Pharmacologic Efficacy in Neuropsychiatry

Abstract

Psychiatric disorders frequently compound the disability and complicate the management of neurologic conditions. These disorders result in increased morbidity for the person afflicted, stress for the caregiver, and financial burden. This study reviews the randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pharmacologic treatment trials of psychosis, depression, anxiety, and agitation in neurologic conditions from 1966 to 1998. Ten studies involving psychosis, 13 involving depression, and 20 involving anxiety-agitation meeting the committee's criteria were identified. Relatively few randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pharmacologic treatment trials of psychiatric disorders complicating neurologic disease have been conducted. These trials do not strongly support one specific pharmacologic approach to treatment. Further study of newer psychotropic agents, augmentation strategies, and novel use of other agents may help improve the treatment of psychiatric disorders observed in patients with neurologic disease.

Neurologic disorders are complicated frequently by psychiatric disturbances, especially psychosis, depression, anxiety, and agitation. The frequency with which psychosis occurs ranges from 10% to 50% in patients with Alzheimer's disease and 3% to 30% in patients with Parkinson's disease.1 Likewise, the coexistence of depression has been extensively studied in such disorders as Alzheimer's dementia, stroke, and Parkinson's disease. However, the frequency of depression in these disorders varies widely. From 0% to 50% of patients with Alzheimer's disease, 20% to 50% of patients following a stroke, and more than 50% of patients with Parkinson's disease will develop a depression syndrome.1 Anxiety and agitation are often vague and ill defined; consequently, it has been very difficult to determine the frequency of these conditions in populations with concurrent neurologic disease.

Psychosis, depression, and agitation have considerable impact on functional status, independence, and quality of life for both the affected individual and the caregiver. Nutritional status of the person can be affected by the presence of these disorders; withdrawal and inactivity may result in muscle wasting and weakness as well as increased risk of aspiration pneumonia and pulmonary emboli. The excess disability associated with neuropsychiatric illness affects the underlying neurologic condition, resulting in poorer outcomes and increased morbidity and mortality.

The development of neuropsychiatric problems adds to caregiver stress. These psychiatric symptoms are often more overwhelming and disabling for the caregiver than the original problems associated with neurologic impairment. In fact, one study of people with dementia found that the caregiver burden associated with psychiatric disturbances is a stronger predictor of nursing home placement than dementia severity.2 Consequently, these problems add to the increasing cost of caring for neurologically compromised people.

Management of these conditions varies considerably. Few placebo-controlled trials have been conducted on the treatment of psychosis, depression, anxiety, and agitation in neurologically impaired individuals. This report reviews all available double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of pharmacological interventions for the management of psychosis, depression, anxiety, and agitation in people with underlying neurologic disorders in order to provide a basis for the development of meaningful research initiatives for treatment of psychiatric symptoms in neurologic patients.

METHODS

We conducted an extensive review of the existing literature on treatment studies published from January 1966 to March 1998. This review included articles published in English indexed in medline, Psychinfo, and embase/Excerpta Medica. The papers of interest were double-blind placebo-controlled pharmacologic treatment trials for psychosis, depression, anxiety, or agitation in patients with underlying neurologic diseases. The neurologic disorders included, but were not limited to, dementia (of any type), Parkinson's disease, stroke, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Huntington's disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–related central nervous system (CNS) disease, mental retardation, brain injury, and CNS disease.

Search strategies for each psychiatric condition were individually designed for optimal capture of references pertaining to the specific target condition of psychosis, depression, anxiety, or agitation. A uniform strategy of using the same terms was employed between searches to retrieve references pertaining to specific neurological diseases. Because of differences in computerized literature database indexing and search strategies, different techniques can elicit different reference retrieval patterns. Articles are not always uniformly indexed within a specific database, nor between different databases. Despite this limitation, we detected and reviewed between 300 and 1,500 citations for each of the four psychiatric conditions identified.

RESULTS

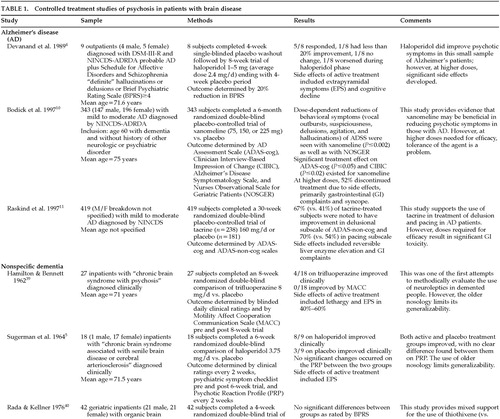

Psychosis

Ten studies examining the treatment of psychosis in patients with brain disease met the inclusion criteria for this study (Table 1A and Table 1B). Nine studies evaluated the use of pharmacologic agents in people with dementia. The remaining study3 evaluated the use of clozapine in drug-induced psychosis in patients with Parkinson's disease being treated with dopamine agonists.

Neuroleptics including haloperidol4–6 and thioridazine7 have been shown to be superior to placebo in treating various psychotic symptoms in demented people. However, many of the older studies lack clear diagnostic criteria in determining their patient population. This limits the generalizability of the conclusions. Of trials reporting degrees of improvement, many reported only a modest advantage of active agent over placebo. Side effects were common, especially extrapyramidal symptoms, and were often more problematic than the original psychotic symptoms. Agitation, “noisiness,” “restiveness,” “overactivity,” and incontinence have worsened sometimes in subjects being treated with neuroleptics.8 Consequently, the efficacy of neuroleptics in reducing psychotic symptoms does not always translate into improvements in patients' functional capacity.9

Although “atypical” neuroleptics are being treated as equal or superior to “traditional” neuroleptics with fewer side effects, only one placebo-controlled trial3 was found. In this study, clozapine was used in patients with Parkinson's disease and psychosis. Half the subjects withdrew from the study because of significant side effects, and the other half exhibited a worsening of their parkinsonian symptoms.

Novel approaches to treating psychotic symptoms, making use of a knowledge of the pathophysiology of the underlying neurologic disorders, have been reported. Two recent studies10,11 have studied muscarinic receptor agonists and cholinesterase inhibitors, respectively, in the treatment of psychiatric disturbances in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Unfortunately, the doses necessary to produce benefit also produced significant side effects, thereby limiting their clinical utility.

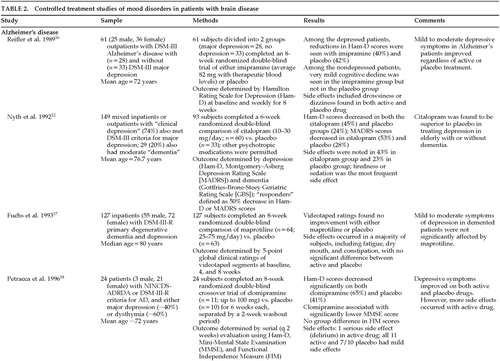

Depression

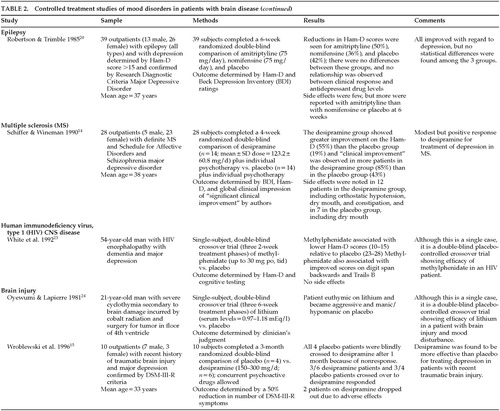

Thirteen studies were found on the treatment of mood disorders (depression) in individuals with brain diseases that met the inclusion criteria (Table 2A, Table 2B, and Table 2C). Although depression is commonly found in patients with neurologic disorders, the treatment trial for any one group was very small, making it difficult to endorse any one approach to treating depression in these populations.

Only three studies with more than 10 subjects reported significant improvement in active drug over placebo in the treatment of depression in neurologically ill people. These included the use of citalopram in patients with depression and Alzheimer's disease12 and with poststroke depression,13 and use of desipramine in patients with depression and multiple sclerosis.14 In a very small study of 10 patients, desipramine appeared to be superior to placebo in treating depression in brain-injured subjects; however, 2 of the subjects on active treatment dropped out.15

Nearly half of the trials reported that active treatment was no better than placebo. These studies examined the use of imipramine,16 maprotiline,17 or clomipramine18 for depression in patients with Alzheimer's disease, trazodone19 for patients with poststroke depression, and amitriptyline or nomifensine20 in patients with depression and epilepsy. Beneficial effects of nortriptyline in patients with Parkinson's disease21 were complicated by significant problems with orthostatic hypotension. Likewise, delirium and cardiovascular morbidity occurred in patients taking nortriptyline for poststroke depression.22

Two single-subject reports were found that used double-blind, placebo-controlled methodology. Methyl[chphenidate was found to be superior to placebo in treating depressive symptoms in a person with HIV disease,23 and lithium was superior to placebo in treating depressive symptoms in subjects with “mood swings” following radiation and surgery for treatment of CNS tumor.24

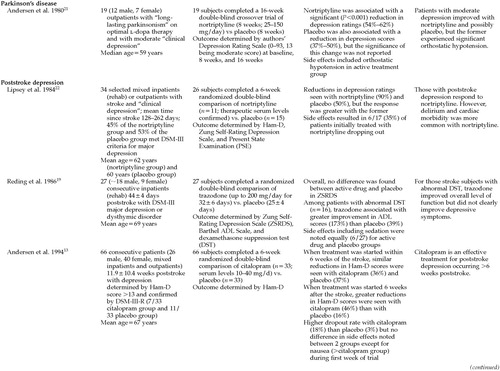

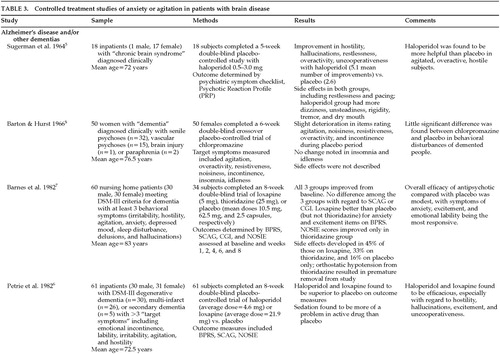

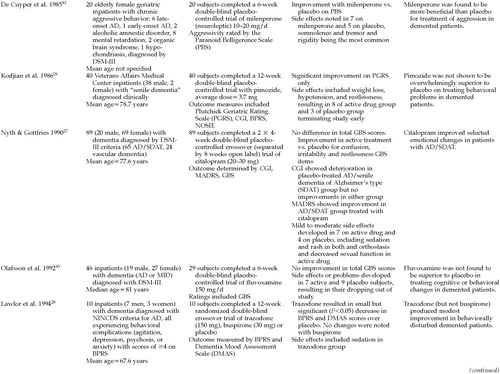

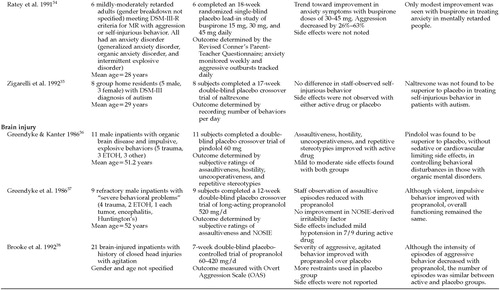

Anxiety and Agitation

Twenty studies of the treatment of anxiety and agitation in patients with brain disease met criteria for inclusion in the study (Table 3A, Table 3B, Table 3C, and Table 3D). The symptoms of “anxiety and agitation” are not well defined, and uniform measures to assess change and ultimate outcome are lacking. Therefore, it is difficult to generalize the findings of these studies in this category. Because of this heterogeneity, a variety of agents, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, anxiolytics, beta-blockers, and naltrexone have been studied in the treatment of “anxiety and agitation” in the neurologically ill.

