The Relationship of Akathisia With Suicidality and Depersonalization Among Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

An association of suicidality and depersonalization with akathisia has been reported, but it is not clear whether these phenomena are specific to akathisia or are nonspecific manifestations of distress. The authors used the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D) to examine the relationships between suicidality, depersonalization, dysphoria, and akathisia in 68 patients with schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder. Akathisia was associated with higher scores on the Ham-D ratings of suicidality, depersonalization, and agitation. In a logistic regression model, depressive mood and subjective awareness of akathisia appeared to be the only predictors of suicidality and depersonalization, respectively. These findings support the association between akathisia and both suicidality and depersonalization. However, these symptoms appear to be nonspecific responses to accompanying depressive mood and the subjective awareness of the akathisia syndrome, respectively.

Akathisia, characterized by a state of subjective and motor restlessness, is a common and unpleasant side effect of antipsychotic medication.1,2 Case reports have described both suicidality and violence as being precipitated by this distressing condition. Shear et al.3 were the first to report two cases of completed suicide occurring impulsively in the context of akathisia in patients with schizophrenia. Similarly, Drake and Ehrlich4 have reported two cases of attempted suicide occurring after antipsychotic drug treatment. Additional case studies by Schulte,5 Shaw et al.,6 and Weddington and Banner7 have reported suicidal ideation or preoccupation attributed to akathisia.

Studies examining the dysphoric effects and behavioral toxicity of antipsychotic medications have also supported the notion that this group of medications may produce adverse behavioral side effects.8–10 Although it has been suggested that akathisia should be considered distinct from the closely associated behavioral side effects of antipsychotics,2 differentiation among these is a complicated task.8 For example, neuroleptic-induced dysphoria, characterized by anxiety, depression, and hostility, may be difficult to differentiate from the subjective manifestations of akathisia.10 Similarly, some cases of psychotic exacerbation reported to follow antipsychotic treatment have been retrospectively determined to be manifestations of undiagnosed akathisia.11,12 Reports and studies linking suicide and/ or akathisia to the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have also implicated a relationship between akathisia and changes in mood and behavior induced by psychotropic medications.13,14 The fact that this association may extend beyond antipsychotics to include SSRI medications increases the clinical importance of this phenomenon, given the wide use of SSRIs in depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Feelings of depersonalization/derealization, disinhibition, impulsivity, and separation anxiety are among other behavioral symptoms reported as probable atypical manifestations of antipsychotic side effects that resemble akathisia.15 The common feature that these side effects share is a subjectively distressed feeling accompanied by somatic feelings such as motor restlessness or tension. Adverse consequences of these side effects include impulsive self-harm behaviors or suicide attempts. However, the relationship between akathisia and suicidality has not been systematically studied. It is also unclear whether the described behavioral manifestations are specific to akathisia or are nonspecific manifestations of distress and anxiety related to the underlying psychiatric illness. Therefore, in this study we investigated the relationship between drug-induced akathisia, dysphoria, suicidality, and feelings of depersonalization. We analyzed the contribution of dysphoria to the suicidality and feelings of depersonalization in akathisia, as well as the influence of subjective versus objective symptoms of akathisia.

Although the underlying mechanisms responsible for akathisia have not been clearly defined, clinical observations suggest that, like other extrapyramidal side effects, it is related to the dopamine D2 binding affinity of antipsychotic medications.16,17 This would imply that some of the novel antipsychotics with relatively less D2 affinity might in some cases produce minimal or no akathisia.

We sought to examine whether the presence of novel antipsychotics influenced the rate of akathisia and its association with any concurrent symptoms or dysphoria and depersonalization. We recognized, however, that novel antipsychotics are difficult to categorize and quantify in clinical studies because their effects, therapeutic or adverse, involve multiple receptor occupancies.18–20 For example, the traditional classifications of chlorpromazine equivalents, defined in terms of D2 occupancy, do not apply readily to novel agents. As a result, we compared three categories of medication in this study, one including typical agents and the other two including newer agents. We distinguished risperidone as a unique category because its D2 receptor occupancy is comparable to that of typical antipsychotics, yet with its serotonin 5-HT2 blocking properties, it is distinct from most typical agents.20 Clozapine and olanzapine were identified as a discrete category as well, given their more diffuse receptor binding affinities and relatively lower D2 affinity.19

METHODS

Data for this analysis were obtained through assessments of subjects participating in inpatient assessments and neuroimaging protocols at the Mental Health Clinical Center, University of Iowa. All subjects participating in these protocols give signed, written informed consent. Inclusion in this analysis was not dependent upon any specific imaging procedure, but occurred by selection of consecutive participants. All patients with a DSM-III-R or DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder were included in the study if they had been on antipsychotics during the month preceding the assessments, without a change in the dose or the type of medication.

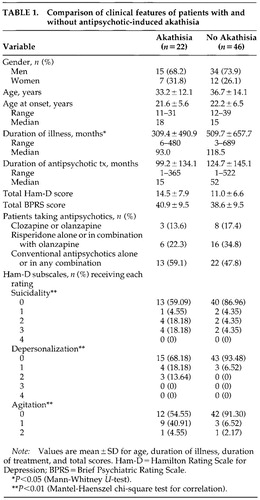

All patients received structured interviews with the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH)21 in addition to the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression Rating (Ham-D)22,23 and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).24 Akathisia was assessed with the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS).25 All patients were jointly interviewed and assessed by two trained raters, whose consensus was entered into analysis. The total sample comprised 68 patients (49 men and 19 women). Characteristics of the sample, divided by presence of akathisia, are described in Table 1. Twenty-two patients had akathisia, defined as a global akathisia rating of at least 1 on the BARS.

The presence of suicidality and feelings of depersonalization were each designated as a categorical variable on the basis of the relevant Ham-D items, with presence defined by a rating of at least 1. Dysphoria was measured by the anxiety-depression subscale of the BPRS, which comprises items for depressive mood, somatic concern, anxiety, and guilt.10 The sum of these items was employed as a continuous variable. The data analysis involved grouping the akathitic and nonakathitic patients, then comparing Ham-D and BPRS anxiety-depression subscale measures by using the Mantel-Haenszel test.

Using this analysis, we determined whether the categorical choice of antipsychotic medication influenced the measures. Thirty-five patients in this sample were on conventional antipsychotics, and the remaining 33 had received newer agents. Our categories for statistical analysis involved three groups: 1) clozapine or olanzapine, 2) risperidone, and 3) conventional antipsychotics, in increasing order of their likelihood to cause akathisia. For patients on more than one antipsychotic, the one more likely to cause akathisia was taken into account.

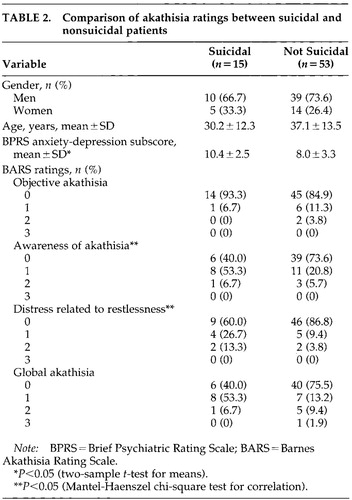

For the purpose of analyzing the relationship between suicidality and the objective and subjective components of akathisia, the whole group was classified on the basis of suicidality. Fifteen patients had a suicide rating of at least 1. These patients were classified as suicidal and the remaining 53 patients as nonsuicidal. The two groups were then compared in terms of their ratings on the individual items on the BARS and the anxiety-depression subscale of the BPRS with the Mantel-Haenszel test for correlations.

RESULTS

In our analysis of medication types between the groups with and without akathisia, we found no difference in the proportion of subjects receiving the three types of antipsychotic medication. (Mantel-Haenszel chi-square= 0.60, df=1, P=0.44). On the basis of this finding, we proceeded with the analysis of other clinical features associated with akathisia.

The akathitic group comprised 22 patients with a global akathisia rating of at least 1 on the BARS, and the comparison group comprised 46 patients with a BARS score of 0. The groups with or without akathisia were not significantly different in terms of age (t=0.9, df=66, P=0.33). The sex distribution was also similar in the two groups (χ2=0.24, df=1, P=0.62). Among patients with akathisia the mean total duration of antipsychotic drug treatment was 99.2 months (SD=134.1), ranging from 1 to 365 months. In the group without akathisia, the mean duration of treatment was 124.7 months (SD=145.1), ranging from 1 to 522 months. The difference was not significant (Mann-Whitney U-test, z=1.41, P=0.16). The types of antipsychotics were not different between the two groups. Because of the diversity of medications used in both groups, including both high- and low-potency conventional agents and novel agents, we were not able to conduct more detailed group analyses of medication type. The total BPRS scores also were not significantly different (t=0.92, df=66, P=0.36). However, the total Ham-D scores were higher in the akathisia group, although the difference did not quite reach statistical significance (t=1.9, df=66, P=0.06).

The presence of akathisia was significantly associated with three items on the Ham-D: 1) suicide: Mantel-Haenszel χ2=7.38, df=1, P=0.007; 2) depersonalization: Mantel-Haenszel χ2=9.15, df=1, P=0.003; and 3) agitation: Mantel-Haenszel χ2=9.40, df=1, P=0.002.

To analyze the relationship between suicidality and the objective and subjective components of akathisia, the entire sample was dichotomized by the presence (n=15) or absence (n=53) of suicidality as described above. The two groups were not significantly different in terms of age (t=1.7, df=66, P=0.07). The gender distribution was also similar in the two groups (χ2=0.28, df=1, P=0.60). The anxiety-depression subscores on the BPRS were significantly higher in the suicidal group (t=2.63, df=66, P=0.01). Suicidality was associated with the two subjective ratings on the BARS: 1) awareness of akathisia: Mantel-Haenszel χ2=3.86, df=1, P=0.049; and 2) distress related to restlessness: Mantel-Haenszel χ2=4.99, df=1, P=0.03. Suicidality was not associated with the objective ratings of akathisia or the total BARS score. Results of these comparisons are displayed in Table 2.

The items on the anxiety-depression subscale of the BPRS and the four items on the BARS were analyzed in a logistic regression model with the presence of suicidality as the dependent measure. Only the depressive mood rating on the BPRS appeared to discriminate between suicidal and nonsuicidal patients (odds ratio=2.27, df=1, P=0.013). In a similar logistic regression model with the presence of depersonalization as the dependent measure, only the subjective awareness of distress rating on the BARS significantly predicted the presence of suicidality (odds ratio=31.26, df=1, P=0.039).

DISCUSSION

Previous reports have drawn attention to a possible association between akathisia and suicidality.3–7 Our findings support this association by demonstrating that among patients with akathisia there was a greater likelihood of suicidality than among those without akathisia. However, it is important to note that when we examined individual akathisia measures on the BARS, it was the subjective ratings of akathisia that occurred more frequently in patients with suicidality compared with nonsuicidal patients. This suggests that the relationship between akathisia and suicidality is accounted for by the subjective component, and not by objectively observed symptoms of akathisia.

Furthermore, these findings imply that the suicidality may be related to internal feelings of distress that are concomitantly expressed both as subjective restlessness and as hopelessness and suicidal ideation. It is possible that akathisia is associated with a constellation of symptoms with both affective and anxious features as well as a motor component. This constellation may not be fully reflected in simple measures of magnitude of motor restlessness. For example, in our analysis using global severity of akathisia (total BARS score) as a continuous regressor, severity of akathisia did not predict the presence of suicidality—suggesting that other clinical features such as anxiousness, dysphoria, and depersonalization are likely to be important factors. This model was supported by our observation that the “depressed mood” item on the Ham-D did discriminate the suicidal group from the nonsuicidal group.

Sachdev15 reported depersonalization and/or derealization attributable to antipsychotic medication in two patients treated for Tourette disorder. Shapiro et al.26 noted feelings of depersonalization, paranoia, and slowed mentation reported in patients with Tourette's syndrome being treated with haloperidol. Feelings of depersonalization may be viewed as nonspecific responses to anxiety in susceptible individuals. However, our results suggest that the subjective awareness of distress, as scored on the BARS, is a significant predictor of depersonalization—perhaps to a greater extent than items on the anxiety-depression subscale of the BPRS. This relationship raises the possibility that the subjective components of akathisia share a common pathophysiologic mechanism with feelings of depersonalization. It is also possible that the subjective phenomena or internal restlessness experienced in akathisia are best described as a surreal feeling and thus are rated as depersonalization, but this quality may not be identical to depersonalization described in other syndromes such as dissociative disorder.

The remaining clinical correlate of akathisia observed in this sample was the rating of agitation on the Ham-D. This finding can be interpreted in several ways. It may be that motor restlessness and agitation present similar appearances and are likely to be rated similarly by observers. It is also possible that the rating of agitation directly measures akathisia in some patients, or that agitation is a separate additive feature related to the severity of psychosis. It has been noted previously that psychotic agitation is one of the most common syndromes to be included in the differential diagnosis of akathisia.27 However, it is important to note the subjective nature of many of the symptoms involved and the substantial overlap among them. The presence of agitation, anxiety, or panic may be misinterpreted as akathisia, and any distress related to these clinical states could therefore be misattributed to akathisia. The possibility of such misattributions is a limitation of the present study. More detailed akathisia measures would be required to better distinguish possible contributions to akathisia from concomitant anxiety symptoms. The overlap between ratings of these features makes interpretation difficult, although clearly the presence of observed agitation suggests a greater burden of illness, whatever the source.

Furthermore, this study did not differentiate between the acute and chronic subtypes of akathisia. These attributes may be important in clinically characterizing the phenomenon. Although acute and chronic akathisia have not been validated by longitudinal studies as two separate clinical entities, it has been reported that inner restlessness may be more common in acute akathisia patients compared with chronic patients.15 The chronic versus acute forms of akathisia and their relationship with suicidality should therefore be a focus of the future longitudinal studies of patients receiving antipsychotics and possibly other medications that may induce akathisia.

Although the lower extrapyramidal side effect risks of the novel agents could imply that, with their wider use, akathisia might become less of a problem among antipsychotic-treated patients, our study does not support that notion. In fact, these results suggest that akathisia may exist even in the presence of novel medications. This finding is limited by the low numbers of individuals receiving each of the novel agents and by the combination of typical and novel agents in some patients. It is possible that larger samples or longitudinal studies will demonstrate a lower incidence of akathisia with novel agents. But it is also possible that akathisia is mediated by other mechanisms that separate it from other extrapyramidal side effects. The unique features of akathisia, such as the associations with suicidality and depersonalization reported here, suggest it is indeed a distinct phenomenon from other side effects and may require specific investigations.

Several other issues beyond the scope of this study will be important to address in the future. One is whether akathisia-associated depressive symptoms tend to occur selectively with certain antipsychotic medications and/or at specific dosage thresholds. Another is the possible overlap between depressive symptoms and negative symptoms, which could influence both the presentation and the likelihood of voicing subjective complaints about akathisia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was presented at the 153rd Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Chicago, IL, May 13–18, 2000.

|

|

1 Sigwald J, Groissiord A, Duriel P, et al: Le traitment de la maladie de Parkinson et des manifestations extrapyramidales par le diethylaminoethyl n-thiodiphenylamine (2987 RP): resultats d'une année d'application [Treatment of Parkinson's disease and extrapyramidal signs with diethylaminoethyl n-thiodiphenylamine (2987 RP): results of a year's trial]. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1947; 79:683-687Google Scholar

2 Barnes TRE, Braude WM: Akathisia variants and tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:874-878Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Shear MK, Frances A, Weiden P: Suicide associated with akathisia and depot fluphenazine treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1983; 3:235-236Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Drake RE, Ehrlich J: Suicide attempts associated with akathisia. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:499-501Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Schulte JR: Homicide and suicide associated with akathisia and haloperidol. Am J Forensic Psychiatry 1985; 6:3-7Google Scholar

6 Shaw ED, Mann JJ, Weiden PJ, et al: A case of suicidal and homicidal ideation and akathisia in a double-blind neuroleptic crossover study (letter). J Clin Psychopharmacol 1986; 6:196-197Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Weddington WW, Banner A: Organic affective syndrome associated with metoclopramide: case report. J Clin Psychiatry 1986; 47:208-209Medline, Google Scholar

8 Singh MM, Kay SR: Dysphoric response to neuroleptic treatment in schizophrenia: its relationship to autonomic arousal and prognosis. Biol Psychiatry 1979; 14:277-294Medline, Google Scholar

9 Van Putten T, Marder SR: Behavioral toxicity of antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48(suppl):13-19Google Scholar

10 Newcomer JW, Miller LS, Faustman WO, et al: Correlations between akathisia and residual psychopathology: a by-product of neuroleptic-induced dysphoria. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:834-838Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Van Putten T, Mutalipassi LR, Malkin MD: Phenothiazine-induced decompensation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 30:102-105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Van Putten T, Mutalipassi LR: Fluphenazine enanthate-induced decompensation. Psychosomatics 1975; 16:37-40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Teicher MH, Glod C, Cole JO: Emergence of intense suicidal preoccupation during fluoxetine treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:207-210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Hamilton MS, Opler LA: Akathisia, suicidality, and fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53:401-406Medline, Google Scholar

15 Sachdev P: Akathisia and Restless Legs. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp 49-50, 162Google Scholar

16 Marsden CD, Jenner P: The pathophysiology of extrapyramidal side-effects of neuroleptic drugs. Psychol Med 1980; 10:55-72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Lishman WA: Organic Psychiatry, 3rd edition. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Science, 1998, pp 640-641Google Scholar

18 Meltzer HY: The role of serotonin in schizophrenia and the place of serotonin-dopamine antagonist antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 15(1, suppl):2-3Google Scholar

19 Baldessarini RJ, Frankenburg FR: Clozapine: a novel antipsychotic agent. N Engl J Med 1991; 324:746-754Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Leysen JE, Gommeren W, Eens A, et al: Biochemical profile of risperidone, a new antipsychotic. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1988; 247:661-670Medline, Google Scholar

21 Andreasen NC: The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH). Iowa City, IA, University of Iowa, 1987Google Scholar

22 Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56-62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Williams BW: A structured interview guide for Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 45:742-7Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Overall JE, Gorham DR: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Res 1962; 10:799-812Google Scholar

25 Barnes TRE: A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:672-676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Shapiro AK, Shapiro ES, Young JG, et al: Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome, 2nd edition. New York, Raven, 1988Google Scholar

27 Chung WSD, Chiu HFK: Drug-induced akathisia revisited. Br J Clin Pract 1996; 50:270-278Medline, Google Scholar