Awareness of Illness in Schizophrenia: Associations With Multiple Assessments of Executive Function

Presently, a consensus is emerging that some forms of poor insight in schizophrenia, particularly in post-acute phases of illness, reflect cognitive deficits which limit one’s ability to grasp and create a coherent narrative about complex aspects of their disorders. 8 In other words, perhaps they are unaware they are ill because of difficulties making sense of and framing the enormous complexities posed by the dilemmas of schizophrenia. Most promising are findings that performance on tests of one domain of executive function, flexibility of abstract thought, predicts insight. It has been suggested, for instance, that people with schizophrenia who deny that they are ill perform more poorly relative to people with schizophrenia who acknowledge their condition on neurocognitive tests requiring them to produce novel and flexible solutions to complex problems. 9 – 13 Deficits in this domain of executive function have also been linked to graver difficulties coherently representing psychiatric disabilities in transcribed narratives elicited in an unstructured interview. 14 Other literature supporting this view includes observations that unawareness of illness appears to be similar to unawareness of neurological illness, sometimes called anosognosia which is linked to impairments in executive function, 15 as well as studies linking awareness of illness, medication adherence, and executive function. 16

Limitations of this literature, however, include the measurement of abstract flexibility generally using only one measure, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, and measurement of insight as a one-dimensional phenomenon. It is thus unclear what qualities of flexibility of abstract thought are most closely linked to which domains of insight. Although some evidence suggests executive function is most strongly linked to the labeling of psychotic experiences as symptoms, 9 , 14 it is unclear what aspects of flexible abstract thinking are related to what kinds of difficulties with awareness.

Using a battery of recently redesigned tests, we examined associations between measures of three domains of insight (awareness of symptoms, treatment need, and consequences of illness) while assessing different dimensions of flexibility of abstract thought and executive function. We predicted that poorer performance on these tests would be linked with lesser insight across all three insight domains. We considered the correlations between different executive function measures and insight to be exploratory in nature. To rule out the possibility that any association between awareness of disorder and neurocognition was the result merely of greater levels of symptoms, we also assessed four different domains of psychopathology.

METHOD

Participants

Forty-eight men and five women with DSM-IV diagnoses of schizophrenia (N=29) or schizoaffective disorder (N=24) were recruited from outpatient psychiatry clinics at a VA Medical Center and community mental health center. Mean age was 47.51 (SD=9.12) years and mean education was 12.85 (SD=1.80) years. Participants had a mean of 9.06 (SD=9.45) lifetime hospitalizations with the first occurring on average at age 24.86 (SD=7.19). Twenty-eight participants were Caucasian, 23 were African-American, and two were Latino. All were in a post-acute phase of illness defined by not having hospitalizations or changes in medication in the prior month. Exclusion criteria included mental retardation or active substance abuse.

Instruments

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) 17 is a 30-item rating scale completed by clinically trained research staff at the conclusion of chart review and a semistructured interview. It is one of the most widely used semistructured interviews for assessing the broad range of psychopathology in schizophrenia. For the purposes of this study, we utilized four of the analytically derived PANSS factor component scores: positive, negative, excitement, and emotional discomfort. 18 Assessment of interrater reliability for raters in this study was in the excellent to good range, with intraclass correlations ranging from 0.80 to 0.93.

The Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD) 1 is a rating scale completed by clinically trained research staff following a semistructured interview and chart review. For the purposes of this study we used the three central items of the SUMD: 1) awareness of mental disorder; 2) awareness of the consequences of mental disorder; and 3) awareness of the effects of treatment. Each of these items is rated on a five point scale, with 1 being complete awareness and 5 being severe unawareness. Assessment of interrater reliability for raters in this study was in the excellent to good range with intraclass correlations ranging from 0.82 to 0.91.

The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) 19 is a battery of traditional executive function tests designed to comprehensively assess key facets of higher order thinking believed to be mediated primarily by the frontal lobes of the brain. For instance, familiar tests, such as the Trails and Stroop tests, were revised to maximize demands on executive function. To minimize the chances of a spurious finding, one score from each of six D-KEFS subtests was chosen for analysis, and two-tailed tests of significance were employed, despite unidirectional hypotheses. The D-KEFS scores employed were: a) Letter-Number Switching on Trail-Making, or time taken to alternately connect numbers with letters on a test booklet; b) Category-Switching on Verbal Fluency Task, or how many words from alternating categories could be produced verbally in 60 seconds; c) Inhibition-Switching from the Color-Word Task, or the capacity to alternately name the color of the ink a word is printed in (which spells out a different color) and then read the word, ignoring the color it is printed in; d) correct sorts from the Sorting Task or the number of different ways participants arrange cards into two groups based on the cards’ attributes; e) total achievement score on the Tower Task or performance on trials of increasing complexity that ask participants to build towers by moving up to five differing-sized donuts one at a time across three prongs; and f) total score for the Word Context Task which assesses how quickly the meaning of nonsense words is grasped from contextual hints.

Procedures

The appropriate research review committees of Indiana University and the Roudebush VA Medical Center approved all procedures. Following informed consent, diagnoses were determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). 20 A clinical psychologist (PL or LD) conducted all diagnostic interviews. Following the SCID, participants were administered the PANSS, SUMD and D-KEFS. PANSS and SUMD raters were blind to D-KEFS scores. Neurocognitive testing and PANSS interviews were conducted by trained research assistants with a minimum of a Bachelor’s degree in psychology or a related field.

RESULTS

Means and standard deviations for SUMD subscales were: Awareness of Illness: 2.5 (1.39); Treatment Need: 2.3 (1.0); and Consequences of Illness: 2.7 (1.26). Means and standard deviations for D-KEFS scaled scores were: Trail-Making Letter-Number Switching: 5.60 (4.20); Verbal Fluency Category-Switching: 6.60 (3.15); Color-Word Inhibition-Switching; Sorting Task correct sorts: 7.94 (3.50); Tower Achievement: 8.57 (3.70); Word Context: 6.19 (3.70). SUMD scores were not significantly related to age, education, lifetime hospitalizations, or diagnosis. D-KEFS scores did not differ between participants with schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia.

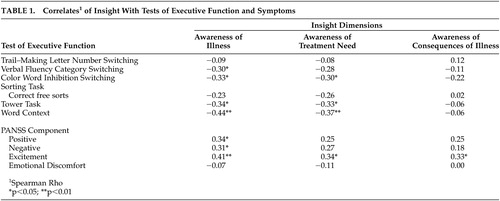

Because SUMD scores are ordinal and not necessarily normally distributed, Spearman Rho coefficients were computed to determine if they were related to D-KEFS and PANSS scores. As revealed in Table 1 , Awareness of Illness was related to Verbal Fluency, Color-Word, Tower and Word Context scores. Awareness of Treatment Need was related to Color-Word, Tower and Word Context scores. Awareness of Illness Consequences was not significantly related to D-KEFS tasks. Since awareness of illness and treatment needs were related to multiple symptom and D-KEFS scores, stepwise multiple regressions were conducted in which PANSS component scores were entered first as covariates to predict awareness of symptoms and treatment needs. Two significant predictor equations were produced: F (5, 46)=5.82, p<0.001; F (3, 48)=5.30, p<0.01, respectively. Awareness of Illness was significantly predicted by Excitement symptoms (R 2 =0.16), Tower Achievement (R 2 =0.13) and Color-Word Inhibition-Switching (R 2 =0.05). For Awareness of Treatment Need, Excitement (R 2 =0.14) and the Tower Achievement (R 2 =0.11) were significant contributors.

|

DISCUSSION

Results are consistent with previous studies linking unawareness of schizophrenia to deficits in flexibility of abstract thought. Performance on tasks requiring participants to produce words from alternating categories (Verbal Fluency task), to attend alternately to different qualities of a stimulus (Color Word task), to plan ahead visually and spatially (Tower task), and to grasp meaning with an evolving context (Word Context task) each predicted less awareness of illness. Performance on tasks requiring participants to attend alternately to different qualities of a stimulus (Color Word task), to plan ahead visually and spatially (Tower task), and to grasp meaning with an evolving verbal context (Word Context task) predicted less awareness of treatment need. Awareness of the consequences of illness was not related to neurocognitive test performance. When entered into a multiple regression model controlling for symptom level, ability to plan ahead visually and spatially and to attend alternately to different qualities of a stimulus were uniquely related to awareness of illness, accounting for 18% of the variance. When entered into a second multiple regression also controlling for symptoms level, the ability to plan ahead visually and spatially was uniquely related to awareness of treatment, accounting for an additional 11% of the variance.

Though causality cannot be determined in such a cross-sectional design, results may suggest speculations which could guide future research. For one, it is possible that unawareness of illness and treatment need may, in part, develop as a result of difficulties alternating attention between visual or verbal categories, planning action sequences requiring multiple steps, hypothesis testing, and employing deductive reasoning in tasks where progress is incremental. Of note, the lack of a relationship between insight and the Trails task may suggest that lack of insight is not related merely to problems shifting set between similar categories on nonverbal tasks within a given time frame. Making sense of psychotic experiences may be more affected by compromises in the ability to produce fluid responses to situations that call for the moving back and forth between disparate concepts and/or task demands. Intuitively these deficits could make it difficult for someone to both think about a troubling experience as it happened immediately (e.g., a hallucination) and then, in an act of metacognition, consider it in more depth, stepping outside of the moment and examining one’s own thoughts and feelings from the view of others (e.g., how might a close friend think about this). Without being able to develop an idea of how someone else might see this problem, it might be even more difficult to next think about what kinds of assistance could be helpful. Additionally, beyond being associated with the capacity to flexibly shift set, the Color Word and Tower tasks both tap inhibition, another domain of executive function. It is thus possible to speculate that with poor inhibition there may be poorer self-monitoring skills among some persons with schizophrenia, resulting in less awareness.

There are rival hypotheses that cannot be ruled out. It remains possible, for instance, that insight can be equally affected by any of a number of qualities of executive function, that insight affects neurocognition or that any relationships observed in our data are the result of other factors not assessed here. It is also possible that cognitive function affects insight through an interaction with societal factors, such as stigma and economic disadvantage, which could also influence the formation or lack of formation of an account of the disorders of schizophrenia.

There were several unexpected findings. First, it was surprising that Excitement symptoms on the PANSS were related to all three facets of insight and that that relationship did not wholly obscure the associations of insight with neurocognition. One speculation for the purposes of future study is that for some, being in a state of arousal either left them unable to think about their dilemmas effectively or they felt too vulnerable to acknowledge any deficits and so denial seemed more adaptive to them. It is also possible that poor insight, as noted above, was the result of deficits in inhibition as well. Deficits in cognitive inhibition might explain heightened levels of Excitement on the PANSS, which includes measures of difficulty with behavioral and affect regulation.

It was also unexpected that consequences of illness would be unrelated to any neurocognitive score. This may suggest that more global appraisals of the dilemmas of mental illness are less a matter of higher order reasoning. It is additionally interesting that while much previous literature has linked insight to the Wisconsin Card Sort Test (WCST), 9 – 13 insight was not linked to the D-KEFS sorting test. One difference between the D-KEFS and WCST is that the WCST requires set-shifting at unexpected moments. Thus, links between insight and the WCST but not D-KEFS sorting tests may suggest unawareness of illness, and treatment need does not proceed merely from difficulties finding possible categories but is more a matter of being able to shift set in the face of sudden environmental demands. As with all unanticipated results, replication in future research is needed before these findings should be afforded any weight.

There are limitations to this study. Sample size was modest in relation to the number of comparisons made. Though we made two-tailed tests despite unidirectional hypotheses, the risk of spurious findings increased. Generalization of findings also is limited by sample composition. Participants were mostly men in their 40s who were involved in treatment. It may well be that a different relationship exists between insight, symptoms, and neurocognition among women or among younger men with schizophrenia, or among those who decline treatment. Given the modest correlations found, it remains unclear as to what degree cognitive impairments affect self-awareness of what others easily perceive as illness. Future research is necessary to examine the interaction of cognitive factors with psychological and social factors, including stigma and self-esteem, that could affect self-awareness.

1. Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, et al: Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:826–836Google Scholar

2. David AS: Insight and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 156:798–805Google Scholar

3. McEvoy JP: The relationship between insight into psychosis and compliance with medication, in Insight and Psychosis, 2 nd ed. Edited by Amador X, David A. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp 311–334 Google Scholar

4. Francis JL, Penn DL: The relationship between insight and social skill in persons with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Disord 2001; 189:822–829Google Scholar

5. Lysaker PH, Bryson GJ, Bell MD: Insight and work performance in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Disord 2002; 190:142–146Google Scholar

6. Lysaker PH, Bell MD, Bryson G , et al: Psychosocial function and insight in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Disord 1998; 186:432–436Google Scholar

7. Schwartz RC: The relationship between insight, illness and treatment outcome in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q 1998; 69:1–22Google Scholar

8. Morgan KD, David AS: Neuropsychological studies of insight in patients with psychotic disorders, in Insight and Psychosis, 2 nd ed. Edited by Amador X, David A. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp 177–196 Google Scholar

9. Lysaker PH, Bryson GJ, Lancaster R, et al: Insight in schizophrenia associations with executive function and coping style. Schizophr Res 2003; 59:41–47Google Scholar

10. Smith TE, Hull JW, Israel LM, et al: Insight, symptoms and neurocognition in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:193–200Google Scholar

11. Young DA, Zakzanis KK, Bailey C: Further parameters of insight and neuropsychological deficit in schizophrenia and other chronic mental diseases. J Nerv Ment Disord 1998; 186:44–50Google Scholar

12. Mohamed S, Fleming S, Penn P, Spaulding W: Insight in schizophrenia: its relationship to measures of executive function. J Nerv Ment Disord 1999; 187:525–531Google Scholar

13. Lysaker PH, France CM, Davis LW, et al: Personal narratives of illness in schizophrenia: associations with neurocognition and symptoms. Psychiatry 2005; 68:140–151Google Scholar

14. Drake RJ, Lewis SW: Insight and neurocognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2003; 62:165–173Google Scholar

15. Lele MV, Joglekar AS: Poor insight in schizophrenia: neurocognitive basis. J Post Graduate Med 1998; 44:50–55Google Scholar

16. Wong JG: Decision-making capacity of inpatients with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. J Nerv Ment Disord 2005; 193:316–322Google Scholar

17. Kay SR, Fizszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261–276Google Scholar

18. Bell MD, Lysaker PH, Goulet JB, et al: Five component model of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1994; 52:295–303Google Scholar

19. Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH: Delis Kaplan Executive Function System: Technical Manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corporation, 2001Google Scholar

20. Spitzer R, Gibbon M, First M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. New York, Biometrics Research, 1994Google Scholar