Psychotropic Medication Use in Patients With Epilepsy

Abstract

Physicians are often reluctant to use psychotropic medications in epilepsy patients with psychiatric disorders because of concern over the potential risk for lowering seizure threshold. This study assesses retrospectively the impact of psychotropic medications on seizure frequency in 57 patients seen consecutively at an epilepsy center. During psychotropic drug therapy, seizure frequency decreased in 33% of patients, was unchanged in 44%, and increased in 23%. Mean seizure frequency was not statistically different between pre-treatment and treatment periods (t=0.23, df=56). Simultaneous adjustments in antiepileptic drug regimen could not account for the findings. Results support the position that psychotropic medications, introduced slowly in low to moderate doses, can be safely used in epilepsy patients with comorbid psychiatric pathology during the regular course of clinical care.

Psychiatric disorders occur more frequently in patients with epilepsy than in the general population.1–4 The question of whether or not to use psychotropic medications for people with epilepsy thus arises frequently in clinical practice. Many patients can benefit from such treatment; the rates of morbidity and mortality in these psychiatric disorders are high. People with epilepsy, particularly those with temporal lobe foci, are at heightened risk for serious psychiatric complications, including suicide.5–8

Despite the clinical need, many physicians are reluctant to prescribe psychotropic medications to epilepsy patients because many of these drugs can lower the seizure threshold.9–13 In addition to the epileptogenicity of a given psychotropic medication, many other factors influence seizure threshold, including dose, rate of upward titration, and sudden drug withdrawal.14–17 The extent to which epilepsy is a relative contraindication for psychotropic medication use is uncertain and may depend on individual patient and medication factors.

In one of the few studies on the subject, Ojemann et al.18 found that psychotropics did not appear to affect seizure control adversely in the majority of 59 epilepsy patients. Among their patients, treatment with psychotropic drugs in low to moderate doses was associated with improved seizure control in 59% of patients, no change in 32%, and worsened seizure control in 12%. However, several critical sources of error were not addressed. First, no statistical analyses were conducted on the data, making it difficult to infer that the results were not due to chance. Second, the study did not attempt to describe or control for changes in antiepileptic drug (AED) regimens concurrent with psychotropic medication therapy that might reasonably have accounted for the findings. These methodological weaknesses significantly limit the conclusions that can be drawn from this work.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate further the safety of psychotropic medications in an epilepsy population and address methodological limitations of past research. To this end, we assessed the impact of psychotropic medications on seizure status by comparing mean seizure frequency before and during the administration of psychotropic drugs. We also examined the status of AED treatment before and during the period of psychotropic drug administration to determine whether changes in AED type or dose could predict observed changes in seizure frequency over the same time period.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed the records of all patients seen at the New York University School of Medicine Comprehensive Epilepsy Center between 1991 and 1996. Patients who were treated with psychotropic medications for a minimum of two months were identified. Patients were excluded if they lacked complete documentation of clinical data, were on more than one psychotropic medication simultaneously, were not on AEDs before or during the study period, had nonepileptic psychogenic seizures, or had undergone brain surgery in the two-month pre- or post-treatment periods. Fifty-seven patients fit the criteria.

Psychiatric diagnoses and treatment decisions were made by a single psychiatrist (K.A.). DSM-III-R criteria were used.19

Psychotropic medications tended to be introduced slowly and titrated over time. For example, the most common psychotropic we prescribed, nefazodone (n=11), was usually titrated according to the following regimen: initial dose 50 mg bid; in one week, increase to 100–50 mg/day; in two weeks, increase to 100 mg bid. The second most common psychotropic, sertraline (n=9), was usually titrated as follows: initial dose 25 mg/day or 50 mg/day; in one week, increase to 50 mg/ day or 75 mg/day, respectively. Overall, however, the rate of upward titration for psychotropic drugs was determined by the treating psychiatrist on the basis of clinical findings and was not standardized for all patients. Changes in AED regimen during routine clinical care were recorded by the treating neurologist. A detailed review of seizure type and frequency was also obtained during each office visit. Seizure types were classified by use of the International League Against Epilepsy classification system.20

