Family History of Dementia: Dementia With Lewy Bodies and Dementia in Parkinson’s Disease

Abstract

Parkinson’s disease with dementia (PD-D) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) may result from the same neurodegenerative process with different temporal and spatial courses. The authors report an association between DLB and family history of dementia in a comparison study between patients with a clinicopathological diagnosis of PD-D and DLB. Findings suggest that positive family history for dementia is associated with DLB with a yet unknown mechanism.

The relationship between Parkinson’s disease with dementia (PD-D) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) has been a subject of continuous debate over the last decade. Such debate is the consequence of considerable overlap between the two disorders. Although a consensus conference aimed to determine any distinction between PD-D and DLB by proposing diagnostic criteria for DLB, the etiopathologic relationship remains unknown.1,2 One explanation for such uncertainty may be the effort to define diseases as entities rather than processes. Both are “alpha-synucleinopathies” characterized by the presence of Lewy bodies (LBs) and probably share a common etiology. Although PD-D and DLB may result from the same process, clinical and neuropathological findings suggest different temporal and spatial courses. The influence of genetic or environmental factors in this temporo-spatial differentiation remains unknown. In an attempt to clarify the relationship between PD-D and DLB, we aimed to identify factors differentiating PD-D and DLB in a cohort of brain donors.

METHOD

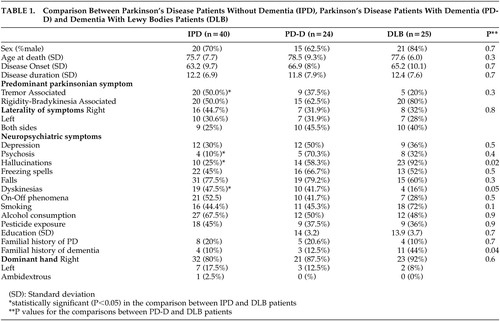

Our study population consisted of 25 DLB patients and 64 PD patients with (PD-D, N=24) and without (IPD, N=40) dementia. Seventy aged brain donors (C) without clinical or neuropathological evidence of neurologic disease were used as comparison subjects. All subjects consented during life to donate their brains to the University of Miami Brain Endowment Bank. Patients and comparison subjects were recruited and registered with the Brain Bank through a campaign performed throughout the United States over the last decade. All donors completed the Brain Bank’s registry form providing information about demographics, environmental exposures, personal and family history, activities of daily living, clinical and treatment details. For patients with cognitive impairment a caregiver with knowledge of the patient’s family and personal medical history completed the registry form.

The clinical diagnosis of PD, PD-D, or DLB was determined by either a movement disorders specialist or a neurologist before death and was clearly documented in the medical files. All diagnoses were confirmed after death by a movement disorders specialist (SP), who reviewed the medical files and applied the PD Society Brain Bank diagnostic criteria for PD3 and the consensus guidelines for the diagnosis of DLB.1 For a diagnosis of PD-D more than a 2-year history of parkinsonism preceding dementia was necessary. Diagnosis of dementia and psychiatric disorders (depression, visual hallucinations and psychosis) was made by the treating physicians according to established criteria4,5 and was clearly documented in the medical files. Clear documentation of dementia included diagnosis of dementia by a psychiatrist, formal psychometric testing and/or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).6 Retrospective chart analysis from movement disorders specialists is a well accepted method of case ascertainment, and has been frequently used in clinicopathological studies involving both parkinsonism and dementia including DLB.7–10 Family history of PD and dementia was reported by patients (if nondemented) and/or a person with knowledge of the subject’s family history (if demented). The clinical features were either documented as present or absent in case notes and/or patient registry forms. Donors with missing information (N=6) in any of the studied parameters were excluded.

All brains were formalin-fixed and sectioned according to the standard protocols.11 Apart from conventional staining, alpha-synuclein immuno-staining was used for the detection of LBs in cases with DLB and PD-D. Histological features for the pathological diagnosis of PD included depletion of pigmented neurons in the substantia nigra, with LBs in a proportion of surviving nigral neurons, and absence of features of other neurodegenerative diseases.3 The Consensus Pathological guidelines were used for the pathological diagnosis of DLB.12 Comparisons were made between patients with clinicopathological diagnosis of PD and clinical diagnosis of PD-D (PD-D) and patients with clinicopathological diagnosis of DLB as well as between patients with a clinicopathological diagnosis of PD without dementia (IPD) and DLB patients. Analyzed variables included demographic and clinical data, smoking and alcohol consumption, family history of PD (at least one first-degree with PD) and family history of dementia (at least one first-degree with dementia).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 11 0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). Mann-Whitney U test for two samples was used in nonparametric comparisons and Chi-square in the comparison of proportions. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. To account for confounding factors, multivariate analysis was performed using a stepwise logistic regression, submitting all covariates that showed statistical significance. Continuous variables were dichotomized using the median as the cutoff value. The study was approved by the local human subject research ethics committee.

RESULTS

The results of the comparison between PD, PD-D, and DLB patients are presented in Table 1. Demographic characteristics were similar between groups. There were no significant differences in parkinsonian symptoms between PD-D and DLB patients. Dyskinesias were significantly lower in DLB compared to PD-D (p=0.047) and IPD (p=0.02) patients. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms was similar in PD-D and DLB patients. A positive family history of PD was equally frequent in PD, PD-D, and DLB patients. However, a positive family history of dementia was about 4 times more frequent in patients with DLB than in patients with PD-D (p=0.034) and PD (p=0.04). The aged comparison subjects (C) had a mean age of 89.5 (SD = 7.9) years. In this group the family history of dementia was 9.9%. There was no significant difference in the family history of dementia between the C and PD-D or IPD patients. However, there was a significant difference in the prevalence of family history between C subjects and DLB patients (p=0.001). The comparison between IPD and DLB patients yielded more statistically significant differences: tremor was less predominant in the DLB group (p=0.03), and neuropsychiatric manifestations were more frequent in DLB patients (psychosis, p=0.026 and hallucinations, p<0.0001).

Multiple logistic analysis was performed to adjust family history of dementia and dyskinesias for age, sex, and disease duration in the comparison between PD-D and DLB patients. The relation remained significant after adjustment for both with an odds ratio (OR) of 15.54 (95%CI=2.13–113.54, p=0.007) and (OR) of 13.28 (95%CI=1.45–121.76, p=0.022), respectively.

DISCUSSION

Our objective was to identify differences between PD-D and DLB. Our data suggest that there is a positive association between DLB and family history of dementia in first-degree relatives. Dyskinesias were significantly lower in the DLB patients compared to the PD-D and PD patients. This may reflect differences in the sensitivity of these patients to dopaminergic medication. Another possible explanation is that DLB patients receive lower doses of dopaminergic medication due to increased psychiatric manifestations. All other comparisons between PD-D and DLB patients were not statistically significant. As expected, tremor was more common in IPD patients and neuropsychiatric manifestations were more common in DLB patients.

The mechanism by which positive family history of dementia could be related to the development of DLB is unknown. One could speculate that patients with LB pathology and positive family history of dementia may be genetically predisposed to different temporo-spatial distribution of the neurodegenerative changes in areas associated with dementia and/or impaired cognition (corticolimbic areas). In contrast to IPD, DLB is characterized by extensive extranigral LB formation, and depletion of acetylcholine neurotransmission, mainly in paralimbic and neocortical areas.2 It would be of interest if one could explore the association of a positive family history and the LB variant of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Family history of dementia has recently been identified as a novel and prominent risk factor for hallucinations in PD.13 In a community based study it was found that depression was more common in individuals with a positive versus negative family history of dementia in first degree relatives.14 A study on first-degree relatives of patients with probable AD suggested a possible relation between the presence of family history of dementia and development of cognitive impairment in disease-free adults.15

Our report has certain limitations commonly seen in retrospective studies. As it was based on chart review and donor registry forms and not on disease specific scales, the possibility for minor errors in the diagnosis of dementia in PD patients should be considered. On the other hand, diagnosis of dementia in DLB patients is relatively simpler since it is usually the presenting and prominent symptom or develops within a year after the diagnosis of parkinsonism. Another possible limitation of the present study is that family members were not examined for the presence of PD or dementia. It is known that patients with PD tend to overreport PD in their relatives when matched against comparison subjects.15 However, it is unknown whether DLB patients tend to overreport dementia in their relatives when matched against comparison subjects; therefore a classification bias cannot be excluded. Furthermore, although brain donors were recruited from the community there is a possibility of selection bias.

In summary, our findings suggest that positive family history for dementia is associated with DLB with a yet unknown mechanism. Family history for dementia may ascribe genetic susceptibility to corticolimbic regions, promoting different temporospatial spread of the neurodegenerative process in DLB. Similar associations have been made for hallucinations in PD and depression. Larger prospective studies are warranted to confirm our findings on the influence of family history in dementing syndromes with LBs. Additionally, family history of dementia may be worthy of monitoring in research of neuropsychiatric disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Brain Endowment Bank is funded in part by the National Parkinson Foundation (NPF).

This study was supported in part by grant NPF #662891 from the National Parkinson Foundation.

|

1 McKeith IG, D Galasko, K Kosaka, et al: Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology 1996; 475(5):1113–1124Crossref, Google Scholar

2 McKeith IG, DJ Burn, CG Ballard, et al: Dementia with Lewy bodies. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 2003; 81:46–57Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Hughes AJ, SE Daniel, L Kilford, et al: Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992; 55:181–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Psychiatric Disorders. Revised 3rd edition, ed. APA. 1987, Washington DCGoogle Scholar

5 APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition 1994, Washington DCGoogle Scholar

6 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Minimental state.” a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res1975; 12:189-198Google Scholar

7 Merdes AR, LA Hansen, DV Jeste, et al: Influence of Alzheimer pathology on clinical diagnostic accuracy in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2003; 60:1586–1590Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Jellinger KA, Seppi K, Wenning GK: Accuracy of diagnosis in dementia with Lewy bodies. Arch Neurol 2003.; 603:452Google Scholar

9 Jellinger KA: Influence of Alzheimer pathology on clinical diagnostic accuracy in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2004; 62(1):160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Litvan I, MacIntyre A, Goetz CG, et al: Accuracy of the clinical diagnoses of Lewy body disease, Parkinson’s disease, and dementia with Lewy bodies: a clinicopathologic study. Arch Neurol 1998; 55(7):969–978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Mirra SS, A Heyman, D McKeel, et al: The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part 2 Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 1991; 41(4):479–486Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 McKeith IG, Ballard CG, Perry RH, et al: Prospective validation of consensus criteria for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2000; 54(5):1050–1058Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Inzelberg R, Ramirez A, P Nisipeanu P, et al: Familial risk factors for hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2004; 19(suppl 9): 401Google Scholar

14 Harwood DG, WW Barker, RL Ownby, et al: Family history of dementia and current depression in nondemented community-dwelling older adults. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2000; 13(2):65–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Elbaz A, McDonnell SK, DM Maraganore, et al: Validity of family history data on PD: evidence for a family information bias. Neurology 2003; 61(1):5–6Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar