The Relationship Between Age and Cognitive Function in HIV-Infected Men

Abstract

Several studies have identified increased age as a risk factor for the development of cognitive impairment in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected subjects, but few have examined the potential synergistic effect of age and HIV serostatus on cognitive decline. The authors examined the possible combined effect of age and HIV serostatus on cognitive decline in 254 subjects stratified by age group and HIV status. After controlling for the effect of education, there were significant effects for serostatus and age group on overall cognitive impairment and a number of neuropsychological measures but no interaction effects. These data suggest that older seropositive individuals are not at an increased risk for HIV-related cognitive impairment when normal age-related cognitive changes are considered.

In the early years of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, most patients were young, and the median survival following a diagnosis of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) was relatively brief.1,2 In that context, consideration of the impact of age was not critical. With the advent of new therapeutic agents such as protease inhibitors and the development of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), long-term post-AIDS survival is increasingly common.2 The number of older patients with chronic HIV infection is therefore likely to increase, which necessitates investigation into the impact of increasing age on the disease. One hypothesis that has been explored suggests that advancing age may be an important risk factor for the development of HIV-related cognitive impairment.

While controversial at one time, there is an emerging consensus that neuropsychological performance is compromised in a subgroup of patients at early stages of infection.3 There is also substantial evidence suggesting that cognitive impairment is increasingly common and severe in more advanced stages of immune decline.3 The impact of age on some aspects of neuropsychological performance is well established. In addition, data indicate that age at seroconversion is significantly associated with HIV disease progression and survival time.1 The possibility of an interaction between age and disease level on cognitive function has not been explored thoroughly.

Given that both age and HIV status have been established as independent risk factors for the development of cognitive impairment, it is both reasonable and important to question whether the interaction of these two factors may constitute increased risk of impairment in HIV-infected individuals. While several studies have explored the impact of age on cognitive function in HIV-infected subjects,4–7 few have examined the interaction of age and disease status.8,9 In addition, some studies have not adequately controlled for potential confounding variables. For example, one study found that age was significantly associated with neuropsychological performance, although this association disappeared after methadone consumption and years of drug dependency were added to the regression.7

Another study that examined the interaction of age and HIV disease status on cognitive impairment did not find an interaction effect.8 However, this study employed a limited neuropsychological test battery that may be insufficiently sensitive to subtle impairment.3 The only other study to explore the age-serostatus interaction found a significant effect, showing that AIDS patients over age 50 had higher rates of impairment than younger patients in earlier stages of disease progression.9 In view of this unresolved question, this study examines the interaction between age and cognitive impairment based on an extensive series of neuropsychological tests administered to a large sample of HIV-seropositive patients and HIV-seronegative comparison subjects.

METHOD

Subjects

The sample included 66 seronegative comparison subjects and 188 HIV-seropositive subjects grouped according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) criteria: 108 stage A, 32 stage B, and 48 stage C. Subjects were gay or bisexual, predominantly Caucasian (92.1%), male volunteers who were recruited specifically for participation in this research project. No attempt was made to select subjects with subjective complaints of cognitive impairment. Individuals with a history of intravenous drug use, head injury resulting in unconsciousness for more than 60 minutes, neurological disorders, or learning disorders were excluded.

Subjects were also stratified by age based on the distribution of the entire sample. Subjects aged 20 to 35 years composed the younger group, while subjects aged 45 to 60 years composed the older group. All subjects whose ages fell outside these selection criteria were excluded from the sample to ensure separation between the age groups. Demographic data are summarized in Table 1, which reveals that the older group had significantly more years of education than the younger group. Education was therefore included as a covariate in the analyses of neuropsychological performance.

Both comparison subjects and HIV-positive subjects were informed of the study through registration with an AIDS Clinical Trials Unit (ACTU), through local HIV-related community support groups, by newspaper advertisements, or by word-of-mouth. Subjects were provided with an informational brochure describing the study. All subjects received detailed descriptions of the nature and purposes of the study, and all gave written, informed consent. Blood samples were drawn during their regularly scheduled ACTU visits, which corresponded to the time of enrollment in the current study. Prior to their enrollment in this study, subjects were followed as part of a cohort in the ACTU. Serostatus was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and positive assays were confirmed by Western blot.

Procedures

Subjects completed an extensive neuropsychological battery that included standardized neuropsychological measures and a series of simple and choice reaction-time measures. Because the nature of cognitive changes in HIV infection has been characterized as a subcortical dementia,10 tests were selected on the basis of demonstrated sensitivity to the effects of subcortical dementia in general and HIV infection in particular. The following standardized neuropsychological measures were used: WAIS-Revised, Selective Reminding Test, Visual Memory Span Forward and Backward from the Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised, Verbal Concept Attainment Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Verbal Fluency, Figural Fluency, Trail Making A and B, Grooved Pegboard, and the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test.11 Simple and choice reaction-time measures were also included because these tasks have consistently been found to be sensitive to the effects of HIV infection.12 In addition to performance on the individual neuropsychological measures, a summary performance score was computed for each subject, representing the number of measures on which the subject’s performance was one SD below the mean of the comparison group. Subjects also completed the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety.

RESULTS

The data were analyzed using a 4×2 Analysis of Variance (Disease Status by Age group). As mentioned above, this analysis revealed a significant effect of age on education (F=5.28, df=1, 234, p=0.022). It was therefore essential to include education as a covariate in our analyses in order to examine the interaction effect of age and disease level on cognitive performance independent of this confounding variable.

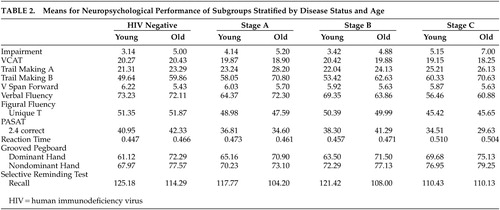

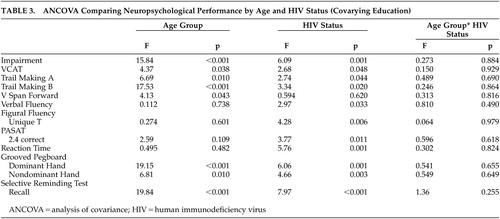

The initial analysis of neuropsychological performance was based on an overall impairment score that was calculated by the total number of measures on which an individual achieved a score that was one SD below the mean of the comparison group. As presented in Table 2 and Table 3, after controlling for education, there were significant effects for age group (F=15.84, df=1, 245, p<0.001) and HIV status (F=6.09, df=3, 245, p=0.001) on the overall measure of impairment, but there was not a significant interaction effect (F=0.273, df=3, 245, p=0.844).

In addition to analyzing overall cognitive impairment, it was of interest to determine whether any specific areas of neuropsychological performance were impacted by the interaction of age and disease status. This was accomplished by a series of ANCOVAs, controlling for the effect of education. As can be seen in Table 3, while results of these analyses revealed several significant main effects for both age group and HIV status, respectively, there were no significant interaction effects on any of the neuropsychological measures. Since the cell size in the older subgroups was considerably smaller than in the younger groups, it was essential to address the potential impact on these analyses. Analyses of homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) demonstrated no significant differences in variances among the age X HIV status subgroups, which suggests that the lack of differences between group means cannot be attributed to cell size. Furthermore, the data were reanalyzed after combining the two symptomatic subgroups to increase sample size. These reanalyses again demonstrated significant effects for HIV status and age but again failed to demonstrate any significant interaction effects.

In addition, it was recognized that the criterion for defining the older age group was different than that used in other studies (45 years of age versus 50 years of age in other studies).8–9 Regardless of the criterion used, however, this is a relatively arbitrary distinction. Therefore, to avoid the problems inherent with such an arbitrary criterion, it was decided to directly examine the relationship between aging and cognitive performance in the HIV-positive and HIV-negative subgroups. Correlation coefficients (controlling for the effects of education) were computed separately, and the significance of the difference between correlations was calculated using Fisher’s Z-transformation. This allowed an analysis of all available data. It was hypothesized that an interaction between HIV stage and age would result in significantly different correlations between age and performance in the comparison and HIV-positive subjects. The results of these analyses failed to demonstrate any significant differences in these correlations.

DISCUSSION

These data fail to provide support for the hypothesis that advancing age is a risk factor for the development of HIV-related cognitive impairment. Age and disease status had independent effects on cognitive function, but there were no significant interactions either on a summary measure of performance or on individual test scores. Both age and disease status were shown to have effects on measures of executive function (VCAT and Trail Making B), memory (Selective Reminding – Delayed Recall), and dexterity (Grooved Pegboard). Disease stage also affected measures of reaction time, information processing speed, and fluency (verbal and nonverbal). The demonstrated effects of HIV are consistent with the characterization of HIV-associated cognitive impairments as a subcortical dementia.10 These results cannot be attributed to education, which was included as a covariate in all analyses. In addition, the groups did not differ regarding depression or estimates of weekly alcohol consumption. Therefore, the observed results cannot be attributed to these potentially confounding variables. Further, these results cannot be attributed to differences in cell size or variability as no significant differences were revealed when partial correlation coefficients between age and neuropsychological performance across disease stage were compared.

Although our results are consistent with previous studies that found both older age4–7 and disease status to significantly impact cognitive impairment in HIV-seropositive subjects, this investigation did not find the hypothesized synergistic effect between aging and HIV serostatus when education was controlled. These findings are consistent with a previous study,8 which concluded that older seropositive individuals are not at an increased risk for HIV-related cognitive impairment when normal age-related cognitive changes are considered. The study included 76 subjects, 29 of which were over age 55 (range=21–69), and found a trend toward a significant age by serostatus interaction on only one measure. In contrast, another study9 found an age by serostatus interaction, in that AIDS patients over age 50 had higher rates of impairment than younger patients at earlier stages of disease progression. The study had a somewhat larger sample of older subjects and stratified subjects according to age (less than 40, 40–49, and greater than 50). The mean age of our older subjects (47 years) is comparable to the mean age of the older subjects in these studies (47.2 and 44.5), although the current study had only 25 subjects older than age 45 in the seropositive group. The latter9 study had a substantially larger subgroup of subjects older than age 50.

In addition to the current findings, data from the two previous investigations8,9 help to identify critical factors that will be needed to resolve the question of an age-serostatus interaction. One study9 that demonstrated an age by serostatus interaction was based on a clinical sample, whereas the current study was based on a research cohort. In contrast, the study that utilized a less extensive test battery8 and/or relatively smaller numbers of older subjects did not find evidence of this interaction. Previous studies have stratified subjects according to age, although the criteria have been arbitrary and inconsistent across studies. When the impact of age was examined as a continuous variable in the current study, there was no difference in the relationship of age to cognitive function. Furthermore, the disease stratifications have been based on disease classification criteria rather than on virologically based criteria such as viral load. As the epidemic continues to evolve and advances in treatment continue, there will be an increased number of older individuals living with HIV and AIDS.2 The generalizability of the current results is limited since the cohort was composed of primarily white homosexual/bisexual males. Other samples with greater gender and ethnic diversity should also be studied since differences in access to health care as well as differences in diagnostic recognition could influence the interaction of age and HIV serostatus. Future studies with larger cohorts of older subjects that employ comprehensive evaluations will be necessary in order to clearly identify this question. If such an interaction exists, it will be essential to determine whether there is an age or serostatus threshold at which this occurs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the NIMH (MH45649), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA10248), and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA11720).

|

|

|

1 Babiker AG, Peto T, Porter K, et al: Age as a determinant of survival in HIV infection. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54:S16-S21Google Scholar

2 Justice AC, Landefeld CS, Asch SM, et al: Justification for a new cohort study of people aging with and without HIV infection. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54:S3-S8Google Scholar

3 White DA, Heaton RK, Monsch AU: Neuropsychological studies of asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-type-1 infected individuals. JINS 1995; 1:304–315Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Janssen RS, Nwanyanwu OC, Selik RM, et al: Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus encephalopathy in the United States. Neurol 1992; 42:1472–1476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 McArthur JC, Hoover DR, Bacellar H, et al: Dementia in AIDS patients: incidence and risk factors. Neurol 1993; 43:2245–2252Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Kim DH, Jewison DL, Milner GR, et al: Neurocognitive symptoms and impairment in an HIV community clinic. Can J Neurol Sci 2001; 28:228–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Pereda M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Gomez Del Barrio A, et al: Factors associated with neuropsychological performance in HIV-seropositive subjects without AIDS. Psychol Med 2000; 30:205–217Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Van Gorp WG, Miller EN, Marcotte TD, et al: The relationship between age and cognitive impairment in HIV-1 infection: findings from the multicenter AIDS cohort study and a clinical cohort. Neurol 1994; 44:929–935Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Hardy DJ, Hinkin CH, Satz P et al: Age differences and neurocognitive performance in HIV-infected adults. N Z J Psychol 1999; 28:94–101Google Scholar

10 Price RW, Brew B, Sidtis J, et al: The brain in AIDS: central nervous system HIV-1 infection and AIDS dementia complex. Science 1988; 239:586–592Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Lezak MD: Neuropsychological Assessment. New York, Oxford University Press, 1983Google Scholar

12 Bornstein RA, Nasrallah HA, Para MF, et al: Neuropsychological performance in asymptomatic HIV infection. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 4:386–394Link, Google Scholar