Attitudes Toward Neurosurgical Procedures for Parkinson's Disease and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Abstract

Similar neurosurgical procedures exist for Parkinson's disease (PD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Because PD is seen as a brain disease and OCD as a disease of the mind, neurologists and psychiatrists may be more aware of and more optimistic toward neurosurgery for PD than for OCD. A questionnaire was sent to randomized American Psychiatric Association and American Academy of Neurology members, and 569 of 1,188 eligible members (47.9%) responded. Some 82.8% of the psychiatrists and 27.4% of the neurologists were aware of neurosurgical procedures for OCD, whereas 84.7% of psychiatrists and 99.4% of neurologists were aware of neurosurgery for PD (P<0.001). Of psychiatrists, 74.1% would refer appropriate patients for OCD neurosurgery, 67.4% for PD neurosurgery (P=0.15); of neurologists, 25.6% would refer for OCD, 94.3% for PD (P<0.001). Specialty affected willingness to refer for OCD neurosurgery. Specialty and degree of contact with neurosurgeons affected willingness to refer for PD neurosurgery. There is poor physician awareness of neurosurgical options for OCD compared with PD, as well as a risk–benefit bias against OCD surgery by the neurologists surveyed.

Over the past quarter-century, the advent of new biologic treatments has dramatically improved psychiatry's ability to treat safely and effectively such conditions as major depression, manic-depressive illness, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Nonetheless, only a small percentage of patients who potentially could have benefited have received these new treatments.1,2 Among the explanations posited for the large percentage of the mentally ill who go untreated are negative attitudes and deficient awareness of available treatments—both on the part of patients and physicians.3

Many investigators point to the historical stigmatization of the mentally ill as the basis of this persistently poor understanding by patients and professionals. Such misunderstanding may be partly responsible for the failure to recognize the prominent role of brain dysfunction in the pathogenesis of these conditions.4 The hypothesis that the mind and the brain are separate—termed cartesian dualism after the writings of Descartes—has been used to explain, for example, why people with seizure disorders and Parkinson's disease (PD) were mistreated by society until the neurologic etiologies of these conditions became recognized by medicine and accepted by the general public.5

Today, PD is conceptualized as a neurodegenerative disorder and is usually treated by neurologists, whereas OCD is a considered a mental illness and is usually treated by psychiatrists and psychologists. However, the two illnesses have much in common: both can lead to a marked disability;6,7 both have been linked to alterations in brain neurotransmitters8–12 (although it should be noted that the pathophysiologic correlation with dopaminergic deficits in PD is stronger and better established than the serotonergic abnormalities in OCD); and although both respond to pharmacologic interventions, many patients with the most severe forms of both illnesses require further intervention.

For patients in both conditions who fail to respond to standard pharmacological regimens, neurosurgical procedures may afford substantial relief. Although PD neurosurgery and OCD neurosurgery are relatively equivalent in operative technique, associated morbidity, and therapeutic outcome,13–18 the former has widespread use,19 while the latter is rarely performed in the United States.17 In this article we investigate the awareness of and attitudes toward neurosurgical procedures for PD and OCD among neurologists and psychiatrists. In particular, we compare the pallidotomy procedure for PD with the anterior capsulotomy procedure for OCD, although there are several other procedures in use for OCD, such as the cingulotomy, limbic leukotomy, and subcaudate tractotomy. The authors' expectation is that the conventional conceptualization of PD as a brain disorder will result in greater awareness of and optimism about neurosurgical procedures for PD among all respondents, when compared with OCD, because the latter is still generally regarded as an illness of the mind. Our hypothesis is that such a discrepancy, if discovered, would lend support to previous contentions that prioritizing mind over brain in the conceptualization of mental illness results in inadequate treatment.5

METHODS

Sample

The data used in this study were derived from a survey of a stratified random sample of 3,000 individuals conducted between January 1997 and April 1997. Stratification resulted in 1,000 individuals being included as U.S. members of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and 1,000 being included as U.S. members of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN). The AAN has more than 14,000 U.S. members; 1,000 names were randomly selected with additional geographic and subspecialty stratification. The APA has more than 41,000 U.S. members; 1,000 names were randomly selected with stratification by zip code.

Questionnaire Design, Administration, and Analytic Techniques

We developed two self-administered, anonymous questionnaires that included sections on demographic characteristics, professional experiences with PD and OCD, and knowledge and attitudes toward stereotactic neurosurgery for PD and OCD (survey instrument available on request). The APA and AAN surveys were identical except for the ordering of questions: the AAN surveys addressed pallidotomy prior to anterior capsulotomy. Most response choices were dichotomous (yes/no). The survey packet included a cover letter (including information on informed consent), a copy of the questionnaire, and a prepaid return envelope. The questionnaire and study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine. The initial survey and follow-up were conducted by mail and administered by the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy and the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences of Baylor College of Medicine.

After 1 month, APA and AAN nonrespondents were mailed an additional survey and cover letter requesting participation. After a second month, we attempted to contact every fourth remaining nonrespondent from the APA and AAN lists by telephone, requesting their fax numbers to send another survey to those interested in completing it. This intensive data-collecting effort revealed errors in the original membership listings. Of the 2,000 APA and AAN members in our initial sample, 812 were declared ineligible. Respondents were determined to be ineligible because they were duplicate listings (those who were included in more than one sample), were deceased or retired, were non-M.D.s, failed to meet the deadline, or could not be located (those persons for whom no return mailing was received and who could not be located by telephone follow-up). Of the remaining, eligible 1,188 APA and AAN members, 569 returned valid questionnaires, yielding an overall response rate of 47.9%.

The survey data set was managed by using dBASE software and was analyzed with standard statistical techniques found in the SPSS software. Differences in proportions were tested with two sample proportions tests. Chi-square tests were applied to multilevel categorical data. Logistic regression was used for multivariate analyses, with relaxed statistical criteria for retaining variables in the model (P<0.1). Because of possible bias from multiple comparisons, statistical significance was set at the more conservative P<0.001 level.

Variables

Several dependent variables were used to measure attitudes and knowledge of stereotactic neurosurgical procedures. The first dependent variable (awareness) indicated the extent to which psychiatrists and neurologists were aware of neurosurgical procedures for PD and OCD. This parameter was derived from the following questions, which followed a brief introductory paragraph describing stereotactic pallidotomy and anterior capsulotomy: “I am aware of neurosurgical procedures for Parkinson's disease” and “I am aware of neurosurgical procedures for OCD.” The dichotomous response categories for each item were “yes” and “no.”

A second dependent variable (future referral) reflected respondents' plans to refer a patient with disabling PD for pallidotomy and a patient with disabling OCD for anterior capsulotomy. This parameter was measured through the following questions: “I would refer a patient with disabling Parkinson's disease refractory to medications and other interventions for pallidotomy” and “I would refer a patient with disabling OCD refractory to medications and psychosocial interventions for anterior capsulotomy.” An additional, related question began with “I believe colleagues in my state would refer….” The valid responses were again dichotomous, affirmative versus otherwise.

A third dependent variable (assessment) reflected respondents' evaluation of each stereotactic procedure. This variable was derived from the following question: “I consider pallidotomy [question repeated for anterior capsulotomy] to be: an experimental procedure, a medically accepted procedure, I don't know.” A trichotomous coding scheme was allowed here to better reflect respondents' knowledge.

For the APA and AAN surveys, this study investigated the potential association of three groups of independent variables on awareness, future referral patterns, and assessment of stereotactic neurosurgery: personal characteristics, practice patterns, and geography.

Personal characteristics included gender, race, age, academic affiliation (full-time faculty, volunteer or part-time faculty, resident/fellow, none), and board status (certified, eligible, other).

Two variables related to practice patterns: 1) number of patients seen per month with the diagnosis of PD and OCD and 2) degree of professional contact with neurosurgeons. To measure number of patients, the survey asked: “How many patients per month do you see with the diagnosis of Parkinson's [and again for OCD],” with options of 0–1, 2–5, 6–10, and >10 patients per month for both diagnoses. To gauge degree of contact with neurosurgeons, the survey asked: “My degree of professional contact with neurosurgeons is: none, rare, occasional, frequent, daily.”

Geography constituted the third category of independent variables. Respondents were asked to use the two-letter postal code of the state where they practice. We hypothesized that those physicians practicing in Rhode Island or Massachusetts would be more likely to be aware of OCD neurosurgery because of geographic proximity to stereotactic neurosurgery centers.

RESULTS

Physician Demographics and Practice Patterns

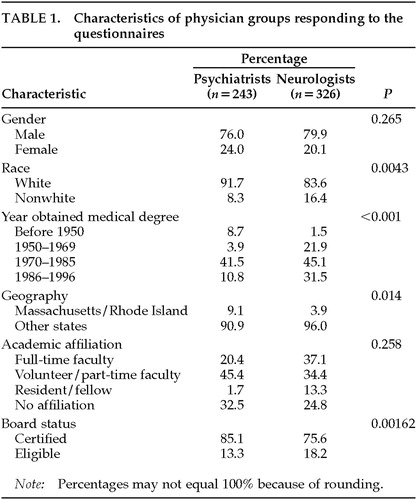

Of the 1,188 eligible APA and AAN members surveyed, 569 valid physician questionnaires (47.9%) were returned and evaluated (243 from psychiatrists and 326 from neurologists). There were no significant differences in the two physician groups in terms of gender, race, geography, or academic affiliation. Neurologists were significantly younger than psychiatrists (P<0.001). Board status had statistical significance (P=0.00162), although this was likely a secondary effect of age differences (Table 1). Compared with the AAN and APA memberships at large, our sample was representative for both groups in terms of gender, geographic distribution, ethnicity, and academic affiliation, but not for age distribution for the neurologists20 or extent of board certification for the psychiatrists (85.1% in our sample vs. 55.3% nationally; personal communication with APA Office of Membership).

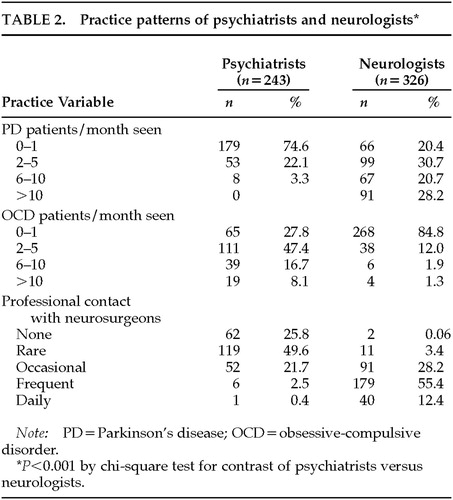

There were notable differences in practice patterns between the surveyed psychiatrists and neurologists (Table 2). As would be expected, a significantly greater proportion of practicing neurologists than psychiatrists saw a moderate to high number of PD patients per month (6 or greater; P<0.001). Likewise, a significantly greater proportion of psychiatrists than neurologists saw a moderate to high number of OCD patients per month (P<0.001). Only 3.2% of neurologists (n=10/312) saw 6 or more OCD patients per month, whereas only 3.3% of psychiatrists (n=8/242) saw 6 or more PD patients per month. For degree of professional contact with neurosurgeons, again there were significant differences: neurologists were much more likely to have a high level of contact than psychiatrists (P<0.001). Notably, 75.4% of psychiatrists (n=181/240) reported no or rare professional contact with neurosurgeons, while only 3.5% of neurologists (n=13/323) reported this low level of contact.

Physician Responses to Questionnaire

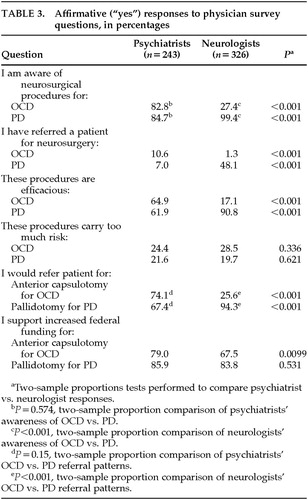

In all, 82.8% of psychiatrists (n=192/232) were aware of neurosurgical procedures for OCD, compared with 27.4% of neurologists (n=86/314; P<0.001; Table 3). Regarding pallidotomy for PD, 84.7% of psychiatrists (n=183/216) were aware of the procedure, compared with 99.4% of neurologists (n=312; P<0.001). In comparing psychiatrists' and neurologists' respective awareness of OCD versus PD neurosurgery, there were no significant differences for psychiatrists (P=0.574), but neurologists were significantly more likely to be aware of neurosurgical procedures for PD (P<0.001) than for OCD. Twenty-five psychiatrists (10.6%) have referred patients for OCD surgery, while 154 neurologists (48.1%) have referred patients for PD surgery (both P<0.001). Significantly more psychiatrists than neurologists (64.9% vs. 17.1%, P<0.001) regarded neurosurgical procedures for OCD as efficacious; conversely, significantly more neurologists than psychiatrists (90.8% vs. 61.9%, P<0.001) considered PD surgery efficacious relative to OCD surgery. The clear majority of both physician groups felt that neurosurgical procedures for OCD or PD did not carry too much risk, since all responses in this category received less than 30% affirmative responses, with nonsignificant P-values between groups.

In addition, 74.1% of psychiatrists (n=146/197) would refer an appropriate OCD patient for anterior capsulotomy, and 67.4% (n=122/181) were willing to refer an appropriate PD patient for pallidotomy (P=0.15). For neurologists, 25.6% (n=56/218) would refer an OCD patient for neurosurgery, while 94.3% (n=297/314) would refer a PD patient for pallidotomy (P<0.001). There were significant specialty differences between psychiatrists and neurologists (P<0.001) for willingness to refer an appropriate patient for these procedures. There was also strong support from both psychiatrists and neurologists for increased federal funding for both OCD and PD neurosurgery.

A large majority of both psychiatrists and neurologists felt that their fund of knowledge for anterior capsulotomy for OCD was inadequate or minimally adequate (89.3% and 96.8%, respectively). Similarly for pallidotomy for PD, psychiatrists overwhelmingly felt that their fund of knowledge was inadequate or minimally adequate (87.2%), although fewer than one-half of the neurologists (49.2%) felt they had a deficient knowledge base regarding pallidotomy for PD. For anterior capsulotomy for OCD, 26.9% of psychiatrists (n=63/234) considered it an experimental procedure, 22.2% (n=52/234) considered it medically accepted, and 50.9% (n=119/234) said they did not know. Neurologists more commonly felt it was an experimental procedure rather than a medically accepted procedure (n=104/287, 36.2%, vs. n=9/290, 3.1%, P<0.01), although 60.6% (n=174/287) said they did not know. In assessing pallidotomy for PD, there was no significant difference between psychiatrists who thought the procedure was experimental and those who thought it was medically accepted (22.1% vs. 29.6%, P=0.116). Neurologists significantly felt that pallidotomy was a medically accepted rather than an experimental procedure (65.3% vs. 27.1%, P<0.0001).

Relationship of Independent Variables to Awareness, Willingness to Refer, and Assessment of Procedure

Univariate Analysis:

Univariate analysis was conducted for both psychiatrists and neurologists to see if any physician-based independent variables were positively associated with awareness, willingness to refer, or assessment of neurosurgical procedures for OCD and PD. In assessing awareness of anterior capsulotomy for OCD, both psychiatrists and neurologists practicing in Massachusetts and Rhode Island were significantly more likely to be aware of anterior capsulotomy for OCD (P<0.001, Mantel-Haenszel test for linear association), but the relevant subgroup was so small (n=30) that the finding is questionable. Relevant subgroup analyses were not performed to determine the percentage of these 30 physicians who have referred patients for OCD neurosurgery. Also, younger age of physician (P<0.001) was associated with awareness of OCD neurosurgery, but not with awareness of PD neurosurgery (P= 0.9044, Mantel-Haenszel test). None of the other independent variables, notably number of patients seen with the disease, were significantly correlated with physician awareness of either procedure.

Univariate analysis revealed that physician contact with neurosurgeons (P<0.0001) was associated with willingness to refer a patient for anterior capsulotomy for OCD; however, with psychiatrists and neurologists tested independently, no such correlation could be drawn (P=0.4084 and P=0.2420, respectively). Ethnicity also was associated with willingness to refer for OCD neurosurgery (P=0.008); however, we suspect artifact due to the low frequency of nonwhite respondents. Univariate analysis revealed no effect of geography, gender, age, academic affiliation, board status, or number of patients seen per month on willingness to refer for either anterior capsulotomy for OCD or pallidotomy for PD.

Regarding the assessment dependent variable, univariate analysis revealed no association of independent variables with the assessment of pallidotomy for PD or anterior capsulotomy for OCD as medically accepted versus experimental.

Multivariate Analysis:

To examine further the relationship of independent variables to our measures of willingness to refer for OCD and PD neurosurgery, we performed backward stepwise logistic regressions with somewhat liberal criteria for retaining variables in the model (P<0.1).

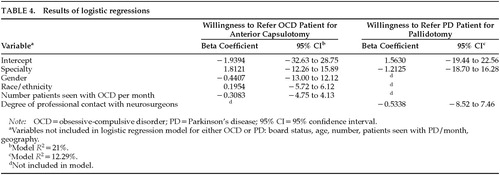

Specialty, gender, race/ethnicity, and number of patients seen per month with OCD were identified by logistic regression as significant contributors toward explaining one's willingness to refer a patient for OCD neurosurgery (Model R2=21%; Table 4). Race/ethnicity was dichotomized as white and nonwhite, and number of patients per month was dichotomized as per Table 2. However, specialty (beta coefficient=1.8121, 95% confidence interval [CI] –12.26 to 15.89) accounted for virtually all of the predictive value.

Only specialty (beta coefficient= –1.2125, 95% CI –18.70 to 16.28) and the degree of contact with neurosurgeons (beta coefficient= –0.5338, 95% CI –8.52 to 7.46) were significantly associated with willingness to refer a patient for PD neurosurgery. Ethnicity, gender, and number of patients seen per month were noncontributory. Model R2 was 12.3%, signifying that only 10% to 15% of the variation in willingness to refer a patient for PD surgery is explained by specialty and contact with neurosurgeons. Parameters explaining the remaining variation are unknown. Variables not included in the logistic regression models for OCD and PD, because of nonsignificance in univariate analyses, included board status, age, number of patients seen with PD per month, and geography.

Selected comments from our physician samples are available on request.

DISCUSSION

Although a common procedure in the 1950s and 1960s for PD, pallidotomy was subsequently performed only rarely because of inconsistent results, especially for the treatment of tremor. With the advent of levodopa therapy, pallidotomy was essentially abandoned. The landmark paper of Laitinen et al. in 199221 thrust pallidotomy back into the mainstream of treatment for otherwise intractable PD; there is a burgeoning medical literature, and numerous centers in North America currently perform the procedure on selected patients.19 Although 60% to 100% of patients in different series have shown some improvement, the mean length of follow-up in these studies has been relatively short. The long-term effects of this operation are unknown.22

For OCD, anterior capsulotomy has been used in Europe for more than three decades, and it has been recently introduced by neurosurgeons in the United States.17 Currently, however, only two centers are actively engaged in OCD neurosurgery: anterior capsulotomies are performed at the Rhode Island Hospital in Providence, and anterior cingulotomies are performed chiefly at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. A double-blind placebo-controlled Gamma Knife (Elekta Radiosurgery, Inc., Atlanta, GA) capsulotomy study is under way at the above centers in collaboration with researchers from Sweden.17 In terms of efficacy, a review of all cases of capsulotomy for OCD previously reported in the literature revealed that 64% were deemed to have a satisfactory result.23 To our knowledge, there are no similar double-blind studies for PD neurosurgery, although the overall extant literature for PD neurosurgery is much greater than for OCD neurosurgery.

Proper utilization of any treatment modality is undoubtedly influenced by the attitudes and knowledge of professionals and patients about that treatment, especially when a diagnosis implies stigmatization. Thus, it is important to assess these attitudes and the factors that contribute to them.24 To our knowledge, this study is the first to attempt to demonstrate how physicians' different conceptualizations of PD and OCD have an impact on awareness of and attitudes toward two similar neurosurgical procedures for these illnesses. Notably, we found that although most psychiatrists surveyed believed that their knowledge of surgical options for the treatment of refractory OCD was inadequate, 83% were aware of such procedures and 74% would refer appropriate patients for neurosurgery. In contrast, very few neurologists were aware of and would refer patients for OCD neurosurgery, with only 17% believing that the operation was efficacious. Almost all neurologists were aware of pallidotomy for PD (99%), and almost that many said they would refer an appropriate candidate. Although they typically saw far fewer patients with PD than OCD, psychiatrists were slightly more aware of neurosurgical procedures for PD than for OCD, although the difference was not significant. These results, as well as data from the comments section of the questionnaires, point to three major themes: 1) poor physician awareness of OCD neurosurgical options relative to PD; 2) risk–benefit bias against OCD surgery by neurologists; and 3) relative lack of “cross-talk” between the specialties of psychiatry and neurology.

Lack of Physician Awareness of Neurosurgery for OCD versus PD

Regarding physician awareness, it has been shown in a study of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) that the more knowledge and clinical experience a professional has, the more positive his or her attitude will be toward ECT as an effective treatment modality.24 Extrapolating that study to our findings with stereotactic neurosurgery, it is disturbing that 17% of psychiatrists and 73% of neurologists were not aware of OCD neurosurgical procedures. There are several likely reasons for the marked disparity in physician awareness between PD and OCD neurosurgical procedures: better publicity in the scientific and academic communities, including sessions at AAN meetings on pallidotomy; greater number of scientific publications on pallidotomy by neurologists and neurosurgeons in leading peer-reviewed journals; and more publicity of pallidotomy for PD in the lay press.

These explanations, of course, beg the question of why there is more physician interest in performing PD neurosurgery than OCD neurosurgery in the first place. One possible factor for the lower preference for OCD surgery, not explored in this paper, is that it may be unduly associated with past “psychosurgical” techniques used for emotional problems, such as lobotomy. There may be a general reluctance for psychiatrists to enter the area of “psychosurgery” (a highly charged and stigmatized term); the reluctance may be due in part to this past association, coupled with the fact that there are laws in some states, such as California, regulating “psychosurgery” without comparable restrictions for neurosurgery.

Another possible explanation for the disparity in awareness between PD and OCD neurosurgery is the different practice patterns of psychiatrists and neurologists, the latter specialty reporting a much greater degree of professional contact with neurosurgeons. In fact, we found that the only factor positively correlated in multivariate linear regression with likelihood of referring for PD surgery, besides specialty, was degree of contact with neurosurgeons. Psychiatrists' significantly less frequent contact with neurosurgeons would perhaps make them less aware of potential surgical approaches for their patients. However, psychiatrists were significantly more likely than neurologists to be aware of OCD neurosurgery.

One might also suspect that familiarity with the disease would lead to increased awareness of treatment options and thus that neurologists (who seldom see OCD patients) would not know about OCD neurosurgery, and psychiatrists (who seldom see PD patients) would not be aware of PD neurosurgery. However, univariate analysis revealed that the number of patients seen with the diagnosis had no impact on degree of awareness of neurosurgical options, and psychiatrists were actually more aware of PD neurosurgery than of OCD neurosurgery.

Neurologist Bias Against OCD Surgery

A second generalization from this study is that despite data to the contrary, very few neurologists acknowledged the potential efficacy of neurosurgery for OCD, although there were no differences between psychiatrists and neurologists in assessing degree of risk. Conversely, greater than 90% of neurologists stated that pallidotomy for PD was efficacious. The published data for pallidotomy have shown a moderate to large amount of improvement in many subjects, but there are no double-blind controlled trials of pallidotomy at present, so at best one can state that the procedure helps certain specially selected patients who meet specific criteria. Likewise, the data for anterior capsulotomy for OCD are limited, although there are numerous uncontrolled data showing efficacy in the 60% to 70% range.23 Given the low percentage of neurologists who were aware of neurosurgical intervention in OCD, we can ask why the vast majority would assume that these procedures are not effective. We speculate that this attitude reflects a fundamental bias of practitioners that psychiatric illnesses are conditions of the mind, whereas neurologic illnesses are brain-based and therefore worthy of aggressive, and possibly heroic, intervention in the form of neurosurgery.

Lack of Communication Between Specialties

A third generalization that can be derived from this study is the relative lack of “cross-talk” between the specialties of psychiatry and neurology. Numerous surveyed physicians responded, “I am a psychiatrist—I know nothing about Parkinson's”; or, “I am a neurologist who never sees any patients with OCD.” We received these typical responses despite evidence of great comorbidities of these two illnesses—PD with depression25 and OCD with tic and neurologic disorders with compulsive features.26 Indeed, both illnesses might best be conceived of as neuropsychiatric illnesses, diseases that the general psychiatrist and general neurologist should be comfortable evaluating. A neuropsychiatric conceptualization4 vaults the limiting and misleading demarcations of traditional concepts of illness and recognizes that both illnesses involve dysfunction in subcortical regions. The fact that only one out of four neurologists was even aware of neurosurgical options for OCD suggests the limited knowledge base that our sample of neurologists had about OCD. Similarly, most psychiatrists rated their knowledge base for PD surgery as inadequate, in stark contrast to neurologists, suggesting that many general psychiatrists might benefit from continuing education training in neurology to keep them abreast of therapeutic options. The relevance for the general psychiatrist is more than simply academic: recent data suggest that PD-induced changes in emotional status, such as depression or hypochondriacal complaints, are favorably influenced by pallidotomy.27 Well-run managed care organizations and multispecialty clinics, which include all academic medical centers, are in an especially good position to foster such “cross-talk” as institutional policy and practice.

Limitations of This Study and Directions for Future Research

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, although our physician samples were largely representative of the national APA and AAN memberships, our results are not necessarily generalizable to non-APA member psychiatrists and non-AAN member neurologists. A recent survey of neurologists suggested that 89.2% of U.S. neurologists are AAN members (C. Keran, personal communication), and we suspect, though we could not confirm, that a similar proportion of U.S. psychiatrists are APA members.

A second potential limitation of our study is that although response rates were quite acceptable for surveys of this type, we cannot exclude the possibility that nonrespondents may have differed from respondents. Third, we relied on self-reports of behavior, which may increase the possibility of response biases. Because there was no independent verification of the data, it is possible that physicians might have overreported their degree of awareness of neurosurgical procedures for fear of appearing ignorant or uninformed. Finally, the questionnaire's brevity encouraged a relatively high response rate but limited our ability to study certain attitudinal dimensions, as well as knowledge, in greater depth. A more robust instrument might have shown additional attitudinal barriers or differences in knowledge between the sampled groups.

Because of these limitations, and the importance these questions have for the practice patterns of neurologists and psychiatrists who treat patients with debilitating OCD and PD, future studies should explore further differences in attitude and knowledge of physicians, including the neurosurgeons who treat these groups of patients. The designers of additional studies might wish to include primary care practitioners' and patients' views toward these two neuropsychiatric illnesses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the administrative assistance of Sylvia Barker and Greg Barker, as well as helpful comments on the manuscript by Ron Rieder, M.D.

|

|

|

|

1 Keller MB, Harrison W, Fawcett JA, et al: Treatment of chronic depression with sertraline and imipramine: preliminary blinded response rates and high rates of undertreatment in the community. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:205–212Medline, Google Scholar

2 Kocsis JH, Frances AJ, Voss C, et al: Imipramine treatment for chronic depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:253–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Hirschfeld RMA, Keller MB, Panico S, et al: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association Consensus Statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277:333–340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Yudofsky SC, Hales RE: The reemergence of neuropsychiatry: definition and direction. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1989; 1:1–6Link, Google Scholar

5 Roth M, Kroll J: The Reality of Mental Illness. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1986Google Scholar

6 Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: The epidemiology and clinical features of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin N Am 1992; 15:743–758Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Jankovic J, McDermott M, Carter J, et al: Variable expression of Parkinson's disease: a base-line analysis of the DATATOP cohort. Neurology 1990; 40:1529–1534Google Scholar

8 Rauch SL, Jenike MA: Neurobiological models of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychosomatics 1993; 34:20–32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Insel TR: Toward a neuroanatomy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:739–744Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Modell JG, Mountz JM, Curtis GC, et al: Neurophysiologic dysfunction in basal ganglia/limbic striatal and thalamocortical circuits as a pathogenetic mechanism of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1989; 1:27–36Link, Google Scholar

11 Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB: The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci 1989; 12:366–375Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Delong MR: Primate models of movement disorders of basal ganglia origin. Trends Neurosci 1990; 13:281–289Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Jankovic J, Lai E, Lea BA, et al: Levodopa-induced dyskinesias treated by pallidotomy. Ann Neurol (in press)Google Scholar

14 Dogali M, Fazzini E, Kolodny E, et al: Stereotactic ventral pallidotomy for Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1995; 45:753–761Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Baron MS, Vitek JL, Bakay RAE, et al: Treatment of advanced Parkinson's disease by GPi pallidotomy:1-year results of a pilot study. Ann Neurol 1996; 40:355–366Google Scholar

16 Jenike MA, Baer L, Ballantine HT, et al: Cingulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a long-term follow-up of 33 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:548–555Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Mindus P, Rasmussen SA, Lindquist C: Neurosurgical treatment for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: implications for understanding frontal lobe function. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:467–477Link, Google Scholar

18 Jenike MA, Rauch SL: Managing the patient with treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: current strategies. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(3, suppl):11–17Google Scholar

19 Favre J, Taha JM, Nguyen TT, et al: Pallidotomy: a survey of current practice in North America. Neurosurgery 1996; 39:883–892Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Beknat J, Ringel S, Vickrey B, et al: Attitudes of U.S. neurologists about the ethical dimensions of managed care. Neurology 1997; 49:4–13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Laitinen LV, Bergenheim AT, Hariz MI: Leksell's posteroventral pallidotomy in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosurg 1992; 76:53–61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Pallidotomy for Parkinson's disease. Med Lett Drugs Ther 1996; 38:107Medline, Google Scholar

23 Cosgrove GR, Rauch SL: Psychosurgery. Neurosurg Clin N Am 1995; 6:167–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Janicak PG, Mask J, Trimakas K, et al: ECT: an assessment of mental health professionals' knowledge and attitudes. J Clin Psychiatry 1985; 46:262–266Medline, Google Scholar

25 Cummings JL: Depression and Parkinson's disease: a review. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:443–454Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Hollander E: Obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders: an overview. Psychiatr Ann 1993; 23:355–358Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Narabayashi H, Miyashita N, Hattori Y, et al: Posteroventral pallidotomy: its effect on motor symptoms and scores of MMPI test in patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders 1997; 3:7–20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar