The Use of Olanzapine in the Treatment of Negative Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

The authors report findings from an 8-week, open-label trial conducted to evaluate efficacy of olanzapine in treating negative symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Subjects were AD patients age 50 and older who exhibited untreated neuropsychiatric symptoms. Findings suggest that a therapeutic profile for olanzapine may be appropriate for AD patients experiencing neuropsychiatric problems.

The deleterious effect neuropsychiatric symptoms have on the course of illness, level of care, and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been well documented.1 Previous studies,2,3,4 however, have tended to focus on positive (e.g., agitation, delusions, hallucinations) rather than negative symptoms (e.g., avolition, apathy), even though negative symptoms are reportedly more prevalent and contribute significantly and independently to the rate of decline in dementia.5 Preliminary results from recent clinical trials treating a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with AD suggest that an atypical antipsychotic may provide broader efficacy with less adverse reactions than conventional neuroleptics.6 To date, however, there have been few studies that have examined the efficacy of pharmacological agents including atypical antipsychotics in treating negative symptoms in AD.7

We report the findings from an 8-week, open-label trial conducted to evaluate the efficacy of olanzapine in treating negative symptoms. Subjects were recruited from a convenience sample at a university-based dementia program. Eligibility was limited to patients age 50 or older who were diagnosed with AD, according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA) criteria, and who exhibited untreated neuropsychiatric symptoms, as evidenced by the Behavioral Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Scale (BEHAVE-AD).8 Using a protocol approved by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board, decisional capacity was determined. Consent or assent was obtained from subjects, and consent was obtained from family caregivers. Fourteen patients (8 women) and family caregivers enrolled in the study, with one subject dropping out after week 1, following hospitalization for a preexisting cardiac problem.

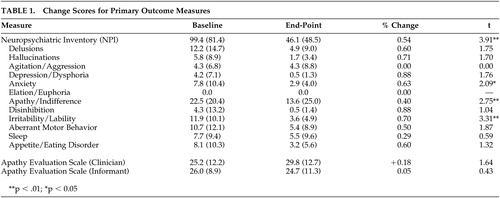

Olanzapine was started at 2.5 mg-per-day, increasing in weekly 2.5-mg increments. If tolerated, the dose was maintained at 7.5-mg-per-day for 3 weeks prior to increasing to the next dose. Any dose was decreased by 2.5-mg-per-day if the subject or caregiver indicated an adverse reaction. The average olanzapine dose during the treatment phase was 6.2 ± 1.9 mg-per-day, with a range from 2.5 to 10.0 mg. Primary outcome measures included the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)9 and the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES),10 which were administered during weeks 1, 5, and 9. Safety measures were collected weekly and included the AMDP-5,11 Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS),12 and Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale.13 Baseline to endpoint data were analyzed using Student’s t tests.

A total of 13 dyads (93%) completed the study. Mean length of AD was 3.7 years ± 1.7, with a consensus staging of early to moderate severity (CDR =1.4 ± 0.5). Overall results revealed a 54% reduction (p<0.01) in neuropsychiatric symptoms, with 10 of the 12 dimensions rated as improved at endpoint (Table 1). Caregivers reported a significant decline in subject levels of apathy/indifference (p<0.01). Despite overlap between NPI apathy and AES scale items, AES ratings did not result in significant change. One factor that may account for this discrepancy is that NPI scales consider frequency and severity of symptoms in calculating a score, while the AES only assesses frequency. Analysis of baseline to endpoint results revealed no significant change in subject blood pressure, weight, extrapyramidal symptoms, or associated movement problems.

In interpreting these findings, it is important to note that these data were collected from an open-label clinical trial without benefit of a placebo comparison group. Nevertheless, results from this study support previous research findings indicating that atypical antipsychotic agents are effective in treating positive neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with AD and provide nascent support for its use in treating negative symptoms. Moreover, olanzapine was well tolerated by all study participants. Therefore, these results suggest that the therapeutic profile for olanzapine may be particularly well suited for patients with AD experiencing a broad array of neuropsychiatric problems.

|

1 Reichman W, Coyne A: Amirneni, S. et al: negative symptoms in alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:424–426Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Lyketsos CG, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE): Alzheimer disease trial methogology. Am J Ger Psychiatry 2001; 9(4):346–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Irizarry MC, Ghaemi SN, Lee-Cherry ER, et al: Risperidone treatment of behavioral disturbances in outpatients with dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999; 11(3):336–342Link, Google Scholar

4 Katz IR, Jeste DV, Mintzer JE, et al: Comparison of risperidone and placebo for psychosis and behavioral disturbances associated with dementia: a randomized, double-blind trial. Risperidone Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(2):107–115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Doody R, Massman P, Mahurin, R. et al: Positive and negative neuropsychiatric features in alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry 1995; 7:54–60Link, Google Scholar

6 Negro A, and Reichman, W: Risperidone in the treatment of patients with alzheimer’s disease with negative symptoms. Int Psychogeriatrics 2000; 12:527–536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Morris JC, Cyrus PA, Orazem, J et al: Metrifonate benefits cognitive, behavioral, and global function in patients with alzheimer’s disease. Neurol 1998; 50:1222–1230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Reisburg B, Borenstein J, Salob, S. et al: Behavioral symptoms in alzheimer’s disease: phenomenology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 48(suppl 5):9–15,1987Google Scholar

9 Cummings J, Mega M: Gray, K. et al: The neuropsychiatric inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurol 1994; 44:2308–2314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Marin, R: Apathy-Who cares? An introduction to apathy and related disorders of diminished motivation. Psychiatr Annals 1997; 27:18–23Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Bobon D, and Woggon, B: The amdp-system in clinical psychopharmacology. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 148:467–468Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Lane R, Glazer W, Hansen T: Assessment of tardive dyskinesia using the abnormal involuntary movement scale. J Nervous Ment Disorders 1985; 173:353–357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Barnes, T: A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:672–676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar