Cognitive Impairment Associated With Major Depression Following Mild and Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury

Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) and major depression are neuropsychiatric conditions that have been associated with cognitive dysfunction. The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between major depression and cognitive impairment following mild and moderate TBI. Seventy-four TBI patients were assessed for the presence of major depression using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV and completed a neurocognitive assessment battery. Subjects with major depression (28.4%), compared to those without, were found to have significantly lower scores on measures of working memory, processing speed, verbal memory and executive function. Potential mechanisms and implications for treatment are discussed.

Major depression may be a particularly important factor influencing outcome following traumatic brain injury (TBI). With a point prevalence of between 14% and 29%,1–3 major depression is a relatively common complication of TBI that is associated with psychosocial dysfunction1–4 and postconcussional symptoms.1,4

Cognitive sequelae are among the most disabling of postconcussional symptoms following TBI5 and typically contribute more to persisting disability than physical impairment.6 Following TBI, deficits are consistently demonstrated in the domains of attention,7 memory,8,9 and executive functioning.10,11

The common, prominent, and often reversible cognitive dysfunction associated with major depression in populations unaffected by TBI has long been recognized.12 Executive dysfunction is the most consistently demonstrated deficit across studies of patients with major depression.13 Despite some variability, many studies have also demonstrated significant attentional13 and memory14 deficits in those with major depression compared with nondepressed control subjects.

Because of the high costs associated with disability in TBI,15 it is becoming increasingly important to identify markers of poor outcome. Major depression is a highly treatable disorder,16 and cognitive deficits are often remediated with improvement in mood.14

The aim of the present study was to explore the relationship between major depression and cognition following mild and moderate TBI. We hypothesized that depressed TBI patients would have greater deficits in attention, memory, and executive functioning than nondepressed patients.

METHODS

Patient Selection

A sample of 74 patients attending a TBI clinic in a large general hospital was assessed for the presence of major depression and cognitive deficits. Subjects were under the age of 65 and sustained a nonpenetrating mild or moderate TBI. Mild TBI was defined by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine: loss or alteration of consciousness at the time of injury for 30 minutes or less, an initial Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13–15, and posttraumatic amnesia of less than 24 hours.17 Subjects with moderate TBI had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 9–12 and a posttraumatic amnesia of less than 1 week.18 Exclusion criteria included a premorbid history of focal brain disease (e.g., stroke, tumor), serious medical illness (e.g., acute heart or renal failure, malignancy) and a history of dementia, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder. All subjects provided informed consent.

Data Collection

Demographic, prior health, and injury data.

These were collected from a clinical review of the trauma chart and discussion with the patient (and informant, where available). Information gathered included age, gender, marital status, educational history, prior medical history, use of alcohol and other substances, family psychiatric history, and prior diagnosis of mood disorder. Injury data, including the mechanism of accident, duration of loss of consciousness, initial Glasgow Coma Scale score in the emergency room, duration of posttraumatic amnesia,19 the presence of other musculoskeletal injuries, and brain CT scan results, was also recorded.

Assessment of major depression.

Subjects were assessed by a psychiatrist (who was blind to the cognitive data) for the presence of a major depressive episode using the depression module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID).20 DSM criteria are considered reliable and valid in TBI samples.21

Cognitive measures.

Attention/working memory and processing speed were assessed using the working memory and processing speed subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 3rd ed.22 Memory was assessed using the logical memory test (story two—delayed) of the Wechsler Memory Scale, 3rd ed.,22 as well as the California Verbal Learning Test (total and long delay free recall),23 and the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test—Revised.24 Executive functioning was assessed with the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test25—total number of categories completed and perseverative responses. Finally, the vocabulary subscale of the Wechsler Abbreviated Intelligence Scale26 was used as an estimate of premorbid intelligence. For the neurocognitive tests, the raw data was analyzed. Subsequently a post hoc analysis was done defining “impairment” as a score below the ninth percentile for age and education on the individual cognitive variables (with the exception being below the 11th percentile for age and education on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test total). These cutoffs were applied since (by convention) scores below this would be typically considered within the borderline impaired to impaired range and correspond to scores of more than one and one-half or two standard deviations below the mean.

Statistical Analyses

Patients with and without major depression were compared using the chi-square statistic (or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate) for categorical demographic, prior health and injury variables. Age, length of time postinjury and the continuous cognitive outcome variables were compared between groups using analysis of variance. A Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons: With eight outcome variables (working memory, processing speed, Wechsler Memory Scale, 3rd ed., logical memory, California Verbal Learning Test total and long delay free recall, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test—Revised total, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test total and perseverative responses), the critical p value is 0.006 (i.e., 0.05/8). Nonsignificant trends were reported provided that a critical value of p<0.05 was obtained. The potentially confounding effect of demographic mismatch between groups was controlled for using analysis of covariance, using the same critical p value of 0.006. A categorical analysis was conducted, using chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate, in order to compare the proportion of subjects in each group who would be classified as “impaired” on the various cognitive tests. Post hoc comparisons of the cognitive performance of those with and without a past history of depression, substance misuse, and alcohol misuse were conducted.

RESULTS

Demographics

Subjects were on average 34.89 years of age (SD=13.11, range=18–64) and were tested at a mean of 200.43 days following their injury (SD=49.5, range=122–467). With regard to past psychiatric problems, eight (10.8%) had a previous history of depression, 10 (13.5%) had a significant history of alcohol misuse, and 12 (16.2%) had a history of substance misuse.

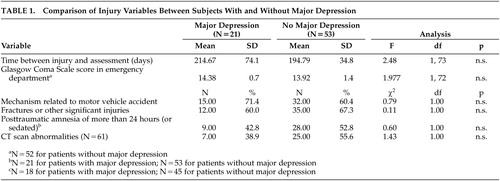

Major Depression

Based on the SCID, 21 patients (28.4%) met criteria for major depression. Subjects with major depression were older (mean=41.38 years, SD=13.2) than those without (mean=32.32, SD=12.2) (F=7.90, df=1, 73, p<0.01), and more likely to have a past history of depression (23.8% versus 5.6%) (χ2=5.14, df=1, p<0.05). However, there were no differences between groups in gender, education, marital status, employment, previous TBI, premorbid intelligence, family psychiatric history or past substance or alcohol use. There were no differences between groups in the mechanism of injury, associated other injuries, CT scan abnormalities, Glasgow Coma Scale scores, or duration of posttraumatic amnesia (Table 1).

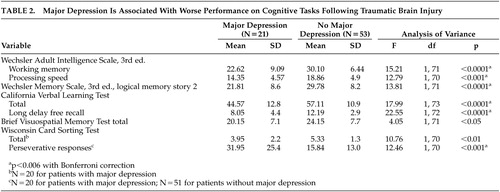

Major Depression and Cognition

Subjects with major depression had scores indicative of significantly poorer functioning on the measures of working memory, processing speed, and verbal memory. There was a trend toward poorer performance on the visual memory task (Brief Visuospatial Memory Test—Revised) (p<0.05). Subjects with major depression had significantly more perseverative responses on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and a trend toward poorer overall performance on this measure of executive dysfunction (p<0.01) (Table 2). These findings remained significant after controlling for age and past history of depression.

Based on the established percentile cutoffs, only 15% of the depressed group were not classified as “impaired” on any of the cognitive measures, while 52.8% of the nondepressed patients were unimpaired (p=0.004, Fisher’s exact test). Significantly more participants with major depression were categorized as “impaired” on working memory (35.0% versus 3.8%) (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test) and processing speed (45.0% versus 5.9%) (p<0.0001, Fisher’s exact test). There were nonsignificant trends for patients with depression to be more likely “impaired” on the verbal memory tasks and on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test total categories completed.

Comparisons of subjects with and without a past history of depression, substance misuse, and alcohol misuse yielded no differences on any cognitive task.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that at 6 months following mild and moderate TBI, major depression is associated with worse performance across an array of cognitive domains including attention, memory, and executive functioning. While more than one-half of the patients without major depression were unimpaired on any cognitive test, this was true for only 15% of the patients with major depression. These findings are consistent with the studies demonstrating cognitive deficits in the primary major depression literature. Although other studies have previously shown an association between depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment in TBI,27–31 in those studies formal clinical examination for the presence of DSM-defined major depression was lacking, and self-report27–30 or clinical rating instruments of depression31 were used. Levin et al.32 have recently demonstrated worse performance on cognitive tasks in patients with SCID-defined major depression. However, in that study, subjects with general trauma as well as those with TBI were combined, and data on categorical “impairment” was not presented. Furthermore, the prevalence of major depression postinjury in that study was only 12%, which is lower than previously established rates in the literature.2,3

In the present study, between-group differences in the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and Brief Visuospatial Memory Test—Revised may have been obscured by the conservative Bonferroni correction, the restricted range of possible scores on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test total categories, and a “ceiling effect” for the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test—Revised.

Traumatic brain injury has a strong predilection for involvement of the anterior temporal and frontal lobes,33,34 and this is likely the reason for prominent memory and executive dysfunction seen following TBI.5 Similarly neuroimaging studies of primary major depression have demonstrated functional abnormalities in the frontal and subcortical limbic regions.35 With this shared neurobiological substrate, cognitive deficits present by virtue of TBI alone seem to be particularly magnified with the development of major depression. In order to understand this relationship further, studies incorporating depressed non-TBI control subjects are needed, as well as imaging studies of mood and cognition in TBI patients.

Major depression following TBI can readily respond to treatment, and there is indication that aspects of cognition may also improve with successful antidepressant treatment in this population.36 Since depression has a strong influence on cognitive dysfunction post-TBI, antidepressant therapy presents a potentially useful adjuvant to rehabilitation. It has the potential to substantially improve quality of life by addressing two significant sources of morbidity following TBI—namely, mood and cognitive dysfunction. This may ultimately translate into a reduced economic burden of TBI by allowing patients to return to work and resume a productive life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Feinstein is supported by funding from the Canadian Institute for Health Research. Drs. Rapoport and Feinstein are supported by an operating grant from the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation. The results and conclusions are those of the authors. The authors would like to thank Alison Jardine, Vicky Pelchat, and Andrea Phillips for their assistance with this research.

|

|

1 Rapoport M, McCullagh S, Streiner D, et al: The clinical significance of major depression following mild traumatic brain injury. Psychosomatics 2003; 44:33–37Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Arndt SV, et al: Depression following traumatic brain injury: a 1 year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 1993; 27:233–243Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Gomez-Hernandez R, Max JE, Kosier T, et al: Social impairment and depression after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997; 78:1321–1326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Fann JR, Katon WJ, Uomoto JM, et al: Psychiatric disorders and functional disability in outpatients with traumatic brain injuries. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1493–1499Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 McCullagh S, Feinstein M: Cognitive impairment, in Textbook of Traumatic Brain Injury. Edited by Silver JM, McAllistar TW, Yudofsky SC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2004, pp 321–336Google Scholar

6 Brooks N, McKinlay W, Symington C, et al: Return to work within the first seven years of severe head injury. Brain Inj 1987; 1:5–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Niemann H, Ruff RM, Kramer JH: An attempt toward differentiating attentional deficits in traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rev 1996; 6:11–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Richardson JTE: Clinical and Neuropsychological Aspects of Closed Head Injury. East Sussex, UK, Psychology Press, 2000, pp 97–124, 146–156Google Scholar

9 Wiegner S, Donders J: Performance on the California Verbal Learning Test after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1999; 21:159–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Stuss DT, Ely P, Hugenholtz H, et al: Subtle neuropsychological deficits in patients with good recovery after closed head injury. Neurosurgery 1985; 17:41–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Brooks J, Fos LA, Greve KW, et al: Assessment of executive function in patients with mild traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 1999; 46:159–163Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Kilogh L: Pseudodementia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1961; 37:336–351Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Ottowitz W, Dougherty D, Savage C: The neural network basis for abnormalities of attention and executive function in major depressive disorder: implications for application of the medical disease model to psychiatric disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2002; 10:86–99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Burt DB, Zembar M, Niederehe G: Depression and memory impairment: a meta-analysis of the association, its pattern and specificity. Psychol Bull 1995; 117:285–305Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Feinstein A, Rapoport M: Mild traumatic brain injury: the silent epidemic. Can J Public Health 2000; 91:325–326, 332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:971–983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Kay T, Harrington DE, Adams R, et al: Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1993; 8:86–87Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Dikmen SS, Levin HS: Methodological issues in the study of mild head injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1993; 8:30–37Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Russell W, Smith A: Post traumatic amnesia after closed head injury. Arch Neurol 1961; 5:16–29Crossref, Google Scholar

20 First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Research Version (SCID-I). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

21 Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Arndt S: Are there symptoms that are specific for depressed mood in patients with traumatic brain injury? J Nerv Ment Dis 1993; 181:91–99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale: Technical Manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp (Harcourt), 1997Google Scholar

23 Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, et al: The California Verbal Learning Test Manual. New York, Psychological Corp, 1987Google Scholar

24 Benedict R: Brief Visuospatial Memory Test—Revised. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1997Google Scholar

25 Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, et al: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1993Google Scholar

26 Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp (Harcourt), 1999Google Scholar

27 Gfeller JD, Chibnall JT, Duckro PN: Postconcussion symptoms and cognitive functioning in posttraumatic headache patients. Headache 1994; 34:503–507Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Attenberry-Bennett J, Barth J, Lloyd B, et al: The relationship between behavior and cognitive defects, demographics and depression in patients with minor head injuries. Int J Clin Neuropsychol 1986; 8:114–117Google Scholar

29 Bornstein R, Miller H, Van Schoor J: Neuropsychological deficit and emotional disturbance in head-injured patients. J Neurosurg 1989; 70:509–513Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Satz P, Forney DL, Zaucha K, et al: Depression, cognition, and functional correlates of recovery outcome after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 1998; 12:537–553Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Rapoport M, McCauley S, Levin H, et al: The role of injury severity in neurobehavioral outcome 3 months after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2002; 15:123–132Medline, Google Scholar

32 Levin HS, Brown SA, Song JX, et al: Depression and posttraumatic stress disorder at three months after mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2001; 23:754–769Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Levin HS, Williams DH, Eisenberg HM, et al: Serial MRI and neurobehavioural findings after mild to moderate closed head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992; 55:255–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Gentry LR, Godersky JC, Thompson B: MR imaging of head trauma: review of the distribution and radiopathologic features of traumatic lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1988; 150:663–672Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Mayberg HS: Modulating limbic-cortical circuits in depression: targets of antidepressant treatments. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 2002; 7:255–268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 Fann JR, Uomoto JM, Katon WJ: Cognitive improvement with treatment of depression following mild traumatic brain injury. Psychosomatics 2001; 42:48–54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar