Relation Between Estradiol and Negative Symptoms in Men With Schizophrenia

Abstract

The authors tested the hypothesis that estradiol would be associated with negative symptoms in 30 male schizophrenia inpatients. Medications were switched from typical to atypical antipsychotics. Estradiol concentrations were inversely correlated with negative symptoms significantly before the switch and at a trend level of significance after the switch. Changes in negative symptoms were positively correlated with those in estradiol concentrations at a trend level of significance. Estradiol could be a biological marker for negative symptoms even in male schizophrenia patients.

Epidemiological, clinical, and animal studies have suggested that estrogens serve as protective factors in schizophrenic disorders.1,2 For example, gender effects have been consistently reported in schizophrenia, with men having an earlier age of onset.3 Interestingly, some recent studies have reported that psychotic symptoms in women with schizophrenia receiving estradiol as an adjunct to antipsychotic treatment improved more than those receiving antipsychotic drugs alone.4,5 Moreover, better treatment responses during phases when estrogen levels were higher have been reported.6 Well in line with these findings, we observed that responders to switching medications from typical to atypical antipsychotic drugs had higher baseline serum estradiol concentrations than nonresponders even in men.7,8 Therefore, in this study, we tested the hypothesis that estradiol would be associated with psychotic symptoms, particularly negative symptoms in men with schizophrenia.

METHODS

In this prospective, open-label study, 30 male inpatients with chronic schizophrenia, age 35.9 (SD=10.0) years, who were ill for 13.4 (SD=7.8) years, and was receiving a dose of haloperidol-equivalent 16.8 (SD=12.2) mg/day,9 were recruited. The diagnosis was based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of APA (DSM)-IV criteria for schizophrenia,10 a detailed clinical interview, and review of the prior records. In the subjects, hepatic and renal functions were normal, and subjects were excluded if they presented with any organic central nervous system (CNS) disorder, significant substance abuse, or mental retardation. The study was approved by the relevant ethics committee and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Finland, II. The patients who gave informed consent to the research participated in this study.

The patients were included because their conditions were considered not to be optimal due to the lack of treatment responses or adverse events to the typical antipsychotic drugs. These patients were switched from typical to atypical antipsychotic drugs, olanzapine, perospirone, or quetiapine. Basically, olanzapine, perospirone, or quetiapine was added onto the previous antipsychotic drugs (33.3% of pretreatment equivalent during week 2,66.6% during week 4, and 100% during week 6). At the same time, the previous medications, including anticholinergic medications were gradually tapered (pretreatment decreased 33.3% week 2, 66.6% week 4, and 100% week 6).

Psychotic symptoms were assessed, using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS 1-7 score),11 by trained psychiatrists in the morning of the day when blood samples for the hormone estimation were drawn. Based on previous groupings of BPRS symptoms,12 four symptoms, conceptual disorganization, grandiosity, hallucinatory behavior and unusual thought content, and four symptoms, emotional withdrawal, motor retardation, blunted affect, and disorientation, were derived as positive and negative symptoms, respectively.

The neuroendocrine and clinical assessments were done before, and a mean period of 81.1 (12.2) days later, after switching to olanzapine (N=8), perospirone (N=9) or quetiapine (N=13) in a mean dose of 15.6 (5.0), 43.1 (9.8) and 559.6 (166.9) mg daily, respectively. Serum prolactin, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) were assayed by immunoradiometric assays (IRMAs), and testosterone and estradiol were assayed by radioimmunoassays (RIAs). The coefficients for intraassay and interassay variation were ≤7.1% and ≤3.6% for prolactin, ≤5.3% and ≤9.0% for LH, ≤4.6% and ≤2.8% for FSH, ≤11.2% and≤11.4% for testosterone, and ≤7.0% and ≤8.1% for estradiol. Data were collected from all subjects.

The data analysis was conducted using StatView-5.0J for Mac software. The changes of hormonal levels and clinical assessment scores between groups were compared by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. Pearson’s correlation was used to examine the relationships between variables. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

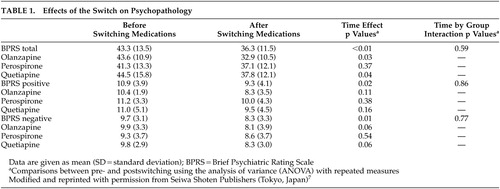

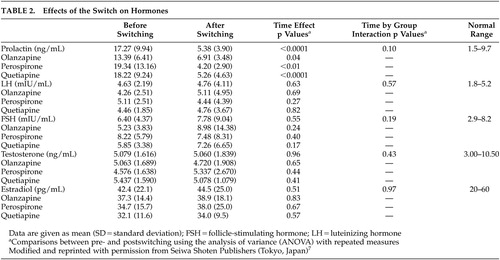

The effects of the switch on psychopathology and hormones are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. As reported elsewhere,7,8ANOVA revealed significant time effects for scores of the BPRS total [F(1, 27) =10.4, df=1, p<0.01], negative [F (1, 27) =6.1, df=1, p=0.01], and positive symptoms [F (1, 27) =5.6, df=1, p=0.02]. Also, a significant time effect was observed for the serum prolactin concentrations [F(1, 27) =45.1, df=1, p<0.0001], but not for the serum LH, FSH, testosterone or estradiol concentrations. However, there were no significant group effects or time-by-group interactions.

Meanwhile, before the switch, the serum estradiol concentrations were inversely correlated with the negative symptom scores (r=-0.38, p=0.03, N=30), but not with the BPRS total or positive symptom scores. Such a correlation was found at a trend level of significance even after the switch (r=-0.34, p=0.06). Moreover, changes in the negative symptoms from baseline were positively correlated with those in the serum estradiol concentrations at a trend level of significance (r=0.33, p=0.07). However, there were no significant correlations between other hormones and psychotic symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have suggested a role of estrogen in psychopathology, particularly negative symptoms, in schizophrenia. For example, gender differences in negative symptoms have been reported quite consistently in schizophrenia.3 Also, an inverse association between estradiol levels and anergia scores has been reported.13 Moreover, the use of estrogen in conjunction with antipsychotic medication in women with schizophrenia has been suggested to reduce negative symptoms.4,5 However, no studies were conducted regarding a role of estrogen in men with schizophrenia. As shown in women, we found an inverse association between estradiol levels and negative symptoms. Moreover, changes in the negative symptom scores from baseline were correlated with changes in the serum estradiol concentrations. The results may be interpreted in two ways: either estradiol affected the psychopathology in schizophrenia or the pathological processes of schizophrenia affected the estradiol levels. Estradiol may have contributed to the improvement in negative symptoms by modulating monoaminergic neurotransmitter systems (e.g., interacting with dopamine, serotonin, and/or GABA receptors), and/or providing neuroprotective effects (e.g., protecting cells from death by increasing the expression of proteins like Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl).1,2 Also, prolactin reduction may have worked in favor of estradiol, since prolactin has been suggested to act at the hypothalamus to suppress gonadal function.14 Moreover, estrogen has been reported to have an antipsychotic effect or mimic the action of antipsychotic drugs.4 Although the design of the study makes it difficult to draw conclusions about causality, our results suggested that estradiol could be a biological marker particularly for negative symptoms even in men with schizophrenia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for the cooperation of Drs. Akira Fujii and Ichiro Kawamura (Anan, Japan) and their staff.

This study was supported in part by a grant from Pharmacopsychiatry Research Foundation.

|

|

1 Rao ML, Kolsch H: Effects of estrogen on brain development and neuroprotection-implications for negative symptoms in schizophrenia (1). Psychoneuroendocrinol 2003; 28 (Suppl 2):83–96Google Scholar

2 Riecher-Rössler A: Oestrogen effects in schizophrenia and their potential therapeutic implications—review. Arch Women Ment Health 2002; 5:111–118Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Moriarty PJ, Lieber D, Bennett A, et al: Gender differences in poor outcome patients with lifelong schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2001; 27:103–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Kulkarni J, Riedel A, de Castella AR, et al: Estrogen—a potential treatment for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2001; 48:137–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Lindamer LA, Buse DC, Lohr JB, et al: Hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women with schizophrenia: positive effect on negative symptoms? Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49:47–51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Gattaz WF, Vogel P, Riecher-Rossler A, et al: Influence of the menstrual cycle phase on the therapeutic response in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:137–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Kaneda Y, Kawamura I, Fujii A, et al: Impact of a switch from typical to atypical antipsychotic drugs on quality of life and gonadal hormones in male patients with schizophrenia drugs (Japanese version). Rinsyo Seisin Yakuri Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol, 2004; 7:483–492.Google Scholar

8 Kaneda Y, Kawamura I, Fujii A, et al: Impact of a switch from typical to atypical antipsychotic drugs on quality of life and gonadal hormones in male patients with schizophrenia drugs (English version). Neuroendocrinol Lett, 2004; 25:135–140.Medline, Google Scholar

9 Inagaki A, Inada T, Fujii Y, et al: Dose equivalence of psychotropic drugs (in Japanese). Tokyo, Seiwa Shoten Co., Ltd., 1999Google Scholar

10 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM-IV). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

11 Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Guy W (ed.): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (publication ADM 76–338). Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976Google Scholar

13 Riecher-Rössler A, Häfner H, Stumbaum M, et al: Can estradiol modulate schizophrenic symptomatology? Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:203–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Franks S, Jacobs HS, Martin N, et al: Hyperprolactinaemia and impotence. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1978; 8:277–287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar