Psychogenic Hemifacial Spasm

Abstract

Facial spasms that distort facial expression are typically due to facial dystonia, tics, and hemifacial spasm (HFS). Psychogenic facial spasms, however, have not been well characterized. The authors sought to 1) determine prevalence of psychogenic facial spasm in patients referred for evaluation of HFS and 2) draw attention to clinical characteristics and potential diagnostic pitfalls. Among 210 consecutive patients referred for evaluation of HFS, 5 (2.4%) received diagnoses of psychogenic facial spasm. All patients were female; mean age was 34.6 years (range 26–45) and mean symptom duration 1.1 years (range 2 wk–2 yr). Onset was left-sided in 3 patients, and the lid was the initial site affected in 2 patients. This series of patients shows that facial spasms, although usually of neurovascular etiology, may be the initial or only manifestation of a psychogenic movement disorder, often associated with an underlying depression.

Hemifacial spasm (HFS) is characterized by tonic and clonic contractions of the muscles innervated by the ipsilateral facial nerve.1–4 Rarely, bilateral HFS has been reported.5 Various studies have demonstrated that the most common underlying etiology is vascular compression of the root exit zone of the facial nerve.6–9 The facial twitchings are frequently exacerbated by stress, anxiety, and fatigue, and some authors have postulated that HFS represents a form of psychosomatic illness.10 One study demonstrated that HFS patients had significantly higher somatization scores than control subjects.11

Psychogenic movement disorders (PMD) are increasingly diagnosed as clinicians have become more sophisticated in recognizing the phenomenology of movement disorders. Fahn and Williams12 categorized PMD as 1) documented, 2) clinically established, 3) probable, or 4) possible, and they and others proposed clinical criteria for the diagnosis of PMD.13–16 Dystonia, tremor, and myoclonus are among the more prevalent PMD encountered in clinical practice.13–17 Psychogenic facial spasms are often included with psychogenic dystonias, but when isolated or present unilaterally, they may be difficult to differentiate from HFS. There may be overlapping clinical features between organic and psychogenic facial spasms, and thus a delay in diagnosis may lead to unnecessary medical or surgical treatment.

The aims of this study were 1) to determine the prevalence of psychogenic facial spasm in patients referred to a tertiary center for evaluation of HFS, and 2) to highlight the clinical characteristics of psychogenic facial spasm and draw attention to potential diagnostic pitfalls.

METHODS

Among 210 consecutive patients referred to us for evaluation of HFS in the Movement Disorders Clinic, Baylor College of Medicine, we diagnosed 5 (2.4%) with psychogenic facial spasm. They exhibited at least four of the following features: 1) acute onset of unilateral facial contractions; 2) inconsistent features such as changes in side and pattern during examination; 3) associated somatizations; 4) reduction or abolishment of facial spasm with distraction; 5) response to placebo, suggestion, or psychotherapy; 6) spontaneous remissions; and 7) normal magnetic resonance imaging/MRAngiography (MRI/ MRA) brain examination.

All patients were examined by a neurologist skilled in recognition of typical and atypical movement disorders (J.J.). All patients were videotaped, and the videotapes were subsequently reviewed by both authors with the specific aim of further characterizing the movement disorder. We excluded patients with facial tics (abrupt onset of a brief, unsustained focal facial movement, usually preceded by a premonitory sensation and suppressible)18 and dystonia (sustained, patterned contractions of muscles producing abnormal movement and posture).19 Because the diagnosis of these hyperkinetic movement disorders is based on clinical phenomenology, electromyographic recordings were not used.

RESULTS

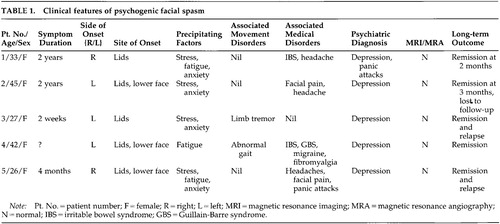

Five of the 210 patients with HFS who satisfied the inclusion criteria for psychogenic facial spasm were studied. All were women, with mean age of 34.6 years (range 26–45 years) and mean symptom duration of 1.1 years (range 2 weeks–2 years). Three patients had left-sided onset, and the lid was the initial site at onset in 2 patients (Table 1). All patients reported stress, fatigue, or anxiety as one of the precipitating factors for their facial spasms. Two patients exhibited movement disorders in other body parts; one had limb tremors and one had abnormal gait. Four also reported associated medical conditions such as migraine, tension headaches, facial pain, fibromyalgia, or irritable bowel syndrome.

Botulinum toxin injections were administered in one patient (by her previous physician) with little benefit. One patient reported a 4-year remission, one had a remission for a few months, one had frequent remissions and relapses, and one had remission at 2-month follow-up. All of our patients were seen by psychiatrists and psychologists before or after our evaluation.

CASE REPORT

Patient #1 is a 33-year-old woman who complained of a 2-year history of twitching of her right facial muscles, following a minor head injury in an automobile accident. The muscle twitchings started on her right upper eyelid, and a few days later, her lower facial muscles were also involved. Occasionally her left lower facial muscles also twitched. The twitchings of her right facial muscles slowly progressed to constant daily closure of her left eyelids and pulling of the right angle of her mouth upwards, affecting many of her daily activities including reading and watching television. She had also noticed contractions of her lower facial muscles on both sides simultaneously. Her right facial twitchings were aggravated by stress, anxiety, lack of sleep, and bright lights, and were relieved by rest and sleep. She had no complaints of tremor, spasm in other body regions, or gait difficulty.

She saw numerous physicians and was diagnosed with hemifacial spasm and treated with various medications without effective relief. She also underwent an MRI and MRA examination of the brain and a cerebral angiogram, which were all unremarkable. Subsequently, a neurologist administered a course of botulinum toxin injection into her right eyelids and facial muscles. She claimed some relief of her facial spasm 1 to 2 months after the injections, but did not return for her follow-up visit. She gave a past history of panic attacks, depression, and tension headache, and she had previously been followed up by a psychiatrist and treated with antidepressants. At the time of our initial consultation, she denied she was troubled by her headache or was depressed, and she was not on any antidepressants.

Neurological examination revealed a pleasant woman with appropriate mood and affect. There were persistent tonic and clonic contractions of her right orbicularis occuli muscles, with pulling of her right facial muscles upwards and to the right. However, the facial muscles contractions were distractible and nonpatterned. There was constant elevation of her left frontalis muscles. In addition, there was also active contraction of her facial muscles on passive movements. She had no focal neurological deficits.

We made the diagnosis of psychogenic facial spasm and explained that her movements were likely to be “stress-induced.” Patient was receptive to our explanation and then volunteered further information that she had previously withheld from us. She was a divorcee with two children and had been depressed since her divorce. In addition, she said she was in the middle of an unresolved litigation involving the automobile accident that preceded the onset of her facial spasm. Following our diagnosis and counseling, she had complete and persistent resolution of her facial spasms.

DISCUSSION

HFS has an estimated prevalence of 14.5 per 100,000 in women and 7.4 per 100,000 in men in the U.S. population.20 It is usually an easily diagnosed condition, although other disorders such as blepharospasm, tics, myokymia, and hemimasticatory spasm are important to consider in the differential diagnosis.21 Various PMD such as dystonia, tremor, myoclonus, tics, and parkinsonism have been reported and diagnostic features proposed.12–16,22

Psychogenic facial spasm was diagnosed in only 2.4% of 210 consecutive patients evaluated for HFS in our clinic. The mean age of our patients (34.6 years) was considerably younger than that of patients with organic HFS, most of whom usually present after age 40.4 In a series of 131 patients with PMD by Williams et al.,22 blepharospasm or other facial movements accounted for only 0.3% (4/152) of all types of psychogenic movements, and only 2 of the 28 PMD patients reported by Factor et al.15 had blepharospasm. We believe, however, that facial spasms frequently accompany other PMD but are not reported separately, since grimacing and facial contortions are often accepted as normal facial expressions in individuals suffering from stress or discomfort.

Interestingly, facial spasms have captured the imagination of many authors of fiction, who have vividly described these movements in people under varying kinds of duress.23 Facial expression is often thought of as a window into human emotions. The relationship of facial expression and emotion has been extensively investigated by Ekman and others,24 who have developed methods to objectively measure facial movements and have examined emotion-specific autonomic and central nervous system activity. The human cerebral cortex is thought to modulate a complex network involving analysis of various forms of stimuli, interpretation of their meaning, and expression of emotional gestures in the form of facial movements and emotional prosody.25 Our cases draw attention to the possibility that distorted facial expression, because of either voluntary or involuntary facial muscle contractions, may obscure the underlying emotion.

The clinical features in our 5 patients were consistent with those reported in other PMD.14,15,22 In addition to the features included in the diagnostic criteria, there were other clinical features that supported the diagnosis of psychogenic facial spasm:

| 1. | None of our patients reported facial spasms during sleep. In a previous study, up to 80% of organic HFS patients had reported persistence of facial movements during sleep.4 | ||||

| 2. | None of the patients demonstrated worsening of spasms during voluntary facial muscle movement. This feature has been noted in 22% to 39% of HFS patients.1,4 | ||||

| 3. | Most patients had lower face involvement at onset, whereas isolated lid involvement is typically present at onset in patients with organic HFS.4,20 | ||||

| 4. | Two patients with bilateral facial spasms had complained of synchronous contractions; this contrasts with organic bilateral HFS, which is characterized by asynchronous spasms.5 | ||||

| 5. | Four patients had a history of irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, or facial pain, conditions that may be associated with functional disorders. | ||||

| 6. | Brain MRI/MRA did not reveal any vascular abnormalities or space occupying lesions. Neurovascular anatomic abnormalities or dolichoectatic vessels have been typically demonstrated in patients with HFS.6–9 | ||||

| 7. | Two patients also complained of facial pain. Although trigeminal neuralgia and HFS may coexist, sometimes referred to as “tic convulsif,” trigeminal HFS is infrequent.4,26 | ||||

A firm diagnosis of a PMD requires extensive historical information as well as a comprehensive neurologic and psychologic evaluation. However, even by the most experienced, great caution must be exercised to avoid the pitfalls that can result in diagnosing an organic movement disorder as psychogenic.

Coexistence of PMD and organic movement disorder has been noted to occur in 10% to 25% of patients with PMD.15,27 Compared with isolated facial spasms (Patients #1, #2, and #5), the presence of coexistent movement disorders in other body regions (Patients #3 and #4) might be helpful in supporting a psychogenic etiology if they are consistent with the clinical criteria for PMD.13–16 Although atypical features suggest a psychogenic cause, it is important to recognize that rare secondary causes of HFS may also appear atypical. For instance, bilateral HFS have been reported in Paget's disease,28 and onset in a lower facial region, with facial pain or numbness, could be associated with space-occupying lesions. In fact, a psychogenic cause was initially considered in a patient reported by van der Biezenbos et al.29 who later was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis; this patient presented with bilateral alternating spasms maximally affecting the lower half of the face.

Although imaging studies are advisable in all patients with atypical features, demonstration of ectatic vessels on MRI/MRA may not totally exclude a psychogenic cause, since such vascular abnormalities have been present in 6% to 20% of normal control subjects.8,9 Diagnosing psychogenic HFS as organic in the presence of MRI/ MRA vascular abnormalities might result in unnecessary surgical intervention. Further complicating the picture, up to one-third of patients with organic HFS have a normal MRI.8

Psychological components superimposing on an underlying organic HFS may create a diagnostic dilemma in some instances. Bratzlavsky and Vander Eecken10 had previously suggested that HFS might be a form of psychosomatic illness, as supported by the observation that all their study HFS patients had complaints of “nervous tension” before the start of the spasm. The frontal muscle has been thought to be particularly sensitive to emotional stress and has been used as an index of general bodily tension. Two recent studies tried to address the psychopathology related to HFS.11,30 Broocks et al.11 found that HFS patients did not differ significantly from population-based reference values for eight out of the nine categories of psychopathology (SCL-90-R), but had significantly higher somatization scores. Scheidt et al.,30 using the same scale (SCL-90-R), however, found a relative lack of psychopathology in HFS patients. In a survey of patients with various forms of facial spasms, more than half of the respondents considered themselves to have psychological problems, which they considered to be secondary to their symptoms.31

We conclude that psychogenic facial spasm may be the initial presentation of psychogenic movement disorders and its presence may indicate an underlying psychological disturbance. Organic hemifacial spasm may have a psychological component, and clinical features can overlap between organic and psychogenic facial spasms. However, clinicians need to be aware of clues suggestive of psychogenic etiology for HFS, and to avoid the diagnostic pitfalls described above. Early diagnosis of psychogenic facial spasm allows the institution of appropriate physical, psychological, and medical therapy and prevents unnecessary treatment with botulinum toxin injections or decompression surgery.

|

1 Ehni G, Woltman HW: Hemifacial spasm. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1945; 53:205-211Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Wilkins RH: Hemifacial spasm: a review. Surg Neurol 1991; 36:251-277Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Digre K, Corbett JJ: Hemifacial spasm: differential diagnosis, mechanism and treatment. Adv Neurol 1988; 49:151-176Medline, Google Scholar

4 Wang A, Jankovic J: Hemifacial spasm: clinical findings and treatment. Muscle Nerve 1998; 21:1740-1747Google Scholar

5 Tan EK, Jankovic J: Bilateral hemifacial spasm: a report of five cases and a literature review. Mov Disord 1999; 14:345-349Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Girard N, Poncet M, Caces F, et al: Three-dimensional MRI of hemifacial spasm with surgical correlation. Neuroradiology 1997; 39:46-51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Barker FG, Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ, et al: Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg 1995; 82:201-210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Adler CH, Zimmerman RA, Savino PJ, et al: Hemifacial spasm: evaluation by magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance tomographic angiography. Ann Neurol 1992; 32:502-506Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Felber S, Birbamer G, Aichner E, et al: Magnetic resonance imaging and angiography in hemifacial spasm. Neuroradiology 1992; 34:413-416Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Bratzlavsky M, Vander Eecken H: Hemifacial spasm: a psychosomatic disease? Acta Neurol Belg 1982; 82:5-11Medline, Google Scholar

11 Broocks A, Thiel A, Angerstein D, et al: Higher prevalence of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in patients with blepharospasm than in patients with hemifacial spasm. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:555-557Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Fahn S, Williams DT: Psychogenic dystonia. Adv Neurol 1988; 50:431-455Medline, Google Scholar

13 Koller WC, Biary NM: Volitional control of involuntary movements. Mov Disord 1989; 4:153-156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Lang AE, Koller WC, Fahn S: Psychogenic parkinsonism. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:802-810Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Factor SA, Podskalny GD, Molho ES: Psychogenic movement disorders: frequency, clinical profile, and characteristics. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1995; 59:406-412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Monday K, Jankovic J: Psychogenic myoclonus. Neurology 1993; 43:349-352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Kim YJ, Pakian S-I, Lang AE: Historical and clinical features of psychogenic tremor: a review of 70 cases. Can J Neurol Sci 1999; 26:190-195Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Jankovic J: Differential diagnosis and etiology of tics. Adv Neurol 2001; 85:15-29Medline, Google Scholar

19 Jankovic J, Fahn S: Dystonic disorders, in Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders, 3rd edition, edited by Jankovic J, Tolosa E. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1998, pp 513-551Google Scholar

20 Auger RG, Whisnant JP: Hemifacial spasm in Rochester and Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1960 to 1984. Arch Neurol 1990; 47:1233-1234Google Scholar

21 Jankovic J: Cranial-cervical dyskinesias: an overview. Adv Neurol 1988; 49:1-13Medline, Google Scholar

22 Williams DT, Ford B, Fahn S: Phenomenology and psychopathology related to psychogenic movement disorders. Adv Neurol 1995; 65:231-257Medline, Google Scholar

23 Perkin GD: Hemifacial spasm. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57:284Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Ekman P: Facial expression and emotion. Am Psychol 1993; 48:384-392Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Heilman KM, Gilmore RL: Cortical influences in emotion. J Clin Neurophysiol 1998; 15:409-423Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Maurice-Williams RS: Tic convulsif: the association of trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm. Postgrad Med J 1973; 49:742-745Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Ranawaya R, Riley D, Lang A: Psychogenic dyskinesias in patients with organic movement disorders. Mov Disord 1990; 5:127-133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Gardner WJ, Dohn D: Trigeminal neuralgia, hemifacial spasm, Paget's disease: significance of association. Brain 1966; 89:555-562Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 van der Biezenbos JBM, Horstink MWIM, van der Vlasakker CJW, et al: A case of bilateral alternating hemifacial spasms. Mov Disord 1992; 7:68-70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Scheidt CE, Schuller B, Rayki O, et al: Relative absence of psychopathology in benign essential blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm. Neurology 1996; 47:43-45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Kowal L, Davis R, Kiely PM: Facial muscle spasms: an Australian study. Aust NZ J Ophthalmol 1998; 26:123-128Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar