The Effect of Major Depression on Subjective and Objective Cognitive Deficits in Mild to Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury

Abstract

The effect of major depression on subjective and objective cognitive deficits 6 months following mild to moderate traumatic brain injury (TBI) was assessed in 63 subjects. Patients with subjective cognitive complaints (n=63) were more likely to be women, with higher Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores and have a diagnosis of major depression. They also performed significantly more poorly on various measures of memory, attention and executive functioning. Group differences on most but not all cognitive measures disappeared in a multivariate analysis when controlling for depression. In mild to moderate TBI, subjective cognitive deficits are linked in large measure to comorbid major depression. However, other mechanisms may also account for these deficits.

Cognitive deficits following traumatic brain injury (TBI) include impairments in attention, memory and executive functioning.1–7 Patients who perform poorly on various batteries of neurocognitive testing often complain of these difficulties.8–10 However, the association between self-reported cognitive symptoms and performances on objective cognitive tests has not been consistently supported by empirical data. Some investigators have concluded that subjective cognitive complaints were not always related to neuropsychological test performance11–13 but rather to emotional difficulties.14,15 However, other studies have failed to find an association between objective measures of cognitive dysfunction and emotional distress.16,17 These conflicting results may be due to differing methods of evaluating self-report symptoms and objective cognitive impairment, the heterogeneity of TBI subjects in terms of trauma severity and varying periods of assessment following head injury.

Despite the mounting evidence suggesting a strong association between clinically diagnosed major depression and poor performance on cognitive testing following mild to moderate TBI,18–23 the few studies14,16 that have investigated the relationship between self-reported cognitive difficulties, neuropsychological test performances and emotional complaints, have relied mainly on subjective measures of depression or on instruments that assess psychological profiles in order to detect comorbid depressive symptoms. Additionally, they have neglected to control for depression when investigating whether subjective cognitive complaints accurately reflected cognitive dysfunction on objective testing.

The focus of the current study was to investigate the relationship between cognitive impairment assessed by standard neuropsychological tests and subjective cognitive complaints based on a self-report questionnaire in mild to moderate TBI 6 months following head injury. The effect of clinically diagnosed major depression on subjective (self-report) and objective (neuropsychological testing) indices of cognitive impairment was also explored.

METHOD

Patient Selection

The study population consisted of 63 TBI patients who were recruited consecutively from a traumatic brain injury clinic at a tertiary care referral center. The subjects had either sustained a mild head injury24 (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS]=13–15; loss of consciousness [LOC] <20 minutes; posttraumatic amnesia [PTA] < 24 hours) or moderate TBI (GCS=9–12; PTA>24 hours but less than 1 week) and were between 18 to 60 years of age. All participants had a detailed neuropsychiatry examination at 6 months posthead injury before undergoing a battery of cognitive tests. The presence of posttraumatic “subjective cognitive” difficulties was determined by patients’ response on three questions of the Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ): “forgetfulness, poor memory”, “poor concentration” and “taking more time to think”. These selected items are the only questions from the RPQ that focus on cognition. The RPQ has been shown to be a valid measure of symptoms commonly experienced following head injury.25

Written consent was provided from all subjects and institutional ethics board approval was obtained for this study.

Data Collection

Background information.

All subjects were seen 6 months following a mild to moderate TBI. The collected demographic and TBI-related data were: age, gender, marital and preinjury employment status, educational level, problem drinking (based upon the CAGE questionnaire26 and amount of alcohol consumed per week), past psychiatric history, prior head injury and mechanism of injury. Psychotropic and/or analgesic medication use was also recorded given the CNS depressant properties of these drugs potentially impairing cognition. For head injury severity, the following were obtained: initial GCS recorded in the emergency room, LOC and PTA duration, and initial CT brain results.

Diagnosis of Major Depression

The study participants were interviewed with the mood disorder section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Disorders (SCID27 for DSM–IV) to establish a diagnosis of major depression. The clinic’s neuropsychiatrist who conducted the interview was blind to the subjects’ cognitive data.

Neuropsychological Tests

The neuropsychological battery comprised 10 tests known to be sensitive to cognitive changes following TBI. They included indices of attention/working memory (Weschsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III [WAIS-III]28—working memory, verbal memory (California Verbal Learning Test [CVLT-II]29—total, long delay free recall and recognition hits), visuospatial learning and memory (Brief Visuospatial Memory Test—Revised [BVMT-R]30—immediate and delay total recall), information processing speed and sustained and divided attention (Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task [PASAT]31 at increasingly quicker rate of number presentation: 2.0 and 1.2 sec.), executive functioning (Wisconsin Card Sorting Test [WCST]32—total and perseverative responses). The Vocabulary subscale of the Wechsler Abbreviated Intelligence Scale (WASI)33 was used to provide an estimate of the premorbid IQ and the Word Memory Test (WMT)34 was administered to assess subject compliance and effort with testing.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analyses.

Patients with and without subjective cognitive complaints were compared using two-tailed t tests for continuous variables, and χ2 analyses for categorical variables. Fisher’s exact test was reported when appropriate. For the cognitive data, raw scores were used for analysis.

Multivariate analyses.

A multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was performed using the variables found statistically significant (p≤0.05) on univariate analyses. Subject grouping was designated as the fixed factor and seven of the cognitive tasks were entered as dependent variables. Two separate MANCOVAs were then computed across groups for each of the cognitive measures, one adjusting for gender and injury severity as measured by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score and the other for depression (SCID for DSM–IV) in addition to gender and GCS score.

RESULTS

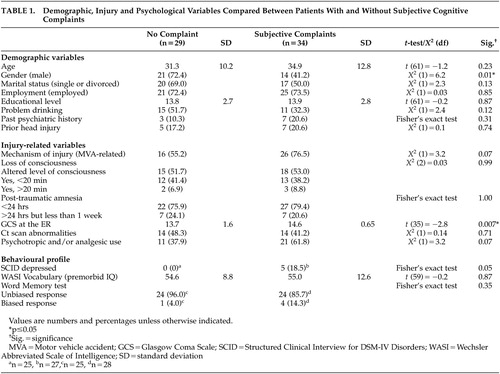

Demographic and Injury-Related Data

The mean age of the 63 patients enrolled in the study was 33 years (SD=11.7) and 55.6% were male. Thirty-four (54%) subjects reported subjective cognitive complaints on the RPQ. There were no differences in terms of demographic and injury-related variables between the two groups, except that those with subjective cognitive complaints had a higher GCS (t=−2.8, df=35, p=0.007) and were more likely to be women (χ2=6.2, df=1, p=0.01) (Table 1).

Major Depression

Based on the SCID for DSM–IV, major depression occurred in 18.5% of the group with subjective cognitive complaints but in none of those without self-reported cognitive difficulties. The difference between the two groups was significant (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.05) (Table 1).

Neurocognitive Deficits

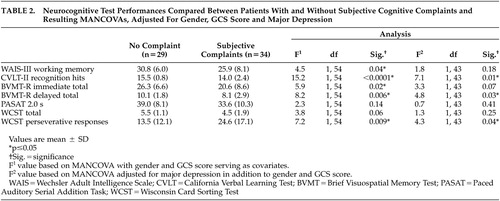

While both groups had similar scores on their premorbid IQ and on the WMT (Table 1), patients with subjective complaints scored significantly more poorly on measures of working memory (WAIS-III) (t=2.7, df=60, p=0.01), verbal (CVLT-II recognition hits) (t=3.4, df=42, p=0.001) and visuospatial memory (BVMT-R immediate [t=2.9, df=59, p=0.005] and delayed total recall [t=3.2, df=54, p=0.002]), attention and information processing speed (PASAT 2.0 s) (t=2.2, df=57, p=0.03), and executive functioning (WCST total [t=2.4, df=51, p=0.02] and perseverative responses [t=−2.9, df=56, p=0.005]). There were no significant group differences on the CVLT-II total (t=1.7, df=61, p=0.09) and long delay free recall (t=1.4, df=53, p=0.18) or on the PASAT at 1, 2 presentation interval (t=1.8, df=56, p=0.07).

When using MANCOVA on cognitive variables found statistically significant during univariate analysis, with gender and GCS score serving as covariates, the differences between the groups remained significant on almost all cognitive measures: WAIS-III working memory (F=4.5, df=1,54, p=0.04), CVLT-II recognition hits (F=15.2, df=1,54, p<0.0001), BVMT-R immediate (F=5.9, df=1,54, p=0.02) and delayed total recall (F=8.2, df=1,54, p=0.006), and WCST perseverative responses (F=7.2, df=1,54, p=0.009). In a separate MANCOVA, adjusted for depression in addition to gender and GCS score, those with subjective cognitive complaints scored significantly more poorly only on CVLT-II recognition hits (F=7.1, df=1,54, p=0.01), BVMT-R delayed total recall (F=4.8, df=1,54, p=0.03) and WCST perseverative responses (F=4.3, df=1,54, p=0.04) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that patients with mild to moderate TBI, who reported cognitive difficulties at 6 months following injury, performed more poorly on objective neuropsychological testing than those without subjective cognitive complaints. This finding concurs with certain previous mild TBI studies8–10 and has also been described in patients with HIV35,36 and in subjects with multiple sclerosis.37,38

The potential contribution of other factors such as prior head injury and psychotropic and/or analgesic medication intake to subjects’ performances on cognitive testing was also assessed. Lack of statistically significant differences between the two groups on all these variables eliminated the possibility of these factors influencing cognitive performance. Also, no differences were noted in terms of CT scan results, a finding that is significant given the association between neuropsychological deficits and CT scan abnormalities in patients with these injuries.39

Our study also clarified contradictory findings from previous investigations14,16 where the influence of psychological distress on cognition was evaluated based solely on self-report instruments of depression. Once major depression (according to DSM–IV criteria) was controlled for, the differences between those with and without subjective cognitive complaints disappeared on most cognitive tests, indicating a close association between objective measure of mood (SCID-IV) and several aspects of cognition.

However, depression did not account for all subjective reporting of cognitive difficulties in our study since, even after adjusting for low mood, significant differences remained between those with and without subjective cognitive complaints. Some of these individuals with self-reported cognitive difficulties may be part of the “miserable minority,” a term coined by Ruff et al.40 to describe mild TBI patients whose recovery is compromised by psychological factors other than depression, such as premorbid personality traits. Recent data from functional imaging studies41–45 suggest an alternative hypothesis—namely that, in certain patients with mild TBI, cognitive complaints may relate directly to cerebral dysfunction that can be unmasked by neuroimaging activation paradigms. Ruff et al.41 studied nine mild head injury patients with persistent complaints and measurable cognitive deficits, who underwent 18-Fluoro-deoxyglucose (FDG) PET, a mean of 29 months postaccident. Despite normal MRI/CT scans, the TBI subjects, when matched against healthy comparison subjects, demonstrated frontal and temporal hypometabolism while performing a visual sustained attention task. Alterations at the level of cerebral substrate have been documented even in acute cases of mild TBI (i.e., within 1 month of injury) using the fMRI approach. In response to increasing working memory (WM) processing load42–43 as well as to tasks that probe episodic memory,44 subjects with mild head injury have shown significant differences in brain activation patterns, relative to healthy comparison subjects, differences that may explain mild TBI patients’ persistent cognitive complaints and need to exert greater effort during cognitive tasks.45

CONCLUSION

In summary, mild to moderate TBI patients with persisting subjective cognitive complaints have demonstrable evidence of cognitive dysfunction. In most, but not all patients, these objective cognitive difficulties are linked to comorbid major depression. This clinically important observation suggests that a detailed assessment of mood based on objective criteria should be considered in all patients who complain of cognitive problems following such injuries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Feinstein is supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant #36535)

The poster presentation of this study was given at the 15th Annual Meeting of the American Neuropsychiatric Association in Bal Harbour, Fl., February 21-24, 2004.

|

|

1 Gasquoine PG: Postconcussion symptoms. Neuropsychol Rev 1997; 7:77–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Brooks J, Fos LA, Greve KW, et al: Assessment of executive function in patients with mild traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 1999; 46:159–163Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Cicerone KD, Azulay J: Diagnostic utility of attention measures in postconcussion syndrome. Clin Neuropsychol 2002; 16:280–289Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Mangels JA, Craik FIM, Levine B, et al: Effects of divided attention on episodic memory in chronic traumatic brain injury: a function of severity and strategy. Neuropsychologia 2002; 40:2369–2385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Stuss DT, Ely P, Hugenholtz H, et al: Subtle neuropsychological deficits in patients with good recovery after closed head injury. Neurosurgery 1985; 17:41–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Wiegner S, Donders J: Performance on the wisconsin card sorting test after traumatic brain injury. Assessment 1999; 6:179–187Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 McCullagh S, Feinstein A: Cognitive Changes, in Textbook of Traumatic Brain Injury, first edition. Silver JM, McAllister TW, Yudofsky SC (eds.), Washington, DC American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 2005Google Scholar

8 Leininger BE, Gramling SE, Farrell AD, et al: Neuropsychological deficits in symptomatic minor head injury patients after concussion and mild concussion. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990; 53:293–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Bohnen N, Jolles J, Twijnstra A: Neuropsychological deficits in patients with persistent symptoms six months after mild head injury. Neurosurgery 1992; 30:692–696Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Bernstein DM: Information processing difficulty long after self-reported concussion. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2002; 8:673–682Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Sunderland A, Harris JE, Baddeley AD: Do laboratory test predict everyday memory? A neuropsychological study. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav 1983; 22:341–357Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Kapur N, Pearson D: Memory symptoms and memory performance of neurological patients. Br J Psychol 1983; 74:409–415Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Lannoo E, Colardyn F, Vandekerckhove T, et al: Subjective complaints versus neuropsychological test performance after moderate to severe head injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998; 140:245–253Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Gass CS, Apple C: Cognitive complaints in closed-head injury: relationship to memory test performance and emotional disturbance. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1997; 19:290–299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Satz P, Forney DL, Zaucha K, et al: Depression, cognition, and functional correlates of recovery outcome after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 1998; 12:537–553Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Bohnen NI, Jolles J, Twijnstra A, et al: Late neurobehavioural symptoms after mild head injury. Brain Inj 1995; 9:27–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Raskin SA, Mateer CA, Tweeten R: Neuropsychological assessment of individuals with mild traumatic brain injury. Clin Neuropsychol 1998; 12:21–30Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Barth JT, Macciocchi SN, Giordani B, et al: Neuropsychological sequelae of minor head injury. Neurosurgery 1983; 13:529–533Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Bornstein RA, Miller HB, van Schoor TJ: Neuropsychological deficit and emotional disturbance in head-injured patients. J Neurosurg 1989; 70:509–513Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Levin HS, Brown SA, Song JX, et al: Depression and posttraumatic stress disorder at three months after mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2001; 23:754–769Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Fann JR, Uomoto JM, Katon WJ: Cognitive improvement with treatment of depression following mild traumatic brain injury. Psychosomatics 2001; 42:48–54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Moser D, et al: Major depression following traumatic brain injury. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:42–50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Rapoport M, McCullagh S, Shammi P, et al: Cognitive impairment associated with major depression following mild and moderate traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 17:61–65Link, Google Scholar

24 The Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee of the Head Injury Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine: Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1993;8:86-87Google Scholar

25 King NS, Crawford S, Wenden FJ, et al: The rivermead post concussion symptoms questionnaire: a measure of symptoms commonly experienced after head injury and its reliability. J Neurol 1995; 242:587–592Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P: The cage questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry 1974; 131:1121–1123Medline, Google Scholar

27 First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV diagnoses (SCID): Clinician and research versions. Version 2.0. New York NY, Biometrics Research Department, 1996Google Scholar

28 Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third ed. (WAIS-III). San Antonio, Tex, The Psychological Corporation, 1997Google Scholar

29 Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, et al: California Verbal Learning Test-2nd ed. (CVLT-II). San Antonio, Tex, The Psychological Corporation, 2000Google Scholar

30 Benedict RHB: Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (BVMT-R). Odessa, Fla, The Psychological Corporation, 1997Google Scholar

31 Gronwall DMA: Paced auditory serial-addition task: a measure of recovery from concussion. Percept Mot Skills 1977; 44:367–373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Heaton RK, Chelune G, Talley J, et al: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc, 1993Google Scholar

33 Wechsler D: Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence(WASI). San Antonio, Tex, The Psychological Corporation, 1999Google Scholar

34 Green WP, Allen LM, Astner K: The Word Memory Test: A user’s guide to the oral and computer-administered forms (WMT). U.S Version 1.1. Durham, N.C, CogniSyst, Inc, 1996Google Scholar

35 Beason-Hazen S, Nasrallah HA, Bornstein RA: Self-report of symptoms and neuropsychological performance in asymptomatic HIV-positive individuals. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:43–49Link, Google Scholar

36 Poutiainen E, Elovaara I: Subjective complaints of cognitive symptoms are related to psychometric findings of memory deficits in patients with HIV-1 infection. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1996; 2:219–225Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Kujala P, Portin R, Ruutiainen J: Memory deficits and early cognitive deterioration in MS. Acta Neurol Scand 1996; 93:329–335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Taylor R: Relationships between cognitive test performance and everyday cognitive difficulties in multiple sclerosis. Br J Clin Psychol 1990; 29:251–252Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 Williams DH, Levin HS, Eisenberg HM: Mild head injury classification. Neurosurgery 1990; 27:422–428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 Ruff RM, Camenzuli L, Mueller J: Miserable minority: emotional risk factors that influence the outcome of a mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 1996; 10:551–565Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Ruff RM, Crouch JA, Tröester AI, et al: Selected cases of poor outcome following mild brain trauma: comparing neuropsychological and positron emission tomography assessment. Brain Inj 1994; 8:297–308Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 McAllister TW, Saykin A, Flashman LA, et al: Brain activation during working memory 1 month after mild traumatic brain injury: a functional MRI study. Neurol 1999; 53:1300–1308Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 McAllister TW, Sparling MB, Flashman LA, et al: Differential working memory load effects after a mild TBI. Neuroimage 2001; 14:1004–1012Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 McAllister TW, Sparling MB, Flashman LA, et al: Reduction in episodic memory circuitry is related to traumatic brain injury severity. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:141Google Scholar

45 McAllister TW, Flashman LA, Sparling MB, et al: Working memory deficits after traumatic brain injury: catecholaminergic mechanisms and prospects for treatment-a review. Brain Inj 2004; 18:331–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar