The Clinician-Scientist in Neuropsychiatry

Abstract

Neuropsychiatric research seeks to improve the lives of patients with brain-based behavioral disturbances. There has been dramatic progress in diagnosis and treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders, and progress in neuroscience and biotechnology promises further success. Paradoxically, recent trends threaten to erode this progress. In this environment, neuropsychiatric clinician-scientists must advocate for the importance of research. This position statement defines neuropsychiatric research, describes current challenges to the neuropsychiatric clinician-scientist, summarizes research opportunities, describes how future neuropsychiatric clinician-investigators should be trained, and makes recommendations for promoting neuropsychiatric research.

Neuropsychiatry is a clinical discipline whose mission is to improve the health and quality of life of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders through better understanding of the etiology, pathogenesis, natural history, and treatment of brain disorders producing behavioral disturbances. Neuropsychiatry is based on disease models of mental illness, and it represents the successful application of advances in neuroscience to patient care by psychiatrists, behavioral neurologists, and neuropsychologists. Neuropsychiatry is primarily a clinical rather than a laboratory activity; its practitioners are clinicians, and the neuropsychiatric scientist is involved primarily with clinical research. Neuropsychiatry has new diagnostic tools and new therapeutic interventions that have greatly enhanced disease diagnosis and treatment, and it is well positioned to take advantage of further progress in basic neuroscience as these apply to clinical problems.

Neuropsychiatry is rapidly growing, as evidenced by the emergence of a national organization (the American Neuropsychiatric Association; ANPA), several journals devoted to the topic, many fellowships training neuropsychiatrists, and numerous clinical programs.1,2 Neuropsychiatry is enjoying a resurgence of interest because there is a pressing need and an exciting opportunity to bring discoveries in neuroscience to bear on human illnesses. Despite this renaissance in neuropsychiatry, the continued development of the discipline is threatened by changes in health care delivery and funding, shrinking budgets for research, changes in priorities in medical education, and attitudes that devalue the important contributions made by the clinician-scientist. The potential role of neuropsychiatric research in innovative health care delivery, improved quality of care, enhanced quality of life, and development of new treatments and technologies is under-recognized, and there is a need to champion this research with federal agencies, academic health centers, biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, managed care organizations, and the public.

Promoting the benefits of neuropsychiatric research and the role of the neuropsychiatric clinician-scientist is of special importance to ANPA and is the subject of this position statement developed by the ANPA Committee on Research. The purposes of this position statement are to define neuropsychiatric research, describe the challenges currently facing neuropsychiatric clinician-scientists, note the opportunities for neuropsychiatric research and the training needed to take advantage of these opportunities, and make recommendations regarding how neuropsychiatric research can be fostered.

DEFINING NEUROPSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

Within biomedical research, two general types of investigation are distinguished: basic science and applied or clinical science. Basic science refers to studies that are laboratory based and do not directly include patients in the experimental design (such as molecular and cellular biology). Clinical or applied research is intended to elucidate human biology and disease and involves the participation of human beings.3,4 Five types of investigations within the domain of human clinical research have been defined3: 1) studies of the mechanisms of human disease, 2) studies of disease management, 3) epidemiology, 4) development of new technology, and 5) assessment of health care delivery.

Basic and applied research are not separated by firm boundaries. Some types of basic research use human tissues, and many basic research advances have clinical applications. Moreover, clinicians often make valuable observations that guide laboratory investigations leading to important discoveries. Neuropsychiatry is poised to translate basic science observations into clinical practice and to make clinical observations that can be further explored in the laboratory. This point of interchange between laboratory and clinic is the domain of the neuropsychiatric clinician-scientist and gives basic research its human value.

Human research is particularly complex, dealing with individuals who are ill and often in crisis. The needs of the patient must be served at the same time that data are collected and information is generated. Basic research usually can employ extensive controls, allowing the manipulation of a single variable and the emergence of firm conclusions. Human research, in contrast, is integrative; it cannot control all variables influencing the outcome of a study, and it must depend more on inference buttressed by observations made from multiple approaches to a single problem. Neuropsychiatric research is particularly challenging because the diseases involved affect the self—the patients' perceptions, memories, and judgments of their own illnesses. The neuropsychiatric clinician-scientist incurs the dual obligation of excellence in research and humane patient care.

Clinical science is undervalued and has no defined role in many academic organizations. The realization that the ideal of the “triple-threat” faculty (basic science researcher, teacher, clinician) was not feasible led to the development of the “two-platoon” model recognizing two groups within academics—one conducting basic science investigations and one taking responsibility for clinical care and instruction.5 More recently, the “three-platoon” model—basic researcher, clinician-researcher, clinician-educator—has been proposed, recognizing that clinical research is complex, requires specialized training, and makes important contributions to the growth of science and the health of the citizenry.6 This three-platoon model creates an appropriate academic framework for clinical neuropsychiatric research.

CHALLENGES CONFRONTING THE NEUROPSYCHIATRIC CLINICIAN-SCIENTIST

Funding for Neuropsychiatric Research

Clinical research is funded by the federal government (primarily the National Institutes of Health; NIH), state and local governments, patient revenues, industry, and private philanthropy. These mechanisms are currently undergoing substantial change, and funding for neuropsychiatric research is in jeopardy.

Federal Funding:

The NIH is the primary source for research funding in the United States and has the largest budget of any research agency in the world. NIH preferentially supports basic science research. Reviewing RO1 investigator-initiated grants funded in 1991 by the NIH, a committee of the Institute of Medicine found that 30% could be construed broadly as clinical research, but only 10% to 12% of the total number of grants actually involved human subjects.4 Thus, approximately 90% of NIH funding supports nonhuman research. This research priority places the goals of clinical research in neuropsychiatry at a funding disadvantage.

Even though mental illness affects 15% to 20% of the U.S. population,7 the three institutes that conduct neuropsychiatrically oriented research receive proportionately limited funding: the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) receives 6% of the NIH budget, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) receives 6%, and the National Institute on Aging (NIA) receives 4%. Within each of these institutes the amount of funding devoted to neuropsychiatry is very modest.

A recent survey conducted by the American Academy of Neurology8 revealed that 44% of clinical researchers in departments of neurology have federal support, compared with 82% of basic science researchers. Federal funds were the primary source of salary support for 58% of basic scientists and 16% of clinical researchers. Patient revenue constituted the primary salary support for 43% of clinical investigators and 7% of basic scientists. Thus, clinical researchers received less research support from federal sources, had less salary support from federal research grants, and relied more on patient-related income for their salaries. These allocations and requirements place clinician-scientists at greater risk from changes in the organization of health care that entail reductions in patient-based income.

Support for training of clinician-scientists by the NIH also lags behind that for basic scientists. Only 9% of the National Research Service Awards, one of the most popular governmental vehicles for funding the training of scientists, is devoted to behavioral sciences, while 59% support basic biomedical sciences.9

Academic Health Centers:

An academic health center is composed of a medical school, a teaching hospital, and at least one other health professional school, organized to achieve mutually agreed upon goals for education, research, and clinical care.9 Sixty-eight percent of NIH investigator-initiated research support (RO1 grant series) goes to academic health centers, and they are the major arenas of medical research and medical research training in the United States. They have typically received more than half of their income from a combination of federal sources and patient care. In 1992–1993, they received 47.4% of their income from medical care, 19.1% from federal research support, 11.7% from state and local agencies, and 21.8% from other sources.10

In the past, academic health centers used cost shifting to subsidize education and research;11 now, these institutions are under extraordinary pressure because income from all available sources is declining. Federal support for research is slated for reduction, and changes in health care delivery threaten patient-based income. Academic health centers must decrease costs to compete for patients with managed care organizations, and reimbursement levels from governmental payers (Medicare, Medicaid) are also declining. Decreased payment requires clinicians to engage in a compensatory increase in time devoted to patient care to maintain their salaries and reduces the proportion of time available for research.

Managed care organizations may also redirect patients away from academic health centers. Patients may be referred to other settings for care, and thus the patient populations that formed the basis for clinical research may no longer be available. Behavioral health care companies, for example, typically exclude academic psychiatrists (regarded as too expensive), reduce access by patients to academic health centers, and limit the availability of specialized mental health expertise (such as neuropsychiatry).12

Industry-Sponsored Research:

Industry-sponsored research in academic centers is also threatened. Patient populations necessary to conduct clinical trials are declining because of reorganization of health services delivery. Moreover, the cumbersome bureaucracies and slow institutional review boards of many universities make them less attractive than nonuniversity community research organizations that have lower indirect costs and more rapid response capabilities.13 In 1991, 35% of physician clinical investigators received corporate support for their research,14 and in a recent survey, 84% of neurologists favored having more industry sponsorship of academic research.11 Industry-sponsored research is an important activity of the clinician-scientist, and efforts to improve and foster university–industrial relationships are needed. As these relationships develop, institutional structures to oversee patent and royalty agreements and potential conflicts of interests may be required.

One school of thought contends that basic science is conducted by academicians in university settings, while applied research is conducted by industry.14,15 However, industry-sponsored research is concerned primarily with the development of new products, and many important clinical investigations do not have market value. For example, pharmaceutical companies conduct clinical trials to determine the efficacy of pharmacologic agents in idealized populations, but further clinical research is required to determine the effectiveness of these agents in patients with typical comorbid conditions and receiving multiple medications (patients usually excluded from clinical trials). Patients with psychiatric symptoms associated with neurologic disorders may have unique side effects and response profiles that require investigation and documentation. For instance, doses of antipsychotic agents in the levodopa-associated psychosis of Parkinson's disease differ from the doses of the same agents used in schizophrenia.16,17 Clinical research, including neuropsychiatric research, must be conducted by academic investigators and cannot be relegated entirely to industry.

Philanthropic Support for Research:

In 1991, 34% of physician clinical investigators received support from nonprofit organizations.14 Few organizations, however, specifically support neuropsychiatric research, and few researchers know how best to approach the appropriate organizations and individuals. More effort by neuropsychiatric clinician-scientists must be directed toward identifying potential donors and educating them about the importance of neuropsychiatric research.

Emphasis on Primary Care

The increasing emphasis on primary care places specialist-based clinical activities at a disadvantage. In addition, the training of future neuropsychiatric clinician-scientists is compromised. Managed care efforts to limit the use of specialists and federal initiatives intended to increase the number and proportion of primary care practitioners both contribute to the movement away from involvement of specialists, including neuropsychiatrists.

The goal of achieving cost savings by shifting from specialists to generalists may be elusive. Specialist care is regarded as more expensive than generalist care,18 but as generalists begin to use more advanced technologies and more complex therapies, generalist care of specific categories of patients will be no less expensive, and possibly more costly, than specialist care.19 The rapid advances in technology development make it impossible for the generalists to be conversant with these techniques in all areas of clinical medicine. Comprehensive initial assessment, although more expensive, may save total expenditures if effective therapy is implemented early and the costs of treatment failures are avoided. Expert care may reduce unnecessary testing and inappropriate treatment while achieving a more accurate diagnosis and identifying the most effective assessments and interventions. Health improvement per investment has been shown to be greater with specialist than generalist care for some disorders.20

Neuropsychiatric disorders are among the conditions that are likely to be more expensive when managed by generalists unfamiliar with the diagnostic technologies and complicated treatments required. A recent survey of community-dwelling elderly patients cared for by generalists found that 23% had received a prescription for at least one of 20 contraindicated drugs.21 A study of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) found that those who were managed by a primary care physician with no previous experience with AIDS died on average more than a year sooner than those whose physicians had treated at least five patients.22

Primary care practitioners value the advice of experts and seek collaboration with specialists in many circumstances. Clarfield et al.,23 for example, showed that the practice patterns of primary care practitioners were affected by participation in a consensus conference on the assessment of dementia. Consumers often seek care from specialists as well as generalists and value the availability of research opportunities in university settings. Connell and Gallant24 found that among the most common reasons for caregivers to seek care for their demented family members in a university-based clinic was participation in drug-related research. They also noted that lack of access to physicians trained to diagnose dementing illness was among the most common complaints of the caregivers. From a consumer point of view, greater collaboration between generalists and specialists would be advantageous.

Neuropsychiatrists can have an important role in assisting neurologists and psychiatrists as well as primary care practitioners. In a study of patients with epilepsy, mood changes had the highest correlation with and the greatest predictive value for quality of life (depression explained 47% of the variance).25 Thus, the neuropsychiatric dimension of epilepsy, which has received relatively little emphasis, is of greatest significance to patients' perceptions of their lives.

Training-Related Challenges

Several of the challenges facing the neuropsychiatric clinician-scientist are related to the required training. Substantial time is needed to accrue the necessary skills—medical school, internship, residency in psychiatry or neurology, or fellowship in neuropsychiatry. The prolonged training results in considerable accumulated debt. The choice to become a neuropsychiatric clinician-scientist will be made more difficult when compared with the shorter training requirements and rising reimbursement rates of the generalist. Increased funding of training programs through federal or philanthropic means will be required to ensure the future of the neuropsychiatric clinician-scientist.

The absence of certification for neuropsychiatry may also hinder recruitment of trainees into the specialty. The investment of time and the deferral of debt repayment and of salary may be less attractive when the credential achieved lacks national standards or recognition.

The absence of appropriate mentors is also a challenge in neuropsychiatry. A recent survey of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, an organization with goals and interests closely allied to those of neuropsychiatry, found that although the membership is academically oriented and 51% have done research for five or more years, 43% had no recent publications and 74% had fewer than 10 total publications.26 Mentoring and adequacy of research time are identified by clinical researchers as the two most important determinants of receipt of federal funding for their research, an important measure of success.14 A survey of the residency training directors in U.S. psychiatry programs revealed that a major reason for the absence of learning opportunities in the area of neuropsychiatry is the lack of neuropsychiatric faculty prepared to teach the information.27 Successful preparation of future neuropsychiatric clinician-scientists depends on developing a cadre of mentors who are themselves successful researchers and who are willing to devote time to teaching trainees.

Lack of appropriate training in grant preparation is partially responsible for the low rate of funding of clinical research proposals. A study by the Clinical Research Subcommittee of the Scientific Issues Committee of the American Academy of Neurology8 found that 66% of research proposals rejected by NIH review groups were judged to have poor methodology, 41% had inappropriate data collection, 40% lacked proper controls, and 31% had poor data analytic strategies. Thus, adequate training in neuropsychiatry must include instruction on the preparation of grant proposals.

Neuropsychiatric research must also be introduced much earlier in the medical school curriculum; a recent survey of 30 academic health centers found that none provided an introduction to clinical research for medical students.28

Outcomes Assessment and Cost-Utility of Neuropsychiatric Care

To survive and flourish in an era of managed care, neuropsychiatry must show that it can improve the quality of care and can do so within a defined cost-utility framework.29 Advances in quality of care and cost savings from successful neuropsychiatric interventions are difficult to quantify, but their measurement must be part of the neuropsychiatric research agenda. Several recently introduced therapies have been shown to produce cost savings in the course of patient care. Interferon beta-1b therapy for multiple sclerosis, although expensive, reduced hospitalization rates and costs among patients with relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis.30 Similarly, patients with Alzheimer's disease who received treatment with tacrine, vitamin E, or selegiline had a significant delay in nursing home placement, with associated cost savings.31,32 These examples demonstrate that appropriate treatment of neuropsychiatric illnesses can result in reduced health care expenditures. More such research is needed to further support the utility of neuropsychiatric research and care.

Training for Neuropsychiatric Clinician-Scientists

The training of neuropsychiatric clinician-scientists must provide the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to succeed in clinical research devoted to neuropsychiatric issues. Clinical research requires the same didactic exposure, mentorship, and experience as laboratory science. Currently, many fellowships for clinical research tend to emphasize additional diagnostic skills; trainees need to learn epidemiology, biostatistics, health services research, bioethics, and health economics.33 Neuropsychiatric fellowships should provide clinical instruction to achieve excellence in clinical care, balanced with research instruction and experience that will prepare the trainee for the rigors of clinical research.

OPPORTUNITIES IN NEUROPSYCHIATRIC CLINICAL RESEARCH

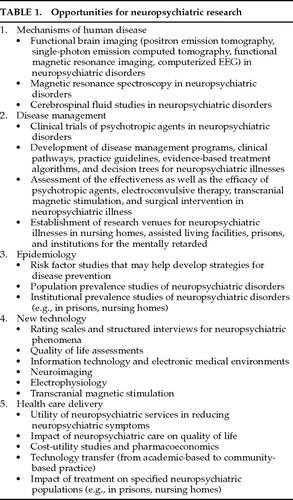

Despite the challenges to neuropsychiatric research described above, the opportunities for such research are great. Table 1 lists the five major types of clinical research3 as they apply to neuropsychiatry and provides examples of research topics of current interest.

Several categories of research are particularly suited to neuropsychiatric investigation. One is research in the treatment of special populations. Attention deficit syndrome in children, poststroke depression, psychosis in Alzheimer's disease, and apathy in neurologic disorders are examples of common problems with populations sufficiently large to be of interest to pharmaceutical companies. Drug responses in these specific populations and interactions with other drugs commonly used in patients with these diseases require study to allow optimal psychotropic drug use.

Application of new neuroimaging technologies is another area that lends itself to neuropsychiatric research. The utility of positron emission tomography, single-photon emission computed tomography, functional magnetic resonance imaging, and magnetic resonance spectroscopy in disease diagnosis and monitoring of therapy have yet to be defined in many neuropsychiatric patient populations.

Outcomes research is a fertile area for neuropsychiatric research and one of great potential benefit to neuropsychiatrists.29 Data regarding the effectiveness of current diagnostic approaches and therapeutic interventions are urgently needed. In addition, assessment of the utility of new therapies and tests that have been widely adopted by community practitioners is also required.

The advent of managed care also has created new opportunities. Some behavioral health companies prefer to identify specific patient populations requiring substantial specialty consultation and provide “carve-out” contracts to academic or specialty groups, bypassing the primary care practitioner. Neuropsychiatric clinician-scientists can use these arrangements to maintain patient flow and ensure the availability of research populations while providing excellent care. Information systems in managed care organizations are typically well developed and can serve the clinician-scientist with access to them.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Preamble

Science is essential to national and global welfare and can help solve many of the most pressing problems of the nation and the world. Applied science honors the implied covenant between scientist and taxpayer or donor that research will relate to the improvement of the lives of patients. Neuropsychiatric research is relevant to some of the most fundamental problems facing societies, including mental illness, brain disease in old age, behavioral effects of acquired brain disorders, childhood illnesses, and violence. Neuropsychiatric research can translate basic science advances into improved clinical care and can stimulate and provide a focus for basic science investigations. Neuropsychiatric research can produce major economic benefits through the early identification, proper assessment, and appropriate treatment of complex and costly disorders. Neuropsychiatric research can also produce substantial human benefit in terms of reduced suffering, improved quality of life, and increased actualization of human potential. Support of clinical research represents an investment in the future care of patients. The following recommendations are made to enhance the ability of the neuropsychiatric clinician-scientist to perform research.

Funding Neuropsychiatric Research

| • | Neuropsychiatric research depends on funding, and public and private funding providers must be educated regarding the magnitude of neuropsychiatric disability in the population and the important contributions to be made by neuropsychiatric research. | ||||

| • | Within the NIH, greater effort should be devoted to composing review panels with members experienced in clinical neuropsychiatric research. | ||||

| • | Neuropsychiatric illnesses are major challenges to the health of elderly citizens, and Medicare will benefit from advances in neuropsychiatric research. Medicare should fund neuropsychiatric research and training. | ||||

| • | Likewise, managed care companies and insurance companies also benefit from advances in neuropsychiatric research and should provide specified amounts of funding or be taxed to support research and research training. | ||||

Academic Health Centers

| • | Neuropsychiatrists make important contributions to the functioning of academic health centers in terms of attracting patients and providing services. Academic health centers should reward clinician-scientists for their accomplishments with promotion, tenure, and support similar to the benefits extended to basic scientists. | ||||

| • | Academic health centers should develop strategic alliances with other organizations, such as pharmaceutical companies, that will be useful in facilitating clinical research and as part of a health care network that includes research and teaching. | ||||

| • | Academic bureaucracies should be simplified and streamlined to facilitate interactions between academic researchers and industry. | ||||

| • | Similarly, academic health centers should simplify and streamline institutional review processes, without compromising patient safety, to enhance the ability of academically based researchers to compete with private sector research organizations conducting clinical trials. | ||||

| • | Academic health centers should actively support the interdisciplinary research required for contemporary advances in neuropsychiatry. Traditional disciplinary boundaries between neurology, psychiatry, neuropsychology, and neuroscience are inimical to the success of an interdisciplinary enterprise. In addition, the bidirectional flow of information between basic and applied science requires creative administrative formulations and active institutional support.34 Collaboration among academic health centers may also create new opportunities to facilitate research and provide integrated patient care. | ||||

| • | Academic health centers may enhance their own survival and help ensure the availability of a sufficient number of patients for clinical research by forming academic managed care networks35 and by developing carve-outs of selected patient groups from managed care companies to neuropsychiatric clinician-scientists. | ||||

Industry-Sponsored Research

| • | Pharmaceutical companies and other industry sponsors of research must be informed about the advantages of including academic health centers in clinical trials and other assessments of treatments and technologies. These advantages include expert faculty who can contribute to research design and analysis, availability of more severely ill populations, motivation to explore new arenas for drug application, and the ability to perform important “add-on” research such as pharmacokinetic analyses, neuroimaging, or outcome assessments. In addition, practitioners in academic health centers are rarely entirely dependent on industry support for income, and they are motivated to make academic contributions beyond participating in clinical trials. Thus, they are more independent of financial conflict of interest than community-based research organizations, and they are more likely to pursue accurate diagnosis, elimination of patients with complicating conditions, and identification of adverse events. | ||||

| • | Industry should also be encouraged to support research training, not least because industry draws on the pool of academically trained clinician-scientists to direct its clinical trials and related programs. | ||||

Neuropsychiatric Training and Credentialing

| • | The need for neuropsychiatric practitioners will expand as the population ages, and further advances in neuroscience will demand the availability of clinicians familiar with new tools and agents. Training for research in neuropsychiatry must be championed in Congress as well as in federal funding agencies including the NIH and Medicare. | ||||

| • | Contributions from managed care should be partially directed to the support of neuropsychiatric research training. | ||||

| • | More federal funding for training programs is needed and should reflect the special requirements of the neuropsychiatric clinician-scientist. | ||||

| • | Neuropsychiatric fellowship programs devoted to producing clinician-scientists should include teaching of research design, clinical trials, biostatistics, grant writing, bioethics, publication, and academic promotion to prepare trainees for successful research careers in academic settings. | ||||

| • | Debt-forgiveness programs that encourage residents to enter clinical research careers by decreasing their federal debt repayment requirements in return for time spent in research training and performing research should be created and extended to neuropsychiatry trainees. | ||||

| • | Federal stipends for fellows should be increased to reflect the postresidency status of fellows. | ||||

| • | Grant portability, allowing trainees to study with several different mentors during the funded period, might enhance the attractiveness of neuropsychiatric training. | ||||

| • | Mentoring relationships with trainees must be fostered, and faculty time devoted to fellows should be funded as part of fellowship awards. | ||||

| • | Recognition of specialized expertise through the granting of a certificate of added qualification is recommended. | ||||

| • | Exposure to neuropsychiatry and neuropsychiatric research should occur early in medical school and continue throughout residency to encourage the entry of students into the field and to enhance the sophistication of all practitioners. | ||||

Managed Care and Neuropsychiatric Practice

| • | The availability of neuropsychiatrists in managed care settings may reduce costs, improve patient care, and enhance competitiveness in the managed care market. Health care delivery systems should be structured to allow access to neuropsychiatrists by patients and by generalists or other specialists requesting neuropsychiatric assistance. | ||||

| • | Neuropsychiatrists can aid generalists by developing practice guidelines and care pathways that define appropriate assessment and treatment. | ||||

| • | Outcomes research demonstrating the cost-utility of neuropsychiatric care must be undertaken, and the data must be used to make evidenced-based recommendations to managed care organizations regarding the advantages of neuropsychiatric services. | ||||

Public Sector Collaboration

| • | The neuropsychiatric clinician-scientist has an obligation to participate in public education that will lead to accurate perceptions of what is available from neuropsychiatry. The public may have unrealistically high expectations of science, assuming that all diseases are now readily diagnosed and treated with advances in technology and therapy, or they may have unrealistically low expectations, believing that there is little to be done for diseases such as Alzheimer's disease that until recently had no treatments available. | ||||

Advocacy for Neuropsychiatry

| • | The recommendations made here will not produce change without proactive advocacy by neuropsychiatrists and their allies. Necessary activities include lobbying those in decision-making positions, educating the public about neuropsychiatry, informing generalists and other specialists about neuropsychiatry, and conducting outcomes research that establishes the importance of neuropsychiatric assessments and interventions. | ||||

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Neuropsychiatric research has much to contribute to the health of the nation and the world. Recent progress has been made in treating degenerative and demyelinating disorders, depression, psychosis, mania, and epilepsy. These advances, however, have ameliorated only a small part of the morbidity and mortality of neuropsychiatric illness, and the march of progress must be maintained. Support for this area must not falter in the changing research environment, and new means of expanding research support and attracting able trainees while providing them with the tools to advance neuropsychiatric research must be found.

|

1. Cummings JL, Hegarty A: Neurology, psychiatry, and neuropsychiatry. Neurology 1994; 44:209–213Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Green RC, Benjamin S, Cummings JL: Fellowship programs in behavioral neurology. Neurology 1995; 45:412–415Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ahrens EH Jr: The Crisis in Clinical Research. New York, Oxford University Press, 1992Google Scholar

4. Committee on Addressing Career Paths for Clinical Research: Careers in Clinical Research. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1994Google Scholar

5. Petersdorf RG: The evolution of departments of medicine. N Engl J Med 1980; 303:489–496Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Spencer SS: Careers in academic neurology, 1996. Ann Neurol 1996; 40:123–127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Burke JD, Regier DA: Epidemiology of mental disorders, in The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Psychiatry, 2nd edition, edited by Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 81–104Google Scholar

8. Clinical Research Subcommittee of the Scientific Issues Committee of the American Academy of Neurology: Status of clinical research in neurology. Neurology 1995; 45:839–845Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Committee on National Needs for Biomedical and Behavioral Research Personnel. National Research Council. Washington, DC, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1994Google Scholar

10. Steinberg J: NIH panel plans to give clinical research a hand. Journal of NIH Research 1995; 7:34–36Google Scholar

11. Ringel SP, Vickery BG, Rogstad TL: US neurologists: attitudes on the US health care system. Neurology 1996; 47:279–287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Iglehart JK: Managed care and mental health. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:131–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Griffin JW, Griggs RC, Barchi R, et al, and the Working Groups of the Long Range Planning Committee: Opportunities and challenges in academic neurology: report of the Long Range Planning Committee of the American Neurological Association. Ann Neurol 1996; 39:693–699Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Lee TH, Ognibene FP, Schwartz JS: Correlates of external research support among respondents to the 1990 American Federation for Clinical Research Survey. Clin Res 1991; 39:135–144Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bloom FE: A Paine-ful start (editorial). Science 1995; 269:459Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Pickar D: Prospects for pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Lancet 1995; 345:557–562Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Pfeiffer RF, Kang J, Graber B, et al: Clozapine for psychosis in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 1990; 5:239–242Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Zubkoff M, et al: Variations in resource utilization among medical specialties and systems of care: results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA 1992; 267:1624–1630Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Crump BJ, Panton R, Drummond MF, et al: Transferring the costs of expensive treatments from secondary to primary care. Br Med J 1995; 310:509–512Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Sturm R, Wells KB: How can care for depression be more cost effective? JAMA 1995; 273:51–58Google Scholar

21. Wilcox SM, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S: Inappropriate drug prescribing for the community-dwelling elderly. JAMA 1994; 272:292–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Stephanson J: Survival of patients with AIDS depends on physicians' experience treating the disease. JAMA 1996; 275:745–746Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Clarfield AM, Kogan S, Bergman H, et al: Do consensus conferences influence their participants? Can Med Assoc J 1996; 154:331–336Google Scholar

24. Connell CM, Gallant MP: Spouse caregiver's attitudes toward obtaining a diagnosis of a dementing illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996; 44:1003–1009Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Perrine K, Hermann BP, Meador KJ, et al: The relationship of neuropsychological functioning to quality of life in epilepsy. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:997–1003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Jeste DV, Fitten LJ, Clemons B, et al: A survey of geriatric psychiatrists in the US regarding research. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1993; 8:13–18Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Duffy JD, Camlin H: Neuropsychiatric training in American psychiatric residency training programs. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 7:290–294Link, Google Scholar

28. Gallin JI, Smits HL: Managing the interface between medical schools, hospitals, and clinical research. JAMA 1997; 277:651–654Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Coffey CE, Cummings JL, Duffy JD, et al: Assessment of treatment outcomes in neuropsychiatry: a report from the Committee on Research of the American Neuropsychiatric Association. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 7:287–289Link, Google Scholar

30. IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group: Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, I: clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 1993; 43:655–661Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Knopman D, Schneider L, Davis K, et al, and the Tacrine Study Group: Long-term tacrine (Cognex) treatment: effects on nursing home placement and mortality. Neurology 1996; 47:166–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, et al, and the Alzheimer's Cooperative Study: A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopheral, or both as treatment for Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:1216–1222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Whisnant JP: Whither clinical research? Neurology 1995; 45:607–608Google Scholar

34. Wyngaarden JB: The future of clinical investigation. Cleveland Clin Q 1984; 51:567–574Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Rogers MC, Synderman R, Rogers EL: Cultural and organizational implications of academic managed-care networks. N Engl J Med 1994; 331:1374–1377Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar