Cognitive Status of Psychiatric Patients Under Maintenance Electroconvulsive Therapy: A One-Year Longitudinal Study

Abstract

In recent years, maintenance electroconvulsive therapy (M-ECT) has been a common treatment within psychiatric practice. Little information is available regarding the cognitive risks of this treatment, however. In this study, twenty psychiatric outpatients were assessed during M-ECT and 1 year later on treatment. A comprehensive cognitive battery was administered, and a separate comparison group was used to calculate the Reliable Change Index. Global cognitive measures showed no significant difference in scores over time. Our results concur with those described in case reports and suggest that there is no significant association between cognitive decline and M-ECT.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has generally been used in patients with severe and medication-resistant psychiatric illness,1 but cognitive side effects present one major concern regarding this treatment.

The efficacy of ECT in depressive disorders is both well documented in the literature and supported by clinical experience.2,3 Although ECT is clearly most effective in mood disorders, it has also been shown to be an important treatment for those schizophrenic patients who do not respond to pharmacological treatment.4,5

However, ECT is typically discontinued once a response is achieved and patients who discontinue treatment after a course of ECT have high relapse rates.6 Sackeim et al.7 found that the relapse rate for depressed patients in virtual remission, within 6 months of discontinuing ECT and without any other active treatment, was 84%. Monotherapy with nortriptyline had limited efficacy (60% relapse rate), and the relapse rate was still high (39.1%), although its combination with lithium was more effective, particularly during the first month after finishing the ECT course.

Maintenance ECT (M-ECT) is considered to be an effective way of preventing relapses and recurrence in patients with major psychiatric disorders who have shown an initial response to ECT.8–12 Frequency of ECT sessions during M-ECT varies according to clinical requirements, usually weekly and at onset gradually decreasing from biweekly to monthly sessions. M-ECT is a recommended treatment for those patients with a recurrent illness that has been acutely responsive to ECT. Moreover, it is a safe and desirable option in some individuals, particularly drug-resistant patients13,14 or in medically compromised subjects who are sensitive to the toxic effects of certain medication.7 Additionally, M-ECT does not have any adverse physical effect other than those found in acute courses of ECT.15,16

Although M-ECT has been used more often in recent years, few studies have studied the adverse cognitive effects that might be associated with such treatment, and thus the risk of cognitive dysfunction following M-ECT remains unknown. Most reports on cases of acute ECT describe a transient memory dysfunction that disappears 3 to 6 months after the end of treatment.17 Other cognitive functions such as attention or frontal functions have not been widely studied, although they appear to be less affected than memory following an ECT course.18 Since the time between treatments is much longer during M-ECT, fewer cognitive side effects would be expected than during an acute course of ECT.

There is little research on the cognitive status of outpatients during M-ECT. Previous data seem to suggest that M-ECT is cognitively safe but are based on case reports,19–21 on retrospective studies without a comparison group,22 on subjective evaluations of cognitive dysfunction after treatment,23 or on global cognitive screening such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).24–27 Recently, Datto et al.28 used telephone assessments to evaluate the cognitive status of patients receiving M-ECT the day before the ECT session, the day after treatment, and 1 week later. Only one test, Verbal Fluency Category Test, which assesses language function, showed group level effects, with significant decrements of performance the day after an ECT treatment.

The aim of this present study was to determine the possible cognitive effects of a 1-year M-ECT treatment program. A comprehensive neuropsychological battery, which included measures of memory and attention and frontal functions, was used for the assessment.

METHODS

Subjects

Twenty-six outpatients treated with M-ECT in the psychiatric department of Barcelona's Hospital Clinic were recruited for an initial cognitive assessment. Dementia (taken as an MMSE score lower than 24) was an exclusion criterion. Only those patients who had no acute episodes of psychiatric illness during the year of the study and with whom the frequency of ECT sessions during this same period remained stable were selected. The frequency of sessions was adapted to the needs of each patient. At the time of the first neuropsychological assessment of the study, the mean intersession interval in the sample was 36.8 days (range=15–60 days). All of the patients finished their acute ECT course 6 months prior to assessment.

Twenty patients (76.9%) of the initial sample completed the longitudinal study and were reevaluated 1 year after the M-ECT treatment. Of the remaining six, five discontinued ECT treatment after total and stable remission of their psychiatric symptomatology, and one patient had a relapse during the year of the study and needed an acute course of ECT with three sessions per week. At retest, all these patients were receiving the same frequency of ECT treatments as at the time of baseline assessment (36.8 days) to avoid frequency interference in the cognitive outcome.

In terms of diagnosis, the patients who participated in the longitudinal study formed a heterogeneous group, as would be expected from clinical practice. Six patients were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, eight had recurrent depressive disorder, and six met criteria for schizophrenia. Each diagnosis was made by a trained psychiatrist (J.F.) using DSM-IV criteria and was confirmed independently by another psychiatrist experienced in the assessment of mood and schizophrenic disorders (M.B).

Ten psychiatric outpatients who had never been treated with ECT were selected in order to control for cognitive retest effects through calculation of the Reliable Change Index (RCI). This group consisted of one bipolar, two schizophrenic, and seven depressed patients.

Procedure

Informed consent was obtained after the procedure had been fully explained. Patients were treated with the standard bifrontotemporal electrode placement using a customized MECTA SR1 device (MECTA Corp, Lake Oswego, Ore). To be considered adequate, minimal seizure duration was 20 seconds of motor or 25 seconds of electroencephalogram manifestation. The seizure threshold was selected for each patient, and only one shock application was administered at each session over the course of year. Atropine, succinylcholine, and thiobarbital were the anesthetics used. Positive pressure ventilation with 100% oxygen was administered during the ECT treatment procedure.

All subjects were clinically and cognitively assessed. Electroconvulsive therapy patients were assessed before treatment on the day of the ECT session in order to ensure maximum intersession time. At retest, all patients were receiving the same frequency of ECT treatments as they were at the time of baseline assessment (36.8 days) in order to avoid temporal interference effects on cognitive state. Mood state was measured with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS).29 All patients had been in remission (HDRS score <8) during the first and second cognitive assessment and did not have any acute mood or psychotic episode for at least 3 months prior to the first neuropsychological assessment.

Although all patients were receiving pharmacological treatment during M-ECT, treatment did not vary significantly during the year of the study.

Cognitive Assessment

The neuropsychological test battery was administered by the same trained neuropsychologist (L.R.) in the same order to all patients. Global cognitive function was assessed by the MMSE.30 Short-term and long-term memory were evaluated with the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT).31 The Digits Forward test of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Adults (WAIS)32 was used to assess selective attention and the Trail Making Test, Part A33 was administered to evaluate simple motor velocity and attention. The Digit-Symbol Coding Test from the WAIS was used to determine visuomotor speed. Frontal functions were assessed by the Trail Making Test, Part B,33 the Tower of Hanoi34 and the Digits Backward Test, which measure mental flexibility, planning, and working memory, respectively. Verbal fluency, measured by the FAS Test,35 was also used as an indicator of frontal function. Available parallel forms of the memory tests (RAVLT versions) were used in order to minimize learning effect.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS for Windows V 10.0. We used a repeated measures analysis of variance (MANOVA) model, with the group variable as a between-subjects factor (experimental and healthy subjects) and using different cognitive measures at the first test as the repeated measure. Repeated measures analysis of variance (one factor: time of assessment) was used to compare cognitive scores of the first and second assessment 1 year later. The RCI was used to determine whether the test-retest change was statistically reliable. Reliable Change Index is necessary to analyze test-retest change in each subject of a sample in order to detect possible and relevant change in each individual. According to Maassen,36 classical test theory argues that an observed difference (Di) between test-retest scores can be split into a true difference and a component containing measurement error. The observed difference score is thus an unbiased estimator of the true difference. Under the null hypothesis that ECT treatment has no effect on cognitive functions, the RCI (Di/σED) (σED is the standard deviation (SD) of the difference in the control group) should not exceed a chosen critical value. In this study, RCI was established at ±1.96, in order to maintain the probability of committing a Type I error lower than 0.05.

RESULTS

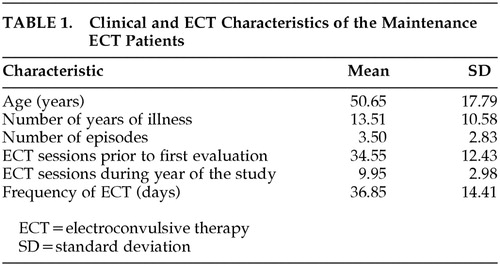

Twenty patients (15 women and five men) received M-ECT treatment for 1 year. The mean age was 50.6 years (SD=19.8, range=25–77). These patients differed with respect to the frequency of their ECT sessions and to the number of ECT sessions before baseline assessment. Table 1 shows the clinical and M-ECT variables for this group. The comparison group used to calculate the RCI was comprised of 10 psychiatric outpatients. The mean age of this group was 55.8 years (SD=16.2). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of age. With regard to clinical variables, there was no difference between the two groups in number of evolution years of the illness, otherwise difference in the number of acute episodes result significantly (t=3.4; p<0.002).

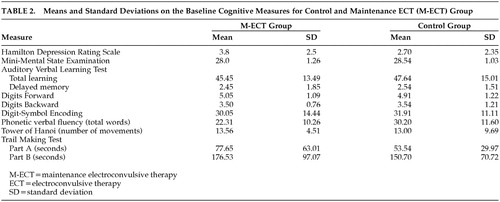

Regarding the cognitive variables during the first test, mixed model MANOVA found no significant interaction between groups by different cognitive measures (f=0.47; p=0.88), which indicates that the M-ECT patient group did not show a marked cognitive dysfunction in the first test session. Table 2 show means and standard deviations on the baseline cognitive measures for both groups.

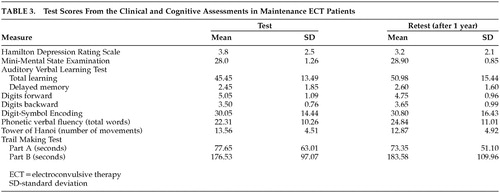

Multivariate analysis of variance demonstrated no significant difference in scores over time (F=0.852; p=0.62). None of the individual differences in test-retest scores reached significance. Test scores for the two cognitive assessments of the M-ECT patient group are shown in Table 3.

Neither treatment frequency, the clinical profile of subjects (number of years of illness and number of acute psychiatric episodes), or demographic variables (gender and age) showed a significant correlation with any of the cognitive scores.

Reliable Change Index values for all nine cognitive tests were calculated from the test-retest data of the comparison group in order to determine whether the cognitive change observed in the M-ECT patient group was significantly different.

Applying the RCI to the 20 M-ECT patients on the nine cognitive tests produced a total of 180 values. Only six scores were found to be situated below what is considered the normal interval (–1.96 to 1.96), and 13 were situated above this interval. The remainder did not reach a significant test-retest difference. The significant RCI values obtained for each cognitive measure are described below.

Immediate and Working Memory

All of the M-ECT subjects obtained RCI values between –1.96 and 1.96 on the Digits Forward and Backward of the WAIS-III. None of the changes was significant.

Encoding and Retrieval of New Information

Taking into account the confidence intervals used in the RCI, with respect to total learning and delayed memory of the RAVLT, five subjects improved (RCI=2.73; 3.63; 4.48; 2.88; 7.91); the performance of one deteriorated (RCI=–2.99); and 14 were unchanged on retest declarative memory measures.

Verbal Phonetic Fluency

Applying the RCI to verbal fluency, one subject obtained significantly lower scores on the retest measures (RCI=–4.46), and two subjects significantly improved after 1 year of M-ECT treatment (RCI=2.77; 2.77). The rest of the sample remained unchanged.

Attention and Cognitive Flexibility

Estimating the RCI for the Trail Making Test, Part A, four subjects were found to have significantly lower measures (RCI=–9.41; –2.40; –2.84; –4.53), and two had significantly higher (RCI=1.87; 6.22; 3.64). In the case of the Trail Making Test, part B, one subject was situated above the normal interval (RCI=3.27). None of the subjects obtained scores below the normal interval.

DISCUSSION

Psychiatric patients showed no adverse cognitive effects after 1 year of M-ECT treatment. There were no significant differences 1 year following M-ECT treatment on measures of memory and attention and frontal functions. This finding supports the hypothesis that the greater time between ECT treatments leads to fewer cognitive side effects than would be expected with an acute course of ECT. Cognitive dysfunction during ECT is thought to be due to electrochemical effects on the medial temporal lobe, although the specific mechanism remains unclear. Several explanations have been proposed for the transient cognitive dysfunction found after an acute course of continuous ECT: 1) an abnormal long-term potentiation mechanism; 2) excessive release of excitatory amino acids and the activation of their receptors, such as N-methyl-D-aspartate; 3) decreased cholinergic transmission; 4) increased cerebral blood pressure; and 5) reductions in regional cerebral blood flow.17 A greater interval between ECT sessions probably enables the neurobiological bases to recover, and the better cognitive tolerability of M-ECT would therefore derive from the absence of the cumulative effect produced when sessions are given within a short period, as is the case of acute treatment, which would explain why we found no significant decreases on any of the cognitive functions evaluated.

Datto et al.28 found no memory or attention deficits in a sample of 31 patients receiving M-ECT, either before or after an ECT session. However, their study is limited to the absence of any mental state examination of the sample and due to the use of telephone assessments. Longitudinal studies of the efficacy of M-ECT using global cognitive measures have not found any significant decreases on the MMSE.24–27 Furthermore, Vanelle et al.23 found no significant subjective memory complaints in patients undergoing M-ECT treatment. The results obtained in single-case reports also indicate the absence of any significant association between cognitive decline and M-ECT.19–21,37 In this study, we have intended to improve some design limitations of previous studies, and our results indicate that there is not a significant cognitive dysfunction associated with M-ECT.

Maintenance electrotherapy patients form a specific psychiatric group characterized by severe illness that is often resistant to pharmacological treatment. As such, it is very difficult to find a comparison group to match them. We assessed a group of psychiatric patients who had never been treated with ECT, and we used the RCI statistical method to control for test-retest reliability. This enabled us to determine when a change in test performance exceeded a value that could be explained on the basis of practice effects or other sources of measurement error that could not be controlled for. In analyzing the RCI obtained for all the cognitive measures of our sample, only six out of 180 values were outside of the RCI values considered normal interval.

Another limitation to this study was the absence of a cognitive assessment prior to beginning ECT treatment. The sample in question had already been treated with ECT prior to the first cognitive assessment. However, the absence of significant group differences at baseline status may indicate that there was not a significant cognitive dysfunction associated with previous ECT sessions in the M-ECT group. For this reason, our results only provide information about the cognitive functions during 1 year of M-ECT treatment.

Further longitudinal studies that include cognitive measures taken before ECT treatment begins must be conducted. Although this would, however, yield another methodological limitation: the interference of psychiatric symptomatology in pretreatment data. In our design, controlling the psychiatric stability of all the M-ECT patients almost 3 months before each cognitive assessment solved this methodological problem.

In spite of the design limitations, we consider our results to have significant clinical implications. Presently, most M-ECT studies are based on clinical efficacy. Further studies that carry out cognitive assessment during the period of M-ECT are, therefore, necessary in order to support the cognitive safety of this treatment and, consequently, to determine the quality of life and everyday functioning of patients during ambulatory ECT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially supported by TDOC grant (2001-00001) from the Generalitat de Catalunya. The authors thank the staff of the Psychiatric Day Hospital of Barcelona's Hospital Clinic for all their support.

This study was conducted at the University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, Department of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychobiology.

|

|

|

1 Ciapparelli A, Dell'Osso L, Tundo A, et al.: Electroconvulsive therapy in medication-nonresponsive patients with mixed mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:552–555Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Philibert RA, Richards L, Lynch CF, et al.: Effect of ECT on mortality and clinical outcome in geriatric unipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:390–394Medline, Google Scholar

3 Parker G, Roy K, Wilhelm K, et al.: Assessing the comparative effectiveness of antidepressant therapies: a prospective clinical practice study. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:117–125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Fink M, Sackeim HA: Convulsive therapy in schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:27–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 The Practice of Electroconvulsive Therapy: Recommendations for Treatment, Training, and Privileging: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association, 2nd ed. Washington, DC, APA, 2001Google Scholar

6 Lauritzen L, Odgaard K, Clemmesen L, et al.: Relapse prevention by means of paroxetine in ECT-treated patients with major depression: a comparison with imipramine and placebo in medium-term continuation therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 94:241–251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Sackeim HA, Haskett RF, Mulsant BH, et al: Continuation pharmacotherapy in the prevention of relapse following electroconvulsive therapy: a randomized controlled study. JAMA 2001; 285:1299–1307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Petrides G, Dhossche D, Fink M, et al.: Continuation ECT: relapse prevention in affective disorders. Convuls Ther 1994; 10:189–194Medline, Google Scholar

9 Lohr WD, Figiel GS, Hudziak JJ, et al.: Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:217–218Medline, Google Scholar

10 Hirschfeld RMA, Keller MB, Panico S, et al.: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277:333–340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Judd LL: The clinical course of unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:989–991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Fredman S, Rosenbaum JF: Recurrent depression, resistant clinician? Harv Rev Psychiatry 1998; 5:281–285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Rabheru K, Persad E: A review of continuation and maintenance electroconvulsive therapy. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42:476–484Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Tew J, Mulsant B, Haskett R, et al: Acute efficacy of ECT in the treatment of major depression in the old-old. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1865–1870Medline, Google Scholar

15 Jaffe R, Dubin W, Shoyer B, et al.: Outpatient electroconvulsive therapy: efficacy and safety. Convuls Ther 1990; 6:231–238Medline, Google Scholar

16 Fink M, Abrams R, Bailine S, et al.: Ambulatory electroconvulsive therapy: report of a task force of the Association for Convulsive Therapy. Convuls Ther 1996; 12:42–55Medline, Google Scholar

17 Rami-González L, Bernardo M, Boget T, et al.: Subtypes of memory dysfunction associated with electroconvulsive therapy: characteristics and neurobiological bases involved. J ECT 2001; 17:129–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Calev A, Gaudino EA, Squires NK, et al.: ECT and non-memory cognition: a review. Br J Clin Psychol 1995; 34:505–515Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Grunhaus L, Pande AC, Hasket RF: Full and abbreviated courses of maintenance electroconvulsive therapy. Convuls Ther 1990; 6:130–138Medline, Google Scholar

20 Devanand DP, Verma AK, Tirumalasetti F, Sackeim HA: Absence of cognitive impairment after more than 100 lifetime ECT treatments. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:929–932Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Barnes RC, Hussein A, Anderson D, et al.: Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy and cognitive function. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:285–287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Brodaty H, Hickie I, Mason C, et al.: A prospective follow-up study of ECT outcome in older depressed patients. J Affect Disord 2000; 60:101–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Vanelle JM, Loo H, Galinowski A, et al.: Maintenance ECT in intractable manic depressive disorders. Convuls Ther 1994; 10:195–205Medline, Google Scholar

24 Thienhaus OL, Margletta S, Bennet J, et al.: A study of the clinical efficacy of maintenance ECT. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51:141–144Medline, Google Scholar

25 Chanpattana W, Chakrabhand ML, Sackeim HA, et al.: Continuation ECT in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a controlled study. J ECT 1999; 15:178–192Medline, Google Scholar

26 Chanpattana W, Chakrabhand ML: Factors influencing treatment frequency of continuation ECT in schizophrenia. J ECT 2001; 17:190–194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Chanpattana W, Chakrabhand ML: Combined ECT and neuroleptic therapy in treatment refractory schizophrenia: prediction of outcome. Psychiatry Res 2001; 105:107–115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Datto CJ, Levy S, Miller DS, et al.: Impact of maintenance ECT on concentration and memory. J ECT 2001; 17:170–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale of primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Rey A: En l'Examen clinique en psychologie. Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1964Google Scholar

32 Wechsler DA: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Adults (WAIS). New York, Psychological Corp, 1955Google Scholar

33 Army Individual Test Battery: Manual of Directions and Scoring. Washington, DC, War Department, Adjutant General's Office, 1964Google Scholar

34 Goldberg TE, Saint-Cyr JA, Weinberger DR: Assessment of procedural learning and problem-solving in schizophrenic patients by Tower of Hanoi tasks. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1990; 2:165–173Link, Google Scholar

35 Borkowski JG, Benton AL, Spreen O: Word fluency and brain damage. Neuropsychologia 1967; 5:135–140Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Maassen GH: Principles of defining reliable change indices. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2000; 22:622–632Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Fox HA: Extended continuation and maintenance ECT for long-lasting episodes of major depression. J ECT 2001; 17; 60–64Google Scholar