Mania and Pachygyria

He had a previous history of secondary generalized tonic–clonic epilepsy, which began at 14 years of age and was controlled with sodium valproate, but because of his taking the drug irregularly, he had seizures occasionally. Also, he had been summoned to court for several legal problems. His developmental milestones were normal, and he did not have a history of neonatal jaundice or convulsion. Since adolescence, he had been intrusive in his increased involvement with others, leading to friction with family members and friends. His other abnormal behaviors since adolescence include unaccustomed profanity and tactless jocularity, and impulsive and aggressive behavior. History of substance abuse was negative.

On examination, he had good grooming and eye contact. His psychomotor and speech tone and volume were increased, and he was agitated and distractible. His mood was irritable, but with appropriate affect. He had persecutory delusions, ideas of reference, and intrusive thoughts about involvement with others, as well as flight of idea. No hallucinations were present. The Mini-Mental State Exam score was 26 (of 30). All other neurological examinations, as well as general physical examination, was unremarkable.

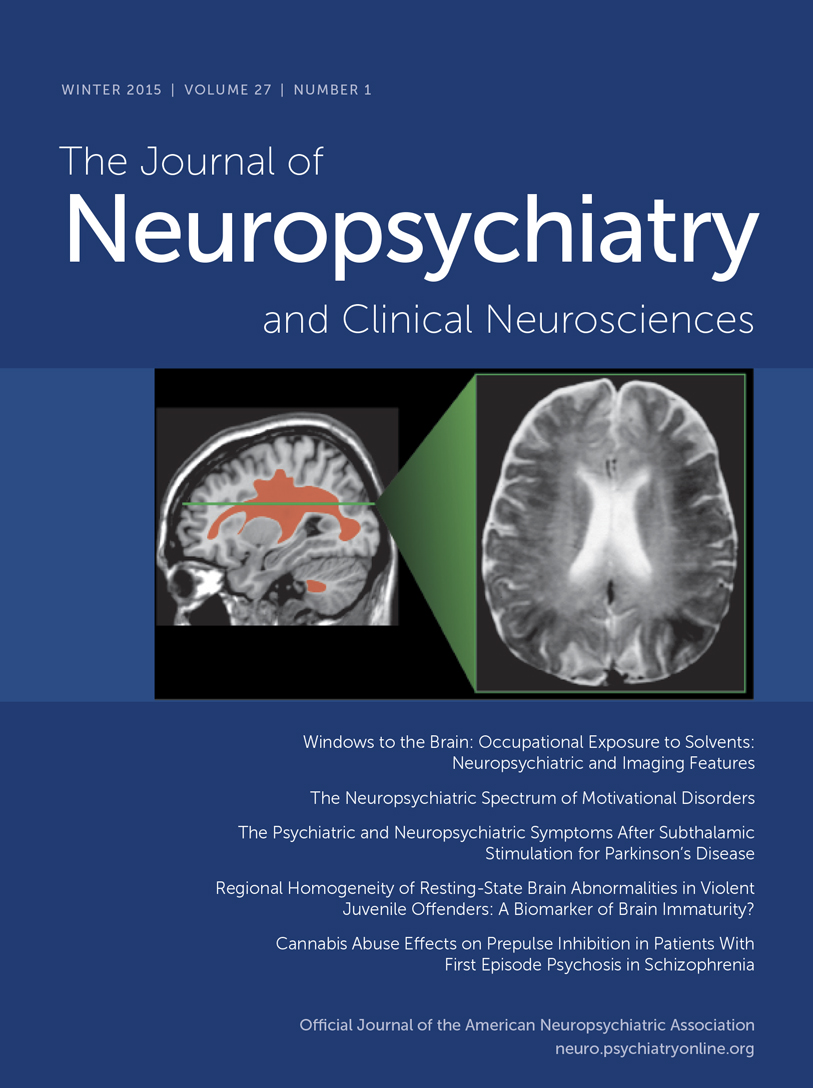

Routine laboratory examinations as well as urinary sample for opium, cannabis, and amphetamines were negative. His EEG did not show any abnormal discharges. In his MR imaging, bilateral increase in cortical diameter of temporal lobes (pachygyria) and fine gray matter foci in white matter of centrum semiovals in both frontal lobes were observed, which was suggestive of migrational anomaly (Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively).

The diagnosis of mania was established because of irritable mood, mood-congruent delusions, distractibility, pressure of speech, psychomotor agitation, and decreased need for sleep, as well as exclusion of other causes such as paranoid schizophrenia and substance abuse/withdrawal.

Sodium valproate (250 mg daily) was initiated and was titrated gradually to 1,250 mg in the 2nd week. The patient responded well to the medication, and this further supported the diagnosis of bipolar mood disorder (BMD). Also, we referred the patient to a psychotherapist for management of his impulsive behavior. The patient was discharged 7 days later.

Neuronal migration disorders including pachygyria and lissencephaly are a group of heterogeneous disorders characterized by mental retardation and epilepsy, and it is often accompanied by other malformations. In the recent years, several genes that regulate neuronal migration have been reported to be malfunctioning or show polymorphism in BMD. For example, DISC1 and Ndel1 are key regulators of neuronal migration and have been shown to be disrupted in BMD.1 In another study on a single nucleotide polymorphism, rs31745, related to protocadherin alpha gene-enhancer, a remarkable increase in homozygotes for the minor allele at this locus was shown in BMD.2 Protocadherins are important regulators of neuronal migration. Recent findings provided evidence between some lissencephaly-related genes and both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and influence on frontal executive function.3 Also, both epilepsy and BMD can be explained by abnormal kindling, which was shown to be disturbed in neuronal migration disorders.4,5

1. : The genetics and biology of disc1: an emerging role in psychosis and cognition. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 60:123–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. : Analysis of protocadherin alpha gene-deletion variant in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Psychiatr Genet 2008; 18:110–115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. : Evidence for association between structural variants in lissencephaly-related genes and executive deficits in schizophrenia or bipolar patients from a Spanish isolate population. Psychiatr Genet 2008; 18:313–317Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. : Bipolar disorder and epilepsy: a bidirectional relation? neurobiological underpinnings, current hypotheses, and future research directions. Neuroscientist 2007; 13:392–404Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. : Evidence of enhanced kindling and hippocampal neuronal injury in immature rats with neuronal migration disorders. Epilepsia 1998; 39:1253–1260Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar