Cognitive Reserve and the Relationship Between Depressive Symptoms and Awareness of Deficits in Dementia

Factors associated with impaired awareness in dementia include the presence of low cognitive reserve and depression. Better awareness of deficits in dementia is related to higher cognitive reserve. 7 Cognitive reserve theory proposes that premorbid factors (e.g., high level of education, occupational attainment, or level of literacy) 8 , 9 buffer against cognitive impairment, allowing the presentation of patients with the same brain disease to vary according to premorbid cognitive capacity. 10 Depression has also been linked with impaired awareness. The notion that greater awareness of deficits might lead to increased depression is intuitive, and in fact, previous work has found that increased depression is associated with greater awareness in dementia, although this relationship is not consistently replicated. 11 Smith and colleagues offer several explanations for discrepancies in the literature, including focus on diagnosis of major depression versus depressive symptoms, small sample sizes, and differential assessment of depressive symptoms. Other factors, such as cognitive reserve, may also account for inconsistent findings.

Although both cognitive reserve and depression have been independently linked to awareness, their relative contributions have never been examined. Given inconsistent studies on the relationship between awareness and depression, and the positive relationship between cognitive reserve and awareness of impairments, it is possible that level of cognitive reserve affects the relationship between awareness and depression. For example, there is evidence that individuals with higher cognitive reserve are more likely to participate in cognitively stimulating or complex activities. 12 As a result, it is plausible that these individuals are more likely to encounter cognitive difficulties, thereby increasing awareness of deficits and associated negative affect.

The current study investigated the role of depressive symptoms and cognitive reserve in awareness in questionable and mild stages of dementia. We measured cognitive reserve using single word-reading performance, lack of awareness using the discrepancy between an informant and the participant on a cognitive complaint inventory, and depressive symptoms using a self-report inventory. Our hypothesis was that cognitive reserve would predict awareness of deficits and differentially impact the relationship between depression and awareness.

METHOD

Participants

The current study included 66 community-dwelling individuals referred to an outpatient memory clinic for neuropsychological evaluation, who were subsequently diagnosed with questionable or mild dementia. We included patients in the study if they had a global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) 13 score of 0.5 (questionable dementia) or 1 (mild dementia) and had a close relative or friend to act as informant. The sample was evenly split between males and females (50% each). Racial composition of the sample was predominantly Caucasian (98%). Participants ranged in age from 56 to 92, with an average age of 74.65 (SD=6.71) years. Educational level ranged from 7 to 20 years, with an average of 13.47 (SD=2.95) years of education. Informants were the participant’s spouse (45%) or a child/other close relative or friend (55%). Diagnosed etiologies of cognitive impairment were: mild cognitive impairment/questionable dementia (N=31), probable Alzheimer disease (N=18), vascular dementia (N=9), mixed Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia (N=4), dementia secondary to movement disorder (N=2), and other (N=2).

Instruments

We used the 26-item version of the Cognitive Difficulties Scale (CDS; Patient and Informant Versions) 1 , 14 to measure awareness. The CDS includes items related to difficulties in attention, concentration, orientation, memory, praxis, language, and daily functioning, and asks the respondent to rate on a Likert scale how often (from 0=“not at all” to 4=“very often”) he or she has had difficulty on various tasks in the past month. It has adequate psychometric properties, including high correlation with performance on neuropsychological measures of memory and attention (r=−0.51), 15 good test-retest reliability (r=0.77), 14 and strong correlation between the 26-item and full length forms (r=0.90). 1 We defined lack of awareness as discrepancy between informant ratings on the family version of the CDS and participant ratings on the self-report version of the CDS (i.e., informant minus patient ratings) 1 because previous research indicates informant ratings of cognitive difficulties correlate more highly with actual performance-based testing than do dementia patient self-ratings. 7 Items missing data from either respondent of the participant-informant pair were omitted from both, and the average item discrepancy of the remaining items was the primary measure of awareness of deficits.

We used the Reading subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT) 16 , 17 to measure cognitive reserve. Patients completed the WRAT-R or WRAT-III reading subtest, depending on when they were seen. The two tests are highly interrelated. 17 Psychometric properties are good, with high internal consistency of the reading subtest (WRAT-R r=0.93–0.98; WRAT-III r=0.91–0.97) and excellent test-retest reliability (WRAT-R r=0.94; WRAT-III r=0.91–0.98). Previous research has utilized WRAT reading as a measure of cognitive reserve, 9 and it is the preferred measure of premorbid verbal intelligence, as it better estimates lower ranges of verbal intelligence than other similar measures. 18 A score of 100 is average performance on the WRAT reading subtest.

We used the Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II) 19 to measure depressive symptomatology. The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report measure that assesses the presence and severity of depression. Items on this scale reflect typical symptoms of depression, including affective, cognitive, and vegetative features. The psychometric properties of the BDI-II are good, with high internal consistency (α=0.92−0.93) and good criterion validity (HRSD-R, r =0.71). 19

Finally, we used the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) 20 as a brief measure of current global cognition. The 3MS is an extended Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) 21 that includes birthplace and date, semantic fluency, abstract reasoning, and delayed word recall. It has a maximum score of 100 points. The 3MS is a good screening tool for dementia, with excellent test-retest reliability in dementia patients (r=0.93 after 98 days) and 88% sensitivity, 90% specificity, 29% positive predictive value, and 90% negative predictive value. 22

RESULTS

Description of Primary Measures

In the overall sample, CDS discrepancy ranged from −1.32 to 3.04, with an average of 0.30 (SD=0.87). 3MS scores ranged from 60 to 98, with an average of 84.53 (SD=8.49). WRAT reading scores ranged from 77 to 122, with an average of 103.03 (SD=12.04). BDI-II scores ranged from 0 to 45, with an average of 6.80 (SD=7.36).

Correlations Between CDS Discrepancy and MMSE/3MS: Validity Check of Unawareness Measure

As expected, informant ratings significantly correlated with performance on the 3MS, r=−0.27, two-tailed p<0.05, and MMSE, r=−0.28, two-tailed p<0.05, indicating greater report of cognitive impairment by the informant was associated with poorer cognitive performance. In contrast, patient self-ratings were uncorrelated with performance on 3MS, r=0.01, two-tailed p=ns, and MMSE, r=0.07, two-tailed p=ns.

Heirarchical Regression Analysis

Hierarchical regression analysis with CDS discrepancy (unawareness) as the dependent variable was used to determine relative contributions of cognitive reserve, depressive symptoms, and their interaction. We entered variables in the following order: 3MS (to control for the severity of dementia), WRAT reading, BDI-II, and the WRAT reading/BDI-II interaction. Variables were centered to reduce multicollinearity.

Analyses demonstrated that WRAT reading accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in CDS discrepancy above and beyond contribution of 3MS, ΔR 2 =0.08, F (1, 63)=6.32, two-tailed p<0.01, although BDI-II did not significantly contribute to CDS discrepancy, ΔR 2 =0.00, F (1, 62)=0.01, two-tailed p=ns. These findings were qualified by an interaction between WRAT reading and BDI-II on CDS discrepancy, ΔR 2 =0.09, F (1, 61)=7.52, two-tailed p<0.05.

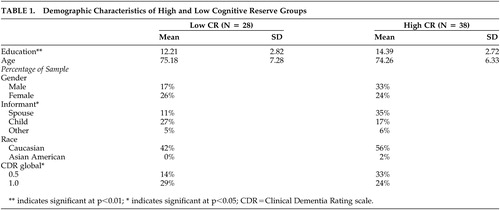

To further investigate this interaction, we split the overall sample into high (high cognitive reserve=WRAT reading>100) and low cognitive reserve groups (low cognitive reserve=WRAT reading<100) groups. Fisher’s z[prime] transformation 23 comparison of the depression and CDS discrepancy zero-order correlations between low and high cognitive reserve groups revealed a significant difference (high cognitive reserve: r=−0.34, p<0.05; low cognitive reserve: r=0.35, p=ns), z=2.79, two-tailed p<0.05. These correlations indicate that increased depressive symptoms are associated with decreased discrepancy between the informant and participant (i.e., better awareness) in high cognitive reserve individuals, but this relationship was not significant in low cognitive reserve individuals.

To ensure the robustness of this follow-up finding, we examined demographic differences between the high and low cognitive reserve groups ( Table 1 ). As expected, significant differences between the high and low cognitive reserve groups emerged for level of education, t (64)=−3.17, two-tailed p<0.01, with higher education in the high cognitive reserve group, providing evidence for divergent validity of the groups. The groups did not differ significantly in age, gender, or race. However, CDR scores differed between groups, with individuals meeting criteria for questionable dementia more likely to be in the high cognitive reserve group χ 2 (66)=4.29, two-tailed p<0.05. To ensure stability of the findings in light of the group difference in CDR scores, we conducted partial correlations accounting for 3MS performance. The partial correlations indicated the same pattern found in the zero-order correlations holds after controlling for performance on a measure of current global cognition (high cognitive reserve: partial r=−0.33, two-tailed p<0.05; low cognitive reserve: partial r=0.29, two-tailed p=ns). These correlations suggest that even when current global cognition is accounted for, higher levels of depressive symptoms are associated with less discrepancy in ratings of cognitive difficulties between the informant and high cognitive reserve participants. In low cognitive reserve individuals, the relationship between depressive symptoms and lack of awareness of cognitive difficulties remained nonsignificant, even after accounting for performance on a measure of current global cognition.

|

DISCUSSION

The findings from the current study suggest cognitive reserve moderates the relationship between depressive symptoms and lack of awareness of deficits in dementia. Specifically, this study revealed that cognitive reserve accounts for a significant proportion of the variance in unawareness, although depressive symptoms alone did not. Moreover, the interaction between cognitive reserve and depressive symptoms was significantly related to lack of awareness; increased awareness of cognitive deficits was related to greater depressive symptoms in individuals with higher cognitive reserve, even after controlling for global cognitive decline.

These findings may help explain discrepancies in the literature regarding the relationship between depression and awareness in dementia 8 since sample differences in cognitive reserve could impact the nature of the observed relationship. One explanation for the findings in the high cognitive reserve group is that they may be more cognitively active, and possibly more likely to encounter cognitive challenges that lead to frustration and awareness of deficits, in turn contributing to depressive symptoms. It also raises the question of degree of psychological mindedness, as those with higher cognitive reserve may be more self-reflective and such self-reflection may lead to greater depression, although we are aware of no literature indicating that this is the case. In contrast, there was not a significant relationship between awareness and depressive symptoms in the low cognitive reserve group. The sample size of this group was slightly smaller, and the strength of the correlation was similar to (although in the opposite direction of) the relationship detected in the high cognitive reserve group. This may suggest that depression obscures awareness in individuals with lower cognitive reserve; however, given that this finding was not statistically significant, it must be interpreted cautiously and replicated in a larger sample.

In addition to the primary analyses, informant ratings of cognitive difficulties were related to actual performance on a global cognitive screening measure, whereas patient self-ratings were not. This finding lends further support to previous studies indicating that informants are more accurate than patients themselves in rating their cognitive difficulties, supporting the validity of the informant-patient discrepancy as a measure of poor awareness. There were significant differences in informant type between the low and high cognitive reserve groups, with a larger proportion of spouses than children in the high cognitive reserve group, and the opposite pattern in the low cognitive reserve group. Although this raises the question of a possible confound, previous research 7 indicates no main effect of informant type (i.e., spouse versus child/other) on awareness in high versus low cognitive reserve groups, suggesting that the informant difference in groups should not impact overall findings.

One strong point of this study is the “generalizability” to the clinical setting because it was conducted utilizing data collected in a clinical practice. The measures used were part of a standard neuropsychological battery, and were intentionally brief. The use of the discrepancy between informant and patient ratings on a cognitive complaint inventory is a simple approach to measurement of awareness problems that can easily be employed in a clinical setting. The current study may have been limited by use of self-report questionnaire of depressive symptoms, rather than a clinician-rated interview, in addition to the cross-sectional methodology, which does not allow examination of cognitive change as a function of cognitive reserve. In addition, the current study examined only early stages of dementia (i.e., questionable and mild dementia), and as such, these results may not generalize to later stages of dementia. Future research may benefit from incorporating longitudinal methods, utilizing more comprehensive measures of depressive symptomatology and awareness, examining these factors in a broader range of dementia severity, and obtaining a larger sample size that would allow path analysis to further investigate directionality of the relationships between cognitive reserve, depression, and awareness.

In summary, our study expands the current literature on the relationship between depressive symptoms and awareness of deficits in dementia, providing evidence that this relationship is moderated by level of cognitive reserve. These findings provide several avenues for possible future research, including investigating the manner in which cognitive reserve contributes to the relationship between depressive symptoms and awareness in dementia.

1. Derouesné C, Thibault S, Lagha-Pierucci S, et al: Decreased awareness of cognitive deficits in patients with mild dementia of the alzheimer’s type. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999; 14:1019–1030Google Scholar

2. Seltzer B, Vasterling J, Buswell, A: Awareness of deficit in Alzheimer’s disease: association with psychiatric symptoms and other disease variables. J Clin Geropsychology 1995; 1:79–87Google Scholar

3. Seltzer B, Vasterling J, Mathias CW et al: Clinical and neuropsychological correlates of impaired awareness of deficits in Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease: a comparative study. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2001; 14:122–129Google Scholar

4. Zanetti O, Vallotti B, Frisoni GB, et al: Insight in dementia: When does it occur? Evidence for a non-linear relationship between insight and cognitive status. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1999; 100–106Google Scholar

5. Cotrell V, Wild K: Longitudinal study of self-imposed driving restrictions and deficits in awareness in patients with alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1999; 13:151–156Google Scholar

6. Seltzer B, Vasterling J, Yoder J, et al: Awareness of deficit in Alzheimer’s disease: relation to caregiver burden. Gerontologist 1997; 37:20–24Google Scholar

7. Spitznagel MB, Tremont G: Cognitive reserve and anosognosia in questionable and mild dementia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2005; 20:505–515Google Scholar

8. Manly JJ, Touradji P, Tang MX, et al: Literacy and memory decline among ethnically diverse elders. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2003; 25:680–690Google Scholar

9. Stern Y, Albert S, Tang MX, et al: Rate of memory decline in AD is related to education and occupation: CR? Neurology 1999; 53:1942–1947Google Scholar

10. Satz P: Brain reserve capacity on symptom onset after brain injury: a formulation and review of evidence for threshold theory. Neuropsychology 1993; 7:273–295Google Scholar

11. Smith CA, Henderson VW, McCleary CA, et al: Anosognosia and Alzheimer’s disease: the role of depressive symptoms in mediating impaired insight. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2000; 22, 437–444Google Scholar

12. Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA: Assessment of lifetime participation in cognitively stimulating activities. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2003; 25:634–642Google Scholar

13. Morris JC: The clinical dementia rating: current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993; 43:2412–2414Google Scholar

14. McNair DM, Kahn RJ: Self-assessment of cognitive deficits, in Assessment in Geriatric Psychopharmacology. Edited by Crook T, Ferris S, Bartus R. New Canaan, Conn, Mark Powley, 1984Google Scholar

15. Gass CS, Apple C: Cognitive complaints in closed-head injury: relationship to memory test performance and emotional disturbance. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1999; 19:290–299Google Scholar

16. Jastak S, Wilkinson GS: The Wide Range Achievement Test-Revised: Administration Manual. Wilmington, Del, Jastak Associates, 1984Google Scholar

17. Wilkinson, GS: The Wide Range Achievement Test-3: Administration Manual. Wilmington, Del, Wide Range, 1993Google Scholar

18. Johnstone B, Callahan CD, Kapila CJ, et al: The comparability of the WRAT-R reading test and NAART as estimates of premorbid intelligence in neurologically impaired patients. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 1996; 11:513–519Google Scholar

19. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK: Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd ed. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1996Google Scholar

20. Teng EL, Chiu HC, Schneider LS, et al: Alzheimer’s dementia: performance on the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Consult Clin Psychol 1987; 55:96–100Google Scholar

21. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-mental state” a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Google Scholar

22. Bland RC, Newman SC: Mild dementia or cognitive impairment: the modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) as a screen for dementia. Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46:506–510Google Scholar

23. Cohen J, Cohen P: Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1983Google Scholar