Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and Related Disorders in Parkinson's Disease

Abstract

This study evaluated the frequency of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS), and related disorders (e.g., tic disorders, trichotillomania, and body dysmorphic disorder) in 100 patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) and 100 individually matched controls. When compared with controls, OCD, OCS, and related disorders were not higher in PD. Findings revealed an association of some OCS with left side motor symptom predominance in PD patients, particularly for symmetry and ordering/arranging. These findings suggest that the right hemisphere likely functions in the expression of OCS.

A chronic psychiatric disorder of unknown etiology, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), is frequently described in patients with primarily basal ganglia ailments, such as Tourette's syndrome, Sydenham's chorea, and Huntington's disease.1 The encephalitis lethargica that was described by von Economo in 1917 frequently presents parkinsonian and obsessive-compulsive symptoms as part of its clinical manifestations.2 Lethargica's histopathological findings also describe lesions in the basal ganglia. These findings suggest that OCD may be more frequent in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD), a frequent disorder characterized mainly by degeneration of neurons in the substantia nigra.

Three previous studies3,4,5 have sought to identify obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) in PD. Tomer et al.3 described higher scores of OCS in PD; Alegret et al.4 found that patients with severe PD presented more obsessive traits than controls, and severity of OCS was related to the severity and duration of PD; and Muller et al.5 found no differences between PD and controls. Tomer et al.3 also observed an association between the severity of motor symptoms on the left side of the brain and OCS related to cleanliness and repetition, whereas they found OCS related to order/routine to be correlated with the right side. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the frequency of OCS, OCD, and related disorders (e.g., tic disorders, trichotillomania, and body dysmorphic disorder) in PD and examine the relationship between OCS and the lateralized expression of motor symptoms.

METHOD

The PD group included 100 outpatients (64 men and 36 women) who were consecutively recruited from the ambulatory of movement disorders of the neurological clinic of the Hospital das Clínicas of University of São Paulo Medical School. From the hospital's internal medicine clinic, 100 outpatients composed a control group. The groups were matched by age and gender. Excluded from the study were PD patients with psychosis or dementia, PD patients who had been submitted to surgical treatment, and control subjects with any disorder of the central nervous system (CNS). Written, informed consent was obtained from each subject after a complete description of the study was given.

Using specific modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, subjects were evaluated for the diagnosis of definite OCD, subthreshold OCD, or OCS only, and related disorders (e.g., tic disorders, trichotillomania, and body dysmorphic disorder). Subthreshold OCD was considered when subjects met all criteria for OCD except for one of the following: (1) recognition that symptoms were excessive and irrational; or (2) recognition that symptoms did not cause distress, last longer than 1 hour, or cause significant interference. When patients met criteria for no more than the presence of obsessions or compulsions, they were considered to have OCS only.6 However, in the main statistical analysis, we regarded patients who met criteria for OCS, subthreshold OCD, and OCD as OCS. The Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) was administrated in order to identify and measure the severity of OCS. In addition, PD subjects were submitted to a neurologic evaluation, blind to the psychiatric interview. The severity of PD was assessed using the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), the Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scale (SEADLS), and the Modified Hoehn Yahr Staging (MHYS).

Statistical analyses were conducted using two-tailed t-student tests when the dependent variable was continuous. When variables were categorical, analyses were performed with the contingency table analysis by chi-square or Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

The mean age for PD patients was 62.2 (SD:11.9) years. The mean age for control subjects was 62.2 (SD:12.0) years. In the PD group, the mean UPDRS was 40.28 (SD:20.6); the mean MHYS was 2.46 (SD:0.89); and the mean SEADLS was 0.73 (SD:0.22). OCS was observed in 17 PD patients (5 OCD, 9 subthreshold OCD, and 3 OCS only) and 12 controls (3 OCD and 9 subthreshold OCD). In both groups, no statistical differences were found in the frequency of OCS (χ2=1.01, df=1, p=0.31) and OCD (Fisher's exact p=0.72). The severity of OCS (Y-BOCS) was similar in both groups (PD group=17.1 SD:5.6; controls=14.1 SD:4.8; F=2.34, df=1, p=0.13).

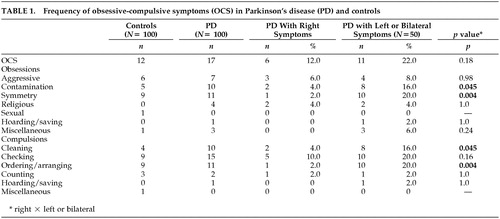

Forty PD patients presented left motor symptoms predominance when assessed for asymmetries. In 50 of these patients, the right side was more affected; and in 10 patients, both sides were equally affected. When compared with those who expressed right motor symptoms predominance (Table 1), patients with left side predominance or bilateral motor symptoms presented a higher frequency of specific OCS, particularly for symmetry obsessions and ordering/arranging compulsions (χ2=8.27, df=1, p=0.004), contamination obsessions, and cleaning compulsions (χ2=4.0, df=1, p=0.04). Among patients with OCS, a higher frequency with left or bilateral motor symptoms began experiencing symptoms before 18 years of age (9 of 11 patients —2 patients could not inform the age of onset), as compared with patients who presented right-side predominance (0 of 4) (Fisher's exact p=0.01).

In PD patients, the presence of OCS did not correlate with rigidity (Fisher's exact p=0.1), tremor (Fisher's exact p=1.0), duration (F=1.86, df=1, p=0.17), severity of PD (UPDRS: F=0.11, df=1, p= 0.74; MHYS: F=0.43, df=1, p= 0.52; SEADLS: F=0.26, df=1, p=0.60), or age of onset of PD (F=0.36, df=1, p=0.55). Additionally, OCS in PD patients was not linked to levodopa therapy (Fisher's exact p=0.68) or the motor (dyskinesias and on/off fluctuations: χ2=0.03, df=1, p=0.86) and psychiatric complications (hallucination: Fisher's exact p=1.0) that accompany levodopa therapy.

Chronic motor tics were diagnosed in 10 PD patients and 6 control subjects (χ2=1.09, df=1, p=0.29). None of the patients or control subjects met criteria for Tourette's syndrome, body dysmorphic disorder, or trichotillomania.

DISCUSSION

We anticipated OCS, OCD, and related disorders (e.g., tic disorders, trichotillomania, and body dysmorphic disorder) to be more frequent in PD patients. Our findings differ from the high frequency of OCS that is reported in the encephalitis lethargica. In fact, different from PD, neuropathological lesions in postencephalitic parkinsonism encompass more widespread sites, including other structures of the mesencephalon besides substantia nigra and the basal ganglia. The frequent association with tics as well as the benefit of neuroleptic augmentation to serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of resistant cases suggest dopaminergic involvement in OCD. Therefore, considering the absence of a relationship between OCS and PD, one could speculate that dopaminergic pathways other than the nigro-striatal (characteristic of PD), such as the mesolimbic pathways, may function in the pathophysiology of OCD.

As anticipated, we found an association of some OCS with left side motor symptom predominance in PD patients, particularly for symmetry and ordering/arranging and, less strikingly, for contamination/cleaning behaviors. These findings suggest a possible role of the right hemisphere in the expression of OCS. Several structural7 and functional neuroimaging8 studies suggest that the right hemisphere serves an important function, specifically the right striatum in the pathophysiology of OCD. Furthermore, neurosurgery9 and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation10 on the right side may be more effective in controlling OCS. In contrast, other studies suggest the participation of the left hemisphere.11 These conflicting results may reflect heterogeneity in the pathophysiology of OCS, raising the possibility that OCS vary according to the dysfunction in each hemisphere.

We also observed an association between early age of onset of OCS (age of onset before 18 years old) and left or bilateral motor symptom expression. In fact, some studies propose that the age of onset of OCS is critical in the classification of OCD subgroups. Early onset cases have been linked to a higher genetic load, male preponderance, and varied symptomatic expression, such as predominance of ordering and arranging behaviors.12 Based on these results, one could speculate that the right hemisphere may be predominant in early-onset OCD.

Standard instruments were not used to measure other prevalent psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and personality disorders, which would have provided a deeper understanding of the relationship among OCS and other significant psychiatric manifestations in PD.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that OCS, OCD, and related disorders are not more frequent in PD patients and the right cerebral hemisphere may be important in the expression of some OCS, particularly those characterized by symmetry obsessions and ordering/arranging compulsions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Wilson Jacob for his help in the patient recruitment process; Geraldo Busatto, and Ben Greenberg for their helpful comments on the revised version of the manuscript; and Raquel do Valle, who participated in the statistical analysis.

This study was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil, to Dr. Maia (97/03804-9) and Dr. Miguel (97/5815-8; 99/08560-6; 99/12205-7) and from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Brazil (521369/96-7) to Dr. Miguel.

|

1 Miguel EC, Rauch SL, Jenike MA: Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1997; 20(4):863–883Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Cheyette SR, Cummings JL: Encephalitis lethargica: lessons for contemporary neuropsychiatry. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 7(2):125–134Link, Google Scholar

3 Tomer R, Levin B, Weiner W: Obsessive-compulsive symptoms and motor asymmetries in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1993; 6:26–30Google Scholar

4 Alegret M, Junqué C, Valldeoriola F, et al: Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001, 70(3):394–396Google Scholar

5 Muller N, Putz A, Kathmann N, et al: Characteristics of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in Tourette's syndrome, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and Parkinson's disease. Psychiatry Re 1997; 70:105–114Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Pauls DL, Alsobrook JP, Goodman W, et al: A family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:76–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Scarone S, Colombo S, Livian S, et al: Increased right caudate nucleus size in obsessive-compulsive disorder: detection with magnetic resonance imaging. Psychiatry Res 1992; 45(2):115–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Rauch SL, Jenike MA, Alpert NM, et al: Regional cerebral blood flow measured during symptom provocation in obsessive-compulsive disorder using oxygen 15-labeled carbon dioxide and positron emission tomography. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51(1): 62–70Google Scholar

9 Lipptz BE, Mindus P, Meyerson BA, et al: Lesion topography and outcome after thermocapsulotomy or gamma knife capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: relevance of the right hemisphere. Neurosurgery 1999; 44(3):452–458Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Greenberg BD, George MS, Martin JD, et al: Effect of prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a preliminary study. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154(6): 867–869Google Scholar

11 Benkelfat C, Nordhal TE, Semple WE, et al: Local cerebral glucose metabolic rates in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients treated with clomipramine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47(9): 840–848Google Scholar

12 Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, et al: Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the Pediatric Literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37(4):420–427Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar