Brin MF, Fahn S: Movement disorder in reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a case proven to be psychogenic by surveillance video monitoring. Mov Disord 1997; 12:243–245Google Scholar

14. Verdugo RJ, Ochoa JL: Use and misuse of conventional electrodiagnosis, quantitative sensory testing, thermography, and nerve blocks in the evaluation of painful neuropathic syndromes. Muscle Nerve 1993; 16:1056–1062Google Scholar

15. Verdugo RJ, Ochoa JL: Reversal of hypoaesthesia by nerve block, or placebo: a psychologically mediated sign in chronic pseudoneuropathic pain patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 65:196–203Google Scholar

16. Faust D: The detection of deception. Neurol Clin 1995; 13:255–265Google Scholar

17. Ochoa JL, Yarnitsky D: Mechanical hyperalgesias in neuropathic pain patients: dynamic and static subtypes. Ann Neurol 1993; 33:465–472Google Scholar

18. Butler SH: Disuse and CRPS, in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Progress in Pain Research and Management, vol 22. Edited by Harden RN, Baron R, Jänig W. Seattle, IASP Press, 2001, pp 143–150Google Scholar

19. Lambert EH: Electromyography and electrical stimulation of peripheral nerves and muscles, in Clinical Examination in Neurology. Edited by May Clinic staff eds. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1956Google Scholar

20. Walters A: Psychogenic regional pain alias hysterical pain. Brain 1961; 84:1–18Google Scholar

21. Fahn S, Williams DT: Psychogenic dystonia. Adv Neurol 1988; 50:431–455Google Scholar

22. Lang AE: Psychogenic dystonia: a review of 18 cases. Can J Neurol Sci 1995; 22:136–143Google Scholar

23. Wilbourn AJ: The electrodiagnostic examination with hysteria-conversion reaction and malingering. Neurol Clin 1995; 13:385–404Google Scholar

24. Trimble MR: Behavior and personality disturbances, in Neurology in Clinical Practice, 3rd ed. Edited by Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, et al. Newton, Mass, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000, pp 89–104Google Scholar

25. Verdugo RJ, Ochoa JL: Abnormal movements in complex regional pain syndrome: assessment of their nature. Muscle Nerve 2000; 23:198–205Google Scholar

26. Schrag A, Trimble M, Quinn N, et al: The syndrome of fixed dystonia: an evaluation of 103 patients. Brain 2004; 127:2360–2372Google Scholar

27. Turner M: Malingering, hysteria, and the factitious disorders. Cogn Neuropsychol 1999; 4:193–201Google Scholar

28. Mendelson G, Mendelson D: Malingering pain in the medicolegal context. Clin J Pain 2004; 20:423–432Google Scholar

29. Bogduk N: Diagnostic blocks: a truth serum for malingering. Clin J Pain 2004; 20:409–414Google Scholar

30. Jones MA: Lies and videotape: malingering as a legal phenomenon, in Malingering and Illness Deception. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 2003, pp 209–219Google Scholar

31. Kizorek B: Disability or deception: surveillance tapes helping doctors to decide. J Disability 1990; 1:119–125Google Scholar

32. Jones AB, Llewellyn LJ: Malingering or Simulation of Disease. Philadelphia, Blakiston’s Son & Co, 1917Google Scholar

33. Rogers R: An introduction to response styles, in Clinical Assessment of Malingering and Deception. Edited by Rogers R. New York, Guilford, 2008, pp 3–13Google Scholar

34. Hennekens CH, Buring JE: Epidemiology in Medicine. Boston, Little Brown, 1987Google Scholar

35. Jensen TS, Sindrup SH, Bach FW: Test the classification of pain: reply to Mitchell Max (letter). Pain 2002; 96:407–408Google Scholar

36. Merskey H: Clarifying definition of neuropathic pain. Pain 2002; 96:408–409Google Scholar

37. Ochoa J, Verdugo RJ: Mechanisms of neuropathic pain: nerve, brain, and psyche: perhaps the dorsal horn but not the sympathetic system. Clin Auton Res 2001; 11:335–339Google Scholar

38. Ochoa JL: Quantifying sensation: “look back in allodynia.” Eur J Pain 2003; 7:369–374Google Scholar

39. Loeser JD: Introduction, in CRPS: Current Diagnosis and Therapy. Progress in Brain Research and Management, vol 32. Edited by Wilson PR, Stanton-Hicks M, Harden RN. Seattle, IASP Press, 2005, pp 3–7Google Scholar

40. Schrag A, Brown RJ, Trimble MR: Reliability of self-reported diagnoses in patients with neurologically unexplained symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75:608–611Google Scholar

41. Rondinelli RD: Complex regional pain syndrome impairment, in Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 6th ed. Edited by Rondinelli RD, Andersson G, Dobie R, et al. Chicago, American Medical Association, 2008, pp 450–451Google Scholar

42. Ochoa JL: The irritable human nociceptor under microneurography: from skin to brain. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol 2004; 57:15–23Google Scholar

43. Woolf CJ, Mannion RJ: Neuropathic pain: aetiology, symptoms, mechanisms, and management. Lancet 1999; 353:1959–1964Google Scholar

44. Jensen TS, Gottrup H, Sindrup SH, et al: The clinical picture of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol 2001; 429:1–11Google Scholar

45. Ochoa JL: Truths, errors, and lies around “reflex sympathetic dystrophy” and “complex regional pain syndrome.” J Neurol 1999; 246:875–879Google Scholar

46. van der Laan L, Ter Laak HJ, Gabreëls-Festen A, et al: Complex regional pain syndrome type I (RSD): pathology of skeletal muscle and peripheral nerve. Neurology 1998; 51:20–25Google Scholar

47. Ochoa J: The Structure of Developing and Adult Sural Nerve in Man and the Changes Which Occur in Some Diseases: A Light and Electron Microscopic Study (PhD dissertation). University of London, 1970, p 202Google Scholar

48. Ochoa J: Recognition of unmyelinated fiber disease: morphologic criteria. Muscle Nerve 1978; 1:375–387Google Scholar

49. Jänig W, Baron R: Is CRPS a neuropathic syndrome? Pain 2006; 120:227–229Google Scholar

50. Ochoa JL: Is CRPS I a neuropathic pain syndrome? Pain 2006; 123:334–335Google Scholar

51. Ochoa JL, Verdugo RJ: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a common clinical avenue for somatoform expression. Neurol Clin 1995; 13:351–363Google Scholar

52. Landau WM: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (letter). Mayo Clin Proc 1996; 71:524–525Google Scholar

53. Collie J: Malingering and Feigned Sickness. London, Edward Arnold, 1913Google Scholar

54. Lanska DJ: Functional weakness and sensory loss. Semin Neurol 2006; 26:297–309Google Scholar

55. Lindblom U, Hansson P: Sensory dysfunction and pain after clinical nerve injury studied by means of graded mechanical and thermal stimulation, in Lesions of Primary Afferent Fibers as a Tool for the Study of Clinical Pain. Edited by Besson JM, Guilbaud G. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1991, pp 1–18Google Scholar

56. Jänig W, Baron R: Complex regional pain syndrome: mystery explained? Lancet Neurol 2003; 2:687–697Google Scholar

57. Mitchell SW: Injuries of Nerves and Their Consequences, 1872. New York, Dover Publications, American Academy of Neurology Reprint Series, 1965Google Scholar

58. Ochoa JL: Pathophysiology of chronic “neuropathic pains,” in Surgical Management of Pain. Edited by Burchiel KJ. New York, Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers, 2002, pp 25–41Google Scholar

59. Lacerenza M, Triplett B, Ochoa JL: Centralization in RSD/causalgia patients is not supported by clinical neurophysiological tests (abstract). Neurology 1996; 46:A161Google Scholar

60. Jänig W: CRPS-I and CRPS-II: a strategic view, in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Progress in Pain Research and Management, vol 22. Edited by Harden RN, Baron R, Jänig W. Seattle, IASP Press, 2001, pp 3–15Google Scholar

61. Iadarola MJ, Max MB, Berman KF, et al: Unilateral decrease in thalamic activity observed with positron emission tomography in patients with chronic neuropathic pain. Pain 1995; 63:55–64Google Scholar

62. Apkarian AV, Grachev ID, Krauss BR, et al: Imaging brain pathophysiology of chronic CRPS pain, in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Progress in Pain Research and Management, vol 22. Edited by Harden RN, Baron R, Jänig W. Seattle, IASP Press, 2001, pp 209–225Google Scholar

63. Vuilleumier P, Chicherio C, Assal F, et al: Functional neuroanatomical correlates of hysterical sensorimotor loss. Brain 2001; 124(part 6):1077–1090Google Scholar

64. Mailis-Gagnon A, Giannoylis I, Downar J, et al: Altered central somatosensory processing in chronic pain patients with “hysterical” anesthesia. Neurology 2003; 60:1501–1507Google Scholar

65. Grande LA, Loeser JD, Ozuna J, et al: Complex regional pain syndrome as a stress response. Pain 2004; 110:495–498Google Scholar

66. Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, et al: External validation of IASP diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome and proposed research diagnostic criteria. Pain 1999; 81:147–154Google Scholar

67. Shaw RS: Pathological malingering: the painful disabled extremity. N Engl J Med 1964; 271:22–26Google Scholar

68. Rodriguez-Moreno J, Ruiz-Martin JM, Mateo-Soria L, et al: Münchausen’s syndrome simulating reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Ann Rheum Dis 1990; 49:1010–1012Google Scholar

69. Chevalier X, Claudepierre P, Larget-Piet B, et al: Münchausen’s syndrome simulating reflex sympathetic dystrophy. J Rheumatol 1996; 23:1111–1112Google Scholar

70. Taskaynatan MA, Balaban B, Karlidere T, et al: Factitious disorders encountered in patients with the diagnosis of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Clin Rheumatol 2005; 24:521–526Google Scholar

71. Mailis-Gagnon A, Nicholson K, Blumberger D, et al: Characteristics and period prevalence of self-induced disorder in patients referred to a pain clinic with the diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome. Clin J Pain 2008; 24:176–185Google Scholar

72. Ron MA: Somatization in neurological practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57:1161–1164Google Scholar

73. Resnick PJ: The detection of malingered mental illness. Behav Sci Law 1984; 2:21–38Google Scholar

74. Main CJ: The nature of chronic pain: a clinical and legal change, in Malingering and Illness Deception. Edited by Halligan PW, Bass C, Oakley DA. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 2003, pp 171–183Google Scholar

75. Merskey H: The Analysis of Hysteria: Understanding Conversion and Dissociation, 2nd ed. Glasgow, UK, Bell & Bain Ltd, 1995Google Scholar

76. Weintraub MI: Chronic pain in litigation: what is the relationship? Neurol Clin 1995; 13:341–349Google Scholar

77. Spence SA: Hysterical paralyses as disorders of action. Cogn Neuropsychol 1999; 4:203–226Google Scholar

78. Spence SA, Farrow TFD, Herford AE, et al: Behavioral and functional anatomical correlates of deception in humans. Neuroreport 2001; 12:2849–2853Google Scholar

79. Marshall JC, Halligan PW, Fink GR, et al: The functional anatomy of a hysterical paralysis. Cognition 1997; 64:B1–B8Google Scholar

80. Kouyanou K, Pither CE, Rabe-Hesketh S, et al: A comparative study of iatrogenesis, medication abuse, and psychiatric morbidity in chronic pain patients with and without medically explained symptoms. Pain 1998; 76:417–426Google Scholar

81. Bell DS: Repetition strain injury: an iatrogenic epidemic of simulated injury. Med J Austr 1989; 151:280–284Google Scholar

82. Ochoa J: Neuropathic pain and iatrogenesis. Continuum Am Acad Neurol 2001; 7:91–104Google Scholar

83. Butler SH: Primum non nocere: first do no harm. Pain 2005; 116:175–176Google Scholar

84. Ford CV: Dimensions of somatization and hypochondriasis. Neurol Clin 1995; 13:241–253Google Scholar

85. Ochoa J: Pseudoneuropathy: conversion versus malingering, in Painful Pain Patients. Seattle, American Academy of Neurology 61st Annual Meeting, Education Program Syllabus, 2009; 7A-001–28-38Google Scholar