Subtle Neurological Deficits and Psychopathological Findings in Substance-Abusing Homeless and Non-Homeless Veterans

Abstract

This study evaluated the hypothesis that homeless individuals would display higher levels of neurological deficits than non-homeless individuals, particularly in frontal lobe or executive functions. Eighteen acutely homeless, 15 chronically homeless, and 20 non-homeless individuals admitted to an inpatient psychiatric service received a battery of neurological and psychosocial measures. In comparison to non-homeless subjects with comparable levels of psychopathology, homeless individuals showed higher levels of hostility, prior criminal activity, and family history of psychiatric illness, but lower levels of depression. A positive relationship between hostility and neurological soft signs was observed among chronically homeless subjects. These results suggest that a substantial subset of nonpsychotic homeless veterans suffers from “occult” neurological deficits.

Between 1985 and 1990 an estimated 8.5 million Americans experienced homelessness.1 Approximately 7.4% of all adult Americans (13.5 million) have encountered literal (street and shelter) homelessness in their lives.1 This figure represents a far larger estimate than those given in previous surveys on homeless populations.1

Homelessness is defined as the inability to secure regular housing when such housing is desired.2 The causes of homelessness are not well understood.3 Two groups of homeless people have been identified: chronically homeless (CH), and temporarily or acutely homeless (AH).2–4 The CH group also contains a complex subgroup of episodically or periodically homeless individuals who have been homeless at times and have been incapable of maintaining consistent employment or other prosocial responsibilities despite exposure to various opportunities.2,3,5

Homeless veterans constitute approximately 40% of the entire homeless population in the United States.6 Relative to other U.S. homeless populations, homeless veterans are more likely to be white and non-Hispanic, and they are likely to be better educated and to have higher levels of premorbid functioning.7 Most homeless patients suffer one or more psychiatric and personality disorders, including substance abuse, and a large number have a concurrent criminal record.8–12 There have been extensive studies and Department of Veterans Affairs resources addressing the problems of homeless veterans, but many programs have shown limited success.4,8,13–15 Disbursement of funds for personnel and domiciliary programs has failed to curtail the expansion of homelessness among veterans.4,8,13–15 Despite the temporary relief and ongoing support provided by these programs (in the form of psychiatric treatments, drug rehabilitation, domiciliary programs, and vocational rehabilitation), the majority of homeless veterans remain without adequate shelter and have significant mental disorders.4,6,13–15

The chronically homeless have shown impairment in the ability to organize, integrate, and execute complex goal-directed behaviors.13,14 These individuals often show difficulty in implementing and maintaining their treatment plans, resulting in noncompliance and early treatment termination.9,13,14 Impulsive, poorly planned and executed, dysfunctional behavior is typically found in neurologically compromised patients with frontoparietal or frontotemporal lobe lesions16–19 and is detectable through comprehensive neurological and neuropsychological evaluation.16 These so-called frontal lobe deficits interfere with the individual's executive functions, including accurate self-awareness for flexible response to changing environmental contingencies, task persistence or maintenance of a response set despite distraction, and creative problem solving.16 Clinical implications of these deficits are hypothesized to include an inability to interact with caseworkers, benefit from traditional psychosocial interventions, and profit from socioeconomic programs when provided.14,15 Identifying and characterizing executive dysfunctions in homeless veterans may guide development of more effective forms of rehabilitation and treatment for this population.17,20

Our review of the literature on cognitive deficits in homeless people revealed that low IQ is not associated with homelessness status, but it is associated with length of homelessness.21 This relationship was even stronger with IQ decrease than with current IQ. More important, cognitive deficits are more severe in mentally ill than in non–mentally ill homeless patients.22 These findings suggest that in addition to low IQ and mental illness, a third, neurological, factor may be causing homelessness.23

Although the nature of this relationship is unclear, several authors have proposed possible etiologies of CNS-mediated neuropsychiatric dysfunction—such as substance abuse-induced disorders, traumatic brain injury, epilepsy, schizophrenic or bipolar mood disorders, malnutrition, and HIV infection in homeless people.24–26 Moreover, one report has shown an even higher prevalence of HIV infection in a homeless mentally ill (9.6%) compared with a homeless control (5.4%) sample.27 However, available data did not address the possible effect of neurological impairment in nonpsychotic patients who are chronically homeless.24–27 The dearth of available adequately conducted research and the difficulty in assessing this population for neurological deficits prompted the present pilot study.

Our primary hypothesis was that a subset of chronically homeless patients would possess more subtle “frontal” neurological deficits than acutely homeless and non-homeless veterans. We also sought to identify psychiatric factors that are associated with homelessness among veterans and their possible relationship to neurological deficits.

METHODS

Subjects

Homeless subjects (n=33) were enrolled from consecutive admissions to one of the acute inpatient units of the Psychiatric Service at the Miami Veterans Affairs Medical Center after they self-reported a period of time during the previous 6 months in which stable housing was unavailable. Homeless subjects were further classified as acutely homeless (AH; n=18) and chronically homeless (CH; n=15) if the duration of homelessness was less than 1 month or exceeded 3 months, respectively. In order to recruit sufficient subjects, non-homeless patients (NH; n=20) who had previously been in our unit were also recruited from other units of the Psychiatry Service (e.g., the posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse units). All subjects in the study were therefore selected from an inpatient population, but at the time of the testing they were in different units. Patients meeting DSM-IV28 criteria for known primary psychotic disorders (such as dementia, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder) or suffering from known neurological conditions (such as seizure disorders, head injuries, encephalitis, and meningitis) were also excluded. All subjects were also assessed for a positive family history of psychiatric illness—operationally defined as prior alcohol or other psychoactive substance abuse, psychiatric hospitalization, or both—among parents or siblings.

After giving written informed consent and undergoing detoxification of at least 7 days' duration from psychoactive substances and stabilization of their psychiatric condition, subjects were administered an assessment battery measuring psychiatric symptomatology, personal and family history, neurological functioning, and HIV risk behavior while still in the inpatient units.

Procedures

The following instruments were used:

The Homelessness Questionnaire3 was used to assess the presence and duration of adult homelessness, as well as the incidence of childhood homelessness, foster care, and childhood criminal activity.

The HIV High Risk Behavior Questionnaire29 was used to determine HIV-related sexual and drug use behaviors over the last 10 years.

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)30 was used to evaluate general psychopathology using the following scores: 1) the total of all subscales; 2) the depression subscale (using the sum of emotional withdrawal, guilt feelings, and depressed mood); 3) the distress subscale (consisting of the sum of somatic concern, tension and anxiety items); and 4) the hostility subscale (as determined by summing the hostility and suspiciousness items). Rationale for the use of these subscales has been given elsewhere.30

The Quantified Neurological Scale (QNS),31 a 66-item instrument, was used to detect neurological impairment in the following domains: 1) overall cerebellar dysfunction; 2) frontoparietal deficits (extinction, graphesthesia, and astereognosis); 3) soft frontal lobe release signs (sequential task performance, overflow, and grasp and palmomental reflexes); and 4) overall neurological performance. This instrument has been shown to possess high interrater reliability.32 Most items were dichotomized to reflect absence (“0”) versus presence (“1,”); a subset were trichotomized as normal (“0,”), suggestive (“1,”), and abnormal (“2”).

A comprehensive chart review was also made to assess neurological, psychiatric, and psychosocial dysfunction. Charts were reviewed for documented history of head trauma (neurological exam, EEG, CT scan), criminal activity (number of felony charges and convictions), suicide attempts, and violent behavior; presence, length, and severity of substance use disorders; and family history of psychiatric disorders and of significant first- and second-degree criminal convictions.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. Following a significant ANOVA or chi-square finding, univariate post hoc paired t-tests were conducted to identify the source of significant differences between groups.

RESULTS

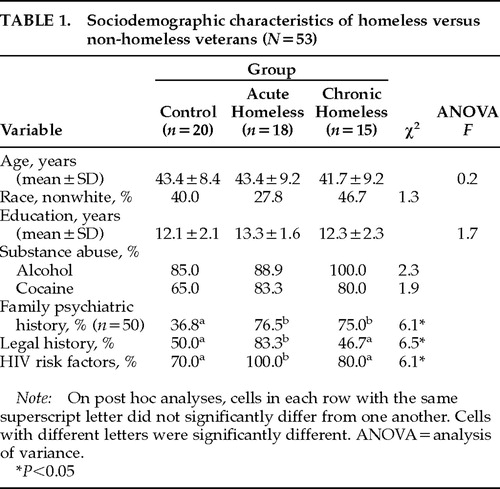

Sociodemographics of the sample (Table 1) did not significantly differ by group and included a mean age of 42.8 years, education of 12.6 years, ethnoracial composition of 38.2% nonwhite, alcohol abuse or dependence diagnosis of 91.3%, and cocaine abuse or dependence diagnosis of 76.1%. Homeless and non-homeless patients had comparable substance abuse histories as well as severity of psychopathology as reflected by the total BPRS scores. Several significant psychiatric and behavioral differences were shown between homeless and non-homeless subjects, as well as between CH and AH individuals. A greater number of AH and CH subjects, relative to control subjects, reported a positive family history of psychiatric illness (χ2=6.1, P=0.04). Homeless subjects reported more previous criminal behavior than non-homeless subjects (χ2=6.5, P<0.01), with AH indicating more criminal activity than CH.

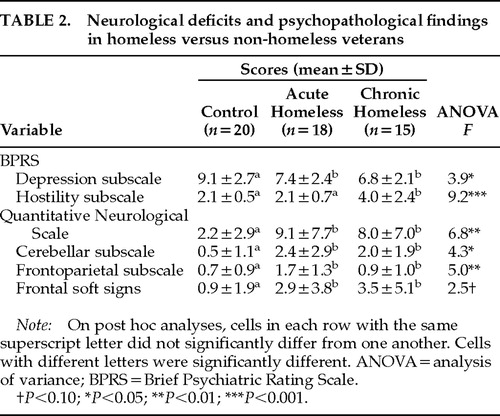

With respect to psychopathology (Table 2), control subjects scored significantly higher on the BPRS depression subscale than the homeless subjects. CH subjects scored significantly higher than the other two groups on the hostility subscale; the total BPRS score did not significantly differ between groups.

With respect to HIV risk behavior, AH subjects reported more risky behaviors than the CH and non-homeless control subjects (Table 1). However, post hoc Pearson's correlations did not show significant association between HIV risk status and neurological deficits.

Neurological functioning (Table 2) also differed among the groups. Relative to non-homeless subjects, homeless subjects exhibited greater numbers of neurological deficits. Areas of neurological impairment observed in both homeless groups included deficits in frontoparietal functions (graphesthesia, astereognosis, and extinction), and cerebellar functions as well as a trend for increased frontal lobe dysfunctions. No differences were indicated between AH and CH subjects on any of the neurological measures. Frontal soft signs were significantly correlated with higher levels of hostility (r=0.13, P<0.006). No other significant correlations between neurological and psychopathological variables were found.

DISCUSSION

Homeless and non-homeless patients have comparable severity of psychopathology as determined by BPRS scores, and, consistent with the study hypothesis, neurological impairments were shown among acutely and chronically homeless subjects relative to non-homeless control subjects. Contrary to expectation, subjects who were chronically homeless were not likely to show more neurological dysfunction than the acutely homeless. Since differences do not emerge between AH and CH, one might suggest that the neurological deficits are not secondary to the experience of homelessness, but rather are likely to precede and perhaps cause it.

Other researchers have shown that substance abuse diagnoses and family history of psychiatric illness are also important mediators of homelessness, a finding that concurs with those of the present study.33,34 The presence of frontal lobe release signs appears to influence hostility and violence32 and is a common pattern in violent individuals and those with impulse control disorders,33 suggesting a mechanism through which neurological deficits could affect interpersonal and criminal behavior and contribute to maintaining homelessness.35,36 Many hostile nonpsychotic psychiatric patients are treated with high doses of typical neuroleptics to control their violent behavior, resulting in severe neurological side effects (parkinsonism and akathisia) and reduced prosocial behavior.17,20 Finally, the importance of familial factors in contributing to both neuropsychiatric dysfunction and homelessness is suggested by the increased prevalence of family psychiatric history among homeless patients.33,34

The high level of HIV risk behavior across all groups strongly suggests the need for HIV prevention interventions among veterans seeking psychiatric treatment. The extremely high level among AH (100%) relative to the other groups suggests that individuals who have recently become homeless may comprise a subgroup requiring special attention.37 However, this study did not show any correlation between HIV risk behavior and neurological deficits. Unfortunately, HIV status was not uniformly known in the study population. In order to address the issue of cognitive decline in homeless people with HIV infection, more studies will have to be conducted.

Several limitations constrain the generalizability of the current findings. First, because the population consisted of nonpsychotic homeless male veterans receiving psychiatric treatment, the applicability of these results to nonveteran, female, nonpsychiatrically involved, and psychotic homeless individuals is uncertain. Second, homelessness was defined as unavailability of stable housing for the previous 6 months. This may or may not reflect typical housing patterns over a prolonged period. Third, data were collected by means of self-report, which may be subject to biases in recall, denial, or motivation to portray oneself in a certain manner. Fourth, the small sample size necessitates replication of the present findings with more hospitalized as well as nonhospitalized subjects. Finally, neuropsychological evaluation that might have detected more subtle patterns of dysfunction between AH and CH subjects was not conducted. The findings of the present study should be validated by use of a comprehensive neuropsychological battery that tests hypothesized mediators of the relationship between neurological dysfunction and homelessness.

Despite the limitations inherent in the present study, greater neurologic deficits were shown to correlate with level of hostility among homeless veterans. Future research for the development of more successful rehabilitation programs and psychopharmacological treatments (with beta-blockers, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and anticonvulsants) may prove to be beneficial in reducing homeless patients' impulsive and hostile behavior, which often leads to a high incidence of criminality, inability to participate in and benefit from treatment, and early termination.32–36,38,39

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Thomas Mellman for his critical review of the manuscript and his assistance in conducting this research.

|

|

1. Link BG, Susser E, Stueve A, et al: Lifetime and five-year prevalence of homelessness in the United States. Am J Public Health 1994; 84:1907–1912Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Vacha EF, Marin MV: Informal shelter providers: low income households sheltering the homeless. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless 1993; 2:117–133Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Susser E, Moore R, Link B: Risk factors for homelessness. Epidemiol Rev 1994; 15:546-556Google Scholar

4. Rosenheck R, Fontana A: A causal model of homelessness among male veterans of the Vietnam War generation. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:421–427Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Harris M: Treating sexual abuse trauma with dually diagnosed women. Community Ment Health J 1996; 32:371–385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Rosenheck R, Gallup P, Leda C: Vietnam era and Vietnam combat veterans among the homeless. Am J Public Health 1991; 81:643–646Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Rosenheck R, Koegel P: Characteristics of veterans and non veterans in three samples of homeless men. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:858–863Medline, Google Scholar

8. Geddes JR, Newton JR, Bailey S, et al: The chief scientist reports: prevalence of psychiatric disorder, cognitive impairment and functional disability among homeless people resident in hostels. Health Bull (Edinb) 1996; 54:276–279Medline, Google Scholar

9. Outcasts on Main Street: report of the Federal Task Force on Homeless and Severe Mental Illness. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services and Interagency Council on the Homeless, 1992Google Scholar

10. Lamb HR, Bachrach LL, Kass FL (eds): Treating the Homeless Mentally Ill: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1992Google Scholar

11. Winkleby MA, Fleshin D: Physical, addictive and psychiatric disorders among homeless veterans and non veterans. Public Health Rep 1993; 108:30–36Medline, Google Scholar

12. Martell DA, Rosner R, Harmon RB: Base-rate estimates of criminal behavior by homeless mentally ill persons in New York City. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:596–601Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bachrach LL: What we know about homelessness among mentally ill persons: an analytical review and commentary. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:453–464Medline, Google Scholar

14. Rosenheck R, Gallup P, Frisman LK: Health care utilization and costs after entry into an outreach program for homeless mentally ill veterans. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:1166–1171Medline, Google Scholar

15. Burns BJ, Santos AB: Assertive community treatment: an update of randomized trials. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:669–675Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Damasio AR, Anderson SW: The frontal lobes, in Clinical Neuropsychology, 3rd edition, edited by Heilman KM, Valenstein E. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993, pp 410–460Google Scholar

17. Jaeger J, Berns S, Tigner A, et al: Remediation of neuropsychological deficits in psychiatric populations: rationale and methodological considerations. Psychopharmacol Bull 1992; 28:367–390Medline, Google Scholar

18. Fogel BS, Goldscheider F, Royall D, et al: Cognitive Dysfunction and the Need for Long-term Care: Implications for Public Policy. Washington, DC, Public Policy Institute, American Association of Retired Persons, 1994Google Scholar

19. Royall DR, Mahurin RK, Gray KF: Bedside assessment of executive cognitive impairment: the Executive Interview. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40:1221–1226Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Campbell JJ III, Duffy JD, Salloway SP: Treatment strategies for patients with dysexecutive syndromes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:411–418Link, Google Scholar

21. Bremner AJ, Duke PJ, Nelson HE, et al: Cognitive function and duration of rooflessness in entrants to a hotel for homeless men. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:434–439Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Seidman LJ, Caplan BB, Tolomczenko GS, et al: Neuropsychological function in homeless mentally ill individuals. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:3–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Teesson M, Buhrich N: Prevalence of cognitive impairment among homeless men in a shelter in Australia. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:1187–1189Medline, Google Scholar

24. Kass F, Silver JM: Neuropsychiatry and the homeless. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1990; 2:15–19Link, Google Scholar

25. Williams JB, Rabkin JG, Remien RH, et al: Multidisciplinary baseline assessment of homosexual men with and without HIV-1 infection, II: standardized clinical assessment and lifetime psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:124–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. American Academy of Neurology AIDS Task Force (Working Group): Nomenclature and research definition for neurologic manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus–type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Neurology 1991; 41:778–785Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Townsend MH, Stock MS, Moore EV, et al: HIV, TB and mental illness in a health clinic for the homeless. J La State Med Soc 1996; 148:267–270Medline, Google Scholar

28. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

29. Volavka J, Convit A, O'Donnell J, Douyon R, et al: Assessment for risks behavior for HIV infection in psychiatric patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:482–485Medline, Google Scholar

30. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Res 1962; 10:799–812Google Scholar

31. Convit A, Volavka J, Czobor P, et al: Effect of subtle neurological dysfunction on haloperidol treatment in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:49–56Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Convit A, Jaeger J, Lin SP, et al: Prediction of violence in psychiatric inpatients, in Biological Contributions to Crime Causation, edited by Moffit T, Mednick S. Amsterdam, Martinus-Nijhoff, 1988, pp 223–245Google Scholar

33. Weitzman BC, Knickman JR, Shinn M: Predictors of shelter use among low income families: psychiatric history, substance abuse and victimization. Am J Public Health 1992; 82:1547–1550Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Shinn M, Knickman JR, Weitzman BC: Social relationships and vulnerability to become homeless among poor families. Am Psychol 1991; 46:1180–1187Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Dennis DL, Steadman HJ: The criminal justice system and severely mentally ill homeless persons: an overview. Paper prepared for the Federal Task Force on Homelessness and Severe Mental Illness, 1991Google Scholar

36. North CS, Smith EM, Spitznagel EL: Violence and the homeless: an epidemiologic study of victimization and aggression. J Trauma Stress 1994; 7:95–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Zolopa AR, Hahn JA, Gorter R, et al: HIV and tuberculosis infection in San Francisco's homeless adults. JAMA 1994; 272:455–461Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Solomon P, Draine J, Meyerson A: Jail recidivism and receipt of community mental health services. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994; 45:793–797Medline, Google Scholar

39. Lamb HR: Perspective on efficacy advocacy for homeless mentally ill persons. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:1209–1212Medline, Google Scholar