Fahr's Disease and Schizophrenia in a Patient With Secondary Hypoparathyroidism

SIR: Fahr's disease is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by extensive cerebral calcification. Some have suggested that Fahr's disease produces psychosis,1 while others consider any association between Fahr's disease and psychosis coincidental.2,3 We present a case of Fahr's disease and schizophrenia in which there was clearly no etiologic relationship between the two conditions.

Case Report

This white female with normal developmental milestones graduated from 8th grade at age 14 and married at age 15. At 26, she experienced severe auditory hallucinations, followed by tactile hallucinations, restlessness, paranoia, and bizarre somatic delusions. Her symptoms ameliorated at age 41 with the introduction of chlorpromazine. At 46, she underwent thyroidectomy for toxic goiter. She was discharged to family care, and for most of her 50s she served as caretaker to an elderly woman while continuing antipsychotic medication. At age 62, after the death of her employer, she was hospitalized for sexual delusions and increasingly intrusive auditory hallucinations. When discharged at age 68 to an adult home, she managed well and did housecleaning in the community. She developed severe tardive dyskinesia. At 71 she had a mastectomy for carcinoma. A year later she suffered a presumed stroke but recovered after a few weeks. CT scan revealed basal ganglia calcifications. Although her IQ dropped from 103 in her 20s to 81 in her 70s, this was attributed to slow responsiveness, and there was no suggestion of serious cognitive deterioration. She died of metastatic breast cancer at 73. The consensus diagnosis, after review of the hospital chart with the modified Diagnostic Evaluation After Death,4 was paranoid schizophrenia.

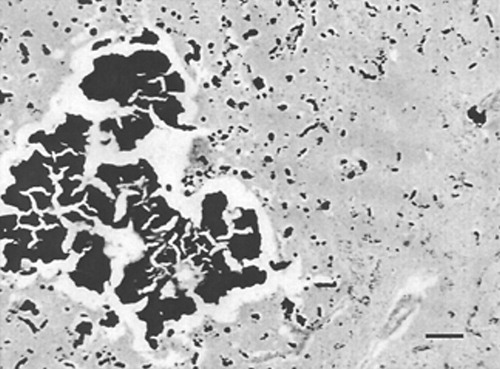

General autopsy demonstrated hepatic metastases, atherosclerosis, and thrombosis of the inferior vena cava. Two-thirds of the right lobe of the thyroid gland had been removed surgically. Parathyroid glands were not described. The brain weighed 1,050 g. The basal ganglia and cerebellar dentate nuclei were gritty and yellow. Histologically, heavy mineralizations were present in the lenticular nucleus, internal capsule, lateral caudate nucleus, thalamus, and dentate nucleus (Figure 1). Alzheimer-type changes were minimal.

Comment

Cummings et al.5 identified two types of psychiatric symptom presentation with basal ganglia mineralization. With early onset (mean age 31), psychosis was more common. With later onset (mean age 49), motor and cognitive symptoms predominated. More recent reviewers have claimed no epidemiologic association between basal ganglia mineralization and neuropsychiatric symptoms. No consistent associations with etiology, localization, volume, or symptoms have been observed.1

The current case argues against a link between basal ganglia mineralization and the symptoms of schizophrenia. The patient's first psychotic episode was long before her thyroidectomy, which led to the hypoparathyroidism that was almost certainly the cause of her brain mineralizations. Psychosis did not worsen, and there was little evidence of cognitive decline.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants MH60877, MH64168, AG08702, MH46745, MH50727; The National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression; the Theodore and Vada Stanley Foundation; and the Lieber Center for Schizophrenia Research at the Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University.

Figure 1. Large and small mineralizations in the basal ganglia. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Bar=100 microns.

1 Forstl H, Krumm B, Eden S, et al: Neurological disorders in 166 patients with basal ganglia calcification: a statistical evaluation. J Neurol 1992; 239:36-38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Flint J, Goldstein LH: Familial calcification of the basal ganglia: a case report and review of the literature. Psychol Med 1992; 22:581-595Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Forstl H, Krumm B, Eden S, et al: What is the psychiatric significance of bilateral basal ganglia mineralization? Biol Psychiatry 1991; 29:827-833Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Keilp JG, Waniek C, Goldman RG, et al: Reliability of post-mortem chart diagnoses of schizophrenia and dementia. Schizophr Res 1995; 17:221-228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Cummings JL, Gosenfeld LF, Houlihan JP, et al: Neuropsychiatric disturbances associated with idiopathic calcification of the basal ganglia. Biol Psychiatry 1983; 18:591-601Medline, Google Scholar