Construct Validity and Frequency of Euphoria Sclerotica in Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

Using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), we studied euphoria and other behavioral changes in 75 consecutive, unselected multiple sclerosis (MS) patients and 25 healthy controls. We also assessed disease duration, clinical course, physical disability, personality, depression, insight, cognition, and caregiver distress. Factor analysis identified a cluster of symptoms—labeled euphoria/disinhibition—similar to the euphoria sclerotica syndrome originally described by Charcot and others. The euphoria/disinhibition factor score was elevated in 9% of patients and associated with secondary-progressive course, low agreeableness, poor insight, impaired cognition, and high caregiver distress. Thus, we used the NPI to validate the euphoria syndrome in multiple sclerosis (MS) and determined its frequency, and its neurological and psychological correlates.

As noted in a recent historical review,1 euphoria and related neurobehavioral phenomena have been observed in multiple sclerosis (MS) since Charcot2 first noted that many patients exhibit a peculiar “cheerful indifference without cause.” More recent work3,4,5 suggests that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesion burden and atrophy are associated with dementia and euphoric personality change. However, while cognitive impairment in MS is well understood, there remains much uncertainty about the prevalence and scope of the euphoria syndrome.

Two recent studies attempted to measure personality and behavior change using reliable and validated instruments. Our group6 employed the NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI),7 a standardized questionnaire based on the widely recognized Five Factor Model of personality.8,9,10 Compared to healthy controls, cognitively impaired MS patients had higher degrees of neuroticism and lower degrees of extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Regression models demonstrated that informant reported decrements in altruism, a component of agreeableness, and conscientiousness were associated with cognitive (especially executive function) impairment. Similar personality changes were previously identified in patients with Alzheimer's disease.11,12 In a study of 44 MS patients, Diaz-Olavarrieta and colleagues13 found that behavioral symptoms, assessed with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) of Cummings,14 are more common in MS (95%) than in controls (16%). Patients exhibited depression most commonly, but euphoria and disinhibition were also observed.

Unfortunately, these studies were limited by small sample sizes, selection bias, and failure to account for personality, depression and behavior change in the same analysis. Thus, differences of opinion remain regarding the prevalence and scope of this neurobehavioral syndrome. Designed to address methodological problems in prior work, this study endeavored to (a) develop criteria for identifying a euphoria syndrome in MS; (b) determine the frequency of the syndrome in an unselected sample; and (c) identify other disease and psychological variables that are associated with the syndrome.

METHODS

Participants

Seventy five patients with MS between the ages of 18 and 65 were recruited consecutively from an MS clinic registry. Refusal rate was 7 percent. All patients underwent neurological examination by MS specialists and met recent consensus diagnostic criteria for MS.15 Patients were excluded if they had (a) current or past medical or psychiatrc disorder (including major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder) other than MS that could affect cognitive or psychological function; (b) abused drugs or alcohol; (c) severe motor or sensory defect that would interfere with psychometric testing; or (d) an MS relapse or corticosteroid pulse within four weeks of assessment. The majority of the sample (85%) was treated with an immunomodulatory medication (glatamir acetate, interferon beta 1a). Frequencies of other medications in the sample were as follows: anxiolytic or anticonvulsant (10% or 13%), antidepressant (17% or 23%), antipsychotic (1% or 1%), stimulants (including amantadine) (14% or 19%), pain (1% or 1%). Twenty-five healthy control volunteers were recruited via advertisement. Informants were required to have contact with the patient at least three times per week.

Measures

The NPI,14 an informant-based rating scale designed to assess psychopathology in neurological disease, was administered to informants. The NPI covers ten domains including delusions, hallucinations, agitation, dysphoria, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, and aberrant motor activity. Questions are standardized and ratings reflect changes in patient behavior following the onset of illness. Aberrant behaviors that have been present throughout life but have changed with progression of illness are also included, but unchanging chronic behavior patterns are not. Control informants were asked about the primary participant's behavior over the past four weeks.16 For each domain, informants were asked to judge the frequency of the target symptom on a 4-point scale from 1 (less than once per week) to 4 (once or more per day). Severity was rated on a 3-point scale from 1 (mild) to 3 (marked). Ten composite domain scores were calculated as the products of frequency x severity (maximum = 12). If the symptom was not present, a score of 0 was recorded. The NPI index was obtained by totaling the domain scores.

Personality was assessed with the revised version of the NEO-PI,7 a standardized, comprehensive, questionnaire-format test with well-established reliability and validity. The NEO-PI was derived from the Five-Factor Model of personality which encompasses a wide spectrum of traits comprising previously established personality models.10,17,18 We employed both patient- and informant-report administrations of the test. Only two factors were included, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Agreeableness is the desire for socialization, honesty and altruism in relationships. Conscientiousness is the proclivity to be well organized and deliberate. These domains were chosen a priori because they tap features of personality changes described in the early literature (e.g., egocentricity, low altruism or empathy, lack of regard for duty and achievement).1 In accordance with the NEO-PI manual, scores were converted to gender and age-based T scores (mean = 50, SD = 10), with higher scores indicating a stronger endorsement of each trait. Discrepancy scores, the absolute values of differences between self- and informant-reports, were calculated as measures of insight. In the NEO-PI standardization sample, and in our own work with this instrument, healthy patient/informant dyads produced scores that did not differ statistically.6,19

Two depression scales were employed. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)20 is a widely used 21-item self-report questionnaire. Because the BDI includes somatic items that overlap with neurological symptoms of MS, a 10-item version of the Center for Epidemologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D)21,22 was also used. For both, higher scores indicate greater subjective dysphoria or more depressive symptoms.

Neurological exams were performed by neurologists specializing in MS in order to derive an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)23 score and to categorize patients having a primarily relapsing-remitting or secondary progressive course. Information regarding course and disease duration was also obtained via chart review.

The MS Neuropsychological Questionnaire, a newly developed 15-item test, was used to estimate the degree of neuropsychological impairment. Informant ratings have been shown to predict cognitive impairment in MS patients.24

The NPI Caregiver Distress Index25 was used to measure informant distress. This validated index uses ratings on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely distressing), which are totaled across all NPI domains.

Procedures

The patients continued to receive their usual medical care while enrolled in the study. Informed consent was obtained, and the protocol was approved by a university review board. All participants underwent an initial telephone screening interview to evaluate inclusion criteria and confirm informant availability. Participants were evaluated in a single session of three hours (participants also underwent neuropsychological and imaging studies, analyses of which will be carried out in future reports). Neurological exams were performed within six months of the study. All participants were paid 75 US dollars.

Statistical Analyses

Group means were compared by t and chi-square tests as appropriate. Significance was accepted at a conservative p < .01 to reduce type I error. Frequency of individual behavioral symptoms on the NPI was based on a cut-off of 1 or higher.14 Exploratory factor analysis was performed with the NPI domain scores. The domains delusions and hallucinations were excluded due to zero or near zero variance and aberrant motor behavior was excluded to avoid the confounding influence of neurologic MS symptoms. After oblique rotation revealed that the emerged factors were not correlated with each other (r < .30), an orthogonal varimax rotation was performed. Variable loadings with coefficient absolute values greater than .50 were used to describe the factors. To explore relationships between NPI factors and other measures, Pearson correlations were calculated and followed by regression models.

RESULTS

Descriptive Data and Group Comparisons

Most participants were women (67% MS, 60% control) and Caucasian (86% MS, 100% control). The mean (±SD) ages were 43 (± 8) and 41 (± 8) years, for MS and controls respectively. The mean education level for both groups was 14.6 (± 2) years. Among MS patients, 44 (59%) of the informants were spouses or full-time domestic partners, 10 (13%) were parents, and 21 (28%) were other family members (e.g., siblings) or close friends. These informants had known the patients for an average of 24 (± 13) years. Among control participants, 19 (76%) of the informants were spouses, and 6 (24%) were other family members or close friends. The control informants had known the primary participants for an average of 19 (± 12) years. These characteristics did not differ significantly between the two groups (all p values > 0.6). In addition, NEO-PI and NPI ratings did not differ among informant subgroups (domestic partners, parents, other). Mean disease duration was 12 (± 7) years (range 2–44). Most patients (54% or 72%) had relapsing-remitting disease. The mean EDSS score was 3 (± 2; range 0–7.5).

There were no significant group differences on the NEO-PI. Among MS patients, mean BDI was 9.7 (± 7.4) and mean CES-D was 8.8 (± 6.1). For the control group, these values were 4.9 (± 4.2) and 4.7 (± 3.6), respectively. Mean differences were significant (BDI p = 0.004; CES-D p = 0.003). The two groups also differed significantly on the informant-rated MS Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire (p < 0.001), with higher values reported for patients (23.3 ± 13.6) vs controls (13 ± 7.8). On the NPI Caregiver Distress Index, mean distress among MS informants was 7.5 (± 7.2) compared to 1.1 (± 2.2) for controls (p < 0.001).

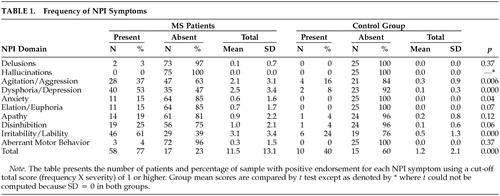

Neuropsychiatric symptoms (Table 1) were more common in patients. Most (66% or 88%) exhibited at least one behavioral disturbance and 36 patients (as compared to one control) exhibited a “marked” disorder as operationalized by Wood et al (domain score greater than 4).26 The mean MS NPI Index was 11.5 (± 13.1; median = 6, range 0–54), almost 10 times higher than the control group mean (1.2 ± 2.1, p < .001). Significant group differences were also apparent on Agitation/Aggression, Dysphoria/Depression, and Irritability/Lability (p < .01).

Factor Analysis of the Behavioral Symptoms in MS Patients

Factor analysis of NPI domain scores yielded a two-factor solution, accounting for 68% of the variance. The first factor contained agitation/aggression, euphoria, disinhibition and irritability/lability and accounted for 40% of the variance (loadings of .85, .87, .78, and .66, respectively). The domains of dysphoria/depression, anxiety and apathy emerged as the second factor, accounting for 28% of the variance (loadings .73, .70 and .73, respectively). The eigenvalues for the two factors were 3.15 and 1.66, respectively. The oblique structure matrix showed essentially the same pattern of item loadings as the orthogonal rotation. As such, two factor scores were calculated from NPI raw data. The first, the sum of the agitation/aggression, euphoria, disinhibition and irritability/lability scores, was labeled euphoria/disinhibition. This factor is descriptive of euphoria patients in the classical literature.1 The 2nd factor, labeled dysphoria/apathy, was calculated as the sum of dysphoria/depression, anxiety, and apathy domain scores.

Frequency

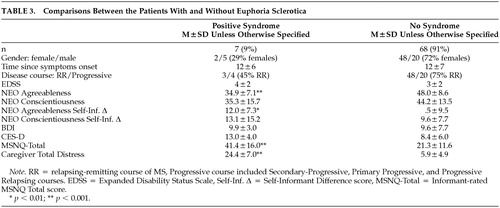

Among MS patients, the mean euphoria/disinhibition score was 6.8 (± 8.3), and the mean dysphoria/apathy score was 4.0 (± 5.5). Both were significantly higher (p < 0.001) when compared to controls (1.0 ± 1.8 and 0.2 ±0.8, respectively). The euphoria/disinhibition factor was operationalized by applying a cutoff score of 16 (four domains × 4), as suggested in prior research.26 A score >16 was judged to reflect “marked” disturbance. Seven patients, or 9% of the sample, met this standard.

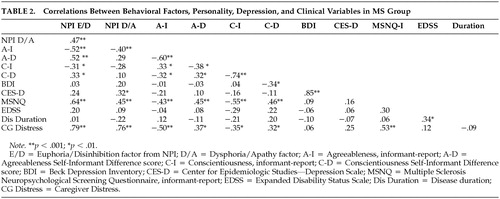

Correlates and Predictors of Behavioral Disinhibition

Pearson correlations appear in Table 2. The following clinical and demographic variables were entered into a stepwise regression model predicting euphoria/disinhibition: age, gender, education level, years informant has known patient, disease course (relapsing vs progressive), disease duration, and EDSS. In this model, only disease course emerged as a significant predictor (R2 = 0.13, p = 0.01). A second model was tested with course entered and held in block 1, and the remaining psychological variables from Table 2 entered stepwise in block 2. Agreeableness and the Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire were retained in the model, explaining 51% of the variance (p < 0.001). Table 3 presents data from patients with euphoria/disinhibition contrasted against the remaining sample. Note that the syndrome is somewhat more likely to occur in men and that patients with the syndrome are lower in agreeableness and somewhat lower in conscientiousness. Patient-informant discrepancies are higher in the euphoria/disinhibition patients, suggesting diminished insight in this subgroup. Patients with “high” euphoria/disinhibition scores were judged to be more cognitively impaired and to have more distressed caregivers.

DISCUSSION

Euphoria and associated neurobehavioral signs in MS have intrigued clinicians for over a century; but heretofore, the syndrome, originally called euphoria sclerotica27 had not been operationalized with objective criteria. We used the NPI to measure this construct in 75 consecutive, non-referred MS patients. This euphoria/disinhibition factor was present in 7% or 9% of the sample. These patients were characterized by secondary progressive course, low agreeableness on personality testing, poor insight, and impaired cognition. Caregivers of these patients were markedly distressed, suggesting that this syndrome has deleterious effects on caregiver-patient interactions. Ours is the first study to measure the prevalence of this syndrome in a consecutive, unselected clinical sample, using a valid and reliable psychometric test.

The euphoria/disinhibition factor captures not only euphoria, but other behaviors that have been associated with euphoria sclerotica such as disinhibition, impulsivility, and emotional lability.2,27,28,29 Several informants referred to distressing behaviors such as childishness, anger outbursts, and lack of empathy. Elevated euphoria/ disinhibition scores were also associated with low agreeableness which characterizes patients as impatient, inconsiderate, and quarrelsome. Altogether, these traits resemble the syndrome as described in the classic literature.1 The NPI does not include a measure of unawareness or, in the terms of Charcot, “indifference.” However, the NEO-PI provides an indirect measure of awareness by comparing self- and informant-reports of personality and behavioral tendencies. In healthy volunteers, these discrepancies were minimal. In our previous work,6 we found that patient/informant discrepancies were associated with executive function deficits in patients. To measure the original construct as described by Charcot, the NPI would have to be complemented by the NEO-PI or some similar measure that compares patient and informant reports of personality and behavior.

We propose that euphoria sclerotica as defined here is probably neuropsychologically mediated and caused by a combination of strategically located lesions and premorbid personality traits. The syndrome might be explained by white matter lesions causing disconnection of prefrontal cortex and limbic structures. Conversely, gray matter pathology is increasingly recognized in MS30 and focal pathology to inferior frontal cortex could also account for significant variance in this disorder. Studies investigating MRI correlates of the syndrome are underway.

This study is based on a consecutive series of non-referred patients and in our view, the results represent a reasonable estimate of the prevalence of this syndrome in MS clinic attendees. The frequency may be lower in a random, population based sample. A limitation of this study is the reliance upon informant-ratings. We view this as a necessary evil, given the impracticality of directly observing patients in their natural milieu. In the future, investigators may wish to validate this NPI construct with video recordings of staged social interactions. Validity data supporting the NPI and the NEO-PI notwithstanding, we should consider that factors other than a patient's behavior may influence informant ratings. An additional weakness of the study is its cross-sectional design, which does not allow for the study of emerging behavior change. A prospective, longitudinal study of these phenomena will be the natural next step in this research program.

These limitations aside, we conclude that abnormal behavior is common in MS and a syndrome characterized by euphoria, lability, and disinhibition and can be reliably detected using the NPI. We estimate the frequency of euphoria sclerotica to be 9%. The syndrome is associated with low agreeableness on personality measures, poor insight, cognitive impairment, and high levels of caregiver distress. Identification of this syndrome could impact favorably on the clinical care of MS patients via the development of new pharmacological treatments31 and counseling strategies for improving patient/caregiver interactions.32

|

|

|

1 Finger S: A happy state of mind. Archives of Neurology 1998; 55:241–250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Charcot JM: Lectures on the Diseases of the Nervous System. 1877Google Scholar

3 Rabins Peter V, Brooks Benjamin R, O’Donnell Pat, et al.: Structural brain correlates of emotional disorders in multiple sclerosis. Brain 1986; 109:585–597Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Rabins Peter V: Euphoria in Multiple Sclerosis. 1990; 180–185Google Scholar

5 Swirsky-Sacchetti, T, Mitchell, DR, Seward, J, et al.: Neuropsychological and structural brain lesions in multiple sclerosis: A regional analysis. Neurology 1992; 42:1291–1295Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Benedict RHB, Priore RL, Miller C, et al.: Personality disorder in MS correlates with cognitive impairment . Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2001; 13:70–76Link, Google Scholar

7 Costa PT, McCrae RR: NEO PI-R Professional Manual. Google Scholar

8 Digman JM: Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Anual Review of Psychology 1990; 41:417–440Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Digman JM: Higher-order factors of the Big Five. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 1997; 73:1246–1256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Goldberg Lewis R: The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist 1993; 48:26–34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Chatterjee A, Strauss ME, Smyth KA, et al.: Personality changes in Alzheimer's disease. Archives of Neurology 1992; 49:486–491Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Welleford EA, Harkins SW, Taylor, et al.: Personality change in dementia of the Alzheimer's type: Relations to Caregiver Personality and Burden. Experimental Aging Research 1995; 21:295–314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Cummings JL, Velazquez J, et al.: Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 1999; 11:51–57Link, Google Scholar

14 Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994; 44:2308–2314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al.: Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the international panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Annals of Neurology 2001; 50:121–127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, et al.: The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1996; 46:130–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Eysenck HJ: Personality and Individual Differences: A Natural Science ApproachGoogle Scholar

18 Goldberg LR: The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment 1992; 4:26–42Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Costa PT, McCrae RR: Professional Manual for the Revised NEO Personality Inventory and NEO Five-Factor Inventory. Google Scholar

20 Beck AT: Beck Depression Inventory. 1993Google Scholar

21 Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, et al: Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine 1994; 10:77–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, et al.: Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. Journal of Aging & Health 1993; 5:179–193Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Kurtzke JF: Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Annals of Neurology 1983; 13:227–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Benedict RHB, Munschauer FE, Linn R, et al.: Screening for multiple sclerosis cognitive impairment using a self-administered 15-item questionnaire. Multiple Sclerosis 2003; 9:95–101Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Kaufer Daniel I, Cummings JL, Christine D, et al.: Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Caregiver Distress Scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2–21–1998; 46:210–215Google Scholar

26 Wood Stacey A, Cummings JL, Barclay T, et al.: Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on distress in professional caregivers. Aging & Mental Health 8–24–1999; 3:241–245Google Scholar

27 Cottrell Samual Smith, Wilson SA Kinnier: The affective symptomatology of disseminated sclerosis. Journal of Neurology and Psychopathology 1926; 1–30Google Scholar

28 Brown Sanger, Davis Thomas K.: The mental symptoms of multiple sclerosis. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry 1922; 7:629–634Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Surridge David: An investigation into some psychiatric aspects of multiple sclerosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 1969; 115:749–764Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Bakshi R, Benedict RH, Bermel RA, et al.: Regional brain atrophy is associated with physical disability in multiple sclerosis: semiquantitative magnetic resonance imaging and relationship to clinical findings. Journal of Neuroimaging 2001; 11:129–136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Iannaccone S, Ferini-Strambi L: Pharmacologic treatment of emotional lability. Clinical Neuropharmacology 1996; 19:532–535Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Benedict RHB, Shapiro A, Priore RL, et al.: Neuropsychological counseling improves social behavior in cognitively-impaired multiple sclerosis patients. Multiple Sclerosis 2001; 6:391–396Crossref, Google Scholar