Clozapine and Risperidone Treatment of Psychosis in Parkinson's Disease

Abstract

The authors compared efficacy and safety of risperidone and clozapine for the treatment of psychosis in a double-blind trial with 10 subjects with Parkinson's disease (PD) and psychosis. Mean improvement in the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale psychosis score was similar in the clozapine and the risperidone groups (P=0.23). Although the mean motor Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale score worsened in the risperidone group and improved in the clozapine group, this difference did not reach statistical significance. One subject on clozapine developed neutropenia. In subjects with PD, risperidone may be considered as an alternative to clozapine because it is as effective for the treatment of psychoses without the hematologic, antimuscarinic, and seizure side effects. However, risperidone may worsen extrapyramidal symptoms more than clozapine and therefore must be used with caution.

Psychotic symptoms occur in approximately 30% of patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) treated with dopaminergic medication.1 These symptoms include hallucinations, delirium, confusion, and disorientation. The exact cause of the psychosis is unclear, but antiparkinsonian medications are implicated because psychosis rarely occurs in unmedicated patients with PD. In addition, hypersensitivity of postsynaptic dopamine receptors and/or overstimulation of the mesolimbic dopamine and serotonergic receptors may also contribute to the development of psychosis.2 The psychotic symptoms are often difficult to treat because of a pharmacologic dilemma. Reduction of the antiparkinsonian medication doses may successfully diminish psychoses but generally worsens parkinsonian motor symptoms. Typical neuroleptic agents may also ameliorate the psychosis but often worsen the parkinsonian motor symptoms as well.

Several studies suggest that the atypical neuroleptic clozapine is effective in treating psychosis in both schizophrenia3–5 and PD6–13 without exacerbating motor symptoms. In fact, clozapine may actually improve some aspects of PD, such as tremor and dyskinesias.11,12,14–16 (The dose of clozapine used in the PD studies ranged from 6.25 to 150 mg/day.) Despite these benefits, side effects prompt caution in prescribing clozapine. Common side effects that often interfere with therapy include sedation, confusion, sialorrhea, seizures, and hypotension.4 The most serious potential effect is agranulocytosis, which occurs at a cumulative incidence at one year of about 1.3%. For this reason, the white blood cell (WBC) count must be monitored on a weekly basis. Because of these common and potentially serious side effects, there is considerable interest in finding an agent with similar efficacy but fewer side effects.

Risperidone, a benzisoxazole derivative, is another antipsychotic agent. The efficacy of risperidone for psychosis in subjects with schizophrenia has been established,17–20 with the maximal effect seen with doses between 4 and 6 mg/day. Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) were similar to placebo at doses less than or equal to 6 mg/day. Results using risperidone to treat psychoses in subjects with PD are mixed. Some studies report risperidone to be effective and safe in treating psychoses, without worsening of EPS,21,22 whereas other studies report risperidone to be less effective than other atypical neuroleptics, with worsening of EPS.23,24

To determine whether risperidone is better tolerated and as effective as clozapine for the treatment of psychosis in PD, we conducted a single-center, randomized double-blind comparison trial of clozapine and risperidone in subjects with PD and psychosis.

METHODS

Patient Selection Criteria

All subjects were recruited, using a consecutive sampling process, from the Movement Disorders Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital. Entry criteria included men and women with a clinical diagnosis of idiopathic PD. All participants had levodopa-exacerbated psychosis not satisfactorily managed by levodopa dose reduction and were able to give informed consent. Exclusion criteria were other major concurrent illnesses; a primary DSM-IV psychiatric diagnosis including schizophrenia or metabolic psychosis; a history of epilepsy; a prior bone marrow disorder or leukopenia; taking medications toxic to the bone marrow or experimental treatments in the past 6 weeks; using antipsychotic neuroleptic agents within the past 6 months; pregnancy; and childbearing potential in women not using adequate contraception.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the psychosis cluster subset of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).25 The BPRS is a multi-item inventory of general psychopathology used to evaluate the effects of drug treatment in psychosis. It consists of 18 symptom and behavior groups that span the range of psychiatric manifestations. Each symptom group is scored on a 1–7 scale with 1 representing “not present” and 7 representing “extremely severe.” The maximum score is 126. Clinical scoring is based on information obtained in an interview session. The BPRS psychosis cluster includes conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, suspiciousness, unusual thought content, and hostility. The maximum score is 35. We chose the psychosis cluster subset of the BPRS because of its documented high interrater reliability, proven validity, and extensive use in psychopharmacological research.25,26 The BPRS was successfully used as a measure of efficacy in several clinical trials of clozapine in subjects with PD1,2,6–9,11,27 and in one study of risperidone in subjects with PD.24

Secondary outcome measures included the motor section of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) and a quantitative electrophysiologic test of tremor. The UPDRS has been administered in several large clinical trials in PD and is a highly reproducible and validated measure of motor function in PD.28 The total score ranges from 0 to 108 (normal function to severe dysfunction). Tremor at the wrist was measured by using a portable, noninvasive apparatus with two solid-state accelerometers that record frequency and amplitude.29

General Study Design

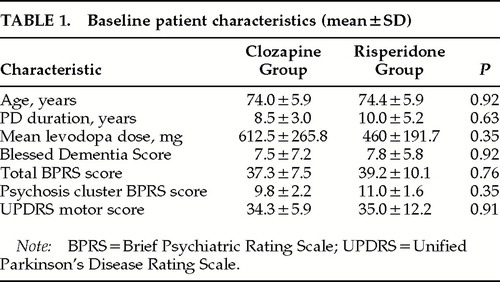

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Massachusetts General Hospital. All subjects signed an informed consent document. Ten subjects with Parkinson's disease and psychosis were enrolled and randomized to risperidone (n=5) or clozapine (n=5) treatment. The medications were dispensed in weekly packages. Clozapine was started at 12.5 mg at bedtime. The dose was increased gradually by 12.5 to 25 mg every week for 1 month until symptomatic improvement was achieved or intolerable side effects emerged. Risperidone was started at 0.5 mg/day and gradually increased by 0.5 mg/day every week for 1 month until symptomatic improvement was achieved or intolerable side effects emerged. The total daily dose for both clozapine and risperidone was taken half in the morning and half at bedtime. The medications were stopped if the WBC fell below 3,000/mm3. All other anti-PD medications were held constant throughout the duration of the trial. Subjects in the two groups did not differ in baseline clinical characteristics (Table 1): age, duration of PD, Hoehn-Yahr stage,30 duration of psychosis, duration of levodopa therapy, levodopa dose, other medications, and the Blessed Dementia Score (BDS).31

Each subject received drug for 3 months and was assessed prior to initiation of treatment and after 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment. All primary and secondary outcome measures were obtained at each visit. Electrolytes and liver function tests (LFTs) were measured at the beginning and end of treatment. Complete blood cell (CBC) counts were monitored weekly in all patients throughout the study. Motor tests were administered to subjects when they were in an “on” (symptomatic) state. For subjects taking regular carbidopa/levodopa (Sinemet), the motor tests were administered between 1 and 2 hours after the last levodopa dose. For subjects taking Sinemet CR (the sustained-release form), motor tests were administered between 3 and 4 hours after the last dose.

A blinded investigator administered all primary and secondary outcome measures. A second, unblinded investigator managed medication dosage, checked WBC counts, and monitored for adverse effects. At each visit, the unblinded investigator performed physical and neurological examinations and monitored subjects for side effects by means of an open questionnaire and side effects checklist.

Safety and Compliance Assessment

Safety was determined by clinical history and examination, recording of adverse events, and a panel of blood and urine safety laboratory tests (CBC, electrolytes, and LFTs). Compliance with study drug dosing was determined by reviewing diaries at each visit and by counting returned capsules.

Statistical Methods

With 10 subjects, there was an 80% chance to detect a 50% difference in the mean change in BPRS score between treatment groups at a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05. This probability is based on the assumption that the standard deviation of the difference is 2.0.

A UNIX-based SAS program (SAS, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for descriptive statistics and significance testing.32 Mean age, duration of PD, duration of levodopa treatment, male-to-female ratio, proportion of subjects on other PD medications, and mean BPRS and BDS scores were determined for both treatment groups. Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical data and the Wilcoxon rank sum test to compare continuous data. The mean dose of clozapine or risperidone was calculated for each group.

Within-group and between-group comparisons of the outcome measures were performed by using two-sided nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon rank sign test or Wilcoxon rank sum test). The pre–post-treatment change in BPRS, UPDRS, and tremor (frequency and amplitude) were calculated by using the baseline and 3-month evaluation scores. The last on-drug score was used for subjects who terminated the study prior to the 3-month visit.

RESULTS

Patient Population

Of the 10 subjects enrolled in the study, 5 were randomized to the clozapine group and 5 to the risperidone group; there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups (Table 1). All subjects received Sinemet or Sinemet CR. Only one subject took selegiline (Eldepryl). None of the subjects received anticholinergic medication or other symptomatic treatments for PD.

Safety and Compliance

One subject in the clozapine treatment group developed a bowel infarction after baseline testing and randomization but prior to initiating drug treatment. Compliance with the study drug dosing regimen was 100% for the remaining 9 subjects. The mean clozapine dose was 62.5±32.7 mg/day (mean±SD reported throughout), with a range from 25 mg/day to 100 mg/day. The mean risperidone dose was 1.2±0.3 mg/day, with a range from 1 to 1.5 mg/day. Three subjects terminated the study early. The WBC count dropped below 3,000/mm3 after 10 weeks of treatment in one subject receiving clozapine but increased to 5,000 after stopping clozapine. Another subject receiving clozapine experienced marked increase in rigidity and incontinence of urine after 4 weeks of treatment. One subject taking risperidone developed increased rigidity and urinary incontinence after 8 weeks of treatment. All three adverse events resolved with cessation of study medication. The rigidity was present in the latter 2 subjects only while they were on study medication. No clinically significant changes were noted in vital signs or chemistry laboratory tests with either treatment.

Outcome Measures

Data from 4 subjects on clozapine and 5 on risperidone were used for the analyses of all outcome measures.

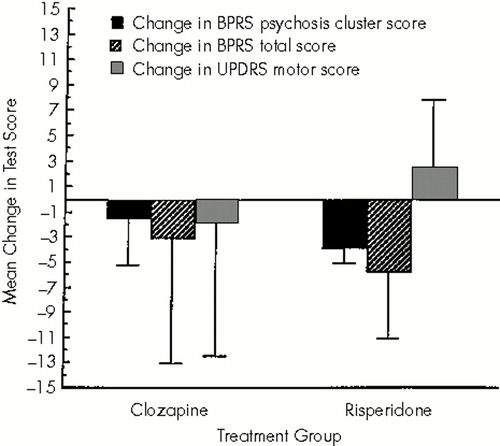

The mean BPRS psychosis cluster score improved significantly with treatment in the risperidone group (P=0.004), but not in the clozapine group (P=0.32). The mean improvement in the BPRS psychosis score was 1.5±3.7 with clozapine and 3.8±1.3 with risperidone (Figure 1). However, there was no statistically significant between-group difference in efficacy (P=0.23). One subject in each treatment group had no change in the psychosis cluster BPRS score.

The mean improvement in the total BPRS score was not statistically significant compared with the baseline scores in either group and was not different between treatment groups. The mean improvement in the total BPRS score was 3.0±10.0 with clozapine and 6.0±4.6 with risperidone treatment (between-group comparison, P=0.57).

The UPDRS motor score improved 1.8±10.6 points in the clozapine group and worsened 2.4±4.6 in the risperidone group (between-group comparison, P=0.45). This change was not significant within either group. The UPDRS motor score worsened in 1 subject in the clozapine group and in 3 subjects in the risperidone group. There was no change in the tremor frequency or amplitude in either treatment group (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Treatment of psychosis in our subjects with PD using either clozapine or risperidone resulted in improvement in both the psychosis cluster and total BPRS scores, although improvement reached statistical significance in the psychosis cluster score in the risperidone group only. However, we did not find any statistically significant difference in efficacy between clozapine and risperidone. These results are consistent with prior studies that have demonstrated that clozapine and risperidone are effective in reducing psychosis in PD.6–13,21,22 In these previous studies, the dose of clozapine ranged from 6.25 to 150 mg/day and the dose of risperidone ranged from 0.25 to 1.5 mg/day. In our study, the dose of clozapine ranged from 25 to 100 mg/day and the risperidone dose was between 1 and 1.5 mg/day. Our failure to detect a difference in efficacy between risperidone and clozapine may be the result of the small sample size that permitted only the detection of a 50% or greater difference between the two treatments.

Our results are consistent with other studies regarding the safety of clozapine6–13 and risperidone.21,22 In a retrospective study of 172 subjects with PD who were treated with clozapine, 23% discontinued the medication because of side effects. Approximately 5% of their subjects developed worsening parkinsonism.13 Neutropenia occurs in approximately 1% of subjects taking clozapine. In a prior study of risperidone in subjects with PD, all subjects had worsening of their extrapyramidal symptoms at an average daily dose of 1.5 mg.24 In another open-label study of risperidone in subjects with PD, none of the 10 subjects treated for an average of 34.8 weeks developed extrapyramidal symptoms (mean dose 0.73 mg/day).22 Both drugs were well tolerated by the majority of our subjects, although 3 subjects experienced adverse events severe enough to warrant drug termination. There were no clinically significant changes in vital signs or chemistry laboratory tests after 3 months of treatment. One subject in each group experienced worsening of extrapyramidal signs, and 1 subject on clozapine developed neutropenia. Although the mean motor UPDRS score worsened in the risperidone group and improved in the clozapine group, this difference did not reach statistical significance.

We did not find any change in tremor characteristics (frequency and amplitude) in our subjects with PD with either clozapine or risperidone treatment. Tremor has been reported in several studies to improve in some subjects with clozapine treatment.11,12,14–16 In these studies, tremor improved at clozapine doses between 25 and 100 mg/day. The mechanism of action of clozapine on tremor is unknown. The majority of these studies were based on qualitative observations of tremor improvement. We failed to detect an improvement in tremor, using quantitative measures of tremor amplitude and frequency rather than a rating scale. Because of our small sample size, it is possible either that our subjects fell into the category of PD patients whose tremor is unresponsive to clozapine or that the study lacked the power to detect a small improvement in tremor.

Risperidone may be a reasonable alternative to clozapine in the treatment of psychosis in subjects with PD. Risperidone lacks the hematologic and antimuscarinic side effects associated with clozapine. It has not been associated with seizures. At doses less than 6 mg/day, risperidone does not cause more EPS symptoms than placebo in persons with schizophrenia. This profile may be due to the predominance of serotonin antagonism at low doses, along with more gradual dopamine D2 receptor occupancy when compared with typical neuroleptics, modulation of the dopamine system by serotonin 5-HT2 antagonism, and preferential blockade of mesolimbic rather than striatal dopamine receptors.22 However, our preliminary data suggest that risperidone may worsen extrapyramidal symptoms more than clozapine and therefore must be used with caution in individuals with PD.

Two other atypical neuroleptics have been discussed as effective alternatives in treating psychosis in subjects with PD. Olanzapine has been found to treat psychosis without worsening of EPS and without requiring blood monitoring.33 A more recent open-label trial reported that use of quetiapine in the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in subjects with Parkinson's disease resulted in a significant decrease in psychosis without a decline in motor function.34 Both olanzapine and quetiapine have a comparable pharmacologic profile to that of clozapine but without the hematologic and antimuscarinic side effects. They display antagonistic effects at the serotonergic (5-HT2A) and, to a lesser extent, dopaminergic (D2) receptors.35 Further studies investigating the efficacy of these atypical neuroleptics in treating psychosis in subjects with PD are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the patients and their families for their assistance with this project. M.E.C. is the recipient of National Institutes of Health Grant K08-NS01896 and the American Academy of Neurology Clinical Investigator Award.

FIGURE 1. Mean change in Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) psychosis cluster score, BPRS total score, and Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor score with clozapine or risperidone treatmentError bars show the standard deviation.

|

1 Wagner M, Defilippi J, Menza M, et al: Clozapine for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's disease: chart review of 49 patients. J Neuropsychiatry 1996; 3:276–280Google Scholar

2 Ostergaard K, Dupont E: Clozapine treatment of drug-induced psychotic symptoms in late stages of Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 1988; 78:349–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry1988; 45:789–96Google Scholar

4 Update on clozapine. Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics 1993; 35:16–18Medline, Google Scholar

5 Breir AF, Malhotra AK, Su TP, et al: Clozapine and risperidone in chronic schizophrenia: effects on symptoms, parkinsonian side effects, and neuroendocrine response. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:294–298Medline, Google Scholar

6 Friedman J, Lannon M: Clozapine in the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1990; 39:1219–1221Google Scholar

7 Kahn N, Freeman A, Juncos J, et al: Clozapine is beneficial for psychosis in Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1991; 41:1699–1700Google Scholar

8 Wolk S, Douglas C: Clozapine treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's disease: a report of five consecutive cases. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53:373–376Medline, Google Scholar

9 Scholtz E, Dichgans J: Treatment of drug-induced exogenous psychosis in parkinsonism with clozapine and fluperlapine. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1985; 235:60–64Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Factor S, Brown D: Clozapine prevents recurrence of psychosis in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 1992; 7:125–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 The Parkinson Study Group: Low-dose clozapine for the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:757–763Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Factor S, Brown D, Molho E, et al: Clozapine: a 2-year open trial in Parkinson's disease patients with psychosis. Neurology 1994; 44:544–546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Trosch R, Friedman J, Lannon M, et al: Clozapine use in Parkinson's disease: a retrospective analysis of a large multicentered clinical experience. Mov Disord 1998; 13:377–382Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Pakkenberg H, Pakkenberg B: Clozapine in the treatment of tremor. Acta Neurol Scand 1986; 73:295–297Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Friedman J, Lannon M: Clozapine treatment of tremor in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 1990; 5:225–229Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Jansen E: Clozapine in the treatment of tremor in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 1994; 89:262–265Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Claus A, Bollen J, DeCuyper H, et al: Risperidone versus haloperidol in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic inpatients: a multicentre double-blind comparative study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:295–305Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Borison R, Pathiraja A, Diamond B, et al: Risperidone: clinical safety and efficacy in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull 1992; 28:213–218Medline, Google Scholar

19 Chouinard G, Arnott W: Clinical review of risperidone. Can J Psychiatry 1993; 38(suppl 3):S89–S95Google Scholar

20 Chouinard G, Jones B, Remington G, et al: A Canadian multicenter placebo-controlled study of fixed doses of risperidone and haloperidol in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:25–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Workman RH Jr, Orengo CA, Bakey AA, et al: The use of risperidone for psychosis and agitation in demented patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 9:594–597Link, Google Scholar

22 Meco G, Alessandri A, Guistini P, et al: Risperidone in levodopa-induced psychosis in advanced Parkinson's disease: an open-label, long-term study. Mov Disord 1997; 12:610–612Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Rich SS, Friedman JH, Ott BR: Risperidone versus clozapine in the treatment of psychosis in six patients with Parkinson's disease and other akinetic-rigid syndromes. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:556–559Medline, Google Scholar

24 Ford B, Cote L, Fahn S: Risperidone in Parkinson's disease (letter). Lancet 1994; 344:681Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Overall J, Gorham D: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Bell M, Milstein R, Beam-Goulet J, et al: The positive and negative syndrome scale and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: reliability, comparability and predictive validity. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:723–728Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Lew M, Waters C: Clozapine treatment of Parkinsonism with psychosis. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993; 41:669–671Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Fahn S, Elton R: Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, in Recent Developments in Parkinson's Disease, vol 2, edited by Fahn S, Marsden C, Goldstein M, et al. New York, Macmillan, 1987, pp 153–163Google Scholar

29 Ghika J, Wiegner A, Fang J, et al: Portable system for quantifying motor abnormalities in Parkinson's disease. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1993; 40:276–283Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Hoehn M, Yahr M: Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 1967; 17:427–442Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Cole M: Interrater reliability of the Blessed Dementia Scale. Can J Psychiatry 1990; 35:328–330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 SAS Institute, Inc.: SAS/STAT Users Guide, version 6, 4th edition, vol 2, 1989Google Scholar

33 Wolters E, Jansen E, Tuynman-Qua H, et al: Olanzapine in the treatment of dopaminomimetic psychosis in patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1996; 47:1085–1087Google Scholar

34 Fernandez H, Friedman J, Jacques C, et al: Quetiapine for the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 1999; 14:484–487Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Wolters E: Dopaminomimetic psychosis in Parkinson's disease patients: diagnosis and treatment. Neurology 1999; 52(suppl 3):S10–S13Google Scholar