Lateralization of Facial Emotional Expression in Schizophrenic and Depressed Patients

Abstract

This study examined facial emotional expressions produced by schizophrenic (SZ), unipolar depressed (UD), and normal control (NC) right-handed adults. Hypotheses regarding right-hemisphere activation in UD and suppression in SZ were addressed, as well as hypotheses about emotion and laterality. Subjects were videotaped while posing positive, neutral, and negative facial expressions to verbal command and to visual imitation. Naive judges rated hemiface stimuli for intensity in original and mirror-reversed orientations. Overall, SZs produced expressions with diminished intensity relative to UDs and NCs. Across subject groups, expressions were more intense in the visual than the verbal condition. In general, approach expressions were produced with greater right-hemiface intensity, and withdrawal expressions with greater left-hemiface intensity. UDs showed more pronounced facial asymmetry than SZs or NCs. An unanticipated right-hemispace perceptual bias among the judges may reflect the analytical, detailed rating procedure used and the presumably greater reliance by the judges on left- than right-hemisphere strategies.

The literature suggests that emotional expression is mediated by the right hemisphere.1–3 Consistent with findings that facial musculature is contralaterally innervated,4–6 studies of posed expression in normal right-handed adults have found asymmetries of expression. Specifically, emotionally laden or affective expressions are more intensely displayed on the left than the right side of the face.7,8 The notion of right hemisphere mediation of expression, referred to as the right-hemisphere hypothesis,9 can be contrasted with another theory on the generation of expression, known as the valence hypothesis.10 The latter hypothesis suggests that negative and positive emotions are differentially processed by the right and left hemispheres, respectively. A related version of this hypothesis (the motoric direction hypothesis), based on conceptual notions of Schnierla,11 suggests that approach emotions are mediated by the left hemisphere and withdrawal/avoidance emotions by the right hemisphere.12

If the production of facial emotional expression is more extensive or more intense on the side of the face corresponding to the contralateral hemisphere, then the behavioral manifestations of both the valence and motoric direction hypotheses would be that negative and withdrawal emotions are displayed more intensely on the left hemiface and that positive and approach emotions are displayed more intensely on the right hemiface. Alternatively, the right-hemisphere hypothesis implies that all emotional expressions will be more intensely displayed on the left than the right hemiface. One purpose of this study was to test the right-hemisphere, valence, and motoric direction hypotheses as applied to facial asymmetry during emotional expression.

Neurophysiological studies of lateralization in psychiatric populations13–15 have demonstrated right-hemisphere abnormalities in both unipolar depression and negative-symptom, flat-affect (type II) schizophrenia.16 Suppression of right-hemisphere anterior function has been suggested for individuals with type II schizophrenia (SZs).17 Cognitive and perceptual studies, which typically use emotionally neutral visuospatial or verbal stimuli,18–20 have suggested differential anterior/posterior right-hemispheric functioning for individuals with unipolar depression (UDs).21 For UDs, perceptual deficits suggest parietal dysfunction, whereas physiological measures indicate frontal activation greater than that of normal individuals.10 Since emotional expression is presumed to be mediated by anterior cortical structures,22 UDs might demonstrate increased right-hemisphere specialization in the display of emotion on tasks that typically show a right-hemisphere/left-hemiface advantage. However, because of suppressed right-hemispheric functioning, SZs might show decreased lateralization of facial emotion.

Because affective disturbance is a major component of most psychiatric disorders, it seems logical to also consider the lateralized processing of stimuli containing affective or emotional information.21,23–25 However, relatively few studies have investigated the extent to which decoding of affective stimuli or encoding of facial expression is lateralized in psychiatric populations. With respect to facial expression asymmetry, those studies that have been conducted in psychiatric patients26,27 have not considered a range of emotions or specific psychiatric diagnoses.

The main purpose of the current study was to examine facial asymmetry in UDs, SZs, and normal control subjects (NCs). Facial expressions were elicited to both verbal command and visual imitation and were rated in original and mirror-reversed orientations. Because verbal and visual instructions could selectively activate one hemisphere (verbal, left; visual, right), both elicitation conditions were included for control purposes. Orientation was controlled for in light of research suggesting a left-hemispace advantage for processing facial emotional stimuli.28,29

If the right-hemisphere hypothesis is operative, then the left hemiface would generally be rated as more expressive for all emotions posed. Because UDs and flat-affect SZs are presumed to have, respectively, elevated and diminished right-hemisphere functioning, the right-hemisphere hypothesis would predict greater facial asymmetry for UDs than for SZs. In contrast, the valence and directional hypotheses predict that UDs, SZs, and NCs will portray similar degrees of right-hemiface intensity for positive/approach emotions, whereas during the expression of negative/withdrawal emotions, left-hemiface involvement would be greater for UDs than for NCs and greater for NCs than for SZs.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were 16 schizophrenic, 11 unipolar depressed, and 18 normal control right-handed adults. Handedness was determined by self-report and confirmed by inventory.30 Psychiatric subjects were diagnosed according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC)31 via the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) diagnostic interview.32 NCs had no history of psychiatric disorder (SADS–Lifetime Version32). All subjects were screened for no history of neurological disease, dementia (via subtests from the Dementia Rating Scale33), mental retardation (via the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised Vocabulary subtest34), or substance abuse. Please note that these subjects were included in two previous expression studies, one examining spontaneous facial expression in SZs, NCs, and right brain–damaged subjects (RBDs),35 and one examining posed facial expression, using whole-face rather than hemiface measures, in SZs, UDs, and NCs, as well as RBDs and Parkinson's disease patients.36 Subjects provided informed consent to their participation in the study.

Schizophrenic subjects were referred for the study by a psychiatrist on the basis of 1) clinical impression of negative symptoms37 and flattened affect, and 2) RDC for chronic schizophrenia. All SZs exhibited symptoms of flat affect according to four rating scales: a mean score of 2.31 (possible range 0–5) on “Affective Flattening,” item 8 on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS);38 a mean score of 5.25 (possible range 0–11), sum of all the items on the Negative Symptom Scale;39 a mean score of 1.09 (possible range 0–2), sum of the four items on the Affect subscale of the Rating Scale for Emotional Blunting;40 and a mean score of 3.44 (possible range of 1–7) on “Blunted Affect,” item 16 on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.41

The SADS was administered by research assistants who had received training in clinical interviewing and had established interrater reliability using this instrument. The rating scales were completed by the examiner after 1) medical chart review; 2) a general interview to gather demographic, background, and medical information; 3) administration of the neuropsychological tests; and 4) the SADS interview. From these sources of information, subjects with histories of neurological disorder or substance abuse were excluded from the study.

Next, subject characteristics were examined. Demographic characteristics (age, gender, education, and occupation) and general cognitive ability are reported in Table 1 for each subject group. In terms of ethnicity, there were 7 white, 6 black, and 3 Hispanic SZs; 11 white UDs; and 16 white, 1 black, and 1 Hispanic NC. When one-way analyses of variance or chi-square tests were conducted, there was a significant effect of subject group for each of the six variables. Statistical controls were considered to account for these group differences (see Results).

Expression Elicitation

Subjects were videotaped while posing eight facial expressions: positive/pleasant: happiness, pleasant surprise, and interest/excitement; negative/unpleasant: sadness, fear, anger, and disgust; and neutral (indifference). Subjects were randomly assigned to one of two different expression elicitation orders. To ensure that future ratings would be based on a complete image of the face rather than on a partial facial profile, the subjects were instructed to look straight ahead and were seated in a chair with a headrest that encouraged an upright and forward-looking position.

Facial exercises were conducted to familiarize the subject with the expression production task and to facilitate the display of the best possible expression. During this practice phase, all parts of the face (mouth, eyes, cheeks, nose, and chin) were involved, and subjects were given feedback as to the flexibility of their facial movements. Additionally, this “warm-up” procedure43 focused the subjects' attention on the task to increase the likelihood that voluntary expressions (presumably cortically controlled) would be produced. After the practice phase, subjects were requested to pose each of the eight emotions two times in response to a verbal command, e.g., “Look happy. Ready, go!” These procedures for eliciting expressions were developed by Borod et al. for use with normal43,44 and clinical populations.45,46

For the visual imitation task, the posers were shown standardized pictures of emotional expressions.47 The command to produce an imitated expression was similar to that for purely verbal elicitation, e.g., “Now, look happy like this man/woman. Ready, go!”

Stimulus Preparation

After the initial videotaping, the subjects' poses were edited onto a set of rating tapes such that the 16 expressions (verbal and visual conditions) of one individual from each diagnostic category were randomly placed on an edited tape. The subjects on each tape were matched as closely as possible on demographic variables (e.g., age and education). The tapes were edited by two right-handed women who determined, by consensus, the tape frame displaying the peak of emotional intensity in each expression that followed the command “Ready, go!” To control for perceiver asymmetries, the poses for half of the subjects in each diagnostic group were rated in the original orientation, and for the other half, in the mirror-reversed orientation.

Expression Ratings: Raters

Four right-handed normal adults served as raters and were naive regarding the subject groups and the experimental hypotheses of the study. Raters were recruited by posted flyers and word of mouth at a large urban college. Raters were non-psychology undergraduate and graduate students who ranged in age from 25 to 31 (mean age=27.8 years). There were two white males, one black male, and one white female. The gender and ethnic breakdown of the raters (75% male, 75% white) approximated the breakdown for the 45 posers under study (69% male, 76% white). All raters were right-handed by self-report and as confirmed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory.48 Raters were screened, via a comprehensive medical history questionnaire,49 for no history of neurological disease, mental retardation, serious medical illness, psychiatric disorder, substance abuse, or psychotropic medication treatment.

Raters viewed hemiface presentations of each emotional expression and assessed each hemiface for expression intensity on a 7-point Likert scale. The hemiface stimuli (original and reversed orientation) were created by blocking one-half of the video monitor with a piece of black cardboard, which was secured to the monitor with Velcro strips. The vertical midline of the face was predetermined for each pose by identifying the center of the space between the poser's eyes, the center of the bridge and point of the nose, the philtrum, and the point of the chin. These four reference points were adapted from Sackeim et al.50 For ease of presentation, the videotapes were calibrated so that the experimenter could fast-forward to the exact location of each relevant pose.

Expression Ratings: Procedures

The procedures used for training raters and rating facial expressions were based on those used by Borod et al.44 and Moreno et al.51 They were designed to teach the concept of intensity in a fashion that would easily allow generalization from whole-face stimuli to hemifaces, and from photographs to the videotape medium. Because faces are normally viewed as whole units, the concept of muscular intensity was introduced at this level and then extended to hemiface stimuli.

First, an operational definition of intensity was introduced as the degree of facial muscle involvement in the production of an expression. Attention was directed to wrinkles in the face caused by tightening of the skin around the eyes and mouth, the depth of the nasolabial fold, and the drawing up of the cheeks and eyebrows. To illustrate “intensity,” the raters were shown examples of whole-face expressions52 that varied with respect to overall intensity. The sample faces were presented so as to demonstrate a continuum of intensity for several emotions (e.g., happiness and disgust). Examples of neutral expressions were also shown.

After the raters studied these examples, they were presented with 16 unlabeled expressions (2 each of the 8 expressions). The raters were instructed to independently rate these expressions for muscular intensity. Afterwards, their ratings were compared with those previously determined by consensus among three experienced investigators, and each of the 16 practice items was discussed by the group of raters. To make sure the raters understood the concept of intensity, they were each asked to write an operational definition of facial muscular intensity.

The next aspect of training involved the presentation of 28 hemiface “flash cards” for rating. This step extended the task to hemifaces using stimuli adapted from a study by Jaeger.49 The group viewed each flash card and rated the intensity until consensus was achieved.

Finally, the rating task was adapted to videotaped presentations. In this phase, the raters were shown two sets of 24 videotaped hemifaces (3 each of the 8 expressions) that were selected to demonstrate a broad range of emotions and intensity ratings. The raters worked independently as the experimenter presented each of these test stimuli in a manner similar to that which would be implemented in the actual experiment. Then, ratings were reviewed item by item, and any item with a 2-point or greater span of ratings was conferenced among the raters. Additionally, the raters were encouraged to use the entire 7-point range of values. After these procedures, interrater reliability was assessed on a subset of 24 videotaped hemifaces (3 each of the 8 expressions), and substantial reliability was obtained (Cronbach's alpha=0.94).

Possible trainer bias should have been minimized by the following features of our study: 1) we used a rigorous rating system; 2) we used a range of stimuli with faces of both normal individuals and psychiatric patients (none of which were identified to the raters); 3) we focused the raters' attention on objective variables—e.g., facial muscle involvement caused by skin tightening around the eyes and mouth, the depth of the nasolabial fold; 4) we had different people as the rater trainer and the subject examiner; and 5) we had the raters work independently to minimize the formulation and discussion of hypotheses regarding subject characteristics.

RESULTS

In order to test the hypotheses of this study, a mixed-design repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. There were two between-subjects factors: Diagnostic Group (SZ, UD, NC) and Orientation (Original, Reversed); and three within-subjects factors: Condition (Verbal, Visual), Expression (Happy, Pleasant Surprise, Interest/Excitement, Neutral, Sad, Angry, Fear, Disgust), and Hemiface (Right, Left). Significant main effects and interactions were tested with the Newman-Keuls post hoc procedure. In light of the subject group differences on demographic and cognitive variables (see Methods), the relationship between these subject variables and the experimental variables was examined by computing Spearman rank-order correlations for each subject group. Because only 8% of the resulting correlation coefficients were significant, subject characteristics were not controlled for in the analyses to follow.

Subject Group

Overall, there was a significant main effect of Group (F=7.78, df=2,78, P≤0.001). By use of post hoc tests, the facial expressions of SZs (mean=3.11) were rated as significantly less intense than those of UDs (mean=3.68) or NCs (mean=3.69). This effect was modified by a significant interaction between Group and Expression (F=3.42, df=14,546, P<0.001). In general, the expressions of the SZs were produced less intensely than were those of the other two groups (Table 2). On post hoc tests, comparisons between SZs and NCs were significant for Happiness, Pleasant Surprise, Interest/Excitement, Anger, and Disgust; comparisons between SZs and UDs were significant for Happiness, Pleasant Surprise, Sadness, Anger, and Disgust. For UDs and NCs, in general, UDs expressed negative and neutral expressions more intensely than NCs, and NCs expressed positive expressions more intensely than UDs. When post hoc tests were conducted, only the group comparisons (UDs vs. NCs) for Sadness and Happiness were significant.

Elicitation Condition

There was a significant main effect of Condition (F=8.84, df=1,78, P<0.005). Overall, expressions posed to visual imitation (mean=3.73) were rated as more intense than those posed to verbal command (mean=3.26). This finding was modified by a significant interaction between Condition and Expression (F=6.33, df=7,546, P<0.001). All expressions, except for Neutral, were produced more intensely in the visual than the verbal condition (Table 3). When post hoc tests were conducted, condition differences (visual vs. verbal) were significant for Happiness, Pleasant Surprise, Fear, Anger, and Disgust.

Expression

There was also a significant main effect for Expression (F=55.87, df=7,546, P<0.001). The following order, from the most to least intensely produced expression, emerged: Happiness (mean=4.51), Fear (mean=3.95), Anger (mean=3.86), Pleasant Surprise (mean=3.83), Disgust (mean=3.45), Interest/Excitement (mean=3.26), Sadness (mean=2.57), and Neutral (mean=2.52). When post hoc tests were conducted, Happiness was significantly more intense than all other expressions, and Sadness and Neutral were significantly less intense than all other expressions but did not differ from each other. In addition, Interest/Excitement was significantly less intense than Fear, Anger, and Disgust, and Disgust was significantly less intense than Fear and Anger. This effect was modified by a significant interaction between Expression and Orientation (F=3.90, df=7,546, P<0.001). The expressions of Happiness, Pleasant Surprise, and Disgust were rated more intensely in the original orientation, and the expressions of Interest/Excitement, Sadness, Fear, Anger, and Neutral were rated more intensely in the reversed orientation. When post hoc tests were conducted, orientation differences were significant for Pleasant Surprise, Fear, and Anger.

Hemiface

Although the main effect of Hemiface was not significant (P=0.618), there was a significant Hemiface by Expression interaction (F=2.61, df=7,546, P≤0.01). The left hemiface was rated as more intense for Sadness, Disgust, Interest/Excitement, and Neutral, whereas the right hemiface was rated as more intense for Happiness, Pleasant Surprise, Fear, and Anger (Table 4). On post hoc tests, all hemiface comparisons were significant except those for Happiness and Disgust. In addition, there was a significant interaction among Group, Hemiface, and Expression (F=1.79, df=14,546, P<0.05). Post hoc tests revealed that UDs were significantly lateralized for Sadness, Neutral, Interest/Excitement, and Happiness; the first three expressions were left-sided, and the fourth was right-sided. On the other hand, SZs and NCs were each significantly lateralized for only one expression: SZs, Sadness (left-sided), and NCs, Anger (right-sided).

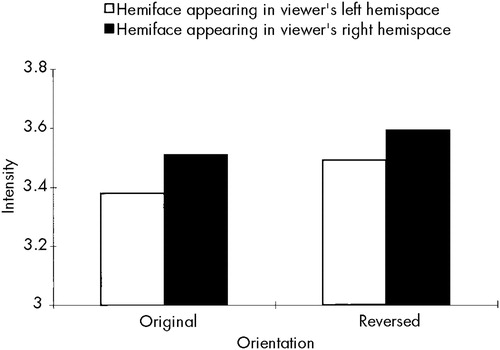

Finally, there was a significant Hemiface by Orientation interaction (F=13.14, df=1,78, P≤0.001). This finding allowed us to address reports in the literature regarding hemispace biases for processing facial emotional materials. When appearing in the original orientation, the left hemiface (mean=3.51) was rated as significantly more intense than the right hemiface (mean=3.38). Just the opposite occurred for the reversed orientation, where the right hemiface (mean=3.59) was rated as significantly more intense than the left hemiface (mean=3.49). As can be seen in Figure 1, the hemifaces appearing in the viewers' right hemispace were judged to be more intense than those appearing in their left hemispace.

DISCUSSION

Overall, there were significant differences among subject groups, with the UDs and NCs posing more intense facial expressions than the SZs. The less intense expressions among the SZs are likely to be an important aspect of their flat affect and chronicity. This finding is consistent with an examination of spontaneous facial expression35 in which the same group of SZs responded with less intense facial expressions than normal subjects. Berenbaum and Oltmanns53 also reported decreased facial expressivity in SZs with blunted affect. In a related study,54 SZs showed impaired ability to respond to mood induction relative to healthy control subjects. Further, in an examination of childhood home videos involving adults currently diagnosed with schizophrenia,55 there was evidence of reduced responsiveness as well as poor motor coordination.

The significant interaction between Group and Expression is also of interest. Whereas the SZs' deficits in affective expression showed a diminution across emotions, difficulties for UDs were more complex and valence-specific. UDs expressed Sadness with significantly more intensity than NCs, whereas NCs expressed Happiness significantly more intensely than UDs. These results corroborate previous findings in the literature regarding diminished expression of positive relative to negative emotion as a function of depression.46,56,57

When the Hemiface variable was examined, a significant interaction with Expression revealed several interesting findings. Consistent with a number of reports in the literature,51,58–62 raters judged neutral expressions as appearing more intense on the left than the right side of the face. The overall facial asymmetry data for the individual emotions provided more support for the motoric direction hypothesis than for the right-hemisphere or valence hypothesis. As described earlier, the motoric direction hypothesis points to right-hemisphere mediation in withdrawal emotions and left-hemisphere mediation in approach emotions. We found that two of the three emotions showing a left-hemiface/right-hemisphere advantage were withdrawal emotions—Sadness and Disgust. In a similar vein, the majority of emotions (three out of four) showing a right-hemiface/left-hemisphere advantage were approach emotions—Pleasant Surprise, Happiness, and Anger. Although there were two emotions that were not in keeping with the motoric direction hypothesis, the findings for these emotions are not incompatible with the neuropsychological literature on emotion. Fear, which showed a right-hemiface advantage, may be overlapping with anxiety, which is considered in some cases63–65 to be mediated by the left hemisphere. Interest/Excitement, which showed a left-hemiface advantage, may involve aspects of arousal that are presumed to be mediated by right-hemisphere structures.66,67

To address our hypotheses regarding different degrees of lateralization in the subject groups, we examined interactions involving Group and Hemiface. Although the Group by Hemiface interaction was not significant (P=0.391), there was a significant interaction among Group, Hemiface, and Expression. Consistent with our predictions, the subjects with unipolar depression showed greater left-hemiface lateralization than the other two subject groups. This finding is consistent with research that points to an association between depression and greater activation of the anterior right hemisphere (see reviews23,68,69). For example, work with EEG has shown right-sided increases in activation in depressed subjects70 and during depressed mood induction, particularly in anterior regions.71 A study72 using SPECT also found that depressed individuals had increased right-sided frontal activation compared with control subjects.

Also consistent with our predictions, SZs were less lateralized than UDs in the degree of facial asymmetry displayed. To our knowledge, this is the first examination of facial asymmetry in flat-affect schizophrenic patients. Our finding of reduced left-sided asymmetry is compatible with the general literature on schizophrenia (see reviews16,73,74). Numerous studies have found evidence for right-hemisphere dysfunction in negative-symptom, flat-affect schizophrenia.75–78 In a PET imaging study,17 hypometabolism in the right frontal region was observed in flat-affect chronic schizophrenia.

In general, facial asymmetry studies of normal adults report left-hemiface findings (see reviews7,8,22,79–81). In the current study, the normal control subjects did not demonstrate significant left-sided asymmetry. Since right-hemisphere functions have been conjectured to decline with advancing age,82–87 one possible explanation for this finding may be the age of the normal subjects (mean=59 years). Support for this hypothesis as it pertains to emotion comes from two studies examining lateralization in the perception of emotional faces; these investigations found reduced visual-field advantages as a function of age.88,89 In a similar vein, age-related changes have been found in the ability to process emotional prosody (E. Ross, personal communication, April 10, 1998). Further, in a recent study examining intention, decreased left-ear advantages in dichotic listening were found in elderly versus younger subjects.90

There were two methodological findings of interest. The first was that expressions elicited to visual imitation were produced more intensely than those to verbal command, compatible with previous findings in the clinical literature.91,92 The second was that when Orientation was considered, the finding of a right-hemispace advantage for intensity ratings was unexpected. It may be, however, that the ratings made in this particular study, which involved extensive and lengthy training procedures, were conducted in a more analytical, detailed manner than is usually the case for ratings of facial emotional materials, which are typically done in a more impressionistic or holistic fashion. In this context, Turkewitz and Ross,93 in a study of visual-field differences in facial recognition, reported a shift in field advantages over time. According to Benton,94 these findings could be “interpreted as shifts in the strategy of information processing from a holistic (i.e., right hemisphere) approach to a serial feature detection (i.e., left hemisphere) approach, and vice versa” (p. 11). Thus, the rating procedures used in this study may have drawn more on left- than right-hemisphere functions for evaluation and perceptual processing.

Although the findings from this study are complex, they reflect the breadth of the research on laterality and emotion. Clearly, more directed work in this area is needed before a full theoretical explanation can be articulated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. Burton Angrist, Dr. Ilana Grunwald, Dr. Eric Peselow, Lawrence Pick, Rick Pouget, and Kenneth Spelke for their assistance on this project. This study was based on a master's thesis conducted by the first author at Queens College and the Graduate School of the City University of New York. The research was supported, in part, by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH37952 to New York University Medical Center and MH42172 to Queens College and by Professional Staff Congress–City University of New York Research Grant 667440 to Queens College. A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society, Galveston, TX, February 1993.

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. Intensity ratings for hemifaces appearing in the original and reversed orientations, as a function of hemispace (left vsright), across all subjects.

1 Borod JC: Cerebral mechanisms underlying facial, prosodic, and lexical emotional expression: a review of neuropsychological studies and methodological issues. Neuropsychology 1993; 7:445–463Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Bryden MP, Ley RG: Right-hemispheric involvement in the perception and expression of emotion in normal humans, in Neuropsychology of Human Emotion, edited by Hielman KM, Staz K. New York, Academic Press, 1983, pp 6–44Google Scholar

3 Heilman K, Bowers D: Neuropsychological studies of emotional changes induced by right and left hemispheric studies, in Psychological and Biological Approaches to Emotion, edited by Stein N, Leventhal B, Trabasso T. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1990, pp 97–113Google Scholar

4 DeJong RN: The Neurologic Examination: Incorporating the Fundamentals of Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology. Hagerstown, MD, Harper and Row, 1979Google Scholar

5 Kuypers HGJM: Corticobulbar connections to the pons and lower brainstem in man. Brain 1958; 81:364–390Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Rinn W: Neuropsychology of facial expression, in Fundamentals of Nonverbal Behavior, edited by Feldman RS, Rimé B. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp 3–30Google Scholar

7 Borod JC, Haywood CS, Koff E: Neuropsychological aspects of facial asymmetry during emotional expression: a review of the normal adult literature. Neuropsychol Rev 1997; 7:41–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Campbell R: Asymmetries of facial action: some facts and fancy of normal face movement, in The Neuropsychology of Face Perception and Facial Expression, edited by Bruyer R. Hillside, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1986, pp 247–267Google Scholar

9 Borod JC: Interhemispheric and intrahemispheric control of emotion: a focus on unilateral brain damage. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:339–348Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Davidson RJ: Affect, cognition, and hemispheric specialization, in Emotion, Cognition and Behavior, edited by Izard CE, Kagan J, Zajonc R. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1984, pp 320–365Google Scholar

11 Schnierla T: An evolutionary and developmental theory of motivation underlying approach and withdrawal. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation 1959; 7:1–42Google Scholar

12 Kinsbourne M: Hemispheric specialization and the growth of human understanding. Am Psychol 1982; 37:411–420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Abrams R, Taylor MA: Differential EEG patterns in affective disorder and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:1355–1358Google Scholar

14 Flor-Henry P: Lateralized temporal-limbic dysfunction and psychopathology. Ann NY Acad Sci 1976; 288:777–795Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Schweitzer L: Differences in cerebral lateralization among schizophrenic and depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry 1979; 14:721–733Medline, Google Scholar

16 Cutting J: The role of right hemisphere dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160:583–588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Wolkin A, Sanifilipo M, Wolf A, et al: Negative symptoms and hypofrontality in chronic schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:959–965Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Bruder GE: Dichotic listening laterality in schizophrenia and affective disorders, in Laterality and Psychopathology, edited by Flor-Henry P, Gruzelier J. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1983Google Scholar

19 Lerner J, Nachshon I, Carmon A: Response of paranoid and nonparanoid schizophrenics in a dichotic listening task. J Nerv Ment Dis 1977; 164:247–252Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Nelson DV, Maxwell JK, Townes BD: Cerebral laterality and interhemispheric relations in schizophrenia and affective disorders. Paper presented at the meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society, Denver, CO, 1986Google Scholar

21 Davidson RJ, Schaffer CE, Saron C: Effects of lateralized presentations of faces on self-reports of emotion and EEG asymmetry in depressed and non-depressed subjects. Psychophysiology 1985; 22:353–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Borod JC, Koff E: Asymmetries in affective facial expression: behavior and anatomy, in The Psychology of Affective Development, edited by Fox N, Davidson R. Hillside, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1984, pp 293–323Google Scholar

23 Coffey CE: Cerebral laterality and emotion: the neurology of depression. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 28:197–219Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Feinberg TE, Rifkin A, Schaffer C, et al: Facial discrimination and emotional recognition in schizophrenia and affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:276–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Jaeger J, Borod JC, Peselow E: Depressed patients have atypical hemispace biases in the perception of emotional chimeric faces. J Abnorm Psychol 1987; 96:321–324Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Knox K: An investigation of nonverbal behavior in relation to hemispheric dominance. Unpublished master's thesis, University of California, San Francisco, CA, 1972Google Scholar

27 Lynn JG, Lynn DR: Face-hand laterality in relation to personality. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 1938; 33:291–322Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Levy J, Heller W, Banich M, et al: Asymmetry of perception in free viewing of chimeric faces. Brain Cogn 1983; 2:409–419Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Borod JC, St Clair J, Koff E, et al: Perceiver and poser asymmetries in processing facial emotion. Brain Cogn 1990; 13:167–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Coren S, Porac C, Duncan PA: A behaviorally validated self-report inventory to assess four types of lateral preferences. J Clin Neuropsychol 1979; 1:55–64Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773–782Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Mattis, S: Mental Status Examination for organic mental syndrome in the elderly patient, in Geriatric Psychiatry, edited by Bellak L, Karasu T. New York, Grune and Stratton, 1976Google Scholar

