Use of Clozapine in 10 Mentally Retarded Adults

Abstract

The cost, side effect profile, and required weekly blood draws associated with clozapine may dissuade some clinicians from prescribing this atypical neuroleptic to mentally retarded patients. All publications on clozapine use in mentally retarded patients are reviewed and the treatment of 10 such patients is described, bringing the total number of published cases to 84. Clozapine is efficacious and well tolerated in this population and should be considered for those patients with psychosis or bipolar illness who are intolerant of or unresponsive to other agents.

Antipsychotic drugs are commonly used to treat psychosis, self-injurious behavior (SIB), and aggression in mentally retarded (MR) patients. Despite efforts to reduce use of these drugs in this population,1 some MR patients require maintenance neuroleptics. Bipolar and psychotic patients who fail to tolerate or benefit from conventional neuroleptics often improve with clozapine, so this drug should be a logical consideration for MR patients with similar conditions. Prescription of psychotropics in this population, however, often requires that extensive informed-consent materials be provided to patients, legal guardians, and overseeing human rights committees. The paucity of published recent experience with this drug in MR patients may discourage some patients and clinicians from considering clozapine for this population. We review the literature on the use of clozapine in MR patients and describe our experience with this drug in 10 mentally retarded individuals.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

We performed medline and PsycINFO searches, obtained additional references from the bibliographies of relevant articles, and located 13 reports on the open-label use of clozapine for trials lasting from 1 day to 18 months in 74 patients with borderline-profound MR.2–14 Of this group, 59 had no other psychiatric diagnosis and clozapine was prescribed as a nonspecific treatment for aggression and SIB; diagnoses in the remainder included schizophrenia (n=9), schizoaffective disorder (n=3), bipolar disorder (n=2), and schizophreniform disorder (n=1). Case reports of 3 of the 74 patients described adverse effects, but not therapeutic response.4–6

Aggression, SIB, psychosis, and tardive dyskinesia (TD), the most commonly cited indications for treatment, improved in 86% of patients during treatment with clozapine in doses ranging from 25 to 600 mg/day. Most reports did not clarify which symptoms improved most in which patients. Aggression and self-abuse occasionally improved even without remission of psychotic symptoms.8,10

Epilepsy is common in MR patients, and seizures are associated with clozapine use. Of 9 MR epileptic patients treated with clozapine in the reports reviewed, 6 were treated concurrently with anticonvulsants.3,11 Having been seizure-free without anticonvulsants for many years, 1 patient developed seizures 1 year after starting 225 mg/day of clozapine.10 Valproic acid (VPA) was added, and this patient continued on clozapine for 6 months without further seizures.

Common side effects of clozapine reported in this population included sedation, hypersalivation, and orthostasis. More serious reported side effects included dose-related periodic cataplexy,11 neuroleptic malignant syndrome4 (although attribution to clozapine has been questioned10), priapism5 (although attribution to clozapine is unclear because of simultaneous treatment with haloperidol), pancreatitis,6 and fecal impaction with supraventricular tachycardia in a patient concurrently treated with oxybutynin.10

These reports have several important limitations: 1) the trials were all open label; 2) some reports provided insufficient data on concurrent medications, clozapine dosage, and indications for treatment; 3) outcome measures were quite variable and often not standardized; 4) VPA was started concurrently with clozapine in two patients, making attribution of clinical benefits to clozapine suspect; 5) only 2 patients had profound MR; 6) duration of follow-up was either unstated or ill defined in 5 reports.

Particularly because 51 of the patients were described in fairly impressionistic reports from the mid-1970s,2,3 questions remained. First, how safe and well tolerated is clozapine in MR patients? Second, how effective is clozapine in this population? Third, for how long is the drug effective? We therefore add our experience, which provides some of the longest follow-up described to date, to the sparse literature on this topic.

METHODS

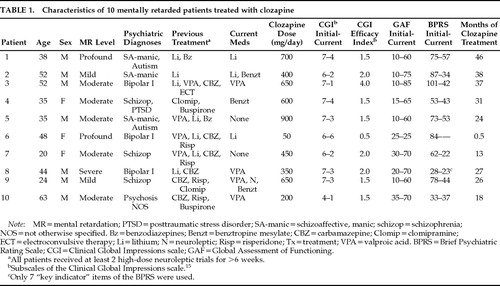

We reviewed the charts of all 10 MR patients we have treated with clozapine in institutional and community group homes. We made direct observations throughout the period of treatment (range 0.5–46 months; Table 1). Outcome measures were the Clinical Global Impressions scale (CGI),15 Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF), and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).8

Indications for treatment were psychosis or mania that had not responded to previous medications. Patient 10 was functioning well psychiatrically on fluphenazine, but he was started on clozapine because of severe TD that impaired his ability to ambulate.

RESULTS

Treatment Response

One patient (#6) discontinued the drug after 2 weeks because of neutropenia; her complete blood count normalized thereafter. This patient was therefore excluded from further analysis. Changes in CGI, GAF, and BPRS were assessed with a two-tailed t-test for equal and related samples by using the Instat statistical program. The average CGI severity rating for the remaining 9 patients dropped significantly, from a mean of 6.4 at the start of treatment, which indicates “severely ill,” to “among the most extremely ill patients in this population”15 to a mean of 2.6, which indicates “borderline to mildly ill” (P<0.0001). At the end of treatment, the average CGI efficacy index15 was 1.9, which indicates moderate to marked improvement from the drug, with side effects that “do not significantly interfere with the patient's functioning.” GAF ratings increased an average of 51 points, from an initial average of 17 to a current average of 68; this difference also was statistically significant (P<0.0001). BPRS scores for the 8 patients who did not respond well to conventional neuroleptics (excluding Patient 10, who had responded well to antipsychotics but had disabling TD, and excluding Patient 6, who developed neutropenia) also improved significantly, from a mean of 66 to a mean of 39 (P<0.0069).

Five of our patients had moderate to severe TD prior to starting clozapine; 2 experienced moderate and 3 marked improvement of TD after starting clozapine (as determined by informal clinical assessments). Patient 10's disabling TD remitted almost entirely within weeks of starting clozapine.

Side Effects

Side effects included sedation and hypersalivation in half of the patients, but these symptoms were dose dependent, transient, and not sufficient to terminate treatment. The theoretical neurotoxicity8 of clozapine in moderately to profoundly retarded patients (that is, accentuation of cognitive deficits due to the drug's anticholinergic and sedating properties) was not observed in our patients.

Four patients took VPA concurrently with clozapine (Table 1). VPA was given for seizure prophylaxis before clozapine was started in Patient 9, so the improvements observed cannot be definitively attributed to clozapine. Similar confounding of drug effects due to simultaneous initiation of VPA with clozapine also occurred in 2 of the 9 epileptic patients in previous reports.11 One patient (#10) developed drop attacks; addition of VPA eliminated these.

Patient 1 had asymptomatic Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) pre-excitation syndrome noted on ECG before and after beginning clozapine. His most recent ECG is completely normal, but spontaneous resolution of ECG changes in WPW often occurs and was probably not due to treatment with clozapine in our patient. This is the first report describing the use of clozapine in a patient with WPW; although clozapine has been associated with a variety of cardiovascular side effects, the presence of WPW should not contraindicate the use of clozapine.

CONCLUSION

Data from our patient series and from previously reported cases suggest that clozapine is well tolerated and efficacious for psychosis and mania in MR patients and that it may improve aggression and SIB independent of psychiatric diagnosis. Effectiveness does not appear to diminish over time. Although the duration of treatment described, 13–46 months, was probably sufficient to minimize the impact of placebo effects, our experience, like that of previous reports, is merely anecdotal. Controlled studies are needed to establish the safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of this drug in this population. Clozapine is a unique drug, distinct from other neuroleptics, and MR patients with treatment-refractory aggression or SIB, especially if associated with bipolar illness, psychosis, or tardive dyskinesia, should be considered for treatment with this drug.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dewey Walker, M.D., for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

|

1. Luchins DJ, Dojka DM, Hanrahan P: Factors associated with reduction in antipsychotic medication dosage in adults with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard 1993; 98:165–172Medline, Google Scholar

2. Vyncke J: The treatment of behavior disorders in idiocy and imbecility with clozapine. Pharmacopsychiatry 1974; 7:225–229Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Hemphill RE, Pascoe FD, Zabow T: An investigation of clozapine in the treatment of acute and chronic schizophrenia and gross behavior disorders. S Afr Med J 1975; 49:2121–2125Medline, Google Scholar

4. DasGupta K, Young A: Clozapine-induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:105–107Medline, Google Scholar

5. Zeigler J, Behar D: Clozapine-induced priapism. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:272–273Medline, Google Scholar

6. Martin A: Acute pancreatitis associated with clozapine use (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:714Medline, Google Scholar

7. Ratey JJ, Leveroni C, Kilmer D, et al: The effects of clozapine on severely aggressive psychiatric inpatients in a state hospital. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:219–223Medline, Google Scholar

8. Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF, Kenny JT, et al: The use of clozapine in borderline-intellectual-functioning and mentally retarded schizophrenic patients. Compr Psychiatry 1994; 35:28–33Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Mozes T, Toren P, Chernauzen N, et al: Clozapine treatment in very early onset schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:65–70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Pary RJ: Clozapine in three individuals with mild mental retardation and treatment-refractory psychiatric disorders. Ment Retardation 1994; 32:323–327Medline, Google Scholar

11. Cohen SA, Underwood MT: The use of clozapine in a mentally retarded and aggressive population. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:440–444Medline, Google Scholar

12. Burke MS, Josephson A, Sebastian CS, et al: Clozapine and cognitive function. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:127–128Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Duffy JD, Kant R: Clinical utility of clozapine in 16 patients with neurological disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:92–96Link, Google Scholar

14. Holzer JC, Jacobson SA, Folstein MF: Treating compulsive self-mutilation in a mentally retarded patient (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:133Medline, Google Scholar

15. National Institute of Mental Health: Clinical global impressions. Psychopharmacol Bull 1985; 22:839–843Google Scholar