Vascular Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease: Is There a Difference?

Abstract

This study examined differences between vascular dementia (VaD) by the NINDS/AIRENS criteria and Alzheimer's disease (AD) on clinical grounds. A consecutive series of 517 patients with probable and possible VaD or AD were evaluated for cognitive, functional, and behavioral symptoms and separated into three subgroups by duration of dementia. These AD and VaD subgroups were then compared on a series of standardized clinical measures. The only consistent trends were for VaD patients to be more depressed, more functionally impaired, and less cognitively impaired within each disease duration subgroup. The authors conclude that there are few differences between clinically diagnosed VaD and AD. Subclassification of VaD into subgroups will improve the clinical utility of this nosologic entity.

Dementia is a relatively common condition, affecting 5% to 8% of the population over age 65.1 It is a growing economic problem because of the aging of the population, and there is a need to tackle it aggressively. One way to do this is by early identification and treatment, which depends on correct diagnosis. Dementia is a rather broad syndrome of global cognitive decline without clouding of consciousness. It has as many as 60 to 70 different known causes,2 some reversible, some not.3 Not all causes can be identified prior to autopsy. Current nosology proposes that the two most common causes are Alzheimer's disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD), with respective frequencies of 70% and 15% of all dementias.4 There is a need to distinguish between these two types of dementia while patients are still alive because of the differences in treatment, prognosis, and management.

Alzheimer's disease, which used to be a diagnosis of exclusion, can be diagnosed with certainty at autopsy. It can also be diagnosed with reliable clinical criteria established in 1984.5,6 The National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders (NINCDS/ADRDA) criteria specify that AD cannot be diagnosed if any other form of dementia is present.5,6 AD seems to behave as a nosological entity. It has a predictable pattern of cognitive impairment,7 whose severity is correlated with selective neuronal death proceeding in an orderly pathologic spread from the hippocampus and subcortical nuclei, with selected neurotransmitter deficiencies, to temporoparietal and then frontal regions, and then to global involvement.6,8 Cognition declines at a predictable rate of about 4 Mini-Mental State Examination points per year,7,9 and there is limited variance around this slope.7 Death is also predictable at an average of 9 years from disease onset7 and is related to cognitive decline.10 Motor function is less affected by the disease, as the motor cortex is spared initially.8,11 Functional decline is at first a consequence of cognitive decline,12 stemming from inattentiveness, amnesia, apraxia, aphasia, and agnosia, and also from “negative symptoms” such as social withdrawal, apathy,13 or depression.14,15 At end stage the patient becomes immobile, partly because of pathological invasion of the motor cortex.11

AD has a wide range of associated mental and behavioral problems, including aggression, depression, delusions, hallucinations, apathy, and others.15–18 These result in part from neurotransmitter imbalances such as acetylcholine deficiency,6 norepinephrine excess19,20 and deficiency,21 and frontal lobe dopamine receptor insensitivity.22 These disturbances are common,23 and they frequently are the cause for institutionalization24 and consequent increase in economic burden.25 The diagnosis of AD on clinical grounds is usually confirmed by autopsy results.26

Vascular dementia (VaD), on the other hand, is more problematic as a nosologic entity. While the criteria for AD have remained stable for 16 years, multiple criteria for VaD have been proposed in this same period.27–31 The Hachinski Ischemic Scale, still used today, related such elements as abrupt onset of dementia, stepwise deterioration, fluctuating course, history of strokes, and depression to multi-infarct dementia, which correlated with decreased blood flow.26 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), 3rd edition, revised,30 established Multi-Infarct Dementia on the basis of history and physical examination incorporating the above elements and adding distribution of deficits as an early discriminating sign. The DSM 4th edition,31 renaming this as Vascular Dementia, acknowledged that the course is quite variable and not always stepwise, dropped the requirement of patchy distribution of deficits, and allowed evidence to be either laboratorial or physical. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/Asociation Internationale pour la Recherche et l'Enseignment en Neurosciences (NINDS/AIRENS) criteria29 required both physical and imaging evidence of cerebrovascular disease instead of one or the other and did not include stepwise progression as a requirement, acknowledging a multiplicity of possible courses. VaD seems to be a distinct form of dementia, although some have questioned whether it is an entity at all because of its heterogeneity.32 Commonly cited risk factors in favor of a VaD diagnosis are stroke, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, congestive failure, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, alcohol abuse, and arteriosclerosis.3,33–35 Cognitive impairment in VaD cases is directly correlated with blood pressure, age, and cardiovascular complications, and inversely correlated with education.12 The dementia is presumed to be caused by tissue injury from ischemia, with diverse pathologic patterns ranging from complete cortical death to mild subcortical hypoperfusion.9,36 This tissue injury can be partly reversible, irreversible with cell death, or slowly progressive through spreading oxidative damage.37,38

VaD has many different possible courses. Different authors have defined from four to eight different VaD subtypes, each with a distinct course.8,39–42 Subtypes are defined by stroke type and the presence of periventricular white matter lesions on MRI, which may be an independent cause of cognitive decline.43,44 However, VaD continues to be considered as a single category. When it is so considered, the rate of cognitive decline for VaD is similar to that for AD,8 and the life expectancy of VaD is 5 years, shorter than that of AD.45 The neuropsychological characteristics of the clinically diagnosed VaD, such as impairments in syntax, verbal comprehension, visuospatial ability, or primary and semantic memory, are very similar to those seen in AD.46 Although symptoms in VaD have been analyzed largely from the point of view of stroke location, blood flow, and frontal involvement,47–53 the differences from AD in cognitive, functional, and behavioral symptoms are not striking.46,54–56

Most important, in VaD the pathological diagnosis usually does not confirm the clinical diagnosis. Dementia that is clinically diagnosed as VaD is often diagnosed at autopsy as AD or mixed AD and VaD,57–60 leading some to wonder if pure VaD really exists.32,37,60,61 Treatment consists mostly of prevention of further strokes, control of hypertension, treatment of arteriosclerosis,3,35,62 and trials of rehabilitation.3 Because the diagnosis of VaD often comes too late for any effective recuperative treatment,32 the attitude of physicians toward treatment often tends to be nihilistic.2

There is no gold standard for the clinical distinction between AD and VaD. Indeed, there are many similarities in the clinical presentations of the two disorders. Although there may be greater motor impairment in VaD,9,52 differences in psychomotor speed between the two disorders are debatable.46,63 The primary etiologic element in VaD is ischemia, but the subsequent dementia progression involves a neurodegenerative process very similar to that seen in AD.38,60,64,65 Many of the risk factors for VaD are also risk factors for AD.66,67 The apolipoprotein E E4 allele, which is a risk factor for AD, is also associated with VaD.68–70 There are treatments such as propentofylline that may work in both AD and VaD.71 Neuropsychological testing at best can differentiate VaD from AD only 77% of the time.72 Overlap of the two on autopsy is seen in 30% to 75% of cases.8,58,60

Given this question of whether VaD can be distinguished from AD on clinical grounds, new and reliable73 criteria were recently proposed (NINDS/AIRENS).29 These criteria required both physical and imaging evidence of cerebrovascular disease instead of one or the other. We could find only two published comparisons of AD and VaD using these new criteria, both from our group. Payne et al.14 found that depression was worse in early VaD and in late AD, but these differences depended on functional impairment. Klein et al.74 found that wandering was more frequent in AD and was correlated with cognitive decline in AD but not VaD. Reports of sensitivity for the clinical diagnosis with the new VaD criteria when compared with the findings at autopsy have varied from 20%75 to 60%,76 with a specificity of 26%60 to 80%.76

Duration is a confounding factor that needs to be taken into account in studies of vascular dementia because of the unpredictability of the course of VaD. In AD cognitive decline has a predictable relationship to duration, but in VaD to look at symptoms by severity of cognitive impairment (such as by MMSE score) is actually to look at them at various disparate points in their natural history. A sudden early massive cortical or thalamic stroke may be accompanied by sudden severe dementia, whereas subcortical arteriosclerosis may have a course that is slow and progressive and mimics AD. Duration of dementia is a better measure than severity of dementia for determining VaD stage, and duration may still serve as an indicator for cognitive decline in AD.

In this study our intent was to test the hypothesis that VaD using the AIRENS criteria differs substantially from AD on clinical grounds across different durations of illness. We used a large clinical sample to maximize the size of individual duration groups. Duration of illness was ascertained by careful assessment of cognitive symptoms in interviews of patients and knowledgeable informants such as family members and primary care physicians. We compared cognitive, functional, and mental or behavioral symptoms at short, intermediate, and long durations of AD and VaD.

METHODS

Participants

A total of 1,114 patients were evaluated for dementia at the Johns Hopkins Neuropsychiatry and Memory Group (NMG) between September 1994 and October 1998. They were seen at one of two clinic sites: the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, MD (65%), or Copper Ridge in Sykesville, MD (35%). From this sample we excluded all patients who did not have a recorded duration of illness (n=135) because duration could not be assessed accurately. From the remaining 979 patients we then selected those with a clinical diagnosis (NINCDS/ADRDA) of possible AD (n=78) or probable AD (n=333) and combined them into one group (n=411). We also selected those with a clinical diagnosis (NINDS/AIRENS) of probable or possible VaD (n=106), leading to a total of 517 patients in the study. Patients excluded from this selection of dementia types had either “mixed” dementia, traumatic brain injury, depression, developmental disability, mental retardation, Down's syndrome, or another diagnosis. Data on these patients were collected and compiled anonymously as part of routine clinical care and were exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

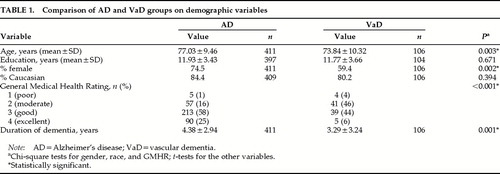

Table 1 shows the demographic makeup and clinical characteristics of the AD and VaD groups. Combining the two groups, the mean age of the entire study sample was 76.4 years (SD=9.7); 71.4% were women, and 83.5% were Caucasian. Eighty-seven percent of the sample were currently married or widowed, and only 5% had never been married. Approximately 91% were living in their own or a family member's home; the rest resided in assisted-living settings. Sixty-seven percent had their general health rated as fair or good on the General Medical Health Rating.77

Assessment

Each patient underwent an extensive neuropsychiatric examination as previously described.14,17,74 A comprehensive history, neurological examination, and mental status examination were performed by experienced geriatric psychiatrists. This assessment included complete evaluation of any cognitive symptoms, using input from the patient's family members and referring physicians. Brain imaging (MRI or CT) and laboratory assessments (including chemistries, electrolytes, complete blood count, liver tests, thyroid tests, serum B12, serum folate, sedimentation rate, rapid plasma reagin for syphilis, urinalysis, ECG, and chest X-ray) were performed (or reviewed in cases where they had been ordered by referring physicians). Diagnoses were made by using the information obtained above, along with information from family members, other caregivers, and primary care physicians, to ensure reliability.78 Patients were also rated on the following standardized scales:

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).79 This is a cognitive test designed to assess orientation to place and time, memory, attention, concentration, language, and visuospatial skills. Although the MMSE was originally designed to test mental status, decreased scores are associated with dementia.79

Psychogeriatric Dependency Rating Scale80 with three subscales, the 10-item orientation subscale (PGDRS-Orientation), the 15-item behavioral subscale (PGDRS-Behavior), and the 12-item physical dependency subscale (PGDRS-ADL). The orientation subscale was used as a continuous measure of cognition, the behavioral subscale was used as a continuous global measure of behavioral disturbance, and the ADL subscale was used as a continuous measure of impaired performance of activities of daily living (ADL).

Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD).81 This observer-rated scale was designed to measure depressive symptoms in dementia. It has high reliability and validity for standardized psychiatric diagnosis.81,82 Nineteen depressive symptoms were rated for their presence in the past week on a scale of 0 to 2, with 0 standing for absent, 1 for mild or intermittently present, and 2 for severe or frequently present. Additionally, patients with a CSDD score greater than 12 were defined as having “moderate to severe” depression because scores greater than 12 on the CSDD in patients with dementia are strongly correlated with a psychiatric diagnosis of a major depressive episode.82,83

Additional data collected at evaluation included an assessment for the frequency of occurrence, within the 2 weeks prior to admission, of the following: falls, accidents, delusions, hallucinations, depression, crying spells, sleep disorder, apathy, catastrophic reactions, aggression, and wandering. These behaviors were recorded as occurring never, occasionally, or frequently. “Any occurrence” of one of these symptoms was assessed as well as “frequent” occurrence as defined above.

We were interested in differences between clinically diagnosed VaD and AD patients in the following domains: cognition, function, and behavior. To measure cognition, we used the MMSE and the PGDRS-Orientation subscale rating. To measure functional decline, we used the occurrence or nonoccurrence of falls and accidents, as well as the PGDRS-ADL subscale rating. To measure behavior, we used the occurrence or nonoccurrence, and the frequent occurrence or nonoccurrence, of delusions, hallucinations, depression, crying spells, sleep disorder, apathy, catastrophic reactions, aggression, and wandering, as described above, as well as the PGDRS-Behavior subscale rating.

Analyses

All analyses were performed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 8.1 for Windows. The sample was divided into the following subgroups, each containing about one-third of the sample: 1) duration of disease for not more than 2 years, 2) duration between 2 and 5 years, and 3) duration greater than 5 years.

Variables were used with missing data. The frequency of missing data for the General Health Rating was 12%; for the CSDD, 21.5%; for the MMSE, 7.7%; and for the PGDRS, 25%. For all other variables, 1% to 4% of data were missing. Different cases had different pieces of missing data. Had we excluded all cases with missing data, our sample would have been 30% to 40% smaller.

Means and significant differences in means on t-tests were estimated for the two dementia groups for all continuous variables, such as PGDRS scales, CSDD, and MMSE, by duration group and across all durations. The numbers and percentages of discrete variables, such as falls, accidents, and behavioral symptoms, were cross-tabulated for significance on chi-square tests by each duration group and overall.

RESULTS

As can be seen in Table 1, the VaD and AD groups were not significantly different for race or education, but they did differ for gender, age, and overall duration of dementia. General medical health was significantly better in AD. There was also a difference in average duration of dementia on evaluation. This result was one of the reasons we divided durations into thirds to study the frequency and severity of symptoms.

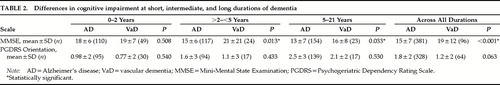

Table 2 compares patients with VaD and AD on the MMSE and PGDRS-O scales. The results show significantly higher mean MMSE scores for VaD patients with intermediate and long durations of dementia and for VaD patients across all durations. There were no significant differences in mean MMSE scores with short durations, or in PGDRS orientation scores at any duration. Thus, in longer durations, AD patients had relatively more severe global cognitive impairment.

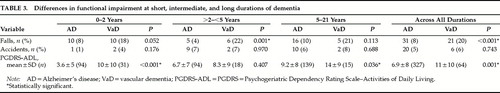

Table 3 compares the two groups on functional impairment at short, intermediate, or long durations and across all durations. On the PGDRS-ADL, patients with VaD at short and long durations and overall were more impaired. They were also more likely to fall at intermediate durations and across all durations. However, there were no significant differences in the occurrence of accidents at any duration category. The greater proportion of ADL impairment in VaD may reflect a larger percentage of patients with motor strokes or gait impairment, conditions that can occur earlier in VaD than in AD.

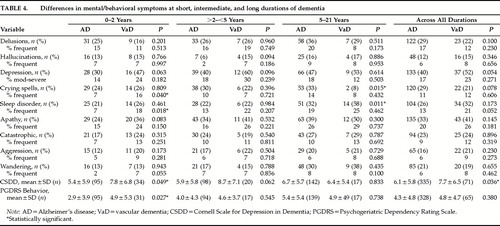

Table 4 compares the two groups on mental/behavioral disturbances at short, intermediate, and long durations. At early durations (0–2 years), patients with VaD were more likely to have frequent crying spells and frequent sleep disorders, had more overall depressive symptoms (CSDD), and had more severe behavior disorders (PGDRS-B). At intermediate durations (2–5 years), there were no significant differences in any symptoms. At long durations (5–21 years), patients with AD were more likely to have crying spells and sleep disorders. Across all durations, patients with VaD were more likely to have overall depressive symptoms (CSDD).

It is difficult to assess whether these results show any meaningful differences between AD and VaD. Out of 112 comparisons, there were 15 significant differences. With a significance level of 0.05, we would expect 6 positive results by chance alone. In Table 4 there were 7 significant differences found in a total of 80 comparisons made. Four positive results would have happened by chance alone. In cognitive impairment, the results show a slower rate of decline in VaD on one scale but not on another. VaD shows more functional impairment than AD in 3 out of 4 duration categories of one scale, emphasizing short and long durations, whereas falls are significantly increased in 2 out of 4 categories, emphasizing intermediate durations, and there are no significant differences in accidents at all. In mental/behavioral disturbances, VaD shows more depression in short durations and overall, but not in intermediate and long durations. VaD shows greater behavioral disturbances only at early durations. Whenever significant differences occurred between VaD and AD in specific symptoms (n=4 out of 72 comparisons) there was a noncorrespondence in the degree of severity of the symptom. When occurrence of frequent crying spells was significantly different, overall occurrence of crying spells was not, and vice versa. When frequent sleep disorder was significantly different, overall sleep disorder was not, and vice versa. The inconsistencies in these patterns of significant differences between VaD and AD, coupled with the relatively few differences, call attention to the difficulty of making a clinical distinction between VaD and AD.

In an effort to classify our sample using different methods, we first used MMSE scores, dividing our sample into thirds by score. Once again, there were no significant differences between behaviors in VaD and AD, other than the differences already noted. The durations were also divided into quartiles, and again the resulting pattern and number of significant differences between VaD and AD in duration categories was similar to that shown in Tables 2, 3, and 4. We tried separating possible from probable AD and comparing each to VaD, but the results here too were comparable to those shown in Tables 2, 3, and 4. We compared Alzheimer's dementia and vascular dementia using males only and females only, and by persons over and under the median age for each group, and the results were no different from those obtained initially. We estimated the power of our study to detect differences between scores in VaD and Ad. in the closes comparisons, the study had 83%–87% power to detect statistically significant differences, assuming alpha=0.05.

DISCUSSION

Our study goal was to conduct a detailed clinical comparison between patients diagnosed with VaD by the NINDS/AIRENS criteria and patients with AD, using a large sample size, both overall and by different duration intervals. There have been many attempts in the past to diagnose VaD on clinical grounds,55 including the Hachinski Ischemic Scale, which incorporated “depression” and “relatively retained personality” as distinguishing elements for VaD.84 We found in comparing the clinical aspects of VaD and AD that the only consistent trends were for VaD patients to be more depressed, more functionally impaired, and less cognitively impaired. These trends were not clear-cut. For example, the MMSE showed relatively less cognitive decline in VaD at different disease durations, but the PGDRS Orientation scale did not. Although the PGDRS-ADL score showed greater functional impairment in VaD, and although VaD patients had more falls, the number of other accidents they had was not significantly different. The CSDD showed VaD patients had more depression early, but depression later was comparable in frequency, and the frequency of depression at the initial interview was not significantly different at any duration.

Differences found in mental/behavioral disorders occurred at disparate duration intervals and were unconfirmed by related variables. There is a suggestion that behaviors in AD may grow worse with duration of disease, but the pattern in VaD is unclear. In addition, we suspect that the differences in cognition, which were inconsistent between related variables, were influenced by selection bias. The study may have excluded stroke victims who became moderately or severely demented, who died, who were placed in nursing homes, or who were otherwise unable to ever arrive at an outpatient clinic to participate in the study. Although these things can happen with AD, many cases of AD are not accompanied by sudden and severe medical illnesses such as stroke.

We could find no longitudinal studies of VaD, or any comparing its symptoms with those of AD by disease duration. Nor could we find any studies of the course of VaD subgroups to see if they differed from AD. There have been two cross-sectional comparisons of multiple behavioral symptoms in VaD and AD using other diagnostic criteria and looking at symptom frequency across all durations. One study of 28 matched pairs showed behavioral differences, with the VaD patients having more severe behavioral retardation, depression, and anxiety than AD patients at comparable levels of cognitive impairment.85 Another study of 126 demented patients showed that although behavioral symptoms increased with cognitive impairment there were no significant differences between VaD, AD, and mixed dementia.86 Others have found that depression is worse in VaD;87 that depression is worse in AD;88 that psychosis is worse in AD;89 or that psychosis does not differ between dementia types.85

This study raises three questions: Is VaD different from AD? Does VaD behave as a nosological entity apart from AD? And are there subgroups of VaD that could be identified by clinical manifestations or course that are different from AD?

Our study suggests that if there is an entity different from AD called VaD, one that needs to be treated differently from AD, then we need more precise criteria in order to define the entity. The study also reinforces one argument already identified by others, especially given the autopsy overlap between the two disorders, that VaD is not a single nosologic entity. One construct of VaD might include a subset of AD patients with strokes; a subset of patients with strokes but no AD; a subset of patients with leukoaraiosis,90 no strokes, and no AD; and a subset of AD patients with leukoaraiosis but no strokes. The stroke groups might be further subdivided into large-vessel strokes and small-vessel strokes. In the stroke groups, the infarcts appear to worsen the severity of functional impairment by adding motor disturbances and thus causing functional impairments disproportionate to the degree of cognitive decline. In addition, the strokes increase the likelihood of depression—most likely because certain strategic strokes, such as left-sided frontal or basal ganglia strokes, can cause depression.91 Finally, VaD might be subdivided into subgroups based on the presumed cause of the cerebrovascular disease, such as hypertension or diabetes. Unfortunately, we did not collect sufficient data in this study to subdivide our VaD group further. However, we propose that future studies of VaD collect these data and investigate the clinical features of subgroups of the broad VaD category.

In the AD-plus-infarcts subgroup of VaD, the relationship between AD and the infarcts is unclear. Does the dementia that develops from infarction continue to be driven by the same pathogenic mechanisms, or does it lead to the initiation of AD if the patient indeed does not already have AD? In the subgroup of VaD patients with leukoaraiosis but no strokes and no AD, the patients might follow the course of Binswanger's dementia or that of lacunar states. In the last subgroup, it has been shown that AD compromised by leukoaraiosis has a more behaviorally severe course than AD with no leukoaraiosis.92,93 Finally, there exists support for vascular cognitive impairment without AD or VaD or stroke, but frequently with leukoaraiosis—long supported by Dr. Hachinski.94

If VaD is a distinct nosologic entity, how can we identify it reliably? The literature on VaD has largely evaded what may be the problem. By concentrating on tissue damage and the few behavioral symptoms that are predictable because of subcortical involvement, studies may have failed to see that the unpredictability of the symptoms of VaD is indicative of its diagnostic uncertainty. The category may be too large to be meaningful.32 Imagine combining all neurodegenerative dementias such as Huntington's, Parkinson's, Pick's, and so forth and then trying to decide on the clinical characteristics and treatment, or combining all the dementias of infectious origin, such as AIDS, Lyme, meningitis, and others32 and then trying to map the rates of cognitive decline, functional impairment, behavioral impairment, and length of life. How predictive would these overall rates be for any one of the constituents? If we wish to continue to consider VaD as a separate entity or collection of entities, we need to define its subgroups and to measure the various courses of VaD in terms of mortality, cognition, functional decline, and behavior disturbances, and also predict risk factors and clinical characteristics of those who will follow these different clinical courses. And those studies should go to autopsy in order to validate the clinical criteria.

The data here show some differences in the comparison of AD to VaD, suggesting that VaD may be a different clinical entity, whether or not the autopsy pathology is entirely distinct. However, our data support the idea that better clinical criteria are needed for VaD to help us reliably distinguish it from AD. The clinical criteria we have only provide us with an averaging of symptoms. Perhaps its differentiation of VaD from AD is difficult80 because VaD is a cluster of unrelated causes of vascular brain damage,54,86 and were it carved up into reliable subsets maybe we could recognize the subsets more readily than the single category we now have.39 Then perhaps we could chart its courses, determine its etiologies and overlaps, predict its behaviors, and find even more specific treatments. More immediately, we may need to rely more insistently on MRI, SPECT, or PET blood flow studies95,96 and other diagnostic tests.97–99

Limitations of this study include the sample selection, the use of the clinical diagnosis, missing data, and differences in age and gender between the groups. From what we know of MMSE scores in AD,7 it would seem that in our group early durations were underestimated and later durations were overestimated by AD patients and their informants. It may be a tendency for AD patients and their families to underestimate the duration of illness more than VaD patients do, since the onset of AD is insidious and the onset of VaD is often heralded by a stroke and memorable hospitalization. The limitation of sample selection is that frequently these patients were seen by psychiatrists for behavioral problems and thus they might not represent the population seen, for example, by a stroke clinic or in a nursing home.

Another confounder is the use of cross-sectional comparison. Because the course of AD is typically predictable, this type of analysis should be a first approximation of natural history or course. However, in VaD, where there are many distinct possible courses, cross-sectional analysis eliminates the severe cases that never came to the study, thus overstating the cognitive and functional levels of the average VaD patient. For the most part it artifactually produces rates for surviving VaD patients at any duration of illness who have not yet been permanently institutionalized. Although duration is a measure of cognitive and functional decline in AD, the unpredictable nature of VaD precludes this correlation. If subsets of VaD could be isolated, such as all the patients who died within the first two years of admission, or those with Binswanger's disease, which has a more gradual and predictable course, then the cross-sectional approach of symptoms by duration would be a more accurate reflection of disease course. With methods such as this or the employment of longitudinal studies with subgroups, the identification of VaD might become easier and the treatment more specific.

|

|

|

|

1 Terry RD, Katzman R, Bick KL (eds): Alzheimer's Disease. New York, Raven, 1993Google Scholar

2 Geldmacher DS, Whitehouse PJ Jr: Differential diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1997; 48(suppl 6):S2–S9Google Scholar

3 Konno S, Meyer JS, Terayama Y, et al: Classification, diagnosis and treatment of vascular dementia. Drugs Aging 1991; 11:361–371Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Whitehouse PJ, Sciulli CG, Mason RM: Dementia drug development: use of information systems to harmonize global drug development. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997; 33:129–133Medline, Google Scholar

5 McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–949Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Cummings JL, Vinters HV, Cole GM, et al: Alzheimer's disease: etiologies, pathophysiology, cognitive reserve, and treatment opportunities. Neurology 1998; 51(suppl 1):S2–S17Google Scholar

7 Olichney JM, Galasko D, Salmon DP, et al: Cognitive decline is faster in Lewy body variant than in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1998; 51:351–357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Chui HC: Dementia: a review emphasizing clinicopathologic correlation and brain-behavior relationships. Arch Neurol 1989; 46:806–814Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Ballard C, Patel A, Oyebode F, et al: Cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia and senile dementia of Lewy body type. Age Ageing 1996; 25:209–213Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Evans DA, Smith LA, Scherr PA, et al: Risk of death from Alzheimer's disease in a community population of older persons. Am J Epidemiol 1991; 134:403–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Geula C: Abnormalities of neural circuitry in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1998; 51:S18–S29Google Scholar

12 Forette F, Seux ML, Thijs L, et al: Detection of cerebral ageing, an absolute need: predictive value of cognitive status. Eur Neurol 1998; 39(suppl 1):2–6Google Scholar

13 Reichman WE, Coyne AC, Amirneni S, et al: Negative symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:424–426Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Payne JL, Lyketsos CG, Steele C, et al: Relationship of cognitive and functional impairment to depressive features in Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:440–447Link, Google Scholar

15 Fitz AG, Teri L: Depression, cognition, and functional ability in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42:186–191Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Wragg RE, Jeste DV: Overview of depression and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:577–587Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Lyketsos CG, Steele C, Galik E: Physical aggression in dementia patients and its relationship to depression. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:66–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Marin RS, Firinciogullari MS, Biedryzycki RC: Group differences in the relationship between apathy and depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 1994; 182:235–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Elrod R, Peskind ER, DiGiacomo L, et al: Effects of Alzheimer's disease severity on cerebrospinal fluid norepinephrine concentration. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:25–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Russo-Neustadt A, Cotman CW: Adrenergic receptors in Alzheimer's disease brain: selective increases in the cerebella of aggressive patients. J Neurosci 1997; 17:5573–5580Google Scholar

21 Forstl H, Burns A, Luthert P: Clinical and neuropathological correlates of depression in Alzheimer's disease. Psychol Med 1992; 22:877–884Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 DeKeyser J, Ebinger G, Vauquelin G: D1-Dopamine receptor abnormality in frontal cortex points to a functional alteration of cortical cell membranes in Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol 1990; 47:761–763Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Teri L, Borson S, Kiyak A, et al: Behavioral disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, and functional skill: prevalence and relationship in Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1989; 37:109–116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Steele C, Rovner B, Chase GA, et al: Psychiatric symptoms and nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1049–1051Google Scholar

25 Ernst RL, Hay JW, Fenn C, et al: Cognitive function and the costs of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1997; 54:687–693Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Joachim CL, Morris JH, Selkoe DJ: Clinically diagnosed Alzheimer disease: autopsy results in 150 cases. Ann Neurol 1988; 24:50–56Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Ott BR, Grace J: Vascular dementia. Med Health R I 1997; 80:150–154Medline, Google Scholar

28 World Health Organization: International Statistical Classification of Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10). Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992Google Scholar

29 Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al: Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies, report of the NINDS/AIREN International workshop. Neurology 1993; 43:250–259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

31 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994 Google Scholar

32 Hachinski V: Vascular dementia: a radical redefinition. Dementia 1994; 5:130–132Medline, Google Scholar

33 Perry E, Kay DW: Some developments in brain ageing and dementia. Br J Biomed Sci 1997; 54:201–215Medline, Google Scholar

34 Lis CG, Gaviria M: Vascular dementia, hypertension, and the brain. Neurol Res 1997; 19:471–480Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Lechner H: Status of treatment of vascular dementia. Neuroepidemiology 1998; 17:10–13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 Sultzer DL, Levin HS, Mahler ME, et al: A comparison of psychiatric symptoms in vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1806–1812Google Scholar

37 Golelik PB, Nyenhuis DL, Garron DC, et al: Is vascular dementia really Alzheimer's disease or mixed dementia? Neuroepidemiology 1996; 15:286–290Google Scholar

38 Nogawa S, Zhang F, Ross ME, et al: Cyclo-oxygenase-2 gene expression in neurons contributes to ischemic brain damage. J Neuroscience 1997; 17:2746–2755Google Scholar

39 Wallin A: Subtype identification in vascular dementia: an important step towards more precise diagnosis and improved treatment. Lakartidningen 1995; 92:3217–3219Google Scholar

40 Babikan V, Ropper AH: Binswanger's disease: a review. Stroke 1987; 18:2–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Ortiz JS, Knight PV: Review: Binswanger's disease, leukoaraiosis and dementia. Age Ageing 1994; 23:75–81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 Loeb C, Meyer JS: Vascular dementia: still a debatable entity? J Neurol Sciences 1996; 143:31–40Google Scholar

43 van Gijn J: Leukoaraiosis and vascular dementia. Neurology 1998; 51(suppl 3):S3–S8Google Scholar

44 Junque C, Pujol J, Vendrell P, et al: Leuko-araiosis on magnetic resonance imaging and speed of mental processing. Arch Neurol 1990; 47:151–156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 Hebert R, Brayne C: Epidemiology of vascular dementia. Neuroepidemiology 1995; 14:240–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 Almkvist O: Neuropsychological deficits in vascular dementia in relation to Alzheimer's disease: reviewing evidence for functional similarity or divergence. Dementia 1994; 5:203–209Medline, Google Scholar

47 Starkstein SE, Sabe L, Vazquez S, et al: Neuropsychological, psychiatric, and cerebral blood flow findings in vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Stroke 1996; 27:408–414Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al: Clinically defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:562–565Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 Binetti G, Padovani A, Magni E, et al: Delusions and dementia: clinical and CT correlates. Acta Neurol Scand 1995; 91:271–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50 Ishii N, Nishihara Y, Imamura T: Why do frontal lobe symptoms predominate in vascular dementia with lacunes? Neurology 1986; 36:340–345Google Scholar

51 Robinson RG, Kubos KL, Starr LB, et al: Mood disorders in stroke patients. Brain 1984; 107:81–93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 Schorer CE: Alzheimer and Kraepelin describe Binswanger's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 4:55–58Link, Google Scholar

53 Padovani A, Di Piero V, Bragoni M, et al: Patterns of neuropsychological impairment in mild dementia: a comparison between Alzheimer's disease and multi-infarct dementia. Acta Neurol Scand 1995; 92:433–442Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 Bucht G, Adolfsson R, Winblad B: Dementia of the Alzheimer type and multi-infarct dementia: a clinical description and diagnostic problems. J Am Geriatr Soc 1984; 32:491–497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55 Verhey FRJ, Ponds RWHM, Rozendaal N, et al: Depression, insight, and personality changes in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1995; 8:23–27Medline, Google Scholar

56 Vreeling FW, Houx PJ, Jolles J, et al: Primitive reflexes in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1995; 8:111–117Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57 Olichney JM, Hansen LA, Hoffstetter R, et al: Cerebral infarction in Alzheimer's disease is associated with severe amyloid angiopathy and hypertension. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:702–708Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58 Victoroff J, Mack WJ, Lyness SA, et al: Multicenter clinicopathological correlation in dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1476–1484Google Scholar

59 Kukull WA, Larson EB, Reifler TH, et al: The validity of 3 clinical diagnostic criteria for AD. J Neurol 1990; 40:1364–1369Google Scholar

60 Nolan KA, Lino MM, Seligmann AW, et al: Absence of vascular dementia in an autopsy series from a dementia clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46:597–604Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61 Bendixen, B: Vascular dementia: a concept in flux. Current Opinion in Neurology and Neurosurgery 1993; 6:107–112Medline, Google Scholar

62 Black RS, Barclay LL, Nolan KA, et al: Pentoxifylline in cerebrovascular dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40:237–244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63 Almkvist O, Backman L, Basun H, et al: Patterns of neuropsychological performance in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Cortex 1993; 29:661–673Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64 Marcusson J, Rother M, Kittner B: A 12-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of propentofylline (HWA 285) in patients with dementia according to DSM III-R. Dementia Geriatr Cogn Disord 1997; 8:320–328Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65 Ihara Y, Hayabara T, Sasaki K, et al: Free radicals and superoxide dismutase in blood of patients with Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci 1997; 153:76–81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66 Skoog I: Status of risk factors for vascular dementia. Neuroepidemiology 1998; 17:2–9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67 Ott A, Stolk RP, Hofman A, et al: Association of diabetes mellitus and dementia: the Rotterdam Study. Diabetologia 1996; 39:1392–1397Google Scholar

68 Frisoni GB, Calabresi L, Geroldi C, et al: Apolipoprotein E e4 allele in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Dementia 1994; 5:240–242Medline, Google Scholar

69 Igata-Yi R, Igata T, Ishizka K, et al: Apoprotein E genotype and psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:906–908Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70 Ramachandran G, Marder K, Tang M, et al: A preliminary study of apolipoprotein E genotype and psychiatric manifestations of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1996; 47:256–259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71 Wimo A, Witthaus E, Rother M, et al: Economic impact of introducing propentofylline for the treatment of dementia in Sweden. Clin Ther 1998; 20:552–566Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72 Barr A, Benedict R, Tune L, et al: Neuropsychological differentiation of Alzheimer's disease from vascular dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1992; 7:621–627Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Lopez OL, Larumbe MR, Becker JT, et al: Reliability of NINDS-AIREN clinical criteria for the diagnosis of vascular dementia. Neurology 1994; 44:1240–1245Google Scholar

74 Klein DA, Steinberg M, Galik E, et al: Wandering behavior in community residing persons with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999; 14:272–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75 Wetterling T, Kanitz R-D, Borgis K-J: Comparison of different diagnostic criteria for vascular dementia (ADDTC,DSM-IV,NINDS-AIREN). Stroke 1996; 27:30–36Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76 Gold G, Giannakopoulos P, Montes-Paixao C, et al: Sensitivity and specificity of newly proposed clinical criteria for possible vascular dementia. Neurology 1997; 49:690–694Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77 Lyketsos CG, Galik E, Steel C, et al: The “General Medical Health Rating” (GMHR): a bedside global rating of medical comorbidity in patients with dementia. J Am Geriatr Society 1999; 47:487–491Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78 Teri L, Wagner A: Assessment of depression in patients with Alzheimer's disease: concordance among informants. Psychol Aging 1991; 6:280–285 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, Hughes PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

80 Wilkinson IM, Graham-White J: PGDRS: a method of assessment for use by nurses. Br J Psychiatry 1980; 137:558–565Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81 Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, et al: Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. Biol Psychiatry 1988; 23:271–284Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

82 Pearlson GD, Ross CA, Lohr WD, et al: Association between family history of affective disorder and the depressive syndrome of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:452–456Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83 Lyketsos CG, Tune L, Pearlson G, et al: Major depression in Alzheimer's disease: an interaction between gender and family history. Psychosomatics 1996; 37:380–384Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

84 Hachinski VC, Potter P, Mersku H: Multi-infarct dementia: a cause of mental deterioration in the elderly. Lancet 1974; ii:207–210Google Scholar

85 Sultzer DL, Levin HS, Mahler ME, et al: A comparison of psychiatric symptoms in vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1806–1812Google Scholar

86 Swearer JM, Drachman DA, O'Donnell BF, et al: Troublesome and disruptive behaviors in dementia: relationships to diagnosis and disease severity. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988; 36:784–790Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87 Ballard C, Bannister C, Solis M, et al: The prevalence, associations, and symptoms of depression amongst dementia sufferers. J Affect Disord 1996; 36:135–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

88 Berrios CE, Bakshi N: Manic and depressive symptoms in the elderly: their relationships to treatment outcome, cognition, and motor symptoms. Psychopathology 1991; 24:31–38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

89 Ballard C, Bannister C, Graham C, et al: Associations of psychotic symptoms in dementia sufferers. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 67:537–540Crossref, Google Scholar

90 Hachinski VC, Potter P, Merskey H, et al: Leuko-araiosis. Arch Neurol 1987; 44:21–23Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

91 Lyketsos CG, Treisman GJ, Lipsey JR, et al: Does stroke cause depression? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:103–107Google Scholar

92 Lopez OL, Becker JT, Reynolds CF, et al: Psychiatric correlates of MR deep white matter lesions in probable Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 9:246–250Link, Google Scholar

93 Ortiz JS, Knight PV: Review: Binswanger's disease, leukoaraiosis and dementia. Age Ageing 1994; 23:75–81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

94 Bowler JV, Hachinski V: Vascular cognitive impairment: a new approach to vascular dementia. Baillere's Clinical Neurology 1995; 4:357–377Google Scholar

95 Ries F, Horn R, Hillekamp J, et al: Differentiation of multi-infarct and Alzheimer dementia by intercranial hemodynamic parameters. Stroke 1993; 24:228–235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

96 Mielke R, Kessler J, Szelies B: Vascular dementia: perfusional and metabolic disturbances and effects of therapy. J Neural Transm 1996; 16 (suppl 47):183–191Google Scholar

97 Hansson G, Alafuzoff I, Winblad B, et al: Intact brain serotonin system in vascular dementia. Dementia 1996; 7:196–200Medline, Google Scholar

98 Blin J, Baron JC, Dubois B, et al: Loss of brain 5-HT2 receptors in Alzheimer's disease: in vivo assessment with positron emission tomography and [18F]setoperone. Brain 1993; 116(pt 3):497–510Google Scholar

99 Mecocci P, Cherubini A, Bregnocchi M, et al: Tau protein in cerebrospinal fluid: a new diagnostic and prognostic marker in Alzheimer disease? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1998; 12:211–214Google Scholar