The Overt Aggression Scale for Rating Aggression in Outpatient Youth With Autistic Disorder: Preliminary Findings

Abstract

Aggression is a common and costly problem in youth with developmental disabilities. Rating scales that accurately capture and measure subtypes of aggression phenomenology, frequency and severity are urgently needed, in both clinical practice and research. The authors studied the Overt Aggression Scale (OAS) in a preliminary sample of eight outpatients who participated in an ongoing placebo-controlled study of valproate for aggression in autism. Subjects’ OAS aggression scores showed significant correlation with the already validated retrospectively rated Aberrant Behavior Checklist Community Scale irritability subscale. Further study of the OAS in outpatients with aggression and developmental disabilities is warranted.

Aggression is a common and costly problem among youth with autism spectrum disorders and developmental disabilities. At the same time, it is difficult to accurately capture and measure varied behaviors such as hitting, kicking, biting, punching, scratching, throwing furniture, head-banging, and self-hitting. A study of inpatient children in a psychiatry unit found that nursing shift reports underreported aggression severity and frequency when compared with directly recorded measures.1 In outpatients, aggressive behaviors are usually absent during office visits. Clinical assessment frequently relies on parental reports of aggression and any episode antecedents, topography, duration, and frequency details they can recall. Data collection by teachers is vital but remains largely missing in child psychiatry assessments and lacks uniformity. Such issues diminish the accuracy of ratings that assess overall aggression severity or global improvement by using rating scales such as the Clinical Global Impressions Scale.2

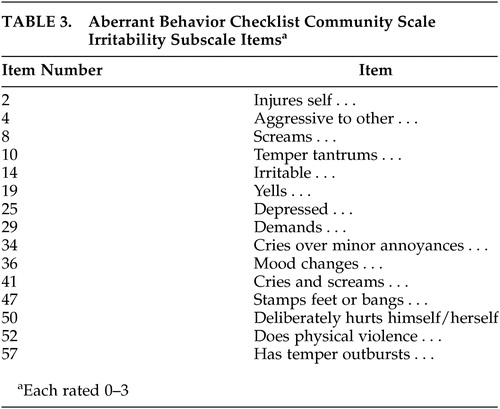

At the same time, most rating scales designed for persons with developmental disabilities do not directly capture and measure aggression. While the Aberrant Behavior Checklist Community Scale (ABC-C)3 is validated in this population, the parent or teacher must retrospectively average and record the severity of each problem behavior described in the 58 items of the scale. A subset of the items specifically rates aggression, principally the items in the Irritability Subscale. The same issues pertain to the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form.4 In such retrospective ratings, more recent problems and severe aggressions tend to overshadow periods of good behavior.

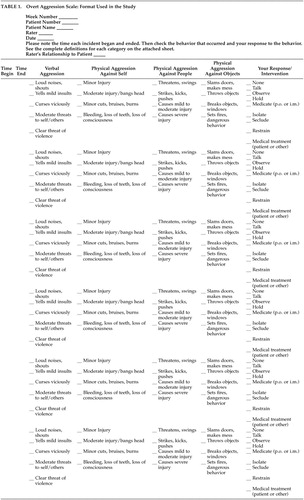

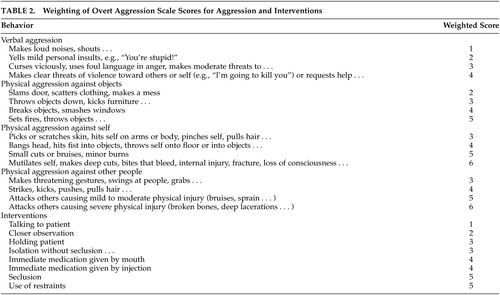

The Overt Aggression Scale (OAS)5 shows promise as an objective and prospective recording and rating instrument, although its use in persons with developmental disabilities requires validation. The OAS divides recording of aggressions into four subtypes, notably 1) verbal aggression, 2) physical aggression against others, 3) physical aggression against property or objects, and 4) physical aggression against self (self-injurious behavior) (Table 1). The starting and finishing times for each episode are recorded. Aggressions occurring less than 30 minutes apart are counted as part of the same episode. Specific aggression topography is checked in each category, varying from milder threatening forms of aggression, for example foot-stomping, yelling or slamming doors, to the most severe forms, resulting in injuries or unconsciousness. The most severe behavior in each category is then assigned a weighted score, as determined in the original OAS design (Table 2), and the weighted score in each of the four categories is added to give the OAS aggression score (e.g., 3+3+4+5=15). The intervention used to deal with the episode, varying from ignoring and verbal redirection, to isolating or physically holding the person, is also recorded, weighted, and added to the OAS aggression score to give the total aggression score (e.g., 3+3+4+5+3= 18). Outpatient studies involving subjects who are observed in different school and home settings do not include or rate the intervention employed, since the different interventional methods may vary by setting.

The OAS was originally validated in general adult inpatients with chronic neuropsychiatric illness accompanied by violent outbursts. Violent outbursts occur with significant variation in frequency in adult psychiatric inpatients on chronic wards6 over different weeks and by time of day. Preliminary studies using the OAS in inpatient children with conduct disorders show good promise. Kafantaris et al.1 found good user satisfaction, acceptable correlation with aggression items on the Children’s Psychiatric Rating Scale, and reflection of changes associated with drug treatment, in a study of child psychiatry inpatients. Studies of the OAS in outpatients and in persons with disabilities are still needed.

We employed OAS parent and teacher ratings of aggression performed on outpatient children and adolescents with autistic disorder as part of our ongoing study of aggression in autism. All subjects participated in this double-blind, parallel groups, placebo-controlled study of valproate efficacy and safety in the treatment of aggression. The preliminary OAS findings are compared with ratings made by the same observers on the ABC-C irritability subscale, filled out weekly on the same sample of subjects.

METHODS

Recordings of daily aggressions on the OAS, made at the time of each aggression, were obtained on eight outpatient children and adolescents (two female, six male) meeting autism disorder criteria on the Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised7 and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule.8 Subjects ranged in age from 7 to 19 years (mean=11.4). All subjects lived at home and attended school on weekdays. Seven subjects had severe mental retardation and one had unspecified mental retardation. In each case, informed consent was obtained from the parent or legal guardian after the study procedures were fully explained. At the time of study enrollment, the principal investigator (J.H.) and the study nurse (M.W.) discussed the method of OAS recording of each aggression with the parents and teachers, using examples of the type of episodes described for the subject in question. This included the time at the beginning and end of the episode, the type of aggression observed, and the response or intervention used. The study design comprises a week of placebo, followed by 8 weeks randomized to either active valproate or placebo. At each weekly study visit, the completed Parent and Teacher OAS and ABC-C forms were collected. The nurse and P.I. checked over the forms with the parent for completeness and clarified any recording questions raised. While it could be argued that this practice could affect subsequent data recorded, overall there were few issues to be clarified, and it is unlikely that a learning curve developed for raters that altered the apparent validity of the scales over the course of the study. In order to facilitate the entry of multiple episodes, we employed a modified format to allow for five episodes to be documented on a page. See Table 3 for details of the ABC-C irritability subscale questions. While weekly completion of the ABC-C irritability subscale is not the usual methodology for its use, this was an artifact of the larger study, which required weekly visits to monitor treatment response.

In the case of one severely hyperactive subject, with an extreme frequency of behavior problems, raters were instructed to rate only moderate and severe aggression, a problem which may lead to some sample bias. In one other case, of a subject sharing equal time in divorced parents’ homes, ratings of the parent judged to be more reliable were used. In the case of a subject with multiple different school teachers, ratings of the teacher reporting the most problems were used. While this method was chosen at the time, an alternative approach may be to average ratings across settings and then calculate interrater reliability.

After each study visit, the OAS and ABC-C irritability subscale recordings were rated, and then weekly OAS aggression scores were calculated and entered into the database, by the nonclinical data manager (E.J.N.). We attempted to minimize coaching of raters during the study, to reduce any possible bias associated with the method of not waiting until the end of the study to rate and enter data.

For eight subjects, each had 63 days of recordings, comprising 7 days of placebo lead-in and 8 weeks (56 days) in the randomized trial phase. There were nine parent OAS aggression scores for each child (one for the placebo week, plus nine for the weeks of drug or placebo), and five to nine teacher OAS aggression scores for each child. In order to justify the use of the OAS, we assessed the consistency between the results obtained by the OAS aggression scores and the results obtained by the validated ABC-C irritability scores. Consistency between the two scales was measured by the between-subject correlation of parent OAS aggression scores and parent ABC-C irritability scores and the between-subject correlation of the teacher OAS aggression scores and teacher ABC-C irritability scores. We also compared the internal consistency of the OAS aggression scores with the ABC-C irritability scores by comparing the within-subject correlation of parent and teacher OAS aggression scores with the within-subject correlation between parent and teacher ABC-C irritability scores. Pearson correlation coefficients were used in assessing statistical significance.

To measure the consistency between parent OAS aggression scores and parent ABC-C irritability scores, the OAS aggression scores and ABC-C irritability scores as recorded by the parent were each averaged over all time points to obtain overall average OAS aggression scores and ABC-C irritability scores. The correlation between these average scores was then computed, using a two-tailed Pearson r test. A similar procedure was performed to measure the consistency between teacher OAS aggression scores and teacher ABC-C irritability scores.

RESULTS

On the OAS, teachers rated a mean of 9.1 episodes per week (SD=8.9, range=0–34). Parents also rated a mean of 9.1 episodes (SD=6.6, range=0–29). The ranges of the averaged scores were as follows: for the teacher OAS aggression ratings, 0–216 (mean=56.0, SD=58.1); for the teacher ABC-C irritability scores, 0–44 (mean=16.7, SD=12.6); for the parent OAS aggression scores, 0–220 (mean=50.6, SD=43.8); and for the parent ABC-C irritability scores, 1–44 (mean=19.2, SD=11.0).

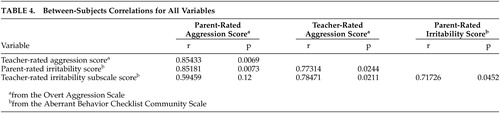

The between-subjects correlation of parent OAS aggression scores and parent ABC-C irritability scores was found to be 0.851 (p=0.007). Hence parent OAS aggression scores and parent ABC-C irritability scores are positively correlated. The between-subjects correlation of teacher OAS aggression scores and teacher ABC-C irritability scores was 0.78 (p=0.02) hence teacher OAS aggression scores and teacher ABC-C irritability scores are also positively correlated. These findings show that the OAS scale gives results consistent with the ABC-C irritability subscale scale (Table 4).

The between-subjects correlation of parent OAS aggression scores and teacher OAS aggression scores was 0.85 (p=0.007). The between-subjects correlation of parent ABC-C irritability subscale and teacher ABC-C irritability subscale was 0.72 (p=0.05). As measured by the between-subject correlation of parent and teacher scores, therefore, the OAS scale appears to be at least as consistent as the ABC-C irritability subscale scale. The within-subject correlation between parent and teacher OAS aggression scores was found to be 0.33 (p=0.01), compared to the within-subject correlation between parent and teacher ABC-C irritability scores, which was found to be 0.28 (p=0.04). Hence, as measured by the within-subject correlation between parent and teacher scores, the OAS scale appears to be at least as consistent as the ABC-C irritability subscale scale.

DISCUSSION

Our preliminary experience and statistical findings with the OAS suggest it is a promising instrument for use in outpatients and in children and adolescents with developmental disabilities, including mental retardation and autism. The mean of 9.1 episodes per week recorded by both parents and teachers on the OAS gives an idea of the overall aggressivity of this population. The range in number of episodes was also similar for teachers (0–34) and parents (0–29). The statistical findings showed that the OAS gives scores that are consistent with scores obtained from the validated ABC-C irritability subscale. This within-subject correlation between parent and teacher scores was significant but low, however we note that this was low for both the OAS and the ABC-C irritability subscale. The within-subject correlation may be low due to the influence of setting on behavior problems manifesting at school versus at home. The important point when looking at the within-subjects correlation is that the OAS appears to give results that are as internally consistent as the validated ABC-C irritability subscale. Thus it would be worthwhile to continue collection of data with this measure for our full study sample of 30 subjects. It is necessary to note also that since parents, teachers and the study investigators were expecting aggression improvement on study medication, a bias in the “improved” direction may exist in this study. Analysis of the OAS as a measure of drug response was not done on this small sample, which comprised some subjects on placebo and some treated with the study drug. This analysis will be done at the end of the completed study.

Some methodological issues that we encountered involving the ratings require clarification and further study. Parents and teachers were instructed to rate only moderate and severe aggressive behaviors in one subject with severe hyperactivity and extremely frequent behavior problems. In one case involving divorced parents spending equal time with the child, the ratings of the most high-functioning and reliable parent were used. In this case one parent denied observing the child having aggressive behavior problems, even when we observed aggression in that parent’s presence. Similarly, for subjects with multiple school teachers, the recordings of the teacher reporting the most problems were selected for rating. As mentioned, these are potential sources of bias, and require further study. Another, and possibly better approach may be not to judge parental functionality and reliability, but to ensure that all raters (be they divorced parents or various teachers) are able to read and effectively use the instrument as assessed through prestudy training. Another potential problem in comparing the OAS with the ABC-C irritability subscale is that not all items in the ABC-C irritability subscale (e.g., depressed or mood changes) reflect aggression in the same way as quantified by the OAS (Table 3). These items are in the minority, however.

The OAS can provide detailed, quantifiable data on aggressive and self-injurious behavior episodes, including duration of each episode as it occurs. It also provides descriptive detail of the behavioral topography of the episodes (and possibly in the future, dimensions or subtypes) as well as the severity of each episode. The parent and teacher also record the interventions required. Though it may at first appear complicated to the parent or teacher doing the ratings, initial introduction of the OAS by the principal investigator and study nurse as it may pertain to their child or student is helpful. Recording of the presence and type, or absence, of antecedents may prove valuable, as an additional column to the left-hand side of the scale. Some may argue against the inclusion of antecedents, however, in a future edition of the OAS, as this may be a subjective judgment rather than a reliable rating, although it may be a helpful guide in selecting a treatment approach.

Children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders also show great variability in the frequency of their outbursts across different settings such as school or home, and across time periods. High-stimulus noisy environments, illness, changes in routine, demands or transitions are common settings and antecedents for aggression.9 While some youths manifest problems predominantly at home, others become aggressive mainly at school. It is important when studying aggressive behavior problems, therefore, to obtain accurate recordings from school teachers, as well as home-based data, rather than word-of-mouth impressions. In the most severe cases, explosive and destructive behaviors occur across all settings.

Affective aggression may be escape-motivated, while aggression often occurs in compulsive individuals when demands are placed on them to end a preferred activity. On the other hand, as in one subject in the present series, subjects with extreme hyperactivity may exhibit aggressive and destructive behaviors with such high frequency as to comprise a challenge to accurate measurement. Subgroups of aggressive youth may be identified in future studies, with each category having similar dimensions in terms of antecedents, topography, intervention methods, and neurobiology. Ratings that employ directly observed and recorded information may afford closer study of the efficacy of different treatments and strategies for the prevention of aggression in this population.

The present study is ongoing, with a goal of 30 patients in total, and the full analysis will be performed on the total number of subjects once the study is completed. Clinical diagnostic information, scores, and details of the aggression and self-injury may prove useful in the formulation of hypotheses for future studies involving this population.

CONCLUSION

Aggression is a common and serious problem among youth with developmental disabilities. Instruments for accurately recording and objectively measuring and studying aggression in this population and in outpatients are urgently needed. In this preliminary study, the OAS direct measure of aggression showed significant correlation with the already validated ABC-C irritability subscale in a sample of eight children and adolescents with autistic disorder, mental retardation, and aggression. Further study is warranted, and the behavioral antecedents for each episode should be explored.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Edwin Cook for mentoring and Stacey Ward for layout and typing.

This study was supported by NIMH grant K08 MH-01516 and NICHD grant 3P01 HD-26927-0752, and by a $5,000 unrestricted grant from Abbott Pharmaceuticals.

|

|

|

|

1 Kafantaris V, Lee DO, Magee H, et al: Assessment of children with the Overt Aggression Scale. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:186–193Link, Google Scholar

2 Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76–338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar

3 Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, et al: Psychometric characteristics of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist. Am J Ment Defic 1985; 89:492–502Medline, Google Scholar

4 Aman MG, Tasse MJ, Rojahn J, Hammer D: The Nisonger CBRF: a child behavior rating form for children with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 1996; 17:41–57Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, et al: The Overt Aggression Scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:35–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Silver JM, Yudofsky SC: The Overt Aggression Scale: overview and guiding principles. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:S22-S29Google Scholar

7 Lord C, Rutter M, LeCouteur A: Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 1994; 24:659–685Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Lord C, Rutter M, Goode S, et al: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: a standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. J Autism Dev Disord 1989; 19:185–212Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Hellings JA: Treatment of comorbid disorders in autism: which regimens are effective and for whom? http://www.autisme.qc.ca/comprendre/docViewing.php?section=comprendre&noCat=5&noDoc=88Google Scholar