Sex-Dependent Hippocampal Volume Reductions in Schizophrenia Relate to Episodic Memory Deficits

The goals of our study were to investigate possible sex differences in hippocampal volume and episodic memory performance in schizophrenia and to analyze the relationship between memory performance in schizophrenia and hippocampal volumes.

METHOD

The sample comprised 21 inpatients (14 males, 7 females) who met DSM-IV criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia (SCID). Subjects with a history of head injury, neurological diseases, or substance dependence or abuse (SCID) were excluded. The mean duration of disorder was 8 (±9) years (females: 11±9; males: 7±9). Participants had experienced a mean of 3 (±2) previous hospitalizations (females: 3±2, males: 3±3). All subjects were on antipsychotic medication (mean chlorpromazine equivalent dose at testing was 501±416 mg/day; females: 419±356 mg/day, males: 542±450 mg/day). Male and female subjects with schizophrenia did not significantly differ on clinical variables (t tests, p>0.3 in all cases).

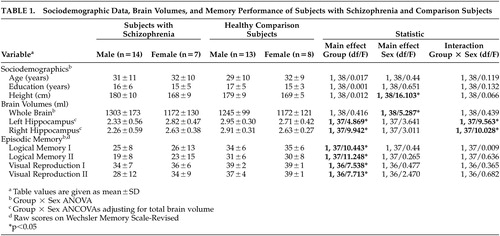

Subjects with schizophrenia were compared with 21 healthy comparison subjects without a history of neurological or psychiatric disorder who were closely matched for age, sex, years of education (full-time school and vocational/university education combined), height and handedness, and were paid for their participation. Sociodemographic data are separately given for group and gender in Table 1 . Group by gender analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed no differences between groups on these variables (p>0.5 in all cases). After complete description of the study informed written consent of all participants was obtained. The Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Marburg approved the study design.

|

All subjects received a magnetic resonance (MR) scan using a 1.5-Tesla clinical MRI scanner (Signa Horizon, General Electric Medical Systems) machine on the day of the assessment. Scanning parameters of the T 1 -weighted three-dimensional sequence (fast spoiled gradient recalled acquisition in the steady state; FSPGR) were as follows: TE=4.2 msec, TR=9 msec; flip angle=20 o ; number of excitations=3, FOV=25×19; slice plane=axial; matrix=256×256; slice thickness=1.4 mm (no gap); slice number=120.

Volumetric analysis was done on the basis of the individual 3D-MR images using the CURRY ® software (version 4.5; Neurosoft, Inc., El Paso, Tex.). Images were reformatted into continuous slices of 1 mm thickness. Total brain volume was calculated with automated multistep algorithms and 3D region growing methods that are limited by gray value thresholds. Simultaneous 3D visualization of brain structures and manual tracing allowed a precise identification and delineation of regions of interest. The hippocampus was disarticulated from surrounding tissue on coronal slices by means of manual tracing according to a standardized protocol 8 and the serial sections provided by Duvernoy. 9 The protocol had been developed to reduce discrepancies in hippocampal measurements between researchers. A single trained rater (BN), who was blind to the subjects’ test performance and clinical diagnoses, completed the analyses. The intrarater reliability based on 12 randomly chosen cases was r=0.91 (intraclass correlation coefficient).

Clinical and cognitive assessment and MR imaging of schizophrenia subjects were performed in a clinically stable phase within 3 weeks after admission. Symptom severity was assessed at the time of testing by using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and resulted in a mean 80 (±26) total PANSS score. There was no significant difference between PANSS scores of female (87±34) and male (76±21) subjects (p>0.3). As episodic long-term memory is the cognitive function most severely disturbed in schizophrenia, and the one most closely related to hippocampal abnormalities, 2 , 3 episodic verbal and visual memory was chosen as the main cognitive outcome variable. It was assessed with the subtests Logical Memory I and II and Visual Reproduction I and II, respectively, from the German version of the Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised (WMS-R).

Principal statistical methods used were analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and Pearson’s correlations. Statistical comparisons were performed using the SPSS (SPSS for Windows, Version 12.0).

RESULTS

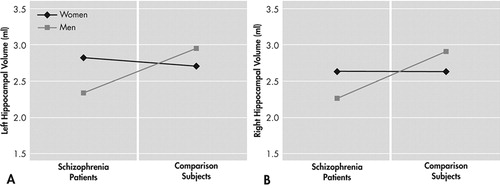

Two separate Group x Sex ANCOVAs comparing left and right hippocampal volume while adjusting for total brain volume revealed significant Group x Sex interactions for both hemispheres ( Table 1 ). Compared with male comparison subjects, male schizophrenia subjects had significantly smaller left (−21%) and right (−22%) hippocampal volumes. Hippocampal volume of female schizophrenia subjects did not differ from comparison subjects ( Figure 1 ).

Four separate 2 (Group) x 2 (Sex) ANOVAs comparing episodic memory performance revealed significant effects of Group (schizophrenia subjects showing lower performance on all four subtests) but no significant effect of Sex and no significant Group x Sex interaction ( Table 1 ).

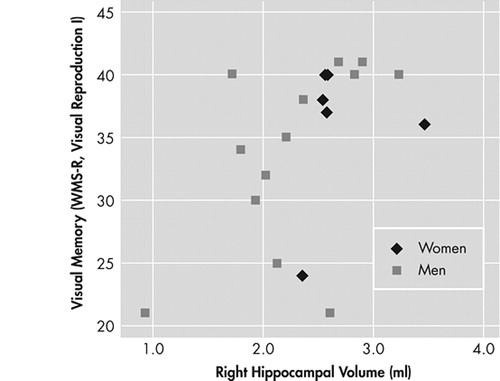

Larger right hippocampal volume of subjects with schizophrenia was significantly related to visual memory performance (WMS-R, Visual Reproduction I, r=0.502, p=0.029). However, this significant positive relationship for the whole group could be attributed to the association between hippocampal volume and visual memory in male schizophrenia subjects (r=0.54, p=0.055) rather than female subjects (r=0.228, p=0.664) ( Figure 2 ).

No other significant relationship emerged between hippocampal volumes and memory performance (p>0.2 in all cases). In subjects with schizophrenia psychopathological measures (PANSS total score and subscores) were not related to hippocampal volume (p>0.2 in all cases) or cognitive measures (p>0.6 in all cases). Antipsychotic dosage was neither related to cognitive nor morphometric variables (p>0.2 in all cases). An additional anticholinergic medication in four schizophrenia subjects did not compromise memory performance (U tests, p>0.2 in all cases).

DISCUSSION

We found bilateral hippocampal volume reductions in male schizophrenia subjects while hippocampal volumes of female schizophrenia subjects did not differ from female comparison subjects. These sex differences were not due to insufficient statistical power for the female subgroup: means of female schizophrenia subjects and female comparison subjects were virtually identical ( Table 1 ) and sample size—though low—was sufficient to detect differences of the magnitude found for male subjects (effect size d=1.38). Sex differences on hippocampal volumes were also not attributable to differing sociodemographic or clinical sample characteristics of male and female schizophrenia subjects. Nevertheless, small samples always carry the risk of sampling biases.

Volume reductions of the hippocampal formation in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia are a consistent finding in MRI research 1 , 10 but analyses have been mainly conducted with male subjects. Analyses of sexual dimorphism in schizophrenia hippocampal pathology have yielded inconsistent results with some studies reporting that male schizophrenia subjects are more affected, 4 and some finding no differences. 5 , 6 More pronounced brain abnormalities in male schizophrenia subjects have, however, repeatedly been found for other brain structures, namely the lateral ventricles and the whole temporal lobe. 11 Sex differences in brain pathology of schizophrenia subjects have been attributed to an interaction between pathophysiological mechanisms and normal sexual dimorphism in brain development. Within the framework of neurodevelopmental hypotheses of schizophrenia it has been proposed that hippocampal volume reductions in schizophrenia reflect early impact on the developing brain rather than a genetic predisposition. 12 Male brains might be more vulnerable to brain insults because of delayed lateralization and lack of protection from estrogen. 13

We could further show that reduced right hippocampal volumes in male schizophrenia subjects were specifically related to deficits of visual episodic memory. Reduced hippocampal volume might represent an anatomical substrate of deficient memory function in males with schizophrenia. A positive relationship between hippocampal volume and memory performance has been shown for other memory-impaired patient groups (e.g., premature born children) 14 but might be restricted to subjects with pathologically affected hippocampi. The fact that episodic memory deficits were also present in female schizophrenia subjects despite normal hippocampal volumes suggests that the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to memory deficits differ between the two sexes.

Small sample sizes in our study and acute illness state of schizophrenia subjects prevent firm conclusions from our results. However, our findings might stimulate further research relating to gender differences on morphometric and cognitive variables in schizophrenia. More research in larger and clinically stable outpatient populations is needed to confirm our findings.

1 . Nelson MD, Saykin AJ, Fleshman LA, et al: Hippocampal volume reduction in schizophrenia as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 53:433–440Google Scholar

2 . Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK: Neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology 1998; 12:426–445Google Scholar

3 . Cirillo MA, Seidman LJ: Verbal declarative memory dysfunction in schizophrenia: from clinical assessment to genetics and brain mechanisms. Neuropsychol Rev 2003; 13:43–77Google Scholar

4 . Bogerts B, Ashtari M, Degreef G, et al: Reduced temporal limbic structure volumes on magnetic resonance images in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1990; 35:1–13Google Scholar

5 . Gur RE, Turetsky BI, Cowell PE, et al: Temporolimbic volume reductions in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:769–775Google Scholar

6 . Szeszko PR, Goldberg E, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al: Smaller anterior hippocampus formation volume in antipsychotic-naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:2190–2197Google Scholar

7 . Antonova E, Sharma T, Morris RG, et al: The relationship between brain structure and neurocognition in schizophrenia: a selective review. Schizophr Res 2004; 70:117–145Google Scholar

8 . Pruessner JC, Li LM, Serles W, et al: Volumetry of hippocampus and amygdala with high-resolution MRI and three-dimensional analysis software: minimizing the discrepancies between laboratories. Cereb Cortex 2000; 10:433–442Google Scholar

9 . Duvernoy HM: The Human Hippocampus: Functional Anatomy, Vascularization, and Serial Sections with MRI, 2nd ed. Berlin, Springer, 1998Google Scholar

10 . Vita A, De Peri L, Silenzi C, et al: Brain morphology in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging studies. Schizophr Res 2006; 82:75–88Google Scholar

11 . Leung A, Chue P: Sex differences in schizophrenia, a review of the evidence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 101:3–38Google Scholar

12 . Schulze K, McDonald C, Frangou S, et al: Hippocampal volume in familial and nonfamilial schizophrenic probands and their unaffected relatives. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:562–570Google Scholar

13 . Seeman MV, Lang M: The role of estrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:185–194Google Scholar

14 . Isaacs EB, Lucas A, Chong WK, et al: Hippocampal volume and everyday memory in children of very low birth weight. Pediatr Res 2000; 47:713–720Google Scholar