Antipsychotics were the most frequently studied agents for treating anxiety and agitation in individuals with dementia. Haloperidol, loxapine, and thiothixene appear to be efficacious for some symptoms.5–7,25 However, chlorpromazine,8 thioridazine,7 and pimozide26 were reported to be no more efficacious than placebo. Citalopram27 and trazodone28 were similar to placebo. Carbamazepine treatment gave mixed results.29,30

In those with mental retardation, anxiety and agitation appear to respond to an investigational benzodiazepine,31 an experimental antipsychotic,32 and lithium.33 Buspirone produced minimal effects,34 and naltrexone was no better than placebo.35 Only beta-blockers, pindolol,36 and propranolol37,38 have been studied in brain-injured people. Although both agents produced some benefit, propranolol appears to have only limited usefulness because of its significant side effects.

DISCUSSION

Very few randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pharmacological trials are available to guide the clinician when treating psychosis, depression, or anxiety-agitation in the context of a neurological disorder. Randomized placebo-controlled studies are essential to advance our understanding of the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders in patients with neurologic disease.

Many of the existing double-blind studies show a surprisingly robust placebo effect. This finding suggests that anecdotal observations of improvement following administration of specific agents will frequently be documenting a placebo-related effect rather than necessarily establishing a specific biochemical or pharmacologic effect. Treatment effects size also tends to vary among patients with neurological illnesses of different severities or in different stages, and the effect size may not be predictable on the basis of small samples or open-label studies. Side effects may be more common in neurologically ill patients than in patients with psychiatric disturbances without an associated neurologic disease, and treatment of a larger number of patients with active agents and placebo will help establish the spectrum of potential side effects.

Neuropsychiatric disturbances with neurologic illness may respond substantially differently from the same type of psychiatric disorder in patients without neurologic illness. For example, the cholinergic deficiency in Alzheimer's disease may alter the effect of standard or novel antipsychotics in the treatment of psychosis in this disease. Similarly, serotonergic abnormalities that follow cerebrovascular insult may alter the response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of depression. Thus, randomized, controlled studies should be conducted in patients with clearly defined neurologic illness to establish the utility of psychotropic medications in these special populations.

Conducting double-blind placebo-controlled studies in patients with neuropsychiatric disorders and neurological illnesses poses difficult challenges. Patients frequently have comorbid conditions (e.g., hypertension, cardiac or renal disease) that may complicate participation in blinded trials. Neurologically ill patients often require treatment with medications that may interact with the study agent (antihypertensives, dopaminergic agents for Parkinson's disease, or cholinergic agents for Alzheimer's disease). The application of diagnostic criteria (e.g., for depression) derived from populations of patients without neurological illness may be difficult, and current standard assessment and outcome tools are often inadequate in detecting changes that affect a patient's functional status and quality of life.

Despite these challenges, there must be a standardization of diagnostic inclusion and exclusion criteria and agreement on the rating scales and primary outcome measures to be used. In order to estimate the sample size necessary to determine a treatment effect, the placebo response rate must be determined for the psychiatric problem in each disorder. It is not wise to lump together patients with different neurological disorders who have the same psychiatric symptoms. The measurement of side effects in these vulnerable populations is just as important as the determination of the reduction in psychiatric symptoms. Attaining results that are meaningful to clinicians will require conducting class-to-class comparisons of medication, such as high-potency versus atypical neuroleptics for the treatment of psychosis in dementia, in addition to comparisons with placebo.

The population of neurologically ill patients with specific neuropsychiatric syndromes is relatively small, requiring expensive multicenter investigations to establish reasonable sample sizes. The relatively small size of the populations in question also makes conducting such studies of less financial interest to pharmaceutical companies seeking large markets. However, a number of large-scale industry-sponsored controlled trials are already under way for psychiatric symptoms in neurological patients. Some disorders, such as psychosis in dementia, involve large patient groups, which are attractive for pharmaceutical companies to study. These multicenter trials require a large sample size to demonstrate a treatment effect. For example, one placebo-controlled trial of a neuroleptic for the treatment of psychosis in dementia will require a sample of 360 patients to reach statistical significance. These trials are expensive to conduct, but they are essential for providing the scientific foundation to move the field of neuropsychiatry forward.

