Effectiveness of Switching to Quetiapine for Neuroleptic-Induced Amenorrhea

Abstract

This study investigated the effectiveness and tolerability of a switching strategy using quetiapine in 16 women with schizophrenia who were suffering from haloperidol- or risperidone-induced amenorrhea. Findings revealed that 10 patients (71.6%) resumed menstruation, without worsening of psychotic symptoms.

Conventional antipsychotics, including haloperidol, have been reported to elevate serum prolactin levels through the blockade of dopamine 2 (D2) receptors in the brain.1 Some reports have indicated that risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic, is responsible for a prolactin increasing effect.2 Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia has been associated with oligospermia, impotence, and reduced sexual desire in male patients and gynecomastia, menstrual dysfunction, and galactorrhea in females.3 Decreases in prolactin levels are most likely the result of methods such as dose reduction or discontinuation of prior antipsychotic therapy. However, these methods are not available to some patients who used them in prior trials resulting in worsening of psychotic symptoms.

Quetiapine, a novel and atypical antipsychotic agent that possesses a similar binding profile to the original atypical antipsychotic, clozapine, is believed to have minimal effect on serum prolactin levels.4,5 However, few reports compare the prolactin levels in the same patients before and after switching from other antipsychotics to quetiapine.6 Data on the efficacy and safety of a switching strategy, using quetiapine in patients suffering from adverse events due to neuroleptic-induced hyperprolactinemia, have not been found.

In this study, we observed female schizophrenic patients who were treated with haloperidol or risperidone, suffered amenorrhea, and experienced unwanted outcomes due to dose reduction of previous antipsychotics. In this population, the safety and potential usefulness of a switching strategy using quetiapine were assessed.

METHODS

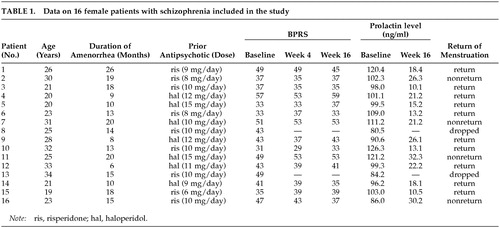

The subjects, 16 female patients with schizophrenia, suffered from haloperidol- or risperidone-induced amenorrhea and could not reduce the dose of haloperidol or risperidone because of worsening of psychotic symptoms. At study entry, they hadn't been treated with any D2 blockers other than haloperidol or risperidone. To participate in the study, they fulfilled the DSM-4 criteria for schizophrenia and gave written, informed consent.

The total period of this study was 16 weeks. The overlapping method of tapering and titration was selected for the switching protocol, and we started at the same time in order to decrease the dose of haloperidol or risperidone and initiate quetiapine 50 mg/day. Then, according to the clinical response, haloperidol or risperidone was gradually withdrawn; and quetiapine was slowly titrated up from the starting dose of 50 mg/day to a dose of 300 mg/day within 4 weeks. During the next 12 weeks, fixed-dose (300 mg/day) quetiapine therapy was continued.

Each day, quetiapine was administered in two divided doses. Generally, with the exception of risperidone or haloperidol, the preexisting medication remained unchanged. Additional psychotropic medications, however, were permitted for: (1) acute agitation (diazepam up to 10 mg/day); (2) insomnia (brotizolam up to 0.5 mg/day or acceptable alternatives at recommended doses e.g., flunitrazepam, triazolam, or brotizolam) (3) and emergent extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) or akathisia of at least moderate severity (anticholinergic medication at recommended doses). Nonpsychotropic medications were permitted for minor physical complaints, including nausea or headache. Plasma prolactin levels were measured at baseline before the study began and again at the end. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and adverse events were recorded at baseline, week 4, and the end.

Plasma prolactin levels were analyzed using the paired t test, and BPRS scores were assessed using repeated measures of analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences in prolactin levels between patients who resumed menstruation and those who did not were analyzed with the unpaired t test. Results were considered significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

A summary of the data is presented in Table 1. Fourteen out of 16 patients completed the study. One patient withdrew during week 2 after developing untreatable akathisia, and another patient withdrew before week 4 due to headache and nausea. Some patients developed somnolence, dizziness, and dry mouth, which were tolerable and not clinically significant.

All paticipants showed decreases in plasma prolactin levels after switching to quetiapine. By the end of the study, mean (±SD) plasma prolactin levels were reduced from 104.6±11.7 ng/ml at base line to 19.9±7.1 ng/ml (p=0.0001). The mean (±SD) total score of BPRS was not altered significantly at 3 assessment points (baseline, 41.9±7.9; week 4, 41.0±8.0; week 16, 41.4±8.2) (p=0.70). Of the 14 subjects who completed the study, 10 resumed normal menstruation (71.6%). For both the group with restoration of menses and the group with persistent amenorrhea, the mean plasma prolactin levels were 104.7±11.8 ng/ml and 105.2±14.9 ng/ml at baseline and 16.8±5.3 ng/ml and 27.5±4.9 ng/ml at endpoint, respectively. The endpoint plasma prolactin levels were elevated more significantly in the persistent amenorrheic group than in the group with restoration of menses (p=0.046).

DISCUSSON

In all 14 patients who completed the study without worsening of psychotic symptoms, plasma prolactin levels showed a marked reduction after switching from haloperidol or risperidone to quetiapine. Among the 14, 10 (71.4%) resumed normal menstruation. These results suggest that switching to quetiapine may be an appropriate treatment strategy for patients suffering from neuroleptic-induced amenorrhea that is brought on by conventional antipsychotics or risperidone. A recent study on positron emission tomography revealed that quetiapine shows a transient and high D2 occupancy 2 to 3 hours after one final dose, with a rapid decline during the next 9 hours.7 Conversely, haloperidol demonstrates prolonged D2 occupancy in the same mode.8 We hypothesize that transient and high D2 occupancy may be sufficient to induce antipsychotic response and rapid release of quetiapine from D2 receptors does not lead to drug accumulation, preventing sustained prolactin elevation.9

In this study, quetiapine was administered at doses within the recommended range, while doses of risperidone and haloperidol were rather high. The use of supratherapeutic doses may not allow for reasonable comparison between quetiapine and other drugs. In the general clinical settings, however, some patients maintain suitable conditions only when antipsychotics beyond the range of recommended doses are prescribed, and such patients are likely to experience adverse occurrences that are associated with antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia. Therefore, in the population used in this study, data on the method of switching from other antipsychotics to quetiapine are beneficial for clinicians, especially when the dose reduction of previous antipsychotics have resulted in unwanted outcomes.

This study lacks a control group and data on the return of menses in patients who remained on haloperidol or risperidone. Both a control group and information on the menstruation of subjects who remained on haloperidol or risperidone are necessary if we are to conclude that switching to quetiapine is significantly greater than the base rate for the spontaneous recovery of menses. Additionally, no data on quetiapine's effect at higher doses is presented, which is necessary for accurate evaluation of this therapy.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported finding of the effectiveness of a switching strategy using quetiapine for women with schizophrenia who suffer from risperidone- or haloperidol-induced amenorrhea. However, we cannot inevitably conclude that this would have been the case had we administered quetiapine as the initial treatment to newly diagnosed female patients in the relevant age range. Granting the small sample size and short duration of the study, results should be viewed as preliminary. Future studies must include a larger sample size and longer duration in order to substantiate possible benefits of the switching strategy.

|

1 Nordstrom AL, Farde L: Plasma prolactin and central D2 receptor occupancy in antipsychotic drug-treated patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 18:305–310Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 David SR, Taylor CC, Kinon BJ, et al: The effects of olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on plasma prolactin levels in patients with schizophrenia. Clin Ther 2000; 22:1085–1096Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Spark RF: Prolactin. In: Lavin N, ed. Manual of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2nd ed. Little, Brown and Co, Boston 1994; pp. 97–103Google Scholar

4 Hamner MB, Arvanitis LA, Miller BG et al: Plasma prolactin in schizophrenia subjects treated with Seroquel (ICI 204,636). Psychopharmacol Bull 1996; 32:107–110Medline, Google Scholar

5 Petty RG: Prolactin and antipsychotic medications: mechanism of action. Schizophr Res 1999; 35 Suppl:S67–73Google Scholar

6 Emsley RA., Raniwalla J, Bailey PJ, et al: A comparison of the effects of quetiapine (‘Seroquel’) and haloperidol in schizophrenic patients with a history of and a demonstrated, partial response to conventional antipsychotic treatment. PRIZE Study Group. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 15:121–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Kapur, S, Zipursky, R, Jones C, et al: A positron emission tomography study of quetiapine in schizophrenia: a preliminary finding of an antipsychotic effect with only transiently high dopamine D2 receptor occupancy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:553–559Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Kapur S, Remington G, Jones C, et al: High levels of dopamine D2 receptor occupancy with low-dose haloperidol treatment: a PET study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:948–950Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Kapur S, Seeman P: Does fast dissociation from the dopamine D(2) receptor explain the action of atypical antipsychotics?: a new hypothesis. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:360–369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar