A Review of Lewy Body Disease, an Emerging Concept of Cortical Dementia

Abstract

Dementia associated with cortical Lewy bodies on neuropathologic examination may comprise the second largest category of age-related cognitive impairment, after Alzheimer's disease. Despite its prevalence, a consensus has not yet been reached regarding the terminology, neuropathologic criteria, or clinical symptomatology of this postulated nosologic entity. Lewy body disease (LBD) is beginning to be diagnosed clinically in neuropsychiatric clinics, but universally accepted diagnostic criteria for LBD remain to be validated. In this article the authors review the literature on LBD, including both neuropathologic and clinical findings.

As many as 20% of elderly individuals may suffer from a diffuse cortical dementia that is coming to be called Lewy body disease (LBD).1 Some of the major clinical symptoms associated with this disease are cognitive impairment, parkinsonism, acute confusion, and behavioral disturbances such as delusions, hallucinations, and depression.2–4 These symptoms are common to other age-related diseases, and it has been difficult to develop universally accepted neuropathologic and clinical diagnostic criteria for LBD. Hence, LBD has often been misdiagnosed as Alzheimer's disease (AD) or vascular dementia,4–6 or it may be confused with idiopathic Parkinson's disease (PD). Misidentification of LBD patients as AD patients under the criteria developed by the U.S. National Institute for Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) has been reported as a common error in therapeutic trials for AD.7 In fact, it has been suggested that up to 36% of patients meeting NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for AD exhibit Lewy body (LB) pathology at autopsy.8 Major objectives of this article are to review the literature addressing the neuropathologic and clinical correlates of LBD and to discuss potentially useful diagnostic criteria for this disease entity.

Numerous terms have been used to categorize dementia associated with LBs,9 including the LB variant of AD,2senile dementia of the LB type,4diffuse LB disease,10,11 and PD in AD.12 In the present article, we use the term LBD (Lewy body disease) to refer to the spectrum of syndromes resulting from the presence of LBs in the brainstem and cortex. (Readers should note that the term LBD was not necessarily used by the authors cited.)

NEUROPATHOLOGY OF LEWY BODY DEMENTIA

Lewy bodies (LBs) have been the pathologic hallmark of PD since 1919, when Tretiakoff13 linked the clinical signs and symptoms of parkinsonism with degeneration of the substantia nigra. He identified the intracellular inclusions described 7 years earlier by Frederich Lewy14 in patients suffering from PD. The first cases of LBD were documented in 1961 by Okazaki et al.,15 who observed the presence of widespread LBs in the cerebral cortex in 2 demented elderly individuals. Although neither patient presented with PD, and gross examination of the substantia nigra at autopsy failed to reveal any pallor, LBs were abundant in the substantia nigra, in the locus ceruleus, and throughout the cerebral cortex.

In following years, several case reports of demented patients with the pathologic substrate of widespread LBs were published, predominantly by Japanese investigators.11,16,17 Based on neuropathologic findings, different subtypes of LBD have been defined. Kosaka et al.17 divided the diseases with Lewy bodies into three categories: “brainstem” type (LB identified only in diencephalon and brainstem), “transitional” (numerous LB in diencephalon and brainstem and few in the cerebral cortex and basal ganglia), and “diffuse” (LB widely distributed in cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, diencephalon, and brainstem).

Intraneuronal Inclusions in LBD

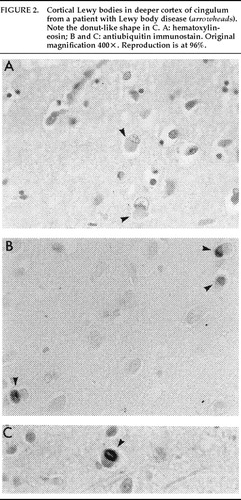

LBs (Figures 1 and 2) and pale bodies (Figure 1B) are the characteristic intraneuronal inclusions observed in LBD.18 Two morphologic types of LB exist: classic and cortical. Both are round, intraneuronal eosinophilic structures. However, the classic LB is more easily identified because of its denser staining characteristic (Figures 1B and 1C) and the presence of a surrounding halo (Figure 1A). These two types of LBs may also be differentiated by their respective locations: classic LBs are located predominantly subcortically, whereas cortical LBs are found in neocortical neurons of deep cortical layers (Figure 2A). Pale bodies have a granular structure and lack the distinctive two parts of classical LBs; they are easily noticed because they displace neuromelanin and lipofuscin to the periphery. Pale bodies may be found in neurons also containing classical LBs. Although some people suggest that pale bodies are the precursors of LB, this has not been demonstrated.

Complicating the diagnosis of LBD is the nonspecificity of LBs for LBD. LBs are found in the neuromelanin-containing neurons of about 5% of elderly, nonparkinsonian individuals. They are also evident in as many as 25%12 to 67%19 of patients with otherwise typical AD who may also have LB pathology. This range of LB incidence in AD may be conceptual (that is, some people may consider AD with LB what others would call LBD) or may be due to the inclusion of globose tangles (which may be ubiquitin positive) in the LB counts.

Differentiating Neuropathologic Features of LBD

With the exception of pallor of the substantia nigra, which is a common macroscopic finding in the LBD, the gross characteristics of this disease are nonspecific. One neuropathologic characteristic that may help distinguish between LBD and AD is the presence of ubiquitin-positive neurites in CA2/3 of hippocampus (Figure 3).20 Although such pathology has been observed in PD and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), it has not been observed in pure AD or other corticodegenerative diseases.21

Microscopically, the majority of brains examined at autopsy displaying significant numbers of cortical LBs also have subcortical LBs and senile plaques, as well as some dystrophic neurites and neurofibrillary tangles. Thus, the neuropathologic distinction between LBD and PD and between LBD and AD is difficult. For example, in one study,22 histopathologic review of 100 clinically diagnosed PD patients revealed cortical LBs in all cases.

The neuropathologic overlap between LBD and AD is perhaps even more profound. For example, one group of researchers reviewed the microscopic characteristics of 147 demented patients23 who met National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD) criteria for the diagnosis of AD, and found that 19% had plaques and LBs and 10% evidenced plaques, tangles, and LBs (65% had plaques and tangles only, and 6% had plaques only). Hence, these researchers determined that two-thirds of the LB-containing brains had plaque-only AD and the other third had plaques-and-tangles AD. This finding also suggested that two-thirds of the plaque-only AD cases had LBs. Because all of the patients studied had the diagnosis of AD, this study does not provide any information about the proportion of cases with DLB and no AD pathology. In a different study, Forstl et al. observed LBs in 12% of autopsy cases carrying the clinical diagnosis of AD.24 All cases had concomitant AD pathology, which was more mild than that observed in a similar group of age-matched AD control subjects. A small study comparing pure LBD, LBD with AD changes, AD only, and nonpathologic control subjects25 found significantly higher neuronal counts in LBD-only brains compared with those with concomitant AD pathology.

Neuropathologic Diagnosis of LBD

Since the discovery of LBD, different investigators have used different neuropathologic criteria for its diagnosis, limiting the possibilities of cross-study comparisons and a unified conceptualization of this disease. Standard diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of LBD have been proposed recently as a result of the First International Workshop of the Dementia With Lewy Bodies Consortium.26 In using these criteria, the only histopathologic feature essential for the diagnosis is the presence of LBs. Associated, but not necessary, features are Lewy-related neurites (better seen with ubiquitin immunostain in CA2/3 of hippocampus, amygdala, nucleus basalis, and brainstem nuclei); plaques of all morphologic types; neurofibrillary tangles; neuronal loss in substantia nigra, locus ceruleus, and nucleus basalis of Meynert; microvacuolation and synapse loss; and neurochemical abnormalities and neurotransmitter deficits.

The newly proposed criteria specify concrete and practical guidelines for the diagnosis and include five anatomic locations to be examined in addition to the substantia nigra. These regions are transentorrhinal cortex, cingulate gyrus, and temporal, frontal, and parietal cortices. Each area is scored semiquantitatively, ranging from 0, where no LBs are identified, to 2, where more than 5 LBs are present. Individual scores from the different anatomic regions are then summated, and the total score serves as an index of the histopathologic grade of LBD: when the total score is 0 to 2, the disease is characterized as “brainstem predominant”; a score of 3 to 10 corresponds with “limbic” or “transitional” LBD; the most severe form of the disease, indicated by scores between 11 and 15, is called “neocortical” LBD.

Although these criteria appear to provide useful guidelines by consensus of experts in the field, they still must be tested empirically. Because much of what is known about LBD is based on retrospective study of patients with an autopsy-confirmed diagnosis of LBD, variations in neuropathologic diagnosis seriously complicate and limit attempts to uniformly characterize this disease. The development of these consensus criteria represents a significant step toward clarifying the diagnosis of LBD; however, specific criteria likely will require modification before they can be used as a diagnostic tool.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

One might expect that LBD patients would present with a combination of parkinsonian and Alzheimer-like features, and this seems to be the case.2 The clinical profile emerging from independent, retrospective studies based on autopsy diagnosis includes 1) a cortical Alzheimer-like dementia characterized by loss of memory, orientation, and visuospatial skills; 2) extrapyramidal signs of a more mild nature than seen in classic PD; and 3) psychiatric symptoms including hallucinations, delusions, and/or depression. Fluctuations in cognitive state and disturbances in consciousness have also been reported,3,4 as have adverse reactions to antipsychotic agents.3,27–30 Each of these categories of behavioral symptomatology is discussed in more detail in the following sections. Other, less commonly reported symptoms are severe weight loss31,32 and orthostatic hypotension.33

Demographics

The prevalence of this disease appears to be higher in males than in females,3,6,24,27,33–37 in a ratio of about 2:131,37 or higher.27,33,35 The age at onset ranges between 50 and 83 years,31,33,38 and the reported mean age at death varies from 68.4 years to 92 years.33 The reported duration of the illness is equally variable, ranging from less than 1 year to 20 years,31,38 with a mean of 3.34 to 6 years.34,38,39 The crude prevalence and incidence are not yet known.

A positive family history for AD in at least one first-degree relative of patients affected with LBD has also been reported.2,34 Recent evidence suggests that the apolipoprotein E4 (APOE E4) allele, in particular, is a major risk factor for developing LB pathology.40,41 However, in one study of 122 autopsied patients, 39.2% of AD cases had the APOE E4 allele, compared with only 6.25% to 29% of LBD cases.42 Hence, further investigation of a genetic predisposition for developing LBD is warranted.

Neuropsychological Features

The distinguishing characteristics of dementia associated with LBD have not been well studied or described, although impairments of memory,27,33,38 language, and visuospatial skills27,38 have been noted. Since this pattern of cognitive deficits is similar to that observed in AD,43 clinicians face the difficult issue of differentiating these two dementing illnesses. Because extrapyramidal features are also common in LBD, the differential diagnosis is further complicated by dementia associated with PD, which typically is characterized by impairments in short-term memory, concept formation, and mental flexibility.44 Despite the reportedly high prevalence of dementia in PD,45 systematic comparisons of LBD and demented PD patients are lacking in the literature.

Across studies assessing differences between LBD and AD dementia, results have been mixed and seem to vary with differing methodologies. Some evidence from retrospective studies suggests that the dementia of LBD is less severe than that of AD when patients are matched on the basis of age. For example, on gross screening measures such as the Blessed Information-Memory-Concentration test (IMC),46 LBD patients have evidenced less severe impairments than AD patients,3,4 particularly on questions involving short-term memory.3 In addition, AD patients showed more severe deterioration than LBD patients.4 However, when matched on the basis of disease duration,47 LBD and AD patients performed comparably on gross cognitive screening measures, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),48 the IMC, and the Dementia Rating Scale.49

Few studies are available in which performance on comprehensive neuropsychological test batteries was used to make comparisons between these populations. In one such study, where patient groups were first matched on the basis of IMC scores, LBD patients evidenced greater impairments than AD patients on standardized measures of attention, verbal fluency, and visuospatial/constructional skills.2 Unfortunately, the matching procedure used in this study may have conferred a bias against the AD patients, who typically perform more poorly on the IMC.3,4 In another study using a standardized neuropsychological test battery, significant performance differences between AD and LBD patients were not found.47

Our impression from these studies is that methodological differences, including differing definitions of the disease (e.g., differing neuropathologic criteria), limit between-study comparisons, and consequently no clear neuropsychological profile of LBD has emerged. Procedurally, the basis on which subjects are matched—age or disease duration—is one variable that critically affects the obtained results. Furthermore, it appears that gross and standardized psychometric tests may not be sensitive to the morphologic differences between LBD and AD dementia.

Prospective studies using more refined tests have revealed greater impairments in LBD than AD patients on some cognitive tasks.50,51 LBD patients (diagnosed with criteria of McKeith et al.3) performed more poorly than AD patients on delayed-matched-to-sample,51 a task requiring subjects to remember a presented stimulus over a designated delay and then to select that stimulus among a choice of distractors. The poorer performance of LBD patients may suggest the early involvement of temporal lobe structures, which are critical substrates to the successful completion of this task.52 LBD patients also have shown greater impairments than AD patients on a conditional learning paired associate task.50

Certainly, further exploration is needed of the characteristic differences between AD dementia and LBD dementia. Such studies should also include PD patients with dementia, since comparisons with this group are currently lacking and are needed to facilitate accurate differential diagnosis of LBD. A prerequisite for the success of this proposed research will be more precise neuropathologic criteria for LBD. Future investigations should include quantitative and qualitative assessments of AD, PD, and LBD patients across multiple cognitive domains. In addition, it seems likely that standardized psychometric tests may be insufficient for detecting differences between these patient populations and that more sensitive measures will have to be developed and used.

The underlying neuropathological mechanisms of the dementia associated with LBD also need to be elucidated. Whether the observed dementia is due to cortical LBs, brainstem LBs, neuronal loss, and/or AD-like neuropathology is not known. A few studies have revealed a relationship between cortical LB density and severity of dementia,47,53 but the predictive relationship between these variables has not always been observed.43 There is still no consensus on the relative contribution of AD-like plaques and tangles, also common in LBD,2,4,33–35 to LBD dementia.47,54–55 Although counts of neurofibrillary tangles in neocortex have been shown to be significantly correlated with dementia in AD patients, Samuel et al.47 reported that this relationship was comparatively weak in LBD patients. Subcortical pathology, such as neuronal loss in the nucleus basalis of Meynert, has been associated with other dementing syndromes,35,56 although researchers have thus far failed to support the relationship between brainstem LBs and degree of dementia.4

Cognitive Fluctuations and Disturbances of Consciousness

In findings related to dementia, some investigators consistently have noted characteristic fluctuations in cognitive ability in patients with LBD,3,16,38 leading some to suggest that this feature may be a distinguishing clinical feature of this illness.4 These fluctuations are reported to occur in the presence of periods of relative lucidity and intact memory function and may be followed by an acute or subacute confusional state. During these episodes, patients have been described as “glazed looking” and showing “generalized twitching,”3 “muddled” one day and “alert” the next.38 Furthermore, it has been suggested that this type of fluctuation is not restricted to cognitive functioning, but may generalize to other mental, physical and behavioral capacities, causing extreme reductions in consciousness and arousability.3 Some researchers suggest that this type of “switching off” does not occur until later stages of the disease,3 whereas others report a 67% incidence of fluctuations early in the progression of LBD, compared with an incidence of 13% during later stages.57

There is not yet a consensus on the significance of this feature, nor on any standardized measure for its occurrence. Certainly, not all researchers have observed fluctuations in cognitive state in affected patients, and we conclude that the incidence of cognitive fluctuation in LBD is unknown. Most clinicians are not likely to observe these fluctuations firsthand in the context and time limitations of an office visit, or possibly not even during a short-term hospital stay. Relying on the accounts of caregivers may also be troublesome, particularly if informants do not offer the verbatim description “fluctuations in consciousness,” which few are likely to do. Directly asking caregivers about the presence of this feature may be leading, as all patients are bound to experience higher and lower points throughout a given period of time. Studies aimed at establishing objective means of assessing cognitive fluctuations in relevant patient populations are needed.

Neurological Findings

Extrapyramidal signs commonly appear during the LBD disease course, affecting at least 80% of this population.4 These neurological findings are not surprising given the common neuropathologic finding of LBs in the substantia nigra of affected individuals.38 It is generally agreed, however, that the parkinsonism observed in LBD is more mild than that observed in PD patients2,3,31,32 and that the classical PD triad of tremor, akinesia, and rigidity is not likely to appear.4 Some researchers suggest that parkinsonism may be more likely to occur at later stages of the disease, a suggestion that seems supported by the finding that patients who do not show extrapyramidal signs have shorter survival durations.27,58 We do not yet know with any reliability the course of extrapyramidal findings in LBD or their diagnostic and prognostic significance.

The extrapyramidal signs observed in LBD may be qualitatively different from those exhibited in PD, although consensus is lacking as to the characteristics of these differences. Determination of the most prominent extrapyramidal feature of LBD has varied across investigators, from rigidity24,31 to gait impairment32 to falling.3 In one recent study,59 the presence of myoclonus, absence of rest tremor, or no trial or response to levodopa was 10 times more likely to occur in LBD than in PD. However, another study by some of the same researchers revealed a higher frequency of bradykinesia in LBD patients compared with PD patients, a nonsignificant trend toward less resting tremor in LBD patients, and a similarly high response to levodopa in both populations; taken together, these characteristics could not reliably distinguish LBD from PD patients.60 Contrary to the latter findings regarding resting tremor, the absence of resting tremor in LBD was not supported by a separate study in which the majority of 70 autopsied LBD patients had presented with tremor onset.61

Hence, reliable qualitative characteristics of the extrapyramidal features observed in LBD cannot be determined. Some researchers even contend that at least 30%31 to 40%38 of LBD patients show extrapyramidal symptoms that are indistinguishable from PD. Further research investigating qualitative differences in extrapyramidal signs between PD and LBD patients is still needed.

Falls

In relation to observed parkinsonism, some researchers propose that repeated, unexplained falls are a prominent feature of LBD.3,36 In one retrospective study of 21 LBD cases, repeated falling was reported by 38% of patients during the initial clinical visit. For 3 of these patients, episodes of falling were frequent, occurring approximately 20 times per week during the time period immediately preceding the clinical consultation. The progression of clinical symptoms was not different for LBD patients who experienced falling compared with those who did not.3

Although impaired cognition, rather than age, has been shown to be related to the incidence of falls in the elderly,62,63 falling may be significantly more prevalent in LBD than in other age-related dementias, such as AD3,36 and multi-infarct dementia (MID).36 In one retrospective study comparing the clinical histories of patients affected by different age-related dementing illnesses, 50% of LBD patients, compared with 23.8% of AD and 33.3% of MID patients, had recorded histories of repeated, unexplained falls.36 Research comparing the extrapyramidal symptoms of LBD and PD59,60,64 has not specifically included repeated falling as a measure.

Although some researchers have described these repeated falls as “unexplainable,”3,36 the documented extrapyramidal features of LBD, including rigidity,31 postural instability,2 and orthostatic hypotension,33,65 may account at least in part for episodes of falling. Nonetheless, rigidity66 and postural instability,2 as well as dementia, have been observed as frequently in AD patients, in whom falling is not as prevalent.3,36 These findings suggest that neither dementia nor these extrapyramidal signs alone can account for the frequency of reported falls in LBD patients. Significant neuronal loss in the substantia nigra of LBD cases24 may account for at least some of the observed falling in these patients. Comparisons of falling rates between PD and LBD patients are still needed and would be useful in determining the relationship between substantia nigra neuronal loss, corresponding extrapyramidal features, and falling.

Psychiatric Correlates

Psychiatric symptoms of depression, hallucinations, and delusions have almost always been reported as a feature of LBD.3,32,33,37,38 However, the reported rate, severity, and profile of psychiatric symptoms exhibited by LBD patients have been inconsistent. In one study, more than 83% of LBD patients presented with prominent psychiatric symptoms, even in the context of mild to moderate dementia.32 Others have reported a lower rate of psychiatric symptoms in LBD, ranging from 17.9% to 22.2%34 to 53%.38 These differences in observed prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in LBD may reflect differences in methodology, including thoroughness of examination and clinical notes, size of the sample, and neuropathologic criteria for diagnosing LBD.

The specific profile of psychiatric symptoms exhibited by LBD patients varies across studies and individuals. Several researchers have reported hallucinations and delusions in up to 80% of LBD patients,3,33 but others report a lower incidence of these two symptoms.24,31,34 In one group of LBD patients, neither hallucinations nor delusions were experienced by any patient, and only a minority were depressed.2 A similarly low frequency of depression was reported in another sample;31 however, hallucinations were observed in 15% and paranoia in 12% of cases. Again, there does not seem to be a consensus yet concerning features and frequency of psychiatric symptomatology.

The psychiatric dimension of LBD is important for diagnosis because hallucinations, delusions, and depression are reported also in AD and in PD. In one study comparing the rates of different psychiatric symptoms across AD, PD, and LBD populations, investigators found that LBD patients had rates of depression and hallucinations similar to those of PD patients (50%–60%), but rates of delusions comparable to those observed in AD (approximately 50%).37 The LBD patients described in that study also tended to experience visual hallucinations, paranoid delusions, and depression refractory to treatment. The quality (auditory versus visual) of hallucinations and delusions did not differ across groups. In that particular patient cohort, the absence of psychiatric symptoms in LBD was rare, suggesting that psychiatric features (hallucinations, delusions, depression) may be especially useful in making the diagnosis of LBD. Additional research comparing psychiatric symptomatology in LBD, PD, and AD populations is necessary to facilitate accurate clinical and differential diagnosis of LBD.

Adverse Reactions to Antipsychotic Agents

Adverse reactions to antipsychotic and tricyclic antidepressant agents by LBD patients have also been frequently reported, so much so as to be recommended by some investigators as a clinical clue to the diagnosis of LBD.3,28 These reactions have included confusion,27 mental impairment, and hallucinations29,30 and have even been fatal.28 In one retrospective study,28 81% of 16 LBD patients given antipsychotic agents such as haloperidol, thioridazine, trifluoperazine, flupenthixol, and sulpiride had adverse reactions, compared with only 7% of AD patients. Fifty-four percent of the affected LBD patients had reactions that were considered severe. Patients receiving antipsychotic agents showed a higher mortality rate than those who did not receive antipsychotic agents or those who had mild reactions to these drugs.

The utility of known adverse reactions to antipsychotic agents in the clinical diagnosis of LBD requires further validation. Because patients other than those with LBD also may experience adverse reactions to antipsychotic drugs, comparisons of incidences of adverse reactions across different patient populations are needed.

Progression of Clinical Symptoms

The clinical progression of LBD is not clear and may vary across individuals. In general, LBD patients initially present with a dementing syndrome and possibly some neuropsychiatric disturbance27,31,33,35,58 and/or mild parkinsonism. A smaller percentage of patients initially present with parkinsonism, which is followed by dementia.24,35,38 The general rate of progression has not been well documented.

It is likely that what is now collectively categorized as LBD will require further refining as more is learned about both the clinical and the neuropathologic correlates of the disease. Filley,65 for example, has proposed an association between density and location of LBs and specific syndromes, ranging from incidental LBs (which are asymptomatic) to PD to diffuse LBD. He associates brainstem LBs with movement disorders, cortical LBs with dementia, and the involvement of limbic areas with psychosis and depression.

Kosaka34 suggests instead that differences in the clinical manifestation of LBD reflect differences between proposed “common” and “pure” forms of this disease, in which “common” cases are characterized by the coexistence of cortical LBs, plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles, and “pure” cases consist of cortical LBs only. According to Kosaka, “common” cases, comprising 75% of LBD patients, initially present with memory disturbance or a psychotic state followed by dementia. “Pure” LBD patients, in contrast, present with parkinsonism as an initial symptom and are usually young adults.

Additional classification indices have been proposed by Perry et al.,4 who distinguish “senile dementia of the LB type” from “LBD” on the basis of extent and loci of neuropathologic lesions. The phenotypic variability of this disease is also being explored.67 The description and diagnosis of subcategories or separate nosologic entities of LBD have yet to be established; these will likely be refined with continued research and understanding of the disease process.

PROPOSED CLINICAL CRITERIA

As we enter the era of experimental therapeutics in dementia, we need to develop sensitive and accurate diagnostic criteria for identifying LBD in life. In current diagnosis, LBD is often confused with AD, MID, and possibly also PD with dementia. In one retrospective study using neuropathologic diagnosis, 15% of LBD patients met NINCDS clinical criteria for probable AD, 35% met DSM-III-R criteria for DAT (which were the most current DSM criteria at the time the patients were evaluated), and 50% met NINCDS criteria for possible AD.6 In another study, 36% of patients meeting NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for AD exhibited LB pathology at autopsy.8 Hence, accurate differential diagnosis of LBD from other age-related dementias remains a challenge to clinicians.

Some researchers recommend a diagnosis of LBD when attentional, verbal, and visuospatial deficits present concurrently with mild extrapyramidal features.2 Others suggest that a progressive dementing syndrome with gait disorder, psychiatric symptoms, and burst patterns on EEG warrants LBD classification.32 It has also been suggested that mild neuropsychiatric symptoms, mild cognitive impairment, and minor extrapyramidal signs may be indicative of an early or mild form of the disease.9

There is some evidence suggesting that neuroimaging may be useful for making a clinical diagnosis of LBD.24 Retrospective analysis of CT scans of 5 AD and 5 LBD patients, studied longitudinally and matched for age and gender, revealed significantly larger frontal subdural spaces for LBD patients compared with AD patients (i.e., frontal atrophy). This severe frontal atrophy may reflect the degeneration of mesocortical dopaminergic neurons to the frontal lobes.68 All patients showed severe cortical atrophy and ventricular enlargement, and the groups could not be distinguished on this basis. The researchers involved in this study recommend that a diagnosis of LBD be made when 1) NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for AD are met and 2) patients additionally present with severe rigidity and frontal atrophy. However, another study comparing MRI data of LBD and AD patients failed to reveal significant differences.69 Further validation of the diagnostic utility of frontal lobe atrophy on CT and MRI is needed.

Nottingham Group Criteria

One of the first sets of structured criteria for the clinical diagnosis of LBD was proposed by the Nottingham Group for the Study of Neurodegenerative Diseases in 1991; these criteria are listed in Table 1.70 These criteria do not appear to have been in use since the development of more recent criteria. The top part of Table 1 specifies the criteria for a diagnosis of probable dementia associated with cortical LBs, and the bottom part lists the criteria for possible dementia. For both sets, all criteria (A, B, C, and D) must be met to make a diagnosis of LBD.

Despite a high specificity, these criteria were not sensitive to LBD in a different population,6 especially when parkinsonism due to antipsychotic agents was not considered adequate for meeting the parkinsonism criterion. Hence, McKeith et al.6 have suggested that the Nottingham criteria may be most sensitive to those patients diagnosed with PD who later develop neuropsychiatric symptoms consistent with LBD. However, these criteria are less sensitive to LBD patients who do not present with parkinsonism. Certainly, for retrospective study, the accuracy and thoroughness of medical documentation greatly influence outcome sensitivity measures; if medical care providers did not look for, or note, parkinsonism (or any other symptom) as an important clinical feature in individual patient records, this feature would not be deemed essential for a diagnosis of LBD, increasing the rate of misdiagnosis.

McKeith Group Criteria

In 1992, McKeith et al.3 proposed another set of criteria for clinically diagnosing LBD. These criteria, shown in Table 2, are based on retrospective study of 21 autopsy-determined LBD cases.

Applied retrospectively to one sample of LBD and AD patients,3 these criteria identified 71% of LBD cases on initial presentation, and 86% between presentation and death. Although some of the LBD cases also met the clinical criteria for AD, no cases of AD met these proposed criteria for LBD. Applied to another sample of LBD, AD, and MID patients, these criteria yielded a 74% sensitivity rate, averaged across four raters, and a specificity of 95%.36 The interrater reliability was generally quite high and was comparable to that of commonly used clinical criteria for AD. However, agreement was highest and diagnosis most accurate (90% versus 55% sensitivity) among more experienced clinicians compared with less experienced clinicians. (This comparison of accuracy between more and less experienced clinicians was not decided a priori.) The most common error among the less experienced clinicians was the failure to recognize cognitive fluctuations unique to LB dementia. As discussed previously, clarification and objective standards for identifying this fluctuation are needed and may improve the diagnostic utility of the McKeith et al.3 criteria.

Consensus Criteria

The most recent set of operational criteria for LBD, largely based on the criteria of McKeith et al., was developed during the 1996 Proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Consortium on Dementia with LBs.26 The report from this consortium appears to acknowledge the difficulty of assessing fluctuating cognition; the consensus criteria for the clinical diagnosis for LBD (termed dementia with LBs) include this as a core, but not essential, feature of the disease. As outlined in Table 3, the only essential criterion is a loosely defined dementia. Using these criteria, 2 of 3 additional symptoms are necessary for a diagnosis of probable LBD, and only 1 for a diagnosis of possible LBD (see item B, Table 3). Other features, such as repeated falls, delusions, and neuroleptic sensitivity, are considered only “supportive” of the diagnosis, but not fundamental (see item C, Table 3). These criteria have not yet been tested in autopsy-based or prospective studies.

Most of what is known about the clinical features of LBD, and used to develop operational criteria for its clinical diagnosis, is based on retrospective study and analysis. Such procedures have clear limitations that preclude the possibility of strongly supporting any single characteristic or set of criteria as predictive of LBD. Hence, the current direction for clinical research on LBD and the validation of diagnostic criteria should be comprehensive prospective studies, through to autopsy, of patients presumed to have LBD. Once initial, prospective clinicopathologic correlations have been determined, it will be necessary to cross-validate these relationships in another sample. Such research will be complex and likely will take many years; however, it may be the only alternative for determining if LBD is a distinct nosologic entity that can be diagnosed clinically with an acceptable degree of accuracy.

THERAPEUTICS

There are no known therapeutic trials or treatments for LBD. Once accurate clinical diagnoses of LBD can be made, medications deemed useful for AD and PD may also be found beneficial for the LBD population. Cholinergic and dopaminergic systems appear to be critically involved in LBD, although other neurotransmitter systems are likely affected as well.

Several lines of evidence suggest that patients with LBD may benefit from cholinergic replacement therapy. Compared with AD patients, LBD patients show markedly reduced cortical choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) activity,2,10,29,30,32 particularly in the temporal29,30 and parietal30 neocortices. Reduced parietal ChAT activity has been correlated with lower mental status scores46 in some LBD patients,4 but this finding has not been replicated.35

Cholinergic agonists have been tried as a treatment for AD, and it has been suggested that they may be more effective in LBD because remaining cortical neuronal systems are not grossly affected by neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.28 At least in one study, however, necropsy-confirmed AD and LBD cases responded similarly to tacrine, a cholinergic agonist.71 LBD patients with a tendency toward hallucinations show relatively greater reduction in ChAT activity compared with other LBD patients,29,30 and therefore it has been suggested that these LBD patients, in particular, may be better responders to cholinergic drugs. The question may be raised still as to whether “responders” to cholinergic drugs in previous clinical AD trials actually carry a diagnosis of LBD.72

The dopaminergic system also appears to be involved in LBD, although the effects of dopaminergic therapy have been mixed. Positive responses to levodopa in the treatment of presenting parkinsonian motor symptoms have been noted,27,38 but this finding has not been consistent;27,29,30,32 in some patients, levodopa treatment has actually elicited adverse side effects such as confusion,27 mental impairment, and hallucinations.29,30 One case study reports the benefit of clozapine in treating the psychotic symptoms of a patient with LBD.73

CONCLUSIONS

Dementia associated with LB formation in the brainstem and cerebral cortex has recently been recognized as an important cause of dementia in older adults. In this article we have reviewed various aspects of LBD, including operational criteria for clinical and neuropathologic diagnosis. As yet, no set of clinical or neuropathologic criteria has received ample empirical validation, although various sets of criteria have been proposed over the past decade. The current challenge for investigators of this disease is the establishment of detailed, prospective clinical studies of patients presumed to have LBD, performed in conjunction with neuropathological studies. Only with such rigor will we be able to determine whether LBD does, in fact, constitute a nosologically distinct entity that can be diagnosed in life and for which specific therapeutic intervention may be tried.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to Dr. James Powers for his thorough and thoughtful review of this manuscript. This project was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging Alzheimer's Disease Center (AG08665) and a Neurobiology of Aging Training Grant (AG00107).

FIGURE 1. Classic Lewy bodies in the substantia nigra of a patient with Parkinson's disease (A and C, arrowheads; B, triangles). Note the surrounding halo in A and the laminar concentrical structure in C; multiple Lewy bodies in a single neuron as well as a pale body in (arrow); and perivascular melanophages in A (arrows). Hematoxylin-eosin; original magnification 200× (A and C) and 400× (B). Reproduction is at 75% of original.

FIGURE 2. Cortical Lewy bodies in deeper cortex of cingulum from a patient with Lewy body disease (arrowheads). Note the donut-like shape in C. A: hematoxylin-eosin; B and C: antiubiquitin immunostain; all panels, original magnification 400×.

FIGURE 3. Ubiquitin-positive neurites in CA2/3 layer of hippocampus from a patient with Lewy body disease. Anti-ubiquitin immunostain; original magnification 400×. Reproduction is at 75% of original.

|

|

|

1. Perry R, Irving D, Blessed G, et al: Clinically and pathologically distinct form of dementia in the elderly. Lancet 1989; 1:166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hansen L, Salmon D, Galasko D, et al: The Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease: a clinical and pathological entity. Neurology 1990; 40:1–8Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. McKeith I, Perry R, Fairbairn A, et al: Operational criteria for senile dementia of Lewy body type (SDLT). Psychol Med 1992; 22:911–922Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Perry R, Irving D, Blessed G, et al: Senile dementia of Lewy body type: a clinical and neuropathologically distinct form of Lewy body dementia in the elderly. J Neurol Sci 1990; 95:119–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kondo N: [A study on the difference between clinical and neuropathologic diagnoses of age-related dementing illnesses: correlations with Hachinski's ischemic score (Japanese).] Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 1995; 97:825–846Medline, Google Scholar

6. McKeith I, Fairbairn A, Perry R, et al: The clinical diagnosis and misdiagnosis of senile dementia of Lewy body type (SDLT). Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:324–332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Derouesne C: [Dementia: diagnostic problems (French).] Therapie 1993; 48:189–193Medline, Google Scholar

8. Dickson D, Ruan D, Crystal H, et al: Hippocampal degeneration differentiates diffuse Lewy body disease (DLBD) from Alzheimer's disease: light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry of CA2-3 neurites specific to DLBD. Neurology 1991; 41:1402–1409Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hansen L, Galasko D: Lewy body disease. Curr Opin Neurol 1992; 5:889–894Google Scholar

10. Dickson D, Davies P, Mayeux R, et al: Diffuse Lewy body disease: neuropathologic and biochemical studies of six patients. Acta Neuropathol 1987; 75:8–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Yoshimura M: Cortical changes in the parkinsonian brain: a contribution to the delineation of “diffuse Lewy body disease.” J Neurol 1983; 229:17–32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Ditter S, Mirra S: Neuropathologic and clinical features of Parkinson's disease in Alzheimer's disease patients. Neurology 1987; 37:754–760Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Tretiakoff C: Contribution a létude de l'anatomie pathologique du locus niger de Soemmering avec quelques deductions relatives à la pathogenie des troubles du tonus musculaires et de la maladie de Parkinson [Contributions to the study of the substantia nigra of S;auommering with relation to the pathogenesis of the muscular tone problems in Parkinson's disease]. Thesis, University of Paris, 1919Google Scholar

14. Lewy FH: Paralysis agitans, I: pathologische anatomie, in Handbuch der Neurologie, edited by Lewandowsky M. Berlin, Springer, 1912, pp 920–933Google Scholar

15. Okazaki H, Lipkin LE, Aronson SM: Diffuse intracytoplasmic ganglionic inclusions (Lewy type) associated with progressive dementia and quadriparesis in flexion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1961; 20:237–244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Woodard JS: Concentric hyalin inclusion body formation in mental disease: analysis of 27 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1962; 21:442–449Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kosaka K, Matsushita M, Oyanagi S, et al: A clinicopathological study of the “Lewy body disease.” Psychiatria et Neurologia Japonica 1980; 82:292–311Medline, Google Scholar

18. Forno LS: Neuropathology of Parkinson's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1996; 55:259–272Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Jellinger K: Morphology of Alzheimer's disease and related disorders, in Alzheimer's disease: epidemiology, neuropathology, neurochemistry and clinics, edited by Maurer K, Riederer P, Beckman H. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1990, pp 61–70Google Scholar

20. Dickson DW, Schmidt ML, Lee VMY, et al: Immunoreactivity profile of hippocampal Ca2/3 neurites in diffuse Lewy body disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1994; 87:269–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Kim H, Gearing M, Mirra SS: Ubiquitin positive Ca2/3 neurites in hippocampus coexist with cortical Lewy bodies. Neurology 1995; 45:1768–1770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, et al: Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992; 55:181–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Hansen LA, Masliah E, Galasko D, et al: Plaque-only Alzheimer disease is usually the Lewy body variant, and vice versa. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1993; 52:648–654Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Forstl H, Burns A, Luthert P, et al: The Lewy body variant of Alzheimer`s disease: clinical and pathological findings. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:385–392Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Lippa CF, Smith TW, Swearer JM: Alzheimer's disease and Lewy body disease: a comparative clinicopathological study. Ann Neurol 1994; 35:81–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al: Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB). Neurology 1996; 47:1113–1124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Gibb W, Luthert P, Janota I, et al: Cortical Lewy body dementia: clinical features and classification. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1989; 52:185–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. McKeith I, Fairbairn A, Perry R, et al: Neuroleptic sensitivity in patients with senile dementia of Lewy body type. BMJ 1992; 305:673–678Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Perry E, Kerwin J, Perry R, et al: Cerebral cholinergic activity is related to the incidence of visual hallucinations in senile dementia of Lewy body type. Dementia 1990; 1:2–4Google Scholar

30. Perry E, Marshall E, Kerwin J, et al: Evidence of a monoaminergic-cholinergic imbalance related to visual hallucinations in Lewy body dementia. J Neurochem 1990; 55:1454–1456Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Burkhardt C, Filley C, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B, et al: Diffuse Lewy body disease and progressive dementia. Neurology 1988; 38:1520–1528Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Crystal HA, Dickson DW, Lizardi JE, et al: Antemortem diagnosis of diffuse Lewy body disease. Neurology 1990; 40:1523–1528Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Kuzuhara S, Yoshimura M: Clinical and neuropathologic aspects of diffuse Lewy body disease in the elderly. Adv Neurol 1993; 60:464–469Medline, Google Scholar

34. Kosaka K: Diffuse Lewy body disease in Japan. J Neurol 1990; 237:197–204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Kosaka K: Dementia and neuropathology in Lewy body disease. Adv Neurol 1993; 60:456–463Medline, Google Scholar

36. McKeith I, Fairbairn A, Bothwell R, et al: An evaluation of the predictive validity and inter-rater reliability of clinical diagnostic criteria for senile dementia of Lewy body type. Neurology 1994; 44:872–877Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Klatka L, Louis E, Schiffer RB: Psychiatric features in diffuse Lewy body disease: a clinicopathologic study using Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease comparison groups. Neurology 1996; 47:1148–1152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Byrne E, Lennox G, Lowe J, et al: Diffuse Lewy body disease: clinical features in 15 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1989; 52:709–717Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Dalla Barba G, Boller F: Non-Alzheimer degenerative dementias. Curr Opin Neurol 1994; 7:305–309Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Katzman R, Galasko D, Saitoh T, et al: Genetic evidence that the Lewy body variant is indeed a phenotypic variant of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Cogn 1995; 28:259–265Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Lippa C, Smith T, Saunders A, et al: Apolipoprotein E genotype and Lewy body disease. Neurology 1995; 45:97–103Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Galasko D, Saitoh T, Xia Y, et al: The apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 is overrepresented in patients with the Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1994; 44:1950–1951Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. DeVos R, Jansen E, Stam F, et al: Lewy body disease clinico-pathological correlations in 18 consecutive cases of Parkinson's disease with and without dementia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1995; 97:13–22Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Huber S, Cummings J (eds): Parkinson's Disease: Neurobehavioral Aspects. New York, Oxford University Press, 1992Google Scholar

45. Brown R, Marsden C: How common is dementia in Parkinson's disease? Lancet 1984; 1:1262–1265Google Scholar

46. Blessed G, Roth M, Tomlinson B: The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry 1968; 114:797–811Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Samuel W, Galasko D, Masliah E, et al: Neocortical Lewy body counts correlate with dementia in the Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1996; 55:44–52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Mattis S: Mental status examination for organic mental syndrome in the elderly patient, in Geriatric Psychiatry, edited by Bellak L, Karasu TB. New York, Grune and Stratton, 1976Google Scholar

50. Galloway P, Sahgal A, McKeith I, et al: Visual pattern recognition memory and learning deficits in senile dementia of Alzheimer and Lewy body types. Dementia 1992; 3:101–107Google Scholar

51. Sahgal A, Galloway P, McKeith I, et al: Matching-to-sample deficits in patients with senile dementias of the Alzheimer and Lewy body types. Arch Neurol 1992; 49:1043–1046Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Zola-Morgan S, Squire L: Memory impairment in monkeys following lesions of the hippocampus. Behav Neurosci 1986; 100:155–160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Lennox G, Lowe J, Godwin-Austen R, et al: Diffuse Lewy body disease: an important differential diagnosis in dementia with extrapyramidal features. Prog Clin Biol Res 1989; 317:121–130Medline, Google Scholar

54. Hakim A, Mathieson G: Dementia in Parkinson's disease: a neuropathologic study. Neurology 1979; 29:1209–1214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Perry E, Curtis M, Dick D, et al: Cholinergic correlates of cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: comparisons with Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985; 48:413–421Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Rogers J, Brogan D, Mirra S: The nucleus basalis of Meynert in neurological disease: a quantitative morphological study. Ann Neurol 1985; 17:163–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Byrne E, Lennox G, Lowe J, et al: Diffuse Lewy body disease: the clinical features. Adv Neurol 1990; 53:283–286Medline, Google Scholar

58. Gibb W, Esiri M, Lees A: Clinical and pathological features of diffuse cortical Lewy body disease (Lewy body dementia). Brain 1987; 110:1131–1153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Louis E, Klatka L, Liu Y, et al: Comparison of extrapyramidal features in 31 pathologically confirmed cases of diffuse Lewy body disease and 34 pathologically confirmed cases of Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1997; 48:376–380Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Louis E, Fahn S: Pathologically diagnosed diffuse Lewy body disease and Parkinson's disease: do the parkinsonian features differ? Adv Neurol 1996; 69:311–314Google Scholar

61. Rajput A, Pahwa R, Pahwa P, et al: Prognostic significance of the onset mode in parkinsonism. Neurology 1993; 43:829–840Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Clark R, Lord S, Webster I: Clinical parameters associated with falls in an elderly population. Gerontology 1993; 39:117–123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Van Dijk P, Meulenberg O, van de Sande H, et al: Falls in dementia patients. Gerontologist 1993; 33:200–204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Louis E, Goldman J, Powers J, et al: Parkinsonism features of eight pathologically diagnosed cases of diffuse Lewy body disease. Mov Disord 1995; 10:188–194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Filley C: Neuropsychiatric features of Lewy body disease. Brain Cogn 1995; 28:229–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Klatka L, Schiffer RB, Powers J, et al: Incorrect diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:35–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Mark M, Dickson D, Sage J, et al: The clinicopathologic spectrum of Lewy body disease. Adv Neurol 1996; 69:315–318Medline, Google Scholar

68. Sima A, Clark A, Sternberger N, et al: Lewy body dementia without Alzheimer changes. Can J Neurol Sci 1986; 13:490–497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Mann DMA, Snowden JS: The topographic distribution of brain atrophy in cortical Lewy body disease: comparison with Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol 1995; 89:178–183Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Byrne E, Lennox G, Lowe J, et al: Dementia associated with cortical Lewy bodies: proposed clinical diagnostic criteria. Dementia 1991; 2:283–284Google Scholar

71. Wilcock G, Scott M: Tacrine for senile dementia of Alzheimer's or Lewy body type (letter). Lancet 1994; 344:544Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Summers W, Majorski L, Marsh G, et al: Oral tetrahydroaminoacridine in long term treatment of senile dementia, Alzheimer type. N Engl J Med 1986; 315:1241–1245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Chacko R, Hurley R, Jankovic J: Clozapine use in diffuse Lewy body disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 5:206–208Link, Google Scholar