The American Neuropsychiatric Association and its members can play an important role in fostering controlled treatment trials for neuropsychiatric conditions. These efforts might include the following:

| 1. | Developing a consensus position on the most effective outcome measures in various disorders. | ||||

| 2. | Developing research consortia for studies in specific populations, such as the Huntington's Study Group. | ||||

| 3. | Working with the pharmaceutical industry and self-help/advocacy groups to design and implement these trials. | ||||

| 4. | Working with third-party payers to include a neuropsychiatric assessment as part of the critical pathway in neurological and psychiatric patients. | ||||

| 5. | Developing methods of assessing the fiscal impact of behavioral disorders in neurological patients. | ||||

| 6. | Using small-scale studies such as N-of-1 designs with blinded raters to establish preliminary information for treatment of some disorders. | ||||

In conclusion, people afflicted with neurologic disorders frequently develop secondary behavioral disturbances, many of which are psychiatric disorders. These disturbances result in considerable disability, caregiver stress, and financial burden. It is imperative to assess interventions—such as the use of newer psychotropic medication and the use of augmenting strategies—that may be beneficial in relieving the suffering of those with neurologic disease who are experiencing psychiatric problems.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 Coffey E, Cummings J: Textbook of Geriatric Neuropsychiatry. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

2 Colerick EJ, George LK: Predictors of institutionalization among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1986; 34:493–498Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Wolters EC, Hurwitz TA, Mak E, et al: Clozapine in the treatment of parkinsonian patients with dopaminomimetic psychosis. Neurology 1990; 40:832–834Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Devanand DP, Sackeim HA, Brown RP, et al: A pilot study of haloperidol treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbance in Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol 1989; 46:854–857Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Sugerman AA, Williams BH, Adlerstein AM: Haloperidol in the psychiatric disorders of old age. Am J Psychiatry 1964; 120:1190–1192Google Scholar

6 Petrie WM, Ban TA, Berney S, et al: Loxapine in psychogeriatrics: a placebo- and standard-controlled clinical investigation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1982; 2:122–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Barnes R, Veith R, Okimoto J, et al: Efficacy of antipsychotic medications in behaviorally disturbed dementia patients. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139:1170–1174Google Scholar

8 Barton R, Hurst L: Unnecessary use of tranquilizers in elderly patients. Br J Psychiatry 1966; 112:989–990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Breier A, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, et al: National Institute of Mental Health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia: prognosis and predictors of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:239–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Bodick NC, Offen WW, Levey AI, et al: Effects of xanomeline, a selective muscarinic receptor agonist, on cognitive function and behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1997; 54:465–473Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Raskind MA, Sadowsky CH, Sigmund WR, et al: Effect of tacrine on language, praxis, and noncognitive behavioral problems in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1997; 54:836–840Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Nyth AL, Gottfries CG, Lyby K, et al: A controlled multicenter clinical study of citalopram and placebo in elderly depressed patients with and without concomitant dementia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 86:138–145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Andersen G, Vestergaard K, Lauritzen L: Effective treatment of poststroke depression with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram. Stroke 1994; 25:1099–1104Google Scholar

14 Schiffer RB, Wineman NM: Antidepressant pharmacology of depression associated with multiple sclerosis. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1493–1497Google Scholar

15 Wroblewski BA, Joseph AB, Cornblatt RR: Antidepressant pharmacotherapy and the treatment of depression in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a controlled, prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:582–587Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Reifler BV, Teri L, Raskind M, et al: Double-blind trial of imipramine in Alzheimer's disease patients with and without depression. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:45–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Fuchs A, Hehnke U, Erhart C, et al: Video rating analysis of effect of maprotiline in patients with dementia and depression. Pharmacopsychiatry 1993; 26:37–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Petracca G, Tesón A, Chemerinski E, et al: A double-blind placebo-controlled study of clomipramine in depressed patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:270–275Link, Google Scholar

19 Reding MJ, Orto LA, Winter SW, et al: Antidepressant therapy after stroke. Arch Neurol 1986; 763–765Google Scholar

20 Robertson MM, Trimble MR: The treatment of depression in patients with epilepsy: a double-blind trial. J Affect Disord 1985; 9:127–136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Andersen J, Aabro E, Gulmann N, et al: Anti-depressive treatment in Parkinson's disease: a controlled trial of the effect of nortriptyline in patients with Parkinson's disease treated with l-dopa. Acta Neurol Scand 1980; 62:210–219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Lipsey JR, Robinson RG, Pearlson GD, et al: Nortriptyline treatment of post-stroke depression: a double-blind study. Lancet 1984; 8372:297–300Crossref, Google Scholar

23 White JC, Christensen JF, Singer CM: Methylphenidate as a treatment for depression in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: an n-of-1 trial. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53:153–156Medline, Google Scholar

24 Oyewumi LK, Lapierre YD: Efficacy of lithium in treating mood disorder occurring after brain stem injury. Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138:110–112Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Finkel S, Lyons JS, Anderson RL, et al: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of thiothixene in agitated, demented nursing home residents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1995;10:129–136Google Scholar

26 Kodjian A, Barriaga C, Turcot G, et al: Double-blind study of pimozide in senile dementia patients. Current Therapeutic Research 1986; 40:694–701Google Scholar

27 Nyth L, Gottfries CG: Clinical efficacy of citalopram in treatment of emotional disturbances in dementia disorders: a Nordic multi-center trial. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:894–901Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Lawlor BA, Radcliff J, Molchan SE, et al: A pilot placebo-controlled study of trazodone and buspirone in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1994; 9:55–59Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Tariot PN, Erb R, Leibovici A, et al: Carbamazepine treatment of agitation in nursing home patients with dementia: a preliminary study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42:1160–1166Google Scholar

30 Tariot PN, Erb R, Podgorski CA, et al: Efficacy and tolerability of carbamazepine for agitation and aggression in dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:54–61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Albert JM, Elie R, Cooper SF, et al: Efficacy of SCH-12679 in the management of aggressive mental retardates. Current Therapeutic Research 1977; 21:786–795Google Scholar

32 Lynch DM, Eliatamby CLS, Anderson AA: Pipothiazine palmitate in the management of aggressive mentally handicapped patients. Br J Psychiatry 1985;146:525–529Google Scholar

33 Craft M, Ismail IA, Krishnamurti D, et al: Lithium in the treatment of aggression in mentally handicapped patients: a double-blind trial. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150:685–689Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Ratey J, Sovner R, Parks A, et al: Buspirone treatment of aggression and anxiety in mentally retarded patients: a multiple baseline, placebo lead-in study. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:159–162Medline, Google Scholar

35 Zigarelli G, Ellman G, Hem A, et al: Clinical effects of naltrexone on autistic behavior. Am J Ment Retard 1992; 97:57–63Medline, Google Scholar

36 Greendyke RM, Kanter DR: Therapeutic effects of pindolol on behavioral disturbances associated with organic brain disease: a double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 1986; 47:423–426Medline, Google Scholar

37 Greendyke RM, Kanter DR, Schuster DB, et al: Propranolol treatment of assaultive patients with organic brain disease. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:290–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Brooke MM, Patterson DR, Questad KA, et al: The treatment of agitation during initial hospitalization after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992; 73:917–921Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 Hamilton LD, Bennett JL: The use of trifluoperazine in geriatric patients with chronic brain syndrome. J Am Geriatr Soc 1962; 10:140–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 Rada RT, Kellner R: Thiothixene in the treatment of geriatric patients with chronic organic brain syndrome. J Am Geriatr Soc 1976; 24:105–107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Gotestam KG, Ljunghall S, Olsson B: A double-blind comparison of the effects of haloperidol and cis(z)-clopenthixol in senile dementia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1981; 294:46–53Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 De Cuyper H, van Praag HM, Verstraeten D: The effect of milenperone on the aggressive behavior of psychogeriatric patients. Biol Psychiatry 1985; 13:1–6Google Scholar

43 Olafsson K, Jorgensen S, Jensen HV, et al: Fluvoxamine in the treatment of demented elderly patients: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992; 85:453–456Google Scholar