Seizure frequency was calculated in two ways. For descriptive purposes, we grouped patients as having had an “increase” in seizure frequency if the absolute number of seizures (all types recorded) during psychotropic medication therapy was greater than the absolute number that occurred in the two months before treatment began (e.g., no seizures pre-treatment, one seizure during treatment). Similarly, we grouped patients as having had a “decrease” in seizure frequency if the absolute number of seizures (all types recorded) during psychotropic medication therapy was less than the absolute number that occurred in the two months before treatment began (e.g., one seizure pre-treatment, no seizures during treatment). Patients grouped as having had “no change” in seizure frequency had exactly the same number of seizures in the pre- and post- periods (e.g., no seizures prior to or during psychotropic drug treatment). Auras were counted as simple partial seizures.

For the analysis of variance procedure, the actual number of seizures was used as a continuous variable. Two averages were obtained. First, mean seizure frequency prior to psychotropic medication therapy was determined by averaging the total number of seizures (all types recorded) occurring within a two-month pre- treatment period. Second, mean seizure frequency during psychotropic therapy was determined by averaging the total number of seizures occurring within a two- month treatment period. A difference score was also calculated by subtracting the average number of seizures occurring before treatment from that occurring during treatment.

Change in AED status during the study period was measured by classifying changes in both dose and type of AED. AED status for patients on more than one AED during the study period was determined for each drug individually, and these were then averaged together. Categories for dose were as follows: no change=0; small increase (≤20%)=1; small decrease (≤20%)=−1; moderate increase (>20%)=2; moderate decrease (>20%)=−2. Categories for type were as follows: no change=0; adding a drug=1; discontinuing a drug=−1. No patients had AEDs both added and discontinued during the study period. Because seizure status before the study period may influence whether or not a patient is having seizures during the study period, we also examined the independent effect of seizure group: patients not having any seizures (Group 1) or having seizures (Group 2) two months prior to psychotropic drug administration.

The maximum psychotropic drug dosage during the two-month treatment period was calculated as a percentage of the maximum dose specified in the Physician's Desk Reference.21 This yielded a quotient score between 0 and 1 for each prescribed psychotropic drug. Effectiveness of psychotropic drugs on clinical symptoms was assessed at the time of treatment by the prescribing physician using the Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI),22 a scoring system to rate changes in clinical course. Categories of treatment effectiveness were as follows: 1=very much improved; 2=much improved; 3=minimally improved; 4=no change; 5=minimally worse; 6=much worse; 7=very much worse.

Analysis of variance was used to determine whether mean seizure frequency before psychotropic medication administration was equal to or different from mean seizure frequency during psychotropic medication treatment. To examine the potential influence of AED status and seizure group on seizure frequency, and to assess any interactions between AED status and seizure group during psychotropic medication treatment, we conducted a multiple regression analysis. The change in seizure frequency (difference) score was used as the dependent variable. Seizure group and AED dose and type changes, as well as all possible two-way interaction terms and the three-way interaction term, were treated as predictors in the equation. SAS Version 6.12 was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Fifty-one percent of the study patients were male. Mean age (±SD) was 34.4±13.8 years (range 7–69 years). Six patients (11% of the sample) were between the ages of 14 and 16 years. One patient was 7 years old. Age at first seizure ranged from 5 months to 66 years, with a mean of 20.2±15.9 years. Eleven percent of the sample had experienced febrile seizures at some time in the past. Video EEG studies were conducted on 16% of the patients during the study period. Thirty-nine percent had had neurosurgery at some time in the past (but not in the pre-treatment or during-treatment period); of those, 77% began psychotropic medication therapy after surgery. Thirty-eight percent were on one AED, 36% were on two, 23% were on three, and 2% were on four. Table 1 shows the proportion of patients with different seizure types and on different AEDs before and during psychotropic medication therapy. Percentages add to greater than 100% because patients may have more than one seizure type and be on more than one AED.

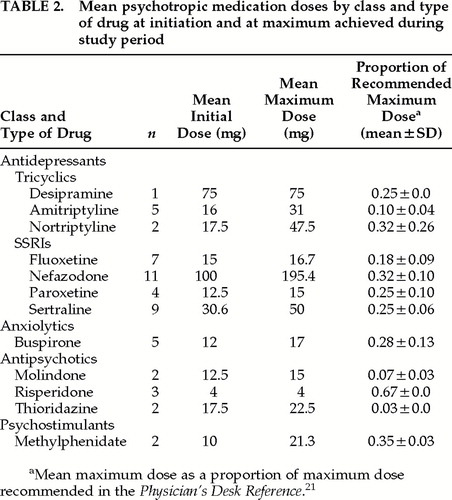

During the study period, the majority of patients (76%) were prescribed antidepressant medications. Of those, 14% were taking one of the tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, desipramine, and nortriptyline), 55% were taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (fluoxetine, nefazodone, paroxetine, and sertraline), and 7% were on other types of antidepressants (bupropion and venlafaxine). Twelve percent were taking antipsychotics (molindone, risperidone, and thioridazine); 9% an anxiolytic (buspirone); and 3% a psychostimulant (methylphenidate). In 22 cases (39%), dosages stayed the same over the two-month study period. In the remaining cases, dosages increased. The highest doses achieved were still largely in the low to moderate range: 77% of patients were taking no more than one-third (0.33) of the maximum dose recommended. Doses (expressed as a proportion of the maximum recommended) ranged from 0.01 to 0.67 (mean=0.28±0.17). Table 2 shows mean doses (starting and maximum) during the two- month study period for each class and specific type of psychotropic medication administered.

Psychiatric diagnoses included depressive disorders (61%), anxiety (30%), organic mental disorders (29%), personality (16%), and psychotic disorders (14%), as well as others such as sleep (4%) and adjustment disorders (4%). Thirty-one patients (54% of the sample) had more than one psychiatric diagnosis. Most patients showed some improvement in psychiatric status, rated according to the CGI system, after treatment with psychotropic medications: 34% were very much improved; 36% were much improved; 21% were minimally improved; and 9% showed no change from baseline. No patient evidenced clinical deterioration during the treatment period.

The typical seizure type experienced before and during treatment with psychotropic medications did not change in 54 out of 57 patients (95%). With regard to seizure frequency, 33% of patients were classified as having experienced a decrease in frequency during the treatment period and another 23% as having experienced an increase. Twelve patients with a decrease in frequency had the number of seizures reduced by more than 2 during treatment with psychotropics (e.g., 36 pre- treatment to 0 during treatment). Seven had the number of seizures reduced by 2 or fewer (e.g., 2 pre-treatment to 0 during the study period). Seven patients with an increase in frequency had seizures increase by more than 2 during the period on psychotropic medication (e.g., 4 pre-treatment to 8 during treatment). Six patients had seizures increase by 2 or fewer during the treatment period (e.g., 0 pre-treatment to 2 during treatment). Most patients (44%) had exactly the same number of seizures in the two months prior to the initiation of psychotropic drug therapy as they did during the first two months of treatment. Of these 25 patients, 18 were seizure-free both before and during treatment.

Mean seizure frequency in the two months before treatment was 55.3±213, ranging from 0 seizures (42%) to 1,500; the median was 150. Mean seizure frequency in the two months after treatment began was 58.3±229, ranging from 0 seizures (51%) to 1,500; the median was 125. The difference was not statistically significant (t=0.23, df=56). We then examined whether seizure group, AED dose and type changes, and their interaction terms (seizure group*AED dose; seizure group*AED type; AED dose*AED type; seizure group*AED dose*AED type) could predict the change in seizure frequency over time. The model overall was not predictive (R2=0.03; F=0.24, df=7, P=0.97), and not one of the seven variables entered in the regression equation emerged on its own as a significant predictor when we controlled for the effects of the other variables.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that treatment with psychotropic medications over a time interval of two months does not appear to affect seizure frequency in the majority of epilepsy patients with coexisting psychiatric pathology treated at our center. Changes in AED regimen during the study period could not account for the findings. In addition, psychotropic medications appear to be effective in this population: psychiatric status improved for more than 90% of the patients during the study period.

Depression may be the most common psychiatric concomitant of epilepsy. Rates are particularly high among patients treated in specialty units or at tertiary care centers where a greater proportion have more severe, medically refractory epilepsy.23–26 In view of the relatively great morbidity associated with mood disorders in epilepsy, it is possible that the consequences of undertreating depression may have a greater impact on patients than the potentially epileptogenic effects of antidepressant medication. It is likely that risk-benefit considerations favor the use of psychopharmacologic treatment in epilepsy when it is psychiatrically indicated. The safety of such treatment in epilepsy may be maximized by the selection of agents with less apparent potential to lower seizure threshold and the introduction of drugs at low dosages with gradual increases.

Estimation of the risk of exacerbating seizures with a psychopharmacologic agent may be based on several types of data, including 1) the incidence of seizures in premarketing clinical drug trials, 2) reports of seizures in postmarketing surveillance, 3) the prevalence of seizures reported in cases of overdoses, and 4) animal models of epileptogenicity. For example, fluvoxamine, mirtazepine, and nefazadone have been associated with low rates of seizures, and clozapine with high rates of seizures, in premarketing clinical trials.21,27 Postmarketing surveillance indicates high seizure risk with chlorpromazine, clozapine, maprotiline, and clomipramine, and these agents should probably be avoided in epilepsy.28 In a 105-site, open-label prospective study (N=3,100), bupropion was found to have a seizure incidence of 0.10% and a cumulative seizure risk of 0.08% in patients receiving therapeutic doses of up to 150 mg bid.29 The rate of seizures with bupropion increases at doses above 300 mg/day and appears strongly dose- related at 450 mg/day and above.30,31 Amoxapine has been associated with high rates and trazodone with low rates of seizures in overdoses.28,32 Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and molindone are among agents with relatively little seizure threshold–lowering activity in animal models.33–35 Adjunctive fluoxetine was shown to have psychotropic as well as anticonvulsant effects in 17 depressed patients with complex partial seizures with and without secondary generalization.36

The treatment practices and methods used in this study probably contributed to minimizing seizure risk. Specifically, we avoided psychotropic medications known to be highly epileptogenic and attempted to select effective drugs that had demonstrated low epileptogenicity. We also took a conservative approach to dosing, as reflected in Table 1, in which initial starting and maximum dosages were often chosen based on evidence that they might be particularly benign with respect to seizure threshold. For example, molindone was chosen partly because of in vitro evidence of its low seizure risk.27 The choice of nefazadone was guided in part by evidence of low seizure incidence (1/3,496 in Phase III trials) as well as the consideration that nefazadone is structurally similar to trazodone, the latter being apparently associated with a low incidence of seizures in overdose.32 Therefore, the results of this study cannot be generalized to all psychotropic drugs or to all dosages, and the safe use of these medications in an epilepsy population may depend on type and dosage.

On the basis of their findings that 59% of patients had a decrease in seizure frequency, Ojemann et al.18 suggested that psychotropic medications may in fact improve seizure control. Although our data do not support this result, we did find that a substantial proportion of patients (33%) experienced a decrease in the absolute number of seizures from the pre-treatment level. Perhaps successful treatment of mood disorders alleviates stress, thereby reducing the likelihood of seizures in at least some patients. Other explanatory factors must also be considered. For example, biological maturation effects and regression to the mean could conceivably account for observed changes in seizure frequency. Spontaneous fluctuations in seizure frequency are quite natural among people with epilepsy,37 and regression to the mean has been reported as a common cause of observed decreases in seizure frequency in pre–post-test research designs.38

Although the empirical evidence from this study generally supports the use of psychotropic medications in epilepsy patients who require psychopharmacologic treatment during the course of clinical care, it is worth exploring whether small subgroups of patients might be more vulnerable to lowered seizure thresholds. For example, we carefully examined the records of all patients who experienced an increase in seizure frequency during the treatment period (n=19). In one case, no temporal association between the administration of the drug and the occurrence of seizures could be made; in another case, a temporal pattern was clearly evident. In the remaining cases, the question of a temporal association between starting psychotropic medication and change in seizure frequency was not clear because of other potentially confounding factors. In particular, one patient was noncompliant, another patient reported simple partial seizures that may have been symptoms of anxiety, and a third patient was undergoing a taper from phenobarbital.

Our study represents one of the few published efforts to build on the initial work of Ojemann and his colleagues.18 We addressed two major limitations of their study by applying statistical analyses and by controlling for the effects of concurrent changes in AED regimen during psychotropic drug therapy. We also delineated clear and reproducible criteria for measuring seizure frequency; considered seizure status before psychotropic therapy as an influential variable; diagnosed patients according to DSM-III-R criteria19 and used a standardized, clinician-rated instrument to evaluate psychiatric response to drug therapy.

There are several other ways to improve on the methodology of studies on the safety of psychotropic medications in an epilepsy population. The addition of a comparison group of epilepsy patients who are not treated with psychotropic drugs would increase internal validity (i.e., with regard to maturation effects and regression to the mean) and further support our contention that the findings cannot be explained by factors extraneous to the study group. Also, it may be important to look more closely at the effects of psychotropic medications on seizure intensity. Several existing seizure severity scales may be appropriate.

Prospective studies with larger sample sizes are needed to establish more reliable estimates of the incidence of drug-induced seizures in this population. We can conclude only that the data do not contraindicate the use of certain psychotropics in low to moderate doses for short periods of time. Although many drug- induced seizures occur early in treatment, it is not clear whether the cumulative seizure rate increases with duration of therapy, as in the case of clozapine.27 However, our clinical experience does not suggest that extended duration of psychotropic drug use increases risk of exacerbating epilepsy. Future studies should consider this question as well as examine the potential effects of class of psychotropic drug, clinical effectiveness, and maximum dosage on seizure frequency and intensity to further detail the safety of psychotropic medication therapy in epilepsy patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Mr. Jeffrey Bahm for his dedicated assistance in data collection.

|

|

1 Dodrill CB, Batzel W: Interictal behavioral features of patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia 1986; 27:564–576Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Mendez MF: Psychopathology in epilepsy: prevalence, phenomenology, and management. Int J Psychiatry Med 1988; 18:193– 210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Silver JM, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC: Psychopharmacology of depression in neurologic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51(suppl):33–39Google Scholar

4 Smith PF, Darlington CL: Neural mechanisms of psychiatric disturbances in patients with epilepsy, in Psychiatric Comorbidity in Epilepsy: Basic Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Treatment, edited by McConnell HW, Synder PJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1998, pp 15–35Google Scholar

5 Carrieri PB, Provitera V, Iacovitti B, et al: Mood disorders in epilepsy. Acta Neurol 1993; 15:62–67Medline, Google Scholar

6 Matthews WS, Barabas G: Suicide and epilepsy: a review of the literature. Psychosomatics 1981; 22:277–378Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Mendez MF, Doss RC: Ictal and psychiatric aspects of suicide in epileptic patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 1992; 22:231–237Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Robertson MM, Trimble MR: Depressive illness in patients with epilepsy: a review. Epilepsia 1983; 24(suppl 2):5109–5116Google Scholar

9 Jick SS, Jick H, Knauss T, et al: Antidepressants and convulsions. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12:241–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Marks RC, Luchins DJ: Antipsychotic medications and seizures. Psychiatric Medicine 1991; 9:37–51Medline, Google Scholar

11 Mendez MF, Cummings JL, Benson DF: Epilepsy: psychiatric aspects and use of psychotropics. Psychosomatics 1984; 25:883– 894Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Popli AP, Kando JC, Pillay SS, et al: Occurrence of seizures related to psychotropic medication among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:486–488Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Rosenstein DL, Nelson JC, Jacobs SC: Seizures associated with antidepressants: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:289–299Medline, Google Scholar

14 Cold JA, Wells BG, Froemming JH: Seizure activity associated with antipsychotic therapy. DICP Ann Pharmacother 1990; 24:601–606Medline, Google Scholar

15 Garcia PA, Alldredge BK: Drug-induced seizures. Neurol Clin 1994; 12:85–99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Mendez MF, Cummings JL, Benson DF: Psychotropic drugs and epilepsy. Stress Medicine 1986; 2:325–332Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Skowron DM, Stimmel GL: Antidepressants and the risk of seizures. Pharmacotherapy 1992; 12:18–22Medline, Google Scholar

18 Ojemann LM, Baugh-Bookman C, Dudley, DL: Effect of psychotropic medications on seizure control in patients with epilepsy. Neurology 1987; 37:1525–1527Google Scholar

19 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

20 Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League against Epilepsy: Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1981; 22:489–501Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Physician's Desk Reference, 52nd edition. Montvale, NJ, Medical Economics Company, 1998Google Scholar

22 Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Rockville, MD, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 217-222Google Scholar

23 Fralin C, Kramer LD, Berman NG, et al: Interictal depression in urban minority epileptics (letter). Epilepsia 1987; 28:598Google Scholar

24 Kramer LD, Fralin C, Berman NG, et al: Relationship of seizure frequency and interictal depression (letter). Epilepsia 1987; 28:62Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Standage KF, Fenton GW: Psychiatric symptom profiles of patients with epilepsy: a controlled study. Psychol Med 1975; 5:152–160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Victoroff JI, Benson DF, Engel J Jr, et al: Interictal depression in patients with medically intractable complex partial seizures: electroencephalography and cerebral metabolic correlates. Ann Neurol 1990; 28:221Google Scholar

27 Devinsky O, Honigfeld G, Patin J: Clozapine-related seizures. Neurology 1991; 41:369–371Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 McConnell HW, Duncan D: Treatment of psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy, in Psychiatric Comorbidity in Epilepsy: Basic Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Treatment, edited by McConnell HW, Synder PJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1998, pp 245–361Google Scholar

29 Dunner DL, Zisook S, Billow AA, et al: A prospective safety surveillance study for bupropion sustained-release in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:366–373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Davidson J: Seizures and bupropion: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 1989; 50:256–261Medline, Google Scholar

31 Johnston JA, Lineberry CG, Ascher JA, et al: A 102-center prospective study of seizures in association with bupropion. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:450–456Medline, Google Scholar

32 Stimmel GL, Dopheide JA: Psychotropic drug-induced reductions in seizure threshold incidence and consequences. CNS Drugs 1996; 5:37–50Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Krijzer F, Snelder M, Bradford D: Comparison of the (pro)convulsive properties of fluvoxamine and clovoxamine with eight other antidepressants in an animal model. Neuropsychobiology 1984; 12:249–254Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Oliver AP, Luchins DJ, Wyatt RJ: Neuroleptic-induced seizures: an in vitro technique for assessing relative risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:206–209Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Pasini A, Tortorella A, Gale K: The anticonvulsant action of fluoxetine in substantia nigra is dependent upon endogenous serotonin. Brain Res 1996; 724:84–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 Favale E, Rubino V, Mainardi P, et al: Anticonvulsant effect of fluoxetine in humans. Neurology 1995; 45:1926–1927Google Scholar

37 Spilker B, Segreti A: Validation of the phenomenon of regression of seizure frequency in epilepsy. Epilepsia 1984; 25:443–449Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Johnson AL: Placebo effects in clinical trials: just regression to the mean? (letter). Epilepsia 1995; 36(suppl 3):S58Google Scholar