Clozapine Restores Water Balance in Schizophrenic Patients With Polydipsia-Hyponatremia Syndrome

Abstract

Hyponatremia/hypoosmolemia causes marked morbidity and prolongs hospital stays in a significant subset of schizophrenic patients. Case reports with methodological limitations suggest clozapine ameliorates this water imbalance. To more conclusively assess this possibility, we completed a 24-week open-label study in 8 male polydipsic hypoosmolemic schizophrenic inpatients. Subjects were treated initially for 6 weeks with a conventional neuroleptic, which was replaced by 300, 600, and 900 (if tolerated) mg/day of clozapine for sequential 6-week periods. On clozapine, mean plasma osmolality rose an average of 15.2 mosm/kg (95% CI : 5.5–25.0). Dosage of 300 mg/day of clozapine was sufficient to normalize plasma osmolality and was generally well tolerated. Clozapine appears to be the first effective pharmacotherapy for severe water imbalance in schizophrenia.

Episodic water intoxication occurs in 3% to 5% of chronic schizophrenic patients requiring long-term care and may be manifested by delirium, seizures, coma, and even death.1 The signs and symptoms are primarily a consequence of acute brain swelling, which is a product of the as yet unexplained polydipsia these patients exhibit and of their reduced free-water clearance.2,3 Both the relatively modest, but chronic, dilutional hyponatremia and the episodic life-threatening water intoxication have been resistant to many pharmacologic interventions. Targeted fluid restriction in carefully monitored settings has been the cornerstone of most current regimens,4 and as a result many of these patients occupy long-term psychiatric beds.

Although an initial report suggested the atypical neuroleptic clozapine induces hyponatremia in some schizophrenic patients,5 many subsequent reports indicated it ameliorates water imbalance.6–14 Of the 36 patients treated with clozapine described in these nine reports, 4 patients appear to have derived little benefit,8,12 5 others exhibited polydipsia alone (that is, they never had documented hyponatremia/hypoosmolemia),7,8,11,14 and in 7 others the effect of clozapine was difficult to assess.9,12,14 Of the remaining 20 improved patients, 16 showed no evidence of water intoxication over fairly prolonged follow-up periods (≥6 months),8,10,12,14 but the frequency of water intoxication prior to clozapine was not stated. Only 4 of the 36 treated patients had documented hyponatremia/hypoosmolemia either immediately prior to starting6,7 or after stopping7,13 clozapine but not while taking it. Furthermore, in only 2 of these 4 cases could the incidence of symptomatic water imbalance be accurately estimated prior to clozapine, and only 1 of these 2 (therefore only 1 of the 36 total) was studied in a prospectively designed trial.7 Thus, although clozapine likely ameliorates symptomatic hyponatremia in at least some schizophrenic patients, it is impossible to be certain because of the absence of sufficient baseline data for this episodic disorder, the lack of objective outcome measures, and the retrospective reporting.

To further clarify the effects of clozapine on water imbalance in schizophrenia, we implemented a prospective open-label trial comparing three fixed doses of clozapine to conventional neuroleptic treatment. Data from the prior reports were not sufficient to generate a hypothesis regarding a dose effect, so we simply predicted that plasma osmolality would be higher with clozapine than with conventional neuroleptic treatment.

METHODS

Subjects

The initial subjects were 10 male hyponatremic inpatients (plasma sodium <125 mEq/l in the previous month) on extended treatment units at Illinois state psychiatric facilities. Each met the criteria for treatment-resistant schizophrenia (DSM-III-R), and none had medical illnesses or was taking other medications known to influence water balance.4 Each was considered competent to consent by professional staff unaffiliated with the research program, and each provided written informed consent after the procedures had been fully explained.

Procedures

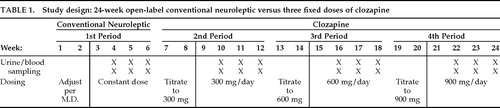

The study lasted 24 weeks and encompassed four sequential 6-week periods (Table 1). For the first 2 weeks of the first period, the dose of a conventional neuroleptic (haloperidol, n=4; thiothixene, n=3; loxapine, n=1) was adjusted by the treating clinician to minimize psychopathology. All other medications, except benztropine for parkinsonism, were discontinued. From week 3 through week 6, dosage was held constant. Spot plasma and urine samples were obtained on the same weekday, twice weekly at 8:00 a.m., during weeks 4, 5, and 6. Only subjects with at least one plasma osmolality <270 mosm/kg (corresponding to plasma sodium of about 130 mEq/l or less) were continued into the second period (n=8).

At the start of the second period the conventional neuroleptic was abruptly discontinued, and clozapine was titrated upward to 300 mg/day over the next 2 weeks (Table 1). After one additional week at 300 mg/day, blood and urine samples were obtained over 3 weeks as described above. In a similar manner, during the third and fourth periods clozapine was titrated to 600 and then to 900 mg/day, respectively, and sampling was repeated as described earlier. This regimen was based on the dosing recommendations of the drug manufacturer at the time the study was started. Two of the 8 subjects did not receive the highest dose of clozapine because of excess sedation while receiving the 600 mg/day dose, and thus they completed only 18 weeks of the study.

Throughout the study, water intoxication was prevented with a target weight procedure in which fluid restriction was imposed after either rapid marked weight gain or signs of symptomatic hyponatremia (confusion, vomiting, tremor, ataxia) were observed.4 To explore the effect of clozapine on psychopathology, the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale was completed by trained raters (intraclass correlation coefficient 0.84) during the first period (on conventional neuroleptics) and at least once while 7 of the subjects were on clozapine.

Laboratory and Statistical Analyses

Blood and urine samples were analyzed for plasma and urine osmolality, respectively, by freezing point depression (Advanced Instruments 2-D Osmometer, Needham, MA; coefficient of variation <1.2%). Plasma and urine osmolality and BPRS scores were averaged for each of the four treatment periods for each subject. We chose to measure plasma osmolality, rather than the more familiar plasma/serum sodium concentration, because of the potentially smaller measurement error. Sodium concentration can be approximated by applying the following formula: [Na+]≈(Posm−10)/2.

To examine the effect of clozapine on parameters of water balance and on psychopathology we relied on a mixed model analysis of variance (fixed effect=period, random effect=subject; SPSS-PC, Chicago, IL). The nature of significant findings was further examined with a priori Helmert contrasts (expressed as t-statistics). The first contrast (H1) compares the first treatment period with the mean of the second through fourth periods; the second (H2) compares the second treatment period with the mean of the third and fourth periods; and the last (H3) compares the third and the fourth periods.

To establish the significance of dichotomous outcomes (for example, number of subjects with plasma osmolality <260 mosm/kg while on standard neuroleptic versus while on clozapine), we relied on McNemar's test, which assesses the change in dichotomous outcomes across two periods. Since we were only interested in a reduction in adverse outcomes with clozapine treatment, use of this test reflects a very conservative approach to the data, as the period on clozapine was three times longer than that on standard neuroleptic.

RESULTS

Effect on Plasma Osmolality

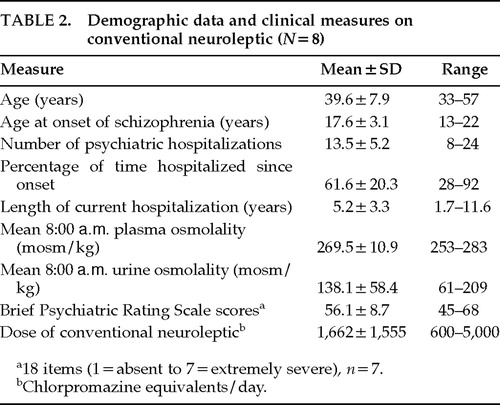

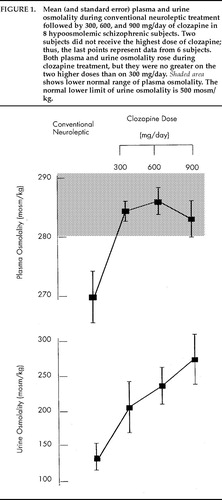

Table 2 displays demographic and clinical data for the 8 subjects who exhibited hypoosmolemia during the first sampling period. Plasma osmolality on clozapine rose an average of 15.2 mosm/kg above the subjects' mean values on conventional neuroleptic (range 1.9 to 33.6 mosm/kg, 95% CI 5.5, 25.0 mosm/kg; mixed-model ANOVA, F=7.09, df=3,26, P<0.001; H1 t=4.54, P<0.001; Figure 1). Plasma osmolality normalized on 300 mg/day, and the two higher doses had no further effect (H2: P=0.19). On conventional neuroleptic, 26 of the 47 plasma samples were <270 mosm/kg, whereas all 141 plasma samples obtained in the second through fourth periods were above this level (McNemar's test, df =1, P<0.005). Furthermore, 11 of these 26 values on standard neuroleptics (in 5 of the subjects) were <260 mosm/kg (McNemar's test, χ2=5, df=1, P=0.03). Nine instances (in 4 subjects) of fluid restriction were imposed per the target weight procedure during the 6 weeks of conventional neuroleptic treatment, but no fluid restrictions were required during the 18 weeks of clozapine treatment (McNemar's test, χ2=4, df=1, P<0.05).

Other Effects of Clozapine

Morning urine osmolality also increased during clozapine treatment (mixed model ANOVA, F=4.28, df =3,26, P=0.02; H1: t=3.2, P<0.01; Figure 1), which suggests that fluid intake had diminished. Although the display in Figure 1 suggests that higher doses showed further salutary effects, these did not approach statistical significance (H2: P=0.75; H3: P=0.37).

Besides the excessive sedation in 2 subjects, 1 subject suffered a seizure shortly after starting clozapine. His weight did not exceed his target limit, and his plasma osmolality was above 260 mosm/kg immediately after the seizure. Valproic acid was subsequently added to his clozapine regimen. Elimination of this subject from the data analysis did not alter the significance of the major findings. Total BPRS scores (mean±SD: first period, 57±9; second period, 60±17; third period, 47±9; fourth period, 51±3; F=1.63, df =3,17, P=0.22) and positive or negative symptom factors were not significantly different with clozapine treatment.

Poststudy Outcome

All 8 subjects were discharged from the hospital on clozapine within 3 months of completing the study. Since discharge (mean duration of follow-up 19.9 months, range 7 to 30), 7 of the 8 subjects have not suffered from water intoxication. The eighth subject was switched to risperidone by his treating physician upon discharge and then spent all but 8 of the next 29 months back in the hospital. The other 7 patients remained on clozapine, and only 1 required rehospitalizaton (on two separate occasions for 3 weeks for behavioral problems). These 8 patients had spent a great portion of their adult lives in a hospital, and prior to discharge had been continuously hospitalized for an average of 5 years (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study supports the use of clozapine in the treatment of water intoxication in schizophrenia because we have demonstrated that plasma osmolality increased significantly with clozapine treatment, that levels rose in all subjects, and that episodes of hypoosmolemia and the need for fluid restriction were eliminated. Although many case reports have previously suggested clozapine improves water imbalance in schizophrenia, this is the first prospectively designed study to investigate the issue. A two-stage selection process and the use of several objective outcome measures, gathered over a relatively extended period of time, are the other major positive attributes of this study.

Although several patients complained of sedation, only 1 experienced a significant adverse event: a seizure shortly after starting clozapine. This patient was not markedly hypoosmolemic at the time of the seizure, although this does not exclude the possibility that water intoxication was entirely responsible.4 It seems more likely that the seizure was due in part to the adverse effect of clozapine on the seizure threshold; thus, clinicians may want to consider prophylactic anticonvulsants until the water balance has normalized.

The implications of our findings are limited by the small sample size, the absence of female subjects, the brief (6-week) baseline period for this episodic disorder, the absence of afternoon measures (when the water imbalance is usually more severe4), and the open-label nonrandomized design. A study without any such limitations would require relatively heroic measures on the part of investigators, subjects, and staff. The fact that other studies have by and large shown that other pharmacologic interventions are ineffective for this disorder4,15 makes it unlikely that our and other investigators' findings that clozapine ameliorates water imbalance can be attributed to these limitations. Our unexpected finding that the subjects, who on average had been hospitalized for more than 60% of their adult lives and continuously for more than 5 years prior to the study, were discharged from the hospital and stayed out (if they remained on clozapine) provides further support for the clinical significance of the findings. We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that improved care on the clinical research unit was also an important factor.

Our findings indicate that plasma osmolality normalizes on 300 mg/day clozapine, and thus higher doses would not be expected to have further effects. The efficacy of even lower doses,7 the value of determining clozapine plasma levels, and the efficacy of other agents, such as olanzapine,16,17 remain to be determined. The available data, however, do not conclusively address the issue of whether higher doses would further increase urine osmolality (which was still below the lower limit of normal) or contribute to the overall positive clinical outcome. Further studies with a larger sample size in which dose and time effects can be teased apart are needed to address these issues.

The mechanism of the improved water balance remains unclear. Although conventional neuroleptics can adversely influence water balance,18,19 it seems more likely that clozapine, per se, exerts a salutary effect, considering that 1) neuroleptic exposure is no greater in hyponatremic than in other schizophrenic patients on extended treatment units1,19 (nor is hyponatremia associated with tardive dyskinesia20); 2) polydipsia, hyponatremia, and water intoxication were documented prior to the neuroleptic era, as well as in the current era, in patients off neuroleptics for long periods;1,3,4 3) reduction of neuroleptic dose does not improve, and usually worsens, hyponatremia;4,21 4) neuroleptics do not enhance antidiuretic hormone secretion;4 and 5) plasma sodium and clozapine levels have been reported to be positively correlated in schizophrenia.22 The data suggest that the restoration of water balance is at least partly attributable to decreased intake, which in turn is not simply a consequence of improved psychopathology. Further studies are needed to clarify this issue, as well as whether clozapine normalizes free-water clearance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Marie Simmons, L.P.N., Sue Barnett, R.N., Nijole Grazulis, M.S., Diane McGuire, B.A., William Briska, M.S.W., Barbara Jones, M.S., Don Hedeker, Ph.D., Miljana Petkovic, M.S., Jim Peterson, B.A., Ed Altman, Ph.D., and the staffs of The Psychiatric Institute, Chicago, IL, and Elgin Mental Health Center, Elgin, IL. Preliminary data were presented at the Vth International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, Warm Springs, VA, April 11, 1995.

|

|

FIGURE 1. Mean (and standard error) plasma and urine osmolality during conventional neuroleptic treatment followed by 300, 600, and 900 mg/day of clozapine in 8 hypoosmolemic schizophrenic subjects. Two subjects did not receive the highest dose of clozapine; thus, the last points represent data from 6 subjects. Both plasma and urine osmolality rose during clozapine treatment, but they were no greater on the two higher doses than on 300 mg/day. Shaded area shows lower normal range of plasma osmolality. The normal lower limit of urine osmolality is 500 mosm/kg.

1 de Leon J, Verghese C, Tracy JI, et al: Polydipsia and water intoxication in psychiatric patients: a review of the epidemiological literature. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 35:519–530Google Scholar

2 Goldman MB, Luchins DJ, Robertson GL: Mechanisms of altered water metabolism in psychotic patients with polydipsia and hyponatremia. N Engl J Med 1988; 318:397–403Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Goldman MB, Robertson GL, Luchins DJ: Psychotic exacerbations and enhanced vasopressin secretion in schizophrenics with hyponatremia and polydipsia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:443–449Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Vieweg WVR: Treatment strategies in the polydipsia hyponatremia syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:154–160Medline, Google Scholar

5 Ogilvie AD, Cory MF: Clozapine and hyponatremia (letter). Lancet 1992; 340:672Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Gupta S, Baker P: Clozapine treatment of polydipsia. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1994; 6:135–137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 de Leon J, Verghese C, Stanilla JK, et al: Treatment of polydipsia and hyponatremia in psychiatric patients: can clozapine be a new option? Neuropsychopharmacology 1995; 12:133–138Google Scholar

8 Lyster C, Miller AL, Seidel D, et al: Polydipsia and clozapine. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994; 45:610–611Medline, Google Scholar

9 Munn NA: Resolution of polydipsia and hyponatremia in schizophrenic patients after clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:439–440Medline, Google Scholar

10 Henderson DC, Goff DC: Clozapine for polydipsia and hyponatremia in chronic schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:768–770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Lee HS, Swon KY, Alphs LD, Meltzer HY: Effect of clozapine on psychogenic polydipsia in chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991; 11:222–223Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Spears MN, Leadbetter RA, Shutty MS: Clozapine treatment in polydipsia and intermittent hyponatremia. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:123–128Medline, Google Scholar

13 Wakefield T, Colls I: Clozapine treatment of a schizophrenic patient with polydipsia and hyponatremia. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:445–446Medline, Google Scholar

14 Fuller MA, Jurjus G, Kwon K, et al: Clozapine reduces water-drinking behavior in schizophrenic patients with polydipsia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 16:329–332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Millson RC, Emes CE, Glackman WG: Self induced water intoxication treated with risperidone. Can J Psychiatry 1996; 41:648–650Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Richelson E: Preclinical pharmacology of neuroleptics: focus on new generation compounds. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57 (suppl 11):4–11Google Scholar

17 Littrell KH, Johnson CG, Littrell SH, et al: Effects of olanzapine on polydipsia and intermittent hyponatremia (letter). J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:549Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Lawson WB, Karson CN, Bigelow LB: Increased urine volume in chronic schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Res 1985; 14:323–331Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Goldman MB, Robertson GL, Luchins DJ, et al: The influence of polydipsia on water excretion in hyponatremic, polydipsic schizophrenic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81:1465–1470Medline, Google Scholar

20 Umbricht DS, Saltz B, Pollack S, et al: Polydipsia and tardive dyskinesia in chronic psychiatric patients: related disorders? Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1536–1538Google Scholar

21 Canuso CM, Goldman MB: The effect of neuroleptic reduction on plasma sodium in hyponatremic polydipsic schizophrenics. Psychiatry Res 1996; 63:227–229Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Spigset O, Hedenmalm K: Hyponatremia during treatment with clomipramine, perphenazine, or clozapine: study of therapeutic drug monitoring samples. J Clin Psychopharmol 1996; 16:412–414Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar