Cognitive Deficits in Patients With Hepatic Cirrhosis and in Liver Transplant Recipients

Abstract

This study assessed cognitive deficit in patients diagnosed with different stages of hepatic cirrhosis and in liver transplant recipients. A short protocol consisting of several psychometric tests was used. Cirrhotic patients showed a degree of mental impairment in all the functions studied. The severity of the deficit was related to the degree of hepatic dysfunction. In contrast, liver transplant recipients presented only a slightly altered cerebral dysfunction in comparison to the control group. Their cognitive capacity was slightly better than that of patients with asymptomatic cirrhosis.

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a clinical picture that can present when there is damage to the brain and nervous system as a complication of liver disorders. It is characterized by various neurologic symptoms, including changes in reflexes, consciousness, and behavior that can range from mild to severe.1–3 HE has not been attributed to any one toxic substance or altered mechanism, but is considered to result from the combined effect of several factors.1,3,4

Hepatic encephalopathy can manifest in different stages or episodes (I, II, III, IV). However, before the first episode, or between episodes, cerebral function can be altered in a subclinical or latent manner.5–7 Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy (SHE) is very frequent in patients with hepatic cirrhosis. In a sample of 165 cirrhotic patients, Das et al.8 found that 62.4% had SHE. In SHE, patients appear to have a normal mental state, but they present subclinical cognitive alterations that can make it impossible for them to perform normal day-to-day tasks9,10 that require correct cerebral function, such as driving, operating machinery, and other work-related activities.5,6,11–14 Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy is therefore an important social problem. Moreover, in Western society hepatic cirrhosis is one of the 10 most common causes of death.15 Between 51% and 70% of cirrhotic patients present cognitive alterations, although the social and health implications of this have so far been ignored.16,17

At present, medical research is coming up with new treatments for liver failure, and orthoptic liver transplantation (OLT) is frequently used in the more severe cases.18,19 However, some authors have shown that cognitive function does not completely recover after transplantation.20,21

In the present study, cognitive deficits associated with hepatic cirrhosis were assessed by applying short tests that are easy to interpret. By this, we aimed to demonstrate that neuropsychological tests are a valid instrument to assess the mental capacities of patients with hepatic cirrhosis and liver transplant recipients.

METHODS

Subjects

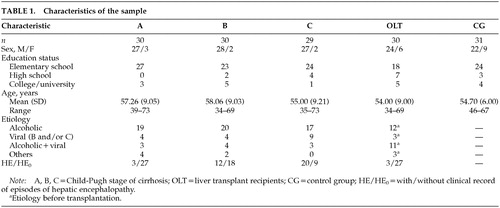

A total of 150 subjects were studied (128 men and 22 women, mean age 56.2±9.2 years). Of these, 89 were diagnosed with hepatic cirrhosis and were subdivided into groups according to their Child-Pugh stage of cirrhosis22: 30 patients in Child-A, 30 in Child-B, and 29 in Child-C. Cirrhosis was diagnosed by using classical clinical and analytical criteria and was confirmed by liver biopsy when this was permitted by coagulation parameters (as occurred in 70% of cases). The fourth group comprised 30 patients who had received liver transplants for previous cirrhosis (OLT). The control group (CG) comprised 31 healthy volunteer blood donors. Regular analytical tests carried out on these individuals ruled out the possibility of any hepatic condition. The age, educational level, and gender ratio in the CG group were similar to those of the cirrhotic and transplanted groups. The demographic, clinical, educational, and epidemiological characteristics of the participants are given in Table 1.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Tests were selected by applying three criteria: capability to assess deficits associated with HE (attention deficit, memory loss, disorientation, impaired ability to reason, and concrete thinking); simplicity and ease of interpretation; and brevity, taking less than 30 minutes, in total, to carry out. Following these criteria, we chose the Digit Span Forward and Digit Span Backward tests (DF, DB) of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale to assess patients' memory and immediate attention/recall.23 The rates of visual-motor processing and mental flexibility were assessed by the two parts of the Trail Making Test, A and B (TMT-A, B).24,25 General reasoning and nonverbal intelligence were assessed with the Raven's Progressive Matrices Test (RT).26 Only 13 of the illustrations from the RT were used, in increasing order of difficulty (4 belonging to scale A, 4 to scale B, 3 to scale C, and 2 to scale D). The design of the RT is such that each scale requires a strategic change to resolve the problem. Therefore, by selecting the first few illustrations of each scale we ensured that this difficulty factor did not disappear, and in this way sampled the conceptual capacities of the patients.

Procedure

Data from the neuropsychological examination were collected from patients attending the outpatient clinic of the Digestive System Unit of the Hospital Central de Asturias between September 1999 and December 2000. Patients diagnosed with HE had a clinical record of previous episodes of HE but did not present clinical signs of HE during their cognitive assessment. Patients classified as HE0 had no clinical or family history of any episode of HE. The OLT group was randomly selected from all the patients in post-transplantation follow-up in our hospital. The mean duration of the period from transplantation to the neuropsychological assessment was around 1.8 years (range 9–36 months). All subjects participating in the study provided their signed consent.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by using the statistical software package SPSS for Windows, version 8.5. The differences in cognitive variables between the different groups in the sample were determined by multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), followed by a univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a posteriori comparison between the different groups done by using Scheffé's test. Differences between the groups were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

RESULTS

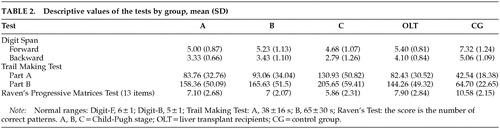

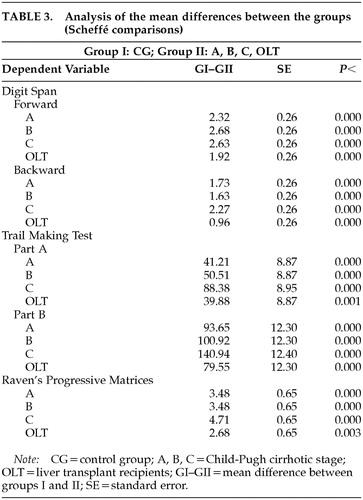

The results obtained from the scores of the five study groups on the five tests carried out are detailed in Table 2. Because the Wilks' lambda value (converted to F value) was F=72.81 (df=72,87, P=0.00), ANOVAs were carried out individually for each dependent variable. Differences in the performance of the patient groups on the tests in comparison to the control group are recorded in Table 3. No statistically significant differences in test scores were found between etiologies or between genders.

On the Digit Span tests, significant differences were found between the four experimental groups and the control group (DF subtest: A, B, C, OLT vs. GC, F= 873.68, df=5, 145, P=0.000; DB subtest: A, B, C, OLT vs. GC, F=429.60, df=5, 145, P=0.000). Significant differences were also found between the transplant recipients and the cirrhotic patients with Child-Pugh stage C on the DB test (C vs. OLT). On the TMT, there were significant differences between the four experimental groups and the control group (part A: F=204.32, df=5, 145, P=0.000; part B: A, B, C, OLT vs. GC, F=308.28, df=5, 145, P=0.000). On parts A and B, the Child-C group had significantly worse results than the other patient groups (C vs. A, B, OLT). On the RT, there were also significant differences between the four patient groups and the control group (A, B, C, OLT vs. GC, F=285.63, df=5, 145, P=0.000).

DISCUSSION

The neuropsychological tests that we administered confirmed the existence of cognitive impairment in patients with hepatic cirrhosis, and the deficit found was greater with increasing liver damage. Liver transplant recipients showed some degree of alteration in cerebral function in comparison to the control population, although they had better results than the group of cirrhotic patients.

On the Digits Forward and Digits Backward tests, subjects with OLT achieved higher direct scores than the groups with cirrhosis. On the DB test, the OLT group achieved scores within the normal range, reflecting a recovery of short-term memory. The DB test is clearly associated with functions of the temporal lobe and left frontal lobe,27 and low scores on this test are characteristic of patients with dementia. On the DF test, the values obtained by subjects with OLT were within the normal range but toward the lower end, implying some improvement in attention capacity, which according to some authors is the main cognitive parameter impaired in cirrhotic subjects.10 This improved performance in digit span tests had already been described by Oppong et al.28 in patients assessed pre and post liver transplantation. In relation to the groups with hepatic cirrhosis, direct scores of Child-A and Child-B groups on DF were at the lower end of the normal range but were significantly different from the CG. However, the greatest deficit was reflected in the DB test results, suggesting alterations in short-term memory that could not be attributed to differences in age or educational level with the control group.27 Results of the Child-C group showed that these subjects presented moderate dementia with auditory attention deficit and reduced short-term retention capacity.

On the other hand, the results of the TMT-A and B once again confirm that this is the most sensitive test to assess HE.16,24 Its visual and motor components have been shown to be correlated with alterations in psychomotor and visuopractic processes found in cirrhotic subjects that can be inferred from changes occurring in the basal ganglia.29 All experimental groups, cirrhotic patients and transplant recipients, presented some degree of mental deficit on TMT when compared with the healthy population. Here it should be borne in mind that only 30% of patients had previously suffered one or more episodes of HE, whereas 70% had never had any clinical manifestations of HE. Since the TMT correlates well with other tests of mental capacity and is very sensitive to brain damage,30 the scores obtained by the different groups confirmed the existence of cognitive deficits. As with the Digit Span tests, there was also a clear correlation between Child-Pugh stage of cirrhosis and the scores obtained on the TMT. Thus, patients with Child-C had the worst cognitive deficit compared with the other groups. In this test, the OLT patient group showed significant differences compared with the control group on both part A and part B. Other authors have observed differences between OLT patients and control subjects on part A, but not on part B. This could be due to the lower age of their OLT patients compared with those used in our study21,31 or to the range of time post transplant. This lack of recovery in OLT subjects could confirm the viewpoint of Tarter et al.32 They maintain that HE is a neuropsychiatric illness which, in addition to metabolic dysfunctions, is also characterized by changes in cerebral morphology that would explain why OLT patients do not make a full recovery. On the other hand, both parts of the TMT are highly correlated with lesions of the caudate nucleus, again confirming the existence of alterations in the basal ganglia in HE subjects. The TMT is also highly sensitive to educational level and age, but no differences in test performance could be attributed to these variables because they were similar in all our groups. It is also worth noting the large differences between the times taken to carry out parts A and B in the patient groups, reflecting the difficulty that all patient groups had in interpreting complex conceptual clues.27

The results obtained by the different Child groups using the 13 illustrations of the RT showed an impairment in concrete thinking, which is a good reflection of conceptual functions. Low results on this test would reflect the inability to form concepts using categories, generalizations, or general rules. The selection of illustrations from different scales enables assessment of both visuoperceptive skills, which are clearly associated with the right hemisphere (scale A), and analogical reasoning capacity with a verbal component, which is associated with the left hemisphere (scales B and above). The Child-C group showed severely impaired conceptual capacity by making mistakes on more than 50% of the illustrations, permitting a clear association to be established between the severity of hepatic disease and the RT results. It was interesting that patients with OLT had better results on this test than patients with liver cirrhosis. However, as has already been reported by other authors, the results reflected some degree of impairment in the OLT group compared with the control group.31,33

On the other hand, because chronic alcohol consumption was the etiology of cirrhosis in 63% of the patients in our series, some of the mental alterations observed in our tests could have been due to this habit. Miller and Saucedo34 have shown that alcoholics had lower scores on the RT, and Walton and Bowden35 have established a correlation between the number of years of alcohol consumption and digit test results. However, our analysis of the etiology of the cirrhosis did not reveal significant differences between cirrhosis of alcoholic origin and the other etiologies, suggesting that hepatic dysfunction constitutes the main origin of the observed mental alterations. In relation to this, Gilberstadt et al.36 found that alcoholics with cirrhosis obtained worse results in some tests than alcoholics without hepatic damage. Geissler et al.37 also concluded that the morphological changes of cirrhotic patients are related to the degree of hepatic dysfunction and not to long-term alcohol consumption.

Our work shows that neuropsychological tests are valid for assessing HE. However, they are not unanimously accepted for reaching a cognitive diagnosis. For this purpose, some authors consider neurological imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance, which can detect a larger proportion of patients with subclinical hepatic encephalopathy than neuropsychological tests, to be more reliable.38,39 Detecting these alterations is of considerable interest and importance because of the impact they have on the daily lives of these subjects5 and because of the need to find therapeutic solutions to minimize these deficits.6 In the future, it will probably be necessary to standardize the scores obtained by cirrhotic patients with different degrees of HE. When this is accomplished, by carrying out a series of short tests (less than 1 hour in total duration), the clinician will then be able to identify the degree of cognitive dysfunction of the patient and take the necessary prophylactic or therapeutic measures.

|

|

|

1 Jones EA: Pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy. Clinics in Liver Disease 2000; 4:467-485Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Quero JC, Hartmann IJC, Meulstee J, et al: The diagnosis of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis using neuropsychological tests and automated electroencephalogram analysis. Hepatology 1996; 24:556-560Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Albrecht J, Jones AE: Hepatic encephalopathy: molecular mechanisms underlying the clinical syndrome. J Neurol Sci 1999; 170:138-146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Ferenci P, Püspök A, Steindl P: Current concepts in the pathophysiology of hepatic encephalopathy. Eur J Clin Invest 1992; 22:573-581Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Schomerus H, Hamster W, Blunck H, et al: Latent portasystemic encephalopathy, I: nature of cerebral functional defects and their effect on fitness to drive. Dig Dis Sci 1981; 26:622-630Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Gitlin N, Lewis DC, Hinkley L: The diagnosis and prevalence of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in apparently healthy, ambulant, non-shunted patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1986; 3:75-82Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Collis I, Lloyd G: Psychiatric aspects of liver disease. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 161:12-22Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Das A, Dhiman RK, Saraswat VA, et al: Prevalence and natural history of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 16:531-535Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 McCrea M, Cordoba J, Vessey G, et al: Neuropsychological characterization and detection of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:758-763Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Groeneweg M, Quero JC, De Brujin I, et al: Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy impairs daily functioning. Hepatology 1998; 28:45-49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Srivastava A, Mehta R, Rothke SP, et al: Fitness to drive in patients with cirrhosis and portal-systemic shunting: a pilot study evaluating driving performance. J Hepatol 1994; 21:1023-1028Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Lockwood AH, Murphy BW, Donnelly KZ, et al: Positron-emission tomographic localization of abnormalities of brain metabolism in patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology 1993; 18:1061-1068Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD: The application of magnetic resonance spectroscopy to the study of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol 1996; 25:988-998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Ross BD, Jacobson S, Villamil F, et al: Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy: proton MR spectroscopic abnormalities. Neuroradiology 1994; 193:457-463Google Scholar

15 Corrao G, Ferrari P, Zambon A, et al: Trends of liver cirrhosis mortality in Europe, 1990-1989: age-period cohort analysis and changing alcohol consumption. Int J Epidemiol 1997; 26:100-109Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Sood GK, Sarin SK, Mahaptra J, et al: Comparative efficacy of psychometric tests in detection of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in nonalcoholic cirrhotics: search for a rational approach. Am J Gastroenterol 1989; 84:156-159Medline, Google Scholar

17 Jalan R, Gooday R, O'Carroll RE, et al: A prospective evaluation of changes in neuropsychological and liver function tests following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt. J Hepatol 1995; 23:697-705Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Pageaux GP, Souche B, Perney P, et al: Results and cost of orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis. Transplant Proc 1993; 25:1135-1136Medline, Google Scholar

19 Williams JW, Vera S, Evans LS: Socioeconomic aspects of hepatic transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol 1987; 82:1115-1119Medline, Google Scholar

20 Commander M, Neuberger J, Dean C: Psychiatric and social consequences of liver transplantation. Transplantation 1992; 53:1038-1040Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Tarter RE, Switala J, Arria A, et al: Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy: comparison before and after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation 1990; 50:632-637Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Pugh RH, Murria-Lysh IM, Dawson JL, et al: Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding esophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973; 60: 646-649Google Scholar

23 Wechsler D: Escala de inteligencia de Wechsler para adultos. Madrid, TEA Ediciones, 1993Google Scholar

24 Conn HO: Trailmaking and number-connection tests in the assessment of mental state in portal systemic encephalopathy. Dig Dis 1977; 22:541-550Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Reitan RM: Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills 1958; 8:271-276Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Raven JC: Matrices progresivas. Madrid, MEPSA, 1982Google Scholar

27 Lezak MD: Neuropsychological Assessment, Third Edition. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

28 Oppong KNW, Al-Mardini H, Thick M, et al: Oral glutamine challenge in cirrhotics pre and post-liver transplantation: a psychometric and analyzed EEG study. Hepatology 1997; 26:870-876Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Taylor-Robinson SD, Oatridge A, Hajnal JV, et al: MR imaging of the basal ganglia in chronic liver disease: correlation of T1-weighted and magnetization transfer contrast measurements with liver dysfunction and neuropsychiatric status. Metab Brain Dis 1995; 10:175-187Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Spreen O, Benton AL: Comparative studies of some psychological tests for cerebral damage. J Nerv Ment Dis 1965; 140:323-333.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Riether AM, Smith SL, Lewison BJ, et al: Quality-of-life changes and psychiatric and neurocognitive outcome after heart and liver transplantation. Transplantation 1992; 54:444-450Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Tarter RE, Hays AL, Sandford SS, et al: Cerebral morphological abnormalities associated with non-alcoholic cirrhosis. Lancet 1986; 1:893-895Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Carson KL, Hunt CM: Medical problems occurring after orthotopic liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci 1997; 42:1666-1674Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Miller WR, Saucedo CF: Assessment of neuropsychological impairment and brain damage in problem drinkers, in Clinical Neuropsychology: Interface With Neurologic and Psychiatric Disorders, edited by Golden CJ, Moses JA, Coffman JA, et al. New York, Grune and Stratton, 1983, pp 141-171Google Scholar

35 Walton NH, Bowden SC: Does liver dysfunction explain neuropsychological status in recently detoxified alcohol-dependent clients? Alcohol Alcohol 1997; 32:287-295.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 Gilberstadt SJ, Gilberstadt H, Zieve L, et al: Psychomotor performance defects in cirrhotic patients without overt encephalopathy. Arch Intern Med 1980; 140:519-521Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Geissler A, Lock G, Fründ R, et al: Cerebral abnormalities in patients with cirrhosis detected by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging. Hepatology 1997; 25:48-54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Catafau AM, Kulisevsky J, Berna L, et al: Relationship between cerebral perfusion in frontal-limbic-basal ganglia circuits and neuropsychologic impairment in patients with subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. J Nucl Med 2000; 41:405-410Medline, Google Scholar

39 Yang SS, Wu CH, Chiang TR, et al: Somatosensory evoked potentials in subclinical portosystemic encephalopathy: a comparison with psychometric tests. Hepatology 1998; 27:357-361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar