SPECT Scans in Identical Twins With Trichotillomania

Abstract

SPECT scans of a set of twins with trichotillomania showed that the twin with more severe disease had larger perfusion defects, involving more areas on the scan. Prospective brain imaging studies of twins may provide useful information about the neurobiology of trichotillomania and other obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders.

Trichotillomania (TTM) is a disorder of chronic hairpulling that affects up to 2.5% of the population.1,2 Although its phenomenology has been well described, relatively little is known about the neurobiology of the disorder. Overlap in phenomenology and pharmacotherapy response with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) has led to the suggestion that trichotillomania is related to this disorder, but not all data are consistent. Several reports of familial trichotillomania exist, but the nature of any putative genetic component is unknown.3–6 Although there are a number of interesting preliminary brain imaging findings in TTM, there have been few replication studies.7,8

We present the cases of a pair of identical twins with trichotillomania and discuss their SPECT scan findings in light of previous neuroimaging findings.

CASE REPORT

Mrs. A. and Mrs. B. are 31-year-old identical twins of Afrikaner descent who presented to our research unit with hairpulling, which in both met DSM-IV criteria for trichotillomania. Mrs. B.'s pulling had started at the age of 11, and Mrs. A.'s a year later. No precipitating factors were recalled. The two sisters exhibited similar styles of pulling: pulling occurred only from the scalp, and a preference was shown for coarse hairs. Both pulled more frequently in the evening and in response to sadness or relaxation, and both experienced increased premenstrual pulling. Mrs. B., however, had more severe symptoms than her sister: she pulled from more sites and had more episodes of pulling per day. Pulling was followed by oral behaviors involving hair; Mrs. B. usually would bite and swallow the hair. Mrs. B.'s hairpulling had more impact on her life than did her sister's; Mrs. B. had several bald spots and consequently avoided hairdressers and other situations where her hair might be noticed. She also experienced more shame and guilt after pulling.

Neither sister had a history of or a current diagnosis of OCD or a tic disorder. Mrs. A., however, had a history of recurrent episodes of major depression, beginning at age 12, concurrently with the onset of her trichotillomania. At the time of presentation, however, there was no major depression. Her last major depressive episode had resolved approximately 3 months before the scan.

Both sisters underwent cerebral perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) after informed consent was obtained for the procedure. At the time of the scan, both patients were treatment-naive. The injection for the SPECT studies was performed at rest, with the eyes open, using technetium-99m hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime as the imaging agent. Both patients were asked to allow themselves to feel the urge to pull during the scanning, so as to simulate the feeling that they experienced during their usual episodes.

The two separate scans were both normalized for intensity, using the cerebellum as a reference area. Therefore, the cerebellar activity was set to a fixed value for both scans, and the rest of the scan intensity was scaled proportionally. Equivalent slices were lined up by hand and comparison done by visual inspection. No use of mathematical co-registration or subtraction techniques was involved.

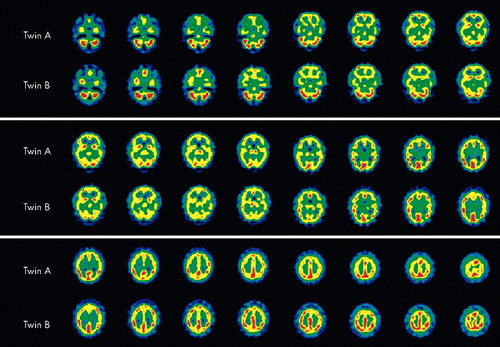

Both SPECT scans showed perfusion abnormalities (Figure 1). Mrs. A.'s scan showed decreased perfusion in both anteromedial temporal lobes. Mrs. B.'s scan also showed decreased perfusion in the temporal lobes, but here the anteromedial aspect of the right temporal lobe and almost the entire left lobe with the exclusion of the posterolateral part were involved.

In general, both twins had good perfusion of the frontal lobes. Mrs. A. showed small focal perfusion defects in the paracingular cortex, more prominent on the left than the right, as well as a focal area of higher blood flow anterolaterally on the right. Mrs. B. showed a similar area of high perfusion; however, hers was more prominent. In addition, a focal perfusion defect anterolaterally in the left frontal lobe was noted.

Both twins showed higher perfusion on high cuts of the parietal cortex, this being more pronounced on the right. However, in Mrs. B. this difference was more pronounced than in her sister. She also had small focal perfusion defects in the left temporoparietal cortex and left parieto-occipital cortex.

DISCUSSION

These findings suggest that more severe trichotillomania is associated with more extensive and pronounced perfusion abnormalities on SPECT scan. To our knowledge, this is the first report on twins with trichotillomania suggesting that severity of hairpulling symptoms may be linked to the extent and degree of cerebral abnormalities. Studies in twins with Tourette's syndrome, however, have suggested that symptom severity is associated with more abnormalities on morphological brain imaging. Hyde et al.9 found that more severely affected twins with Tourette's showed smaller right caudate and left lateral ventricle volumes on morphometric MRI.

Our SPECT findings are consistent in part with previous neuroimaging studies in trichotillomania,7,10 which have shown abnormalities in the parietal, frontal, and occipital areas. In a PET imaging study,10 however, normalized left caudate and normalized right cerebellum metabolic activity was inversely correlated with severity of trichotillomania; that is, lower metabolic rates were associated with worse disease. Neither of our patients showed abnormalities in these areas.

Of note is the involvement of the temporal lobes. Both subjects show involvement of the medial temporal lobe, and the more severely affected twin shows more temporal involvement. Although no previous studies have mentioned temporal lobe abnormalities in trichotillomania, several studies have shown temporal lobe dysfunction in OCD.11–14 In OCD, it has been postulated that medial temporal lobe recruitment results from a failure of filtering at the level of the thalamus, allowing information that is usually subconsciously processed to gain access to consciousness, where it is experienced as intrusive phenomena.15 In this model, tics or compulsions serve as compensatory mechanisms by facilitating filtering at the level of the thalamus. In view of our findings it is tempting to speculate that similar pathology is present in trichotillomania. The more severe temporal lobe involvement in the more severely affected twin may represent more information gaining access to consciousness, a greater need for thalamic gating, and hence a greater urge to pull. One caveat, however, is that in the above-mentioned study patients were not scanned during an implicit processing task, and one must therefore be cautious when extrapolating these results.

Abnormalities in the parietal lobe have occasionally been found in imaging studies of OCD.12,16,17 However, only one other report10 found parietal lobe abnormalities in trichotillomania. An increasing body of evidence suggests the parietal lobe may contain a repertoire of learned movement programs. It is possible that an imbalance in the frontoparietal circuits leads to disinhibition of some of these movement programs, and to resultant stereotypical movements.18,19 This would be in keeping with the observation that pulling in trichotillomania is often described as “automatic,”20 and also with the increased perfusion to the parietal cortex noted in both patients. It is interesting to note that, again, the twin with more severe symptoms exhibited more changes on SPECT scan.

The cases presented indicate that functional brain imaging studies in twins may provide useful information about the neurobiology of trichotillomania and other OCD spectrum disorders, and that more such studies are warranted. Furthermore, the urge to pull may be mediated by cortical as well as striatal dysfunction, and severity of symptoms may be associated with more widespread cortical dysfunction. Given that we examined only a single twin pair, definitive conclusions cannot, however, be drawn from our findings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Vythilingum, Dr. Stein, Ms. van Kradenburg, and Ms. Hugo are supported by the Medical Research Council of South Africa.

FIGURE 1. Brain SPECT scans for Twin A and Twin B. Colors represent spectrum of cerebral perfusion, red being most perfused, white and blue least perfused.

1 Christenson GA, Mackenzie TB, Mitchell JE: Characteristics of 60 adult chronic hairpullers. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:365-370Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Rothbaum B, Shaw L, Morris R, et al: Prevalence of trichotillomania in a college freshman population (letter). J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:72Medline, Google Scholar

3 Delgado RA, Mannino FV: Some observations on trichotillomania in children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1960; 8:229-246Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Galski T: Hairpulling (trichotillomania). Psychoanal Rev 1983; 70:331-346Medline, Google Scholar

5 Kerbeshian J, Burd L: Familial trichotillomania (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:684-685Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Christenson GA, Mackenzie TB, Reeve EA: Familial trichotillomania (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:283Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Grachev ID: MRI-based morphometric topographic parcellation of human neocortex in trichotillomania. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 1997; 51:315-321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Stein DJ, Coetzer R, Lee M, et al: Magnetic resonance brain imaging in women with obsessive-compulsive disorder and trichotillomania. Psychiatry Res 1997; 74:177-182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Hyde TM, Stacey ME, Coppola R, et al: Cerebral morphometric abnormalities in Tourette's syndrome: a quantitative MRI study of monozygotic twins. Neurology 1995; 45:1176-1182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Swedo SE, Rapoport JL, Leonard HL, et al: Regional cerebral glucose metabolism of women with trichotillomania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:828-833Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Silverman JS, Loychik SG: Brain mapping abnormalities in a family with 3 obsessive-compulsive children. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1990; 2:319-322Link, Google Scholar

12 Lucey JV, Costa DC, Blanes T, et al: Regional cerebral blood flow in obsessive-compulsive disordered patients at rest: differential correlates with obsessive compulsive and anxious avoidant dimensions. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167:629-634Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Berthier ML, Kulisevsky J, Gironell A, et al: Obsessive-compulsive disorder associated with brain lesions: clinical phenomenology, cognitive function and anatomic correlates. Neurology 1996; 47:353-361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Moriarty J, Eapen V, Costa DC, et al: HMPAO SPET does not distinguish obsessive-compulsive and tic syndromes in families multiply affected with Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Psychol Med 1997; 27:737-740Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Rauch SL, Savage CR, Alpert NM, et al: A PET investigation of implicit and explicit sequence learning. Hum Brain Mapp 1995; 3:271-286Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Horwitz B, Swedo SE, Grady CL, et al: Cerebral metabolic pattern in obsessive-compulsive disorder: altered intercorrelations between regional rates of glucose utilization. Psychiatry Res 1991; 40:221-237Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Rubin RT, Villanueva-Meyer J, Ananth J, et al: Regional xenon-133 cerebral blood flow and cerebral technetium-99m HMPAO uptake in unmedicated patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and matched normal control subjects: determination by high-resolution single-photon emission computed tomography. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:695-702Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Snyder LH, Batista AP, Anderson RA: Intention-related activity in the posterior parietal cortex: a review. Vision Res 2000; 40:1433-1441Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Vilensky J, Gilman S: Positive and negative factors in movement control: a current review of Denny-Brown's hypothesis. J Neurol Sci 1997; 151:149-158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Christenson GA, Mackenzie TB: Trichotillomania, in Handbook of Prescriptive Treatments for Adults, edited by Hersen M, Ammerman RT. New York, Plenum, 1994, pp 217-235Google Scholar