Hypersexuality After Right Pallidotomy for Parkinson’s Disease

Abstract

The authors describe hypersexuality following atypical right pallidotomy for intractable Parkinson’s Disease (PD). This patient and literature review suggest important roles for the pallidum in sexual behavior and dopamine in sexual arousal.

Patients with Parkinson’s Disease (PD) may develop levodopa-induced hypersexuality.1 We report a patient with profound changes in sexuality after pallidotomy surgery for PD and review the literature on possible neurological mechanisms for hypersexuality.

CASE REPORT

A 59-year-old, right-handed man underwent a right pallidotomy for PD of 16 years duration. Prior to surgery, he had left-sided rigidity and bradykinesia, left upper extremity tremor, postural instability, bradyphrenia, and hypophonia. He had moderate disability and remained independent in activities of daily living, but he could no longer work as an engineer. After the pallidotomy, his left-sided symptoms significantly improved. His past medical history included hypertension and a remote closed head injury. There was no history of psychiatric illness, unusual sexual behavior, or drug-induced behavioral changes prior to his surgery.

Immediately after the pallidotomy, the patient began demanding oral sex up to 12 to 13 times a day from his wife of 41 years. He forced her to have sex with him despite her serious cardiac condition. He masturbated frequently and propositioned his wife's female friends for sex. His antiparkinsonian medications (8 carbidopa/levodopa 25/250 mg q.d.; pramipexole 1.5mg q.i.d) were not decreased postoperatively, and his sexual behavior was worsened with drug-induced dyskinesias.

There was additional aberrant behavior. He began hiring strippers and driving around town searching for prostitutes. He spent hours on the Internet looking for sex and buying pornographic materials. At one point, his wife found him trying to sexually relieve himself while viewing a photograph of his 5-year-old granddaughter. He was later accused of touching the child inappropriately and asking her to touch his penis. His granddaughter was removed from the home by child protection services.

The patient wanted his libidinal urges to become “normalized” again. He complained of recurrent and intrusive sexual thoughts, increased sexual urges, and being “awash in hormones like an 18 year-old.” He complained that satisfying his libido had become of overwhelming importance, overshadowing all other activities and interests.

His examination did not reveal other mental status abnormalities. He did not manifest euphoria, pressured speech, or flight of ideas. He was oriented and had a digit span of 8 forward. Language was normal, and he generated word lists of 17 animals/minute and 23 “F” words/minute. His 15-minute verbal delayed recall was 7/10. He had normal constructions, calculations, alternate tapping, multiple loops, and abstractions. Neurological examination disclosed mild hypophonia, a stooped posture with decreased arm swing, mild cogwheel rigidity, a positive glabellar reflex, and a left upgoing toe not present preoperatively.

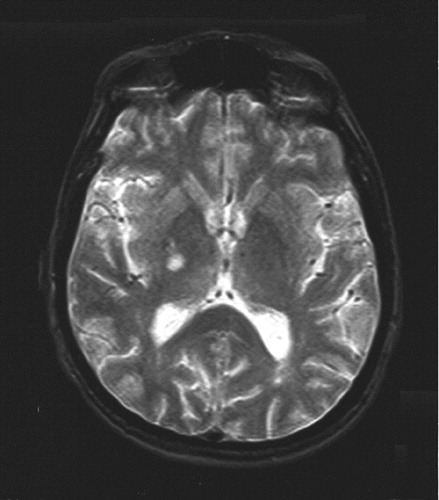

One year after his pallidotomy, the patient was reported missing for 4 days. The police found him in a motel where he had been seeking prostitutes. On admission, his mental status and neurological evaluations, including neuroimaging, were unchanged beyond evidence for his pallidotomy (Figure 1). While in the hospital, he was found sneaking into the bathroom to have sex with his wife. A taper of his anti-parkinsonian medications was begun, with a gradual decrease in his sexual behavior. He was discharged with reduction of his carbidopa/levodopa (25/250 mg) to four tablets per day and pramipexole (0.75 mg t.i.d).

Shortly after discharge, the patient's sexual behavior decreased further, but his parkinsonism worsened. His sexual activity decreased to about 6 times/day, but his speech became slighly dysarthric with a logoclonic output, bradyphrenia, and a festinating speech. Tone was increased slightly, bilaterally, but there was no tremor. Valproate (250mg b.i.d.) was started for further amelioration of his sexual behavior. At 6-month follow-up, his sexual activity had decreased to about once/week, and he had discarded all pornographic materials.

DISCUSSION

This patient had profound hypersexuality and paraphilia after an atypical pallidotomy for intractable PD. Although prior reports have noted inappropriate sexual behavior,2,3 none has described a patient with this degree of hypersexuality after pallidotomy. Compared to the usual pallidotomy scar, his lesion was more anteriorly and laterally placed in the pallidum. In addition, he had a new Babinski sign suggesting an extensive lesion affecting the capsular pyramidal tracts. The variation in placement of the pallidotomy, or its extension beyond the appropriate site, could have caused hypersexuality.

The differential diagnosis of his hypersexuality includes “secondary” mania.4 Lesions in the right hypothalamic region may result in manic behavior and hypersexuality. Drugs that facilitate monoaminergic neurotransmission can also cause secondary mania, including levodopa and dopamine agonists. Our patient, however, did not have an abnormally elevated or irritable mood or other symptoms of mania.

Hypersexuality may result from lesions in several parts of the brain. Bilateral temporal disease can produce hypersexual behavior as part of the Klüver-Bucy syndrome.5 This syndrome also includes placidity, hyperorality, visual agnosia, and a tendency to attend to any visual stimulus. Right hemisphere strokes, particularly if they involve the anteromedial temporal lobe, are more likely than left hemisphere strokes to increase libido.6 Temporal limbic seizures, especially on the right, can manifest as sexual feelings or sexual automatisms. Damage to the septal nuclei is another source of hypersexuality,7 and hypothalamic dysfunction results in periodic hypersexuality and hypersomnolence as part of the Klein-Levine syndrome.8 Finally, bilateral injury of basal frontal lobes may result in disinhibition of sexual activity.

A few studies have also shown evidence for pallidal involvement in sexual behavior. Among healthy sexually aroused men, there was increased cerebral blood flow in the ventral globus pallidus as well as the anterior cingulate and anterior temporal cortex.9 On a functional MRI study of men exposed to erotic stimuli, there was significant activation of the globus pallidus as well as the inferior frontal lobes, cingulate gyrus, corpus callosum, thalamus, caudate nuclei, and inferior temporal lobe.10

Dopamine itself has a definite role in sexual function. First, dopamine is critical to the medial preoptic anterior (MPAO) hypothalamic nuclei. MPOA activity is maximal on sexual arousal, declines with initiation of the sexual act, and decreases ejaculation.11,12 Dopamine agonists microinjected into the MPOA of male rats facilitate and dopamine antagonists inhibit sexual behavior. Second, dopamine therapy may stimulate central D2 dopaminergic projections to the nucleus accumbens involved in conveying information about the reward value of stimuli.13 Penile erections and increased libido may result from excitation of this central D2 receptor mechanism.14 Stimulation of the brain's reward system may be responsible for some PD patients' dependency on dopaminergic medications.15

In sum, this patient had increased libido and sexual arousal after an atypical pallidotomy. His hypersexuality could have resulted because part of the globus pallidus mediates sexual behavior. His sexual behavior, however, was also enhanced by his dopaminergic medications. Possible explanations include postsurgically increased dopamine, or receptor upregulation, in the MPAO neurons or increased stimulation of the central D2 dopaminergic reward system. Finally, in addition to decreasing the anti-parkinsonian drugs, treatment with other drugs, such as valproate, may further inhibit sexual behavior.16

FIGURE 1. Image of a Patient With Parkinson’s Disease Who Had Undergone a Pallidotomy

1 Lambert D, Waters CH: Sexual function in Parkinson’s Disease: Clin Neurosci 1998; 5:73–77Google Scholar

2 Shannon KM, Penn RD, Kroin JS, et al: Stereotactic pallidotomy for the treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Efficacy and adverse effects at 6 months in 26 patients. Neurology 1998; 50:434–438Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Dogali M, Fazzini E, Kolodny E, et al: Stereotactic ventral pallidotomy for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurology 1995; 45:753–761Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Mendez MF: Mania in neurological disorders. Cur Psychiaty Rep 2000; 2:440–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Lilly R, Cummings JL, Benson DF, et al: The human Kluver-Bucy syndrome. Neurology 1983; 33:1141–1145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Monga TN, Monga M, Raina MS, et al: Hypersexuality in stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1986; 67:415–417Medline, Google Scholar

7 Gorman DG, Cummings JL: Hypersexuality following septal injury. Arch Neurol 1992; 49:308–310Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Yassa R, Nair NP: The Kleine-Levine syndrome—a variant? J Clin Psychiatry 1978; 39:254–259Medline, Google Scholar

9 Rauch SL, Shin LM, Dougherty DD, et al: Neural activation during sexual and competitive arousal in healthy men. Psychiatry Res; 1999; 91:1–10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Park K, Seo JJ, Kang HK, et al.: A new potential for blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) functional MRI for evaluating cerebral centers of penile erection. Int J Impot Res 2001; 13:73–81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Dominguez J, Riolo JV, Xu Z, et al.: Regulation by the medial amygdala of copulation and medial preoptic dopamine release. J Neurosci 2001; 21:349–355Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Oomura Y, Yoshimatsu H, Aou S: Medial preoptic and hypothalamic neuronal activity during sexual behavior of the male monkey. Brain Res 1983; 266:340–343Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Becker JB, Rudick CN, Jenkins WH: The role of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and striatum during sexual behavior in the female rat. J Neurosci 2001; 21:3236–32341Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 O'Sullivan JD, Hughes AJ: Apomorphine-induced penile erections in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord 1998; 13:536–539Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Giovannoni G, O'Sullivan JD, Turner K, et al: Hedonistic homeostatic dysregulation in patients with Parkinson’s Disease on dopamine replacement therapies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 68:423–428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Paredes, Karam, Highland, et al: GABAergic drugs and socio-sexual behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1997; 58:292–298Crossref, Google Scholar