34 Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised. New York, Psychological Corporation, 1981Google Scholar

35 Martin C, Borod J, Alpert M, et al: Spontaneous expression of facial emotion in schizophrenia and right brain-damaged patients. J Commun Disord 1990; 73:287–301Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Borod JC, Welkowitz J, Alpert M, et al: Parameters of emotional processing in neuropsychiatric disorders: conceptual issues and a battery of tests. J Commun Disord 1990; 23:247–271Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Crow TJ: Molecular pathology of schizophrenia: more than one disease process? British Medical Journal 1980; 280:66–68Google Scholar

38 Andreasen NC: The Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms. Iowa City, IA, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

39 Lewine R, Fogg L, Meltzer H: The development of scales for assessment of positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1983; 9:368–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 Abrams R, Taylor MA: A rating scale for emotional blunting. Am J Psychiatry 1979; 135:226–229Google Scholar

41 Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC: Social Class and Mental Illness. New York, Wiley, 1958Google Scholar

43 Borod JC, Caron HS: Facedness and emotion related to lateral dominance, sex, and expression type. Neuropsychologia 1980; 18:237–241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 Borod JC, Koff E, White B: Facial asymmetry in posed and spontaneous expressions of emotion. Brain Cogn 1983; 2:165–175Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 Borod JC, Koff E, Lorch MP, et al: The expression and perception of facial emotion in brain-damaged patients. Neuropsychologia 1986; 24:169–180Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 Jaeger J, Borod JC, Peselow E: Facial expression of positive and negative emotions in patients with unipolar depression. J Affect Disord 1986; 11:43–50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 Ekman P, Friesen W: Pictures of Facial Affect. Palo Alto, CA, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1976Google Scholar

48 Oldfield RC: The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh Inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971; 9:97–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 Jaeger J: The neuropsychology of emotion in major depressive disorder. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Yeshiva University, New York, NY, 1984Google Scholar

50 Sackeim HA, Weiman AL, Forman BD: Asymmetry of the face at rest: size, area, and emotional expression. Cortex 1984; 20:165–178Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 Moreno CR, Borod JC, Welkowitz J, et al: Lateralization for the expression and perception of facial emotion as a function of age. Neuropsychologia 1990; 28:199–209Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 Ekman P, Friesen W: Unmasking the Face: A Guide to Recognizing Emotions from Facial Cues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1975Google Scholar

53 Berenbaum H, Oltmanns TF: Emotional experience and expression in schizophrenia and depression. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101:37–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 Schneider F, Gur RC, Gur RE, et al: Emotional processing in schizophrenia: neurobehavioral probes in relation to psychopathology. Schizophr Res 1995; 17:67–75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55 Walker EF, Lewine RJ: Prediction of adult-onset schizophrenia from childhood home movies of the patients. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1052–1056Google Scholar

56 Berenbaum H: Posed facial expressions of emotion in schizophrenia and depression. Psychol Med 1992; 22:929–937Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57 Levin S, Knight RA, Hall JA, et al: Verbal and nonverbal expressions of affect in speech of schizophrenic and affective disorder patients. J Abnorm Psychol 1985; 94:487–497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58 Borod JC, Kent J, Koff E, et al: Facial asymmetry while posing positive and negative emotions: support for the right hemisphere hypothesis. Neuropsychologia 1988; 26:759–764Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59 Campbell R: Asymmetries in interpreting and expressing a posed facial expression. Cortex 1978; 1:327–342Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Kowner R: Laterality in facial expressions and its effect on attributions of emotion and personality: a reconsideration. Neuropsychologia 1995; 33:539–559Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61 Mandal MK, Asthana HS, Madan SK, et al: Hemifacial display of emotion in the resting face. Behavioral Neurology 1992; 5:169–171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62 Schwartz GE, Ahern GL, Brown S: Lateralized facial muscle response to positive and negative emotional stimuli. Psychophysiology 1979; 16:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63 Tucker DM: Developing emotions and cortical networks. Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology: Developmental Behavioral Neuroscience 1991; 24:75–128Google Scholar

64 Tucker DM, Antes JR, Stenslie CE, et al: Anxiety and lateral cerebral function. J Abnorm Psychol 1978; 87:380–383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65 Tucker DM, Liotti M: Neuropsychological mechanisms of anxiety and depression, in Handbook of Neuropsychology, edited by Boller F, Grafman J. Amsterdam, Elsevier Science, 1989, pp 443–475Google Scholar

66 Heilman K, Bowers D, Valenstein E: Emotional disorders associated with neurologic diseases, in Clinical Neuropsychology, edited by Heilman KM, Valenstein E. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993, pp 461–522Google Scholar

67 Heller W: Neuropsychological mechanisms of individual differences in emotion, personality, and arousal. Neuropsychology 1993; 7:476–489Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Borod J: Emotional disorders (emotion), in The Blackwell Dictionary of Neuropsychology, edited by Beaumont JG, Kenealy PM, Rogers MJC. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Publishers, 1996, pp 312–320Google Scholar

69 Otto MW, Yeo RA, Dougher MJ: Right hemisphere involvement in depression: toward a neuropsychological theory of negative affective experiences. Biol Psychiatry 1987; 22:1201–1215Google Scholar

70 von Knorring L: Interhemispheric EEG differences in affective disorders, in Laterality and Psychopathology, edited by Flor-Henry P, Gruzelier J. New York, Elsevier Science, 1983, pp 315–326Google Scholar

71 Tucker DM, Stenslie CE, Roth RS, et al: Right frontal lobe activation and right hemisphere performance: decrement during a depressed mood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:169–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72 Reischies FM, Hedde JP, Drochenir R: Clinical correlates of cerebral blood flow in depression. Psychiatry Res 1989; 29:323–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73 Alpert M, Martz MJ: Cognitive views of schizophrenia in light of recent studies of brain asymmetry, in Psychopathology and Brain Dysfunction, edited by Shagass C, Gershon S, Friedhoff AJ. New York, Raven, 1977, pp 1–13Google Scholar

74 Venables PH: Primary dysfunction and cortical lateralization in schizophrenia, in Functional States of the Brain and Their Determinants, edited by Koukkov MM, Lehrman D, Angst J. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1980, pp 243–264Google Scholar

75 Gruzelier J, Manchanda R: The syndrome of schizophrenia: relations between electrodermal response, lateral asymmetries, and clinical ratings. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 141:488–495Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76 MacPherson FM, Barden V, Hay AJ, et al: Flattening of affect and personal constructs. Br J Psychiatry 1970; 116:39–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77 Mayer M, Alpert M, Stastney P, et al: Multiple contributions to the clinical presentation of flat affect in schizophrenic populations. Schizophr Bull 1985; 11:420–426Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78 Oepen G, Funfgeld M, Holl T, et al: Emotion-triggered changes of task-related hemispheric processing asymmetries in schizophrenics. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society, Washington, DC, 1987Google Scholar

79 Borod J, Koff E, Yecker S, et al: Facial asymmetry during emotional expression: gender, valence, and methods. Neuropsychologia 1998; 36:1209–1215Google Scholar

80 Sackeim HA, Gur RC: Facial asymmetry and the communication of emotion, in Social Psychophysiology, edited by Cacioppo JT, Petty, RE. New York, Guilford, 1983, pp 307–352Google Scholar

81 Skinner M, Mullen B: Facial asymmetry in emotional expression: a meta-analysis of research. Br J Soc Psychol 1991; 30:113–124Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Albert MS, Kaplan E: Organic implications of neuropsychological deficits in the elderly, in New Directions in Memory and Aging: Proceedings of the George A. Talland Memorial Conference, edited by Poon LW, Fozard LS, Cermak LS, et al. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1980, pp 403–432Google Scholar

83 Borod J, Goodglass H: Hemispheric specialization and development, in Language and Communication in the Elderly, edited by Obler LK, Albert M. Lexington, MA, Heath, 1980, pp 91–103Google Scholar

84 Brown J, Jaffe J: Hypothesis on cerebral dominance. Neuropsychologia 1975; 13:107–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

85 Ellis RJ, Oscar-Berman M: Alcoholism, aging, and functional cerebral asymmetries. Psychol Bull 1989; 106:128–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

86 Meudell PR, Greenhalgh M: Age related differences in left and right hand skill and in visuo-spatial performance: their possible relationships to the hypothesis that the right hemisphere ages more rapidly than the left. Cortex 1987; 23:431–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87 Mitrushina M, Fogel T, D'Elia L, et al: Performance on motor tasks as an indication of increased behavioral asymmetry with advancing age. Neuropsychologia 1995; 33:359–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

88 McDowell C, Harrison D, Demaree H: Is right-hemisphere decline in the perception of emotion a function of aging? Int J Neurosci 1994; 79:1–11Google Scholar

89 Sackeim HA, Putz E, Vingiano W, et al: Lateralization in the processing of emotionally laden information, I: normal functioning. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1988; 1:97–110Google Scholar

90 Alden JD, Harrison DW, Snyder KA, et al: Age differences in intention to left and right hemispace using a dichotic listening paradigm. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1997; 10:239–242Medline, Google Scholar

91 Brown J: Aphasia, Apraxia, and Agnosia. Springfield, IL, Charles C Thomas, 1972Google Scholar

92 Kent J, Borod J, Koff E, et al: Posed facial expression in brain-damaged patients. Int J Neurosci 1988; 43:81–87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

93 Turkewitz G, Ross P: Changes in visual field advantage for facial recognition. Cortex 1983; 19:179–185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

94 Benton A: The Hécaen-Zangwill legacy: hemispheric dominance examined. Neuropsychol Rev 1991; 2:267–280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar