A Longitudinal Study of Psychosis due to a General Medical (Neurological) Condition

Abstract

A sample of 44 patients with a neurological disorder and a DSM-IV diagnosis of Psychosis due to a General Medical Condition were followed on average for 4 years and their response to treatment and clinical course noted. Outcome was more benign than in schizophrenia, with most patients having a brief duration of psychosis and good response to small doses of neuroleptics. One-fourth of patients suffered a single, brief psychotic episode with return to full premorbid function. None required maintenance neuroleptic treatment. The outcome and descriptive profile of the disorder also differed from late-onset schizophrenia. Thus, Psychosis due to a General Medical (Neurological) Condition does appear to have predictive validity. However, no temporal association was found between the neurological illness and psychosis. Possible reasons for this are discussed.

The DSM-IV1 diagnostic category “Psychosis due to a General Medical Condition” and the ICD-102 equivalent “Organic Delusional [Schizophrenia-Like] Disorder,” have stimulated critical comment with regard to terminology and diagnostic validity.3

There is evidence from a number of descriptive studies that in relation to schizophrenia, the condition has a later age of presentation (usually after age 35 years), an absence of family or personal history of psychosis, an increased frequency of visual and olfactory hallucinations, and a preservation of affective responses.4–6 Less clear are factors pertaining to predictive validity, including response to treatment, type of treatment, and measures of outcome. Similarly, when it comes to construct validity, research has been lacking. A fundamental premise is that the psychosis is etiologically related to the general medical condition. However, the DSM-IV makes no mention of what constitutes an appropriate time delay separating the two disorders, other than stating that there should be a temporal association between the onset, exacerbation, or remission of the medical condition and that of the mental disorder. Although it makes intuitive sense, this construct does not hold true in the single disorder that has been well studied, namely epilepsy.7,8 These uncertainties are reflected in the difficulty psychiatrists have in making the diagnosis. The category has a lower interrater reliability than other, less “organic” disorders—a reversal of the situation that associates greater diagnostic reliability with more severe forms of mental illness.3

The present study is consequently an attempt to address issues of predictive and construct validity by following the course of illness over a 4-year period in 44 patients with neurological disease and a diagnosis of Psychosis due to a General Medical Condition. Although results are directly applicable only to a subgroup of patients with this diagnosis (those with a neurological disorder), the study has broader diagnostic implications for the category as a whole.

METHODS

All patients met DSM-IV criteria for Psychosis due to a General Medical Condition, which includes having a medical illness, delusions and/or hallucinations, and an absence of delirium. For the purpose of this study the term “General Medical Condition” was restricted to a neurological disorder known to involve the brain. In all cases, the neurological disorder either preceded or coincided with the onset of psychosis.

Forty-four subjects were recruited from departments of neuropsychiatry at two sites: the Wellesley Hospital in Toronto and the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London. A single reviewer (A. F.) identified all subjects, either by direct interview (n=17) or retrospective chart review (n=27). Details of the retrospectively collected sample have been reported elsewhere as part of a study defining the phenomenology and imaging correlates of psychosis (schizophrenia-like and affective) associated with demonstrable brain disease.4 The 27 cases were selected from a group of 65 subjects if they fulfilled the criteria for Psychosis due to a General Medical Condition. In this regard, particular attention was paid to excluding patients with prominent and persistent mood symptoms.

Demographic data (age, gender, marital status, education, occupation, place of residence) and illness-related variables (neurological disorder, ages at onset of neurological and psychotic symptoms, respectively) were collected for each patient. Information on family history of mental illness was obtained from the patients' charts or, in the case of prospectively recruited patients, from the interview.

Follow-up data (mean duration of 47 months) were obtained on all cases. The course of the psychosis during the follow-up period was ascertained from patient interview, case note review, or contact with the treating physician (psychiatrist, neurologist, or family practitioner). Treatment variables (psychotropic drug, dosage and route of administration) were collected on the prospectively recruited cases. Residential and occupational outcome were determined as follows: patients living independently were assigned a good outcome, whereas those in nursing homes (for physical reasons) and psychiatric hospitals were rated as fair and poor, respectively. Occupational outcome was rated as good if subjects were employed and fair or poor if unemployed for physical or psychiatric reasons, respectively.9

There were no differences between the retrospectively and prospectively collected samples on demographic variables (gender: χ2=0, P=1; age: t=–0.9, P=0.4) or on illness-related variables (number of subjects who relapsed: χ2=1.2, P=0.4; Fisher's exact test).

Informed consent was obtained for all prospectively recruited subjects.

RESULTS

Demographics

The mean sample age (±SD) was 39.3±13.31 years. Twenty-five subjects (56.8%) were male, 26 (59.1%) were single, 9 (20.5%) were married, and 9 (20.5%) were either divorced or widowed.

Clinical Data

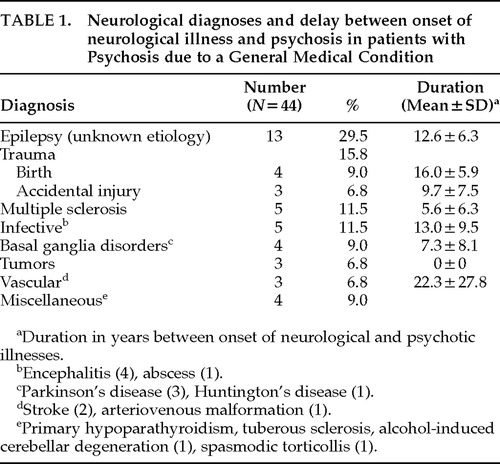

A wide array of neurological conditions was noted (Table 1), of which epilepsy of unknown etiology was the commonest, comprising almost one-third of the sample. A total of 28 patients (63.6%) suffered from seizures. The mean age at onset of neurological symptoms was 20.5±16.0 years (median=18.0; range 1–63).

The mean age at onset of psychosis was 32.2±13.5 years. The mean duration between onset of the neurological and psychotic symptoms was therefore 11.7±9.9 years (range 0–54). Dividing the sample into those with seizures (n=28) and those without seizures (n=16), the mean duration between onset of the neurological and psychiatric conditions was 12.5±7.4 years (median=12.5; range 0–25) and 6.1±5.7 years (median=4.5; range 0–16), respectively. A further breakdown of this interval according to specific neurological diagnosis is shown in Table 1. There was a family history of schizophrenia in a first-degree relative of 3 patients (6.8%).

Treatment

Twenty-eight subjects (63.6%) were followed up by psychiatrists, 9 received care from their family doctors, and 6 received no follow-up. A single psychiatric admission was required by 31 patients (70.5%), 10 (22.7%) required two psychiatric admissions, and a further 3 (6.8%) were admitted three times to a psychiatry ward.

Reliable information about treatment was available only on the 17 prospectively recruited patients. The most common neuroleptic prescribed was haloperidol, and dosages never exceeded 10 mg per day. When other neuroleptics were used, doses similarly did not exceed the haloperidol equivalent of 10 mg per day. Neuroleptic medication was often used for a brief period corresponding to the psychotic episode—usually a matter of weeks. In 2 cases the oral neuroleptic had been prescribed for more than 2 years. No patient was given a depot preparation.

Outcome

After a mean duration of 47±31.3 months (range 3–120), 3 patients had died from natural causes and 1 by suicide. Three patients had become demented, 1 was lost to follow-up, and 4 refused to be interviewed, although information was obtained on all 4 through contacts with the treating physician. Ten subjects (22.7%) had not experienced a psychotic relapse, 8 (18.1%) had been constantly psychotic, and 14 (31.8%) had been intermittently psychotic. The median duration of psychosis was accurately obtained only in the prospective recruited sample and was 16 days (range 2 days to 30 months).

Only 2 patients (4.5%) were residing in primarily psychiatric accommodation. Thirty-two (72.7%) were living independently, and 5 (including the 3 patients with dementia) were in nursing homes.

Excluding the patients who either died, became demented, refused follow-up, or were lost to follow-up (n=8), 10 (22.7%) had returned to their premorbid work level, and 12 (27.3%) were unable to work for reasons that were primarily psychiatric. Neurological difficulties precluded the rest of the sample from working.

Gender Comparisons

The mean age at onset of psychosis for male subjects was 33.4±13.4 years, and for females it was 30.6±13.8 years; this difference did not prove statistically significant (t=0.69, df=42, P=0.5). Similarly, there were no differences between the age at onset of neurological symptoms between males (22.1±15.9 years) and females (18.5±16.4 years; t=0.7, df=41, P=0.5). Furthermore, there were no gender differences with regard to a history of birth trauma (χ2=3.4, df=1, P=0.1), marital status (χ2=3.0, df=3, P=0.4), or premorbid psychiatric history (χ2=3.6, df=3, P=0.3). Male subjects were not more likely to have a psychotic relapse (χ2=1.8, df=1, P=0.2), require more contact with a psychiatrist during follow-up (χ2=0.5, df=1, P=0.5), or have more frequent psychiatric admissions (χ2=4.2, df=3, P=0.2). Males were not more likely to have seizures (χ2=2.0, df=1, P=0.4). In addition, outcome with respect to occupation (χ2=1.6, df=1, P=0.2) and place of residence (χ2=3.9, df=3, P=0.3) did not differ.

DISCUSSION

Forty-four patients with varying neurological disorders meeting the DSM-IV criteria for a diagnosis of Psychosis due to a General Medical Condition were assessed clinically and with respect to a number of treatment and outcome variables. The DSM-IV criteria embrace a wide array of medical illnesses, with the tacit assumption of potential brain involvement in each. However, the inability to clearly demonstrate this other than by the presence of psychosis raises questions about inferred etiology. The unique composition of the present sample partly overcomes this problem by including only patients with neurological disorders known to involve the brain. Although the chance occurrence of both psychosis and such a neurological disorder still cannot be ruled out, the exclusion of cases in which the psychosis came first further increases the likelihood of a causal relationship.

We did not, however, find a temporal association between the two conditions. A review of the neuropsychiatric literature reveals a paucity of data in this regard, and only in relation to seizure disorders has a consistent picture emerged. The mean duration of 13 years separating the onset of seizures from psychosis in our sample approximates the figure of approximately 14 years reported previously.10,11 Although the duration for non–seizure disorders was shorter, a mean of 6 years (median of 4 years) had still elapsed before delusions and hallucinations began. The further breakdown of these data according to neurological disorder is difficult to interpret because of small numbers and ascertainment bias. Nevertheless, these figures highlight the fact that psychosis, at least in regard to neurological disease with brain involvement, often begins many years later.

An analogous situation exists in patients who become psychotic after temporal lobectomy.12 Why this should be is unclear, but a study of psychiatric disorders in metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD), which frequently includes psychosis, may provide a clue to this time lag.13 Although the pattern and nature of the cerebral lesions are not age-specific and encompass a wide age range (early childhood to late adulthood), psychosis clusters in the age group 12 to 30 years. As the disease process in MLD progresses and patients age, psychosis resolves, leaving cognitive and neurological deficits as the predominant finding. It is therefore postulated that psychosis requires the pathological function of some brain structures accompanied by intact function of others. A number of years have to elapse before such a state is reached; hence the delay between the onset of the neurological and psychotic symptoms. This explanation may also hold for some of the other neurological disorders included in our study. Conversely, there is recognition that in certain conditions such as Huntington's disease14 and Lewy body dementia,15 psychosis may coincide with, or even predate, the onset of neurological symptoms. In our sample, the broad range (0–16 years) of intervals separating the two conditions attests to the difficulty in establishing a single time frame appropriate to diverse conditions.

Our study does, however, support the notion that Psychosis due to a General Medical Condition may have predictive validity. In the 17 patients for whom prospective treatment data were available, without exception, moderate to small doses of neuroleptics were used. This is in keeping with a trend toward smaller doses of neuroleptic medication in the treatment of schizophrenia.16 Treatment diverged, however, when it came to depot medication and the use of oral maintenance treatment, neither of which was routinely employed in our sample. Although there are no treatment trials supporting our approach, the transient nature of the psychosis in the majority of patients suggests that it has merit. With regard to outcome, most patients recovered from their index psychotic episode, and although their relapse rate was high, all patients subsequently recovered from these episodes, too. Significantly, almost a quarter of patients never experienced a relapse.

The mean duration of follow-up fell 1 year short of 5 years, at which point outcome measures in schizophrenia tend to stabilize.17 We therefore cannot draw definite conclusions, but the relatively benign course of the psychosis in relation to schizophrenia is further supported by the good residential and occupational outcomes in our sample. Regarding the latter, it could be argued that if inability to work because of neurological disability is put to one side, the number of patients unable to work for psychiatric reasons alone (55%) approaches that for schizophrenia. However, patients who were able to return to work (45%) almost invariably did so at their premorbid level, as opposed to entering the sheltered work environment frequently associated with schizophrenia. The brief duration of psychotic symptoms18 and, perhaps more important, the paucity of negative symptoms19 could account for this. Reviewing all the outcome criteria, the picture to emerge is therefore one that differs from schizophrenia. On average, the brief duration of psychosis and rapid response to low dose neuroleptic medication, the fact that patients did not generally require maintenance neuroleptic treatment, more specifically depot neuroleptics, and the return of a substantial number of patients to their premorbid work level set the disorder apart from the more pernicious outcome associated with schizophrenia.

With a mean age of psychosis onset that was a decade older than that of patients with a first-break schizophrenic illness,20 our sample resembled to some extent patients with late-onset (>45 years) schizophrenia.21 However, patients in the late-onset group have a premorbid history of schizoid and paranoid personality traits, and the majority are female, neither of which was the case in our sample. Further exploration of the gender differences failed to replicate the usual picture seen in schizophrenia, wherein males present at a younger age22,23 and have greater premorbid abnormalities24 and a poorer outcome.25

We can comment only tentatively on the role of genetic factors in the pathogenesis of the psychosis in our sample because numbers were small and data were not age corrected. The prevalence figure in our sample of 6.8% for schizophrenia in a first-degree relative is intermediate between lifetime prevalence figures for the general population and that for patients with schizophrenia.

In summary, the majority of patients with Psychosis due to a General Medical Condition respond quickly to low-dose neuroleptic treatment, and their psychotic illness runs a more benign course than that seen in patients with schizophrenia. These facts establish a degree of predictive validity. Furthermore, the absence of premorbid personality traits (schizoid, schizotypal, paranoid) and the findings of an age of presentation intermediate between schizophrenia and late-onset schizophrenia, equal gender prevalence, and no differences between males and females regarding age of psychosis onset and course and medium-term outcome further enhance the distinct status of this diagnosis.

On the negative side, we failed to find a clear temporal association between neurological illness and psychosis, even when seizure disorders were excluded. Our data plus findings from the seizure/psychosis literature7,10,11 consistently demonstrate a substantial period (years) elapsing before psychosis presents. Given that our sample composition was restricted to patients with neurological illness, we cannot apply this conclusion to the broader DSM-IV category of all medical illnesses. Nevertheless, the robustness of the finding suggests that for future versions of the DSM and ICD it will be necessary to reconsider the question of a temporal association. Abandoning the construct, however, may leave psychiatrists even more unsure of their diagnosis. Prospective studies embracing an array of medical conditions will help clarify the issue.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The results of this study were presented at the American Neuropsychiatric Association annual meeting, Pittsburgh, PA, October 12–15, 1995.

|

1. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

2. World Health Organization: The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1992Google Scholar

3. Lewis SW: ICD-10: a neuropsychiatrist's nightmare? Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:157–158Google Scholar

4. Feinstein A, Ron MA: Psychosis associated with demonstrable brain disease. Psychol Med 1990; 20:793–803Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Cummings JL: Organic delusions: phenomenology, anatomical correlations and review. Br J Psychiatry 1985; 146:184–197Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Perez MM, Trimble MR: Epileptic psychosis: diagnostic comparison with process schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1980; 137:245–249Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Trimble MR: The schizophrenia-like psychoses of epilepsy. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1992; 5:103–107Google Scholar

8. American Psychiatric Association: DSM-IV Sourcebook. Washington, DC. American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

9. Tsuang MT, Woolsen RF, Fleming AJ: Long term outcome of major psychoses, I: schizophrenia and affective disorders compared with psychiatrically symptom free surgical conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 39:1295–1301Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Slater E, Beard AW, Glithero E: The schizophrenia-like psychoses of epilepsy. Br J Psychiatry 1963; 109:95–150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Davison K, Bagley CR: Schizophrenia-like psychoses associated with organic disorders of the central nervous system: a review of the literature, in Current Problems in Neuropsychiatry, edited by Herrington R. Ashford, UK, Hedley, 1969, pp 113–184Google Scholar

12. Mace C, Trimble MR: Psychosis following temporal lobe surgery: a report of six cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1991; 54:639–644Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hyde TM, Ziegler JC, Weinberger DR: Psychiatric disturbance in metachromatic leukodystrophy. Arch Neurol 1992; 49:401–406Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Cummings JL: Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms associated with Huntington's disease, in Behavioral Neurology of Movement Disorders, edited by Weiner W, Lang A. New York, Raven, 1995, pp 179–186Google Scholar

15. McKeith IG, Galasko D, Wilcock GK, et al: Lewy body dementia: diagnosis and treatment. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167:709–717Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Hirsch SR, Barnes TRE: Clinical use of high-dose neuroleptics. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:94–96Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Keith SJ, Mathews SM: The diagnosis of schizophrenia: a review of onset and duration issues, in DSM-IV Sourcebook, edited by Widiger TA, Frances H, Pincus H, et al. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 393–418Google Scholar

18. Helzer JE, Kendell RE, Brockington RF: Contributions of the six month criterion to the predictive validity of the DSM-III definition of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:1277–1280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Hargreaves W, Kane JM, Ninan PT: Treatment Strategies in Schizophrenia Collaborative Study Group: demographic characteristics, treatment history, presenting psychopathology, and early course in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull 1990; 25:340–343Google Scholar

20. Lieberman JA, Alvir J, Woerner M, et al: Prospective study of psychopathology in first episode schizophrenia at Hillside Hospital. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:351–371Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Harris MJ, Jeste D: Late onset schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull 1988; 14:39–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sartorius N, Jablensky A, Korten A, et al: Early manifestations and first-contact incidence of schizophrenia in different cultures. Psychol Med 1986;16:609–628Google Scholar

23. Goldstein JM, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV: Gender and schizophrenia: implications for understanding the heterogeneity of the illness. Psychiatry Res 1989; 28:243–253Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Torrey EF, Taylor E, Bracha HS, et al: Prenatal origin of schizophrenia in a subgroup of discordant monozygotic twins. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:423–432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Angermeyer MC, Goldstein JM, Kuhn L: Gender differences in schizophrenia: re-hospitalisation and community survival. Psychol Med 1989; 19:365–382Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar