Sertraline in the Treatment of Major Depression Following Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

Abstract

An 8-week, nonrandomized, single-blind, placebo run-in trial of sertraline was conducted on 15 patients diagnosed with major depression between 3 and 24 months after a mild traumatic brain injury. On the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, 13 (87%) had a decrease in score of ≥50% (“response”), and 10 (67%) achieved a score of ≤7 (“remission”) by week 8 of sertraline. There was statistically significant improvement in psychological distress, anger and aggression, functioning, and postconcussive symptoms with treatment.

Depression has been shown to be a common sequela of traumatic brain injury (TBI) in both inpatient and outpatient populations.1 Although most studies have included a majority of patients with moderate to severe injuries, patients with mild injuries also appear to have an increased risk for depression after TBI.2 Patients with TBI and subsequent depression have greater functional disability and postconcussive symptoms and perceive their injury as more severe than do those without depression.3

Studies in other medical and neurological populations have shown that treating depression can be effective and can decrease functional impairment, somatic symptoms, and perception of impairment. A few studies have examined the efficacy of antidepressants in the treatment of depression following TBI.4–8 However, few have focused on those with mild TBI or have examined whether treatment decreases functional disability and postconcussive symptoms.

The goals of this study were to determine if treating major depression following mild TBI with sertraline, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, is associated with decreases in 1) symptoms of depression, 2) psychological distress, 3) functional disability, and 4) postconcussive symptoms.

METHODS

Subjects were 16 consecutive ambulatory respondents to advertisements in local newspapers, health magazines, and head injury support groups who had sustained a mild closed TBI within the past 3 to 24 months. Mild TBI was determined by using the criteria set forth by the Head Injury Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine9 and is defined as manifested by at least one of the following: a) any period of loss of consciousness of 30 minutes or less, b) any posttraumatic amnesia lasting not more than 24 hours, c) any alteration of mental status at the time of the accident (e.g., feeling dazed, disoriented, or confused), and d) any focal neurologic deficits, which may or may not be transient, resulting in loss of consciousness or posttraumatic amnesia no more severe than described in a) and b) and, after 30 minutes, an initial Glasgow Coma Scale10 score of 13 to 15. Potential subjects were asked to undergo an in-person diagnostic interview using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS).11 Patients were between 18 and 60 years old, met DSM-III-R criteria for major depression on the DIS, and had a minimum score of 18 on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D).12

Exclusion criteria included severe language or cognitive deficits that would compromise their ability to comprehend or answer verbal or written questions; current serious medical illness; pregnancy or breast-feeding; mass brain lesions; history of more than one TBI; current or past psychosis or mania; current alcohol or drug abuse; current psychoactive medication use; prior use of sertraline; or current suicidal ideation requiring hospitalization. On the basis of these criteria, 32 advertisement respondents were excluded from participation. The four most common reasons for exclusion were history of more than one TBI (n=8), more than 24 months since TBI (n=7), prior use of sertraline (n=5), and severity of TBI (n=4).

All study participants gave written informed consent, as determined by the University of Washington's institutional review board. All subjects were administered the depression, dysthymia, panic, generalized anxiety, and alcohol and substance abuse and dependence sections of the DIS. DSM-III-R symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder were also assessed during the interview. All patients completed baseline questionnaires, which included the Symptom Checklist-90–Revised (SCL-90-R),13 the Brief Anger and Aggression Questionnaire,14 the Medical Outcomes Study Health Status Questionnaire–Short Form (SF-36),15 the Sickness Impact Profile,16 the Head Injury Symptom Checklist (HISC),17 and the Sheehan Disability Scale18 modified for patients with head injuries.

Subjects were informed that they would receive placebo for a week at some time during the trial as well as 8 weeks of treatment with sertraline. All subjects received one capsule of an inert placebo every morning during the first week of the trial. If the Ham-D decreased by 50% or dropped below 10, the patient would be judged a placebo responder but would complete the active treatment portion of the study. Patients were then given an 8-week single-blind course of sertraline, which started at 25 mg every morning. After 1 week, the dose was adjusted in the range of 25–50 mg per day, depending on tolerability. Further adjustment was made in week 3 in the range of 25–100 mg/day, and during weeks 4 through 8 the dose was adjusted in the range of 25–200 mg/day, depending on clinical response and tolerability. Medication side effects were noted at each assessment point. The Ham-D and Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI)19 were administered at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8. At week 8, all baseline questionnaires were readministered.

Treatment response was determined by a 50% drop on the 17-item Ham-D from baseline to week 8. A remission was determined by a final Ham-D of 7 or less. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare Ham-D scores over time. Baseline and endpoint psychological and disability measures were compared by use of paired t-tests. Two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables were used to compare remitters to nonremitters on baseline data. All t-tests were two-tailed. McNemar's test was used to compare categorical data on postconcussive symptom status on the HISC. For this analysis, the categories of symptoms that were worsening or staying the same were combined and compared with the category of symptoms that were improving in a 2×2 table of concordant and discordant pairs. Means are reported with standard deviations throughout.

RESULTS

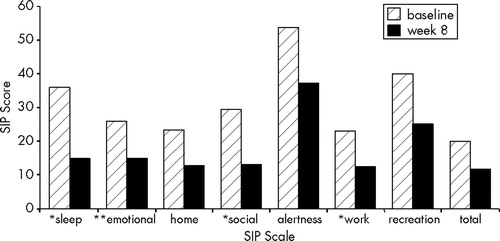

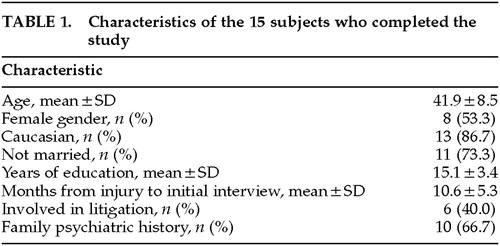

Sixteen patients began the study and 15 completed the protocol. The demographics of the patients who completed the study are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients who completed the study was 41.9 years (range 24–54). Thirteen (86.7%) were Caucasian. The mean time from TBI to initial interview was 10.6 months (range 5–24). Six (40%) were currently in some form of litigation. The patient who dropped out of the study complained of headache, dizziness, nausea, tinnitus, and lethargy after 1 day of sertraline 25 mg. Table 2 shows the rates of current and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses among the 15 patients who completed the study.

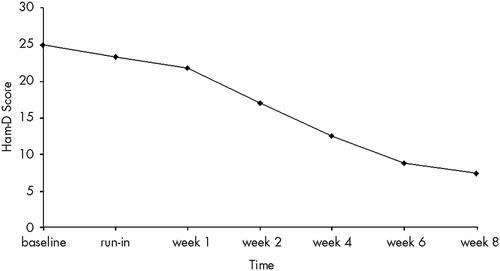

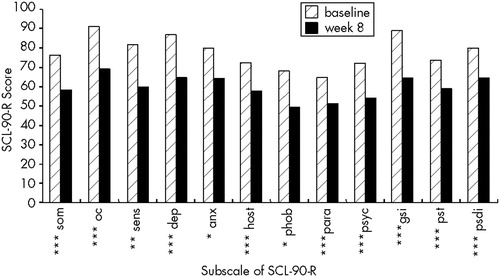

The mean Ham-D score at baseline assessment was 25±4.4 (range 18–32) among those who completed the study; the score was 24 for the patient who dropped out. None of the patients had a 50% drop in Ham-D after the 1-week, single-blind, placebo run-in period, and baseline scores were not significantly different from scores after 1 week of placebo. The mean Ham-D score at the end of the 8-week treatment phase was 7.2±5.3 (range 1–22;), representing a mean drop of 71.2%. Thirteen patients (86.7%) had a 50% drop in Ham-D (“response”), and 10 (66.7%) had a final Ham-D score of 7 or less (“remission”). Mean scores are displayed in Figure 1. No significant differences emerged between remitters and nonremitters on any of the demographic or diagnostic variables listed in Tables 1 and 2. The post-treatment mean was significantly less than both the baseline mean (t=10.44, df=14, P<0.001), and the post-placebo run-in mean (t=11.14, df=14, P<0.001). A significant time effect on Ham-D scores was found in the repeated-measures ANOVA (F=73.2; df=1,14; P<0.001). There was no confounding by age, gender, or education. Significant drops were seen in the CGI severity, efficacy, and improvement subscales from the end of placebo run-in to the end of treatment, with respective scores of 4.6 , 4.3, and 3.9 after placebo run-in and 1.9, 1.9, and 1.7 post-treatment (P<0.001 for all pairs). Thirteen (86.7%) had a CGI improvement score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) at week 8. Standardized T-scores on all SCL-90-R scales were reduced significantly from baseline to week 8 (Figure 2).

The final dose of sertraline ranged from 25 mg to 150 mg (mean=75±39.0 mg). Remitters had a mean final dose of 57.5±23.7 mg, and nonremitters had a final dose of 110±41.8 mg. Adverse effects that occurred in 3 or more patients were nausea (n=4), abdominal cramps (n=4), headache (n=3), and diarrhea (n=3).

Scores on the Brief Anger and Aggression Questionnaire dropped significantly (t=2.33, df=14, P<0.05) from a mean of 9.3±4.1 at baseline to 6.5±5.1 post-treatment.

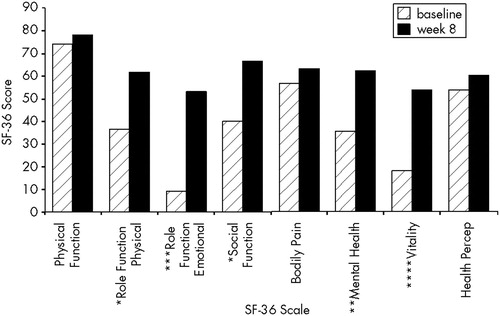

Significant improvement was seen in the SF-36 subscales of physical role functioning (t=2.3, df=14, P<0.05), emotional role functioning (t=4.4, df=14, P<0.005), social functioning (t=2.7, df=14, P<0.05), mental health (t=3.3, df=14, P<0.01), and vitality (t=5.9, df=14, P<0.001). Results are displayed in Figure 3. Comparison scores in general, medical, depressed, and TBI populations have been reported elsewhere.3,20,21

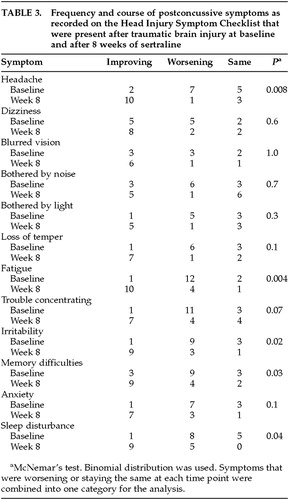

Patients showed significant improvements on the Sickness Impact Profile subscales of sleep and rest (t=2.9, df=14, P<0.05), emotional behavior (t=3.8, df=14, P<0.005), social interaction (t=2.4, df=14, P<0.05), and work (t=2.3, df=11, P<0.05). Results are displayed in Figure 4. The subscales of ambulation, body care and movement, and mobility were excluded because baseline scores were less than 10. Comparison scores in general, medical, and TBI populations have been reported elsewhere.16,17,22,23

Scores on the Sheehan Disability Scale also improved significantly from baseline to post-treatment in all 3 subscales of family functioning (5.5±3.1 to 3.2±3.7; t=3.0, df=14, P<0.05), social functioning (5.3±2.8 to 3.5±3.5; t=2.6, df=14, P<0.05), and work functioning (5.6±2.8 to 3.8±3.5; t=2.5, df=14, P<0.05).

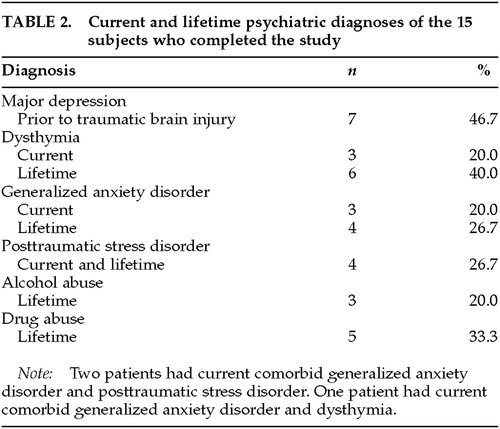

Patients rated postconcussive symptoms that were present after their TBI on the Head Injury Symptom Checklist at baseline and post-treatment. Symptoms were rated as being the same, worsening, or improving. The number of patients who reported improving symptoms increased from baseline to week 8 for all 12 postconcussive symptoms (Table 3). There were significantly more patients reporting improvement from baseline to post-treatment in the symptoms of headache, fatigue, irritability, memory difficulties, and sleep disturbance. Patients also rated the severity of their injury before treatment, on average, as 4.7±2.1 on a 0 to 10 Likert scale, which is significantly more severe than their post-treatment mean rating of 3.4±2.5 (t=3.0, df=14, P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

This pilot study suggests that sertraline may be efficacious in treating major depression in patients who have sustained a mild traumatic brain injury within the past 2 years. Two-thirds of patients had remission of their depression. Our findings are consistent with Cassidy's case series,4 in which 5 of 9 patients with severe TBI and major depression were found to be “moderately” or “markedly” improved with the serotonergic antidepressant fluoxetine. Reports of the efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants have been inconsistent.5–8 The inconsistent results found in these latter studies may be due to the small sample sizes, the wide range of case definitions for both TBI and depression, the inconsistent diagnostic methods used, and the lack of controlling for confounding variables. No large-scale, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of antidepressants for depression have been performed in the TBI population.

The doses required in this study are similar to those needed in the general population for the treatment of major depression without psychotic features. In general, side effects were minimal.

All subscales on the SCL-90-R decreased significantly, suggesting that treating depression decreases overall psychological distress across many domains. Because patients with TBI typically do not present with symptoms that fall into strict DSM diagnostic categories, but rather with an array of symptoms that may include depression, anxiety, irritability, anger, and even psychotic symptoms, this finding is encouraging.

Our finding that sertraline is associated with decreased depressive symptoms after TBI is consistent with evidence about the neuropathological mechanism that may contribute to the development of major depression following TBI. Human postmortem pathologic,24 cerebrospinal fluid,25 and imaging26 evidence supports a role for serotonin in the depressions of neurologic patients. Patients who are depressed following mild TBI have blunted prolactin response to buspirone, suggesting altered serotonin function in these patients compared with patients not depressed after mild TBI.27

Behavioral problems, particularly agitation and aggression, are often comorbid with depression28 and can occur in up to 70% of patients with TBI.29 Although it is well known that anger and aggression are common problems among patients with TBI, they are typically associated with and recognized in patients with more severe injuries. Our finding that patients reported their levels of anger and aggression as significantly improved after treatment for depression may show that anger and aggression are more of a problem, and more treatable, among patients with mild TBI than previously recognized. Sertraline has been shown to improve aggression significantly in neuropsychiatric patients.30,31 Even among medically and psychiatrically healthy volunteers, the magnitudes of psychometric assaultiveness, irritability, negative affect, and behavioral affiliation were correlated to plasma levels of the SSRI paroxetine.32

The present study shows that treating major depression following TBI may significantly improve functioning in a variety of areas, including emotional functioning and mental health; physical functioning, sleep, and vitality; and social, work, and family functioning. Given the myriad stressors that can affect a patient's physical, social, work, and family functioning, the finding that pharmacological treatment of depression can improve functioning in these areas is especially salient.

This study also suggests that treating depression in patients with mild TBI may significantly decrease the burden of postconcussive symptoms. Postconcussive symptoms are a significant problem in many patients with mild TBI.33 Most patients see improvement in these symptoms within the first month, but many experience continuing symptoms for months or years after their injury. While some educational and behavioral treatments for postconcussive symptoms have been developed,34 no pharmacological trials have been performed and no treatments for postconcussive symptoms have been widely studied.

Although many postconcussive symptoms overlap with symptoms of depression, our current study shows a decrease in postconcussive symptoms that do not overlap with depression, such as headache, dizziness, and blurred vision, and a change in perception of head injury severity with treatment of depression. Studies in other medical populations have also shown decreased subjective severity of physical symptoms and level of illness and distress with antidepressants.35,36 Screening for and treating depression in patients with persisting postconcussive symptoms may be an effective way to decrease unnecessary suffering and reduce excess disability. Treating depression in mild TBI patients may also minimize health services utilization and costs by decreasing unexplained somatic symptoms, perception of illness severity and disability, and subsequent illness behavior.

Methodological limitations of this study must lead to caution in interpreting the results. This was a nonrandomized, single-blind study; therefore, some improvements over time may have been a result of natural improvement or regression to the mean in distressed patients that was independent of the intervention. The results cannot be generalized to all TBI populations because of the small sample size and the large proportion of Caucasian, female, and highly educated patients compared with the general TBI population in the United States. Because we do not have follow-up data beyond 8 weeks of treatment, it is not possible to conclude whether or not the positive effects of sertraline were maintained. However, all patients who had remission of their depression elected to continue sertraline.

Future research will require controlled, double-blind studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods to determine the efficacy and effectiveness of different antidepressants in treating depressive symptoms, in decreasing associated psychological, behavioral, cognitive, and somatic symptoms, and in decreasing functional disability.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Joan Russo, Ph.D., for statistical assistance. This study was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals. The work was presented in part at the 152nd annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, May 15–20, 1999.

FIGURE 1. Mean scores on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D) among the 15 subjects who completed the studyThe 8-week mean was significantly lower than the baseline mean (P<0.001) and the post-placebo run-in mean (P<0.001)

FIGURE 2. Standardized T-scores on the Symptom Checklist-90–R (SCL-90-R) at baseline and after 8 weeks of sertralineSom=somatization; oc=obsessive-compulsiveness; sens=interpersonal sensitivity; dep=depression; anx=anxiety; host=hostility; phob=phobic anxiety; para=paranoia; psyc=psychoticism; gsi=general symptom index; pst=positive symptom total; psdi=positive symptom distress index. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005.

FIGURE 3. Scores on the SF-36 Health Status Questionnaire at baseline and after 8 weeks of sertraline*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005; ****P<0.001.

FIGURE 4. Scores on the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) at baseline and after 8 weeks of sertraline*P<0.05; **P<0.005.

|

|

|

1 Rosenthal M, Christensen BK, Ross TP: Depression following traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79:90–103Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Busch CR, Alpern HP: Depression after mild traumatic brain injury: a review of the current research. Neuropsychology Review 1998; 8:95–108Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Fann JR, Katon WJ, Uomoto JM, et al: Psychiatric disorders and functional disability in outpatients with traumatic brain injuries. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1493–1499Google Scholar

4 Cassidy JW: Fluoxetine: a new serotonergically active antidepressant. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1989; 4:67–69Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Varney NR, Martzke JS, Roberts RJ: Major depression in patients with closed head injury. Neuropsychology 1987; 1:7–9Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Wroblewski BA, Joseph AB, Cornblatt RR: Antidepressant pharmacotherapy and the treatment of depression in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a controlled, prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:582–587Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Saran AS: Depression after minor closed head injury: role of dexamethasone suppression test and antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 1985; 46:335–338Medline, Google Scholar

8 Dinan TG, Mobayed M: Treatment resistance of depression after head injury: a preliminary study of amitriptyline response. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:292–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Kay T, Harrington DE: Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1993; 8:86–87Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Teasdale G, Jennett B: Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. Lancet 1974; 2:81–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Robins LN, Helzer JE, Weissman MM, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:381–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1980; 23:56–62Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Derogatis LR, Lipman R, Rickels K, et al: The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a measure of primary symptom dimensions, in Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology: Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry, edited by Pichot P. Basel, Switzerland, Karger, 1974Google Scholar

14 Maiuro RD, Vitalliano PP, Cahn TS: A brief measure for the assessment of anger and aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 1987; 2:166–178Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). Med Care 1992; 30:473–483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, et al: The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care 1981; 19:787–805Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 McLean A, Dikmen S, Temkin N, et al: Psychosocial functioning at 1 month after injury. Neurosurgery 1984; 14:393–399Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Shear MK, Klosko J, Fyer MR: Assessment of anxiety disorders, in Measuring Mental Illness: Psychometric Assessment for Clinicians, edited by Wetzler S. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1989Google Scholar

19 Guy W: ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology, revised. DHEW Publ No (ADM)76–338. Rockville, MD, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976Google Scholar

20 Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al: Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262:907–913Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262:914–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Bergner M, Bobbit RA, Pollard WE, et al: The Sickness Impact Profile: validation of a health status measure. Med Care 1976;14:57–67Google Scholar

23 Dikmen S, Machamer J, Temkin N: Psychosocial outcome in patients with moderate to severe head injury:2-year follow-up. Brain Inj 1993; 7:113–124Google Scholar

24 Chen CPL-H, Alder JT, Bowen DM, et al: Presynaptic serotonergic markers in community-acquired cases of Alzheimer's disease: correlations with depression and neuroleptic medication. J Neurochem 1996; 66:1592–1598Google Scholar

25 Mayeux R, Stern Y, Sano M, et al: The relationship of serotonin to depression in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 1988; 3:237–244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Mayberg HS: Frontal lobe dysfunction in secondary depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:428–442Link, Google Scholar

27 Mobayed M, Dinan T: Buspirone/prolactin response in post head injury depression. J Affect Disord 1990; 19:237–241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Swanson JW, Holzer CE, Ganju VK, et al: Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:761–770Medline, Google Scholar

29 MacKinlay WW, Brooks DN, Bond MR, et al: The short-term outcome of severe blunt head injury as reported by the relatives of the injured person. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1981; 44:527–533Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Hellings JA, Kelley LA, Gabrielli WF, et al: Sertraline response in adults with mental retardation and autistic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:333–336Medline, Google Scholar

31 Ranen NG, Lipsey J, Treisman G, et al: Sertraline in the treatment of severe aggressiveness in Huntington's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:338–340Link, Google Scholar

32 Knutson B, Wolkowitz OM, Cole SW, et al: Selective alteration of personality and social behavior by serotonergic intervention. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:373–379Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Brown SJ, Fann JR, Grant I: Postconcussional disorder: time to acknowledge a common source of neurobehavioral morbidity. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:15–22Link, Google Scholar

34 Mittenberg W, Tremont G, Zielinski RE, et al: Cognitive-behavioral prevention of postconcussion syndrome. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 1996; 11:139–145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Sullivan M, Katon W, Russo J, et al: A randomized trial of nortriptyline for severe chronic tinnitus. Effects on depression disability and tinnitus symptoms. Arch Intern Med 1993; 153:2251–2259Google Scholar

36 Borson S, McDonald GJ, Gayle T, et al: Improvement in mood, physical symptoms, and function with nortriptyline for depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Psychosomatics 1992; 33:190–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar