Effects of Depression and Parkinson's Disease on Cognitive Functioning

Abstract

This study compared the performance of Parkinson's disease (PD) patients with and without depression, patients with depression alone, and normal control subjects on a cognitive screening instrument, the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) to evaluate the influences of depression and Parkinson's disease on cognition. PD affects overall level of cognitive functioning and, to a lesser extent, DRS Initiation/Perseveration, Construction, and Attention. Diminished memory was primarily related to depression. Treatment of depression may ameliorate aspects of cognitive dysfunction in the PD patient with depression.

Depression is common in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD); prevalence estimates range from 7% to 90%, and 40% is a frequently cited estimate. Half of the PD patients with depression have a major depression and the other half minor depression or dysthymia.1–6 Depression is a risk factor for PD7 and for dementia in PD,8,9 and it is associated with more rapid disease progression,10 cognitive decline,11 and functional disability.12 Recent research suggests that mild depression or dysthymia probably has little if any impact on cognition in PD, and that depression must be of at least moderate severity before it has a significant impact on cognition.6,13 Significant depression appears especially to impair frontal (or executive) functions and memory in PD,14–18 consistent with recent neuroimaging studies showing greater frontal and temporal lobe metabolic abnormalities in patients with depression.19–21

In our previous work14 we compared the performance of Parkinson's patients with depression (PDD) and without depression (PDN) to matched control subjects (NC) on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (DRS). The PDD and PDN groups, carefully matched on demographic and disease characteristics, were impaired relative to NC on the DRS Total, Conceptualization, and Initiation/Perseveration scales. The PDD group demonstrated a greater impairment on each of these three scales. Furthermore, only the PDD group was impaired on the Construction and Memory scales. Because the PDD and PDN groups differed in severity of overall level of cognitive impairment, it was not possible from that study to determine whether the cognitive impairments in PDD and PDN differed only quantitatively or also qualitatively. To address this issue, Tröster et al.15 subsequently compared cognitive performance first in PDD and PDN samples matched for demographic and disease characteristics and then in samples also matched for severity of cognitive impairment. The more pronounced memory and verbal fluency impairments observed in PDD relative to PDN in the first part of the study disappeared when the groups were matched for severity of cognitive impairment, suggesting that differences in cognitive impairment between PDD and PDN are a matter of degree rather than quality.

One limitation of both of these studies was the absence of a comparison group with depression but without Parkinson's disease. As noted by Kuzis et al.,18 the absence of a group with only depression makes it impossible to determine whether cognitive impairments in PDD represent a combined effect of PD and depression or the effect of depression alone. This issue is of particular relevance because the frontal metabolic changes observed in PDD are also observed in patients with depression only, and medial frontal metabolic changes may be especially strongly related to cognitive impairment in depression.22,23 In addition, neuropsychological deficits involving frontal functions and memory are also observed in major depression.24 Studies that have included comparison groups with depression only16,18 have noted frontal and memory impairments in PDD. It has been suggested that although some of the cognitive impairment in PD might be attributable to depression alone, frontal impairments likely represent a combination of the pathophysiologies underlying PD and depression.

Given the varying conclusions drawn in our earlier work and that of other authors who compared PDD, PDN, and depressed groups, this study was designed to elaborate on our earlier work by evaluating the performance of PDD, PDN, and depressed (D) groups relative to a healthy control group (NC) on a cognitive screening examination. Kuzis et al.18 hypothesized that frontal cognitive deficits represent an interaction between PD and D. This hypothesis does not specifically require that frontal cognitive deficits be present in either PD or D alone; indeed, for the deficit to be solely a manifestation of an interaction of PD and D pathophysiologies, the deficit should not be present in either condition alone. If the deficit is present in PDN and D, then the effects of PD and D on frontal cognitive functions may be additive or exponential. Given our own previous finding that PDN and PDD are impaired on DRS Conceptualization and Initiation/Perseveration, and others' work indicating that frontal deficits are present in D, we expected an additive pattern of deficits in PDD.

We hypothesized that both PD groups would be impaired relative to NC on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale25 Total, Conceptualization, and Initiation/Perseveration tasks, with the PDD group showing a quantitatively greater level of impairment than PDN. Because depression affects memory performance in particular, we expected PDD and D to show comparable memory impairments that would be more pronounced than in PDN. Given previous findings, we expected PDD also to perform more poorly than PDN on Construction. If frontal function impairments are attributable to an interaction between PD and depression, then PDD, but not D, should demonstrate impairments on the Initiation/Perseveration and Conceptualization scales of the DRS. Furthermore, for an interaction to be claimed, the performance of the PDD group on these two scales would have to be poorer than that of PD alone (i.e., PDN).

METHODS

Subjects

Medical patients followed in a neurodegenerative disease center (n=52) and psychiatric in- and outpatients at a veterans' hospital (n=19) were recruited for this study. Participants belonged to one of four groups: Parkinson's disease with depression (PDD, n=14); Parkinson's disease without depression (PDN, n=19); depression alone (D, n=19); and a normal control group without Parkinson's disease or depression (NC, n=19). There was some overlap between subjects used in this sample and the cohort of PD patients used in our earlier work.14,15 All subjects underwent extensive medical and neurological or psychiatric workups. All PD and NC subjects were seen by the same neurologist, who evaluated both their PD and possible depression. The diagnosis of PD was based on the presence of two of three cardinal signs: rigidity, bradykinesia, resting tremor, and levodopa responsiveness. The diagnosis of depression in the D group was made by a psychiatrist on the basis of a clinical interview using DSM-IV criteria for major depression or dysthymia. Degree of depression for all participants was quantified with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)26 with a cutoff score of 10. Exclusion criteria for patients were history of neurological illness other than PD (for D, any history of neurological illness); psychiatric illness other than depression; medical illnesses (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) adversely affecting cognition; head trauma with loss of consciousness; and substance abuse.

Normal control subjects were unpaid volunteers residing in the community or in retirement centers, recruited by advertisements and contact with caregiver support groups. Exclusionary criteria included history of neurological or psychiatric illness, self-reported developmental disorder, substance abuse, head trauma with loss of consciousness, use of psychiatric or neurological medication, or taking medications with CNS side effects. The NC subjects did not have significant cognitive impairment (DRS>130) or depression (BDI<10).

The purpose and procedures to be used in the study were fully explained, and all subjects signed an informed consent statement prior to beginning the study.

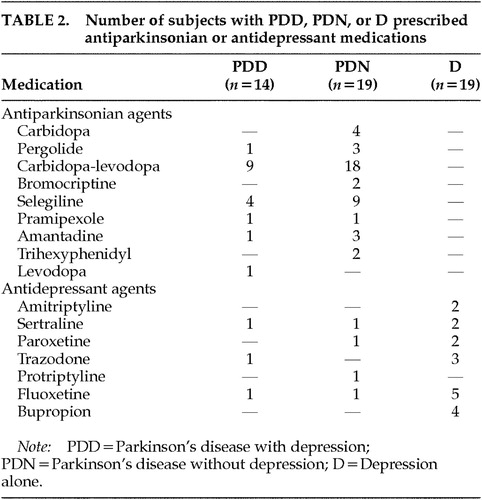

Demographic data and disease characteristics for each of the groups are presented in Table 1. Antidepressant and antiparkinsonian medications used by the subjects with D, PDD, or PDN appear in Table 2. The majority of the participants were male and Caucasian, and the groups were matched for age. The PDD and PDN groups were also matched for age at onset of PD, duration of the disease, and disease severity measured by UPDRS motor scores.

Measures

The BDI was selected as the measure of depression because of its acceptable reliability in identifying depression in older adults.27,28 Further, the validity of using the BDI with PD was demonstrated previously.29 The BDI consists of 21 self-report, multiple-choice items.

Disease severity of PD was measured by the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale motor examination (UPDRS)30 conducted by a neurologist. This score provides an objective measure of the patient's functioning and includes 14 items pertaining to tremor, gait, ease of movement, agility, postural stability, speech, bradykinesia, rigidity, posture, arm swing, hand movement, and facial expression. Each item is scored on a 5-point scale (0 to 4) and items are then added to derive a total score, with higher scores indicating greater levels of impairment. Possible total scores on the motor exam range from 0 to 56. All UPDRS scores reflect the patients' performance on medication.

We used the Mattis DRS in the past and in this study because of its utility as a cognitive measure with PD. Paolo et al.31 showed that, at least as a group, AD and PD show different impairment patterns on the DRS. Furthermore, the validity (convergent and divergent) of using the DRS with PD has been reported in even nondemented PD.32 The DRS is an individually administered measure of cognitive status designed specifically to assess cognitive ability among older adults with brain dysfunction. The DRS is more sensitive to changes in cognitive functioning than the Mini-Mental State Examination and includes subscales that examine five cognitive capacities separately.33 The DRS has adequate validity and good reliability.34 Test-retest reliability for the Total score on the DRS was 0.97, and reliability scores for the DRS subscales were as follows: Attention, 0.61; Initiation/Perseveration, 0.89; Construction, 0.83; Conceptualization, 0.94; and Memory, 0.92.25 The DRS contains 144 items that are similar to the items used in a mental status examination. The items are arranged hierarchically so that an examiner can assume competence and discontinue a section after a few correct responses have been given. There are five subtests to facilitate comparisons between different cognitive tasks, including Attention (e.g., digit span), Initiation/Perseveration (e.g., performing alternating movements), Construction (e.g., copying designs), Conceptualization (e.g., similarities), and Memory (e.g., sentence recall, design recognition). One point is given for each correct item. The number of items within each subtest appears in Table 1. The minimum total score on the DRS is zero, the maximum 144; higher scores indicate better cognitive performance.

Participants were administered the DRS and the BDI by either a neuropsychologist or a trained and supervised neuropsychology technician. The measures were administered and scored by following their standardized, published procedures. Mean scores for each diagnostic group on the BDI and the DRS scales appear in Table 1.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographic and disease characteristics of the four groups as well as mean DRS and BDI scores.

Multivariate analysis of variance was used to compare the two PD groups for age at onset of PD, disease duration, and UPDRS motor score. No significant differences were found (all F<2.5, df=1,31, P>0.1). The difference in antidepressant usage between the PDD and PDN groups was nonsignificant as well (χ2=0.002, df=1, P>0.05). The low number of patients on antidepressant medication in the PDD group likely reflects that some patients were newly depressed and the referring physician was awaiting results of the neuropsychological evaluation before changing or adding medications. Multivariate analysis of variance was also used to test for possible group differences in age or education. There were no significant differences among the four groups in mean age (F=1.5, df=3,67, P>0.2). However, educational differences were significant (F=4.75, df=3,67, P<0.01). Thus, education was included as a covariant in all subsequent analysis.

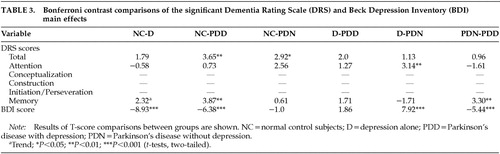

Multivariate analysis of covariance was used to compare the four subject groups' DRS Total and subscale scores (Attention, Conceptualization, Construction, Initiation/Perseveration, Memory), and BDI total score. Bonferroni post hoc analyses were conducted to follow up only on significant main effects by comparing the four diagnostic groups with each other (Table 3). Bonferroni is a commonly used conservative post hoc test that controls for possible Type I error due to multiple comparisons by using a familywise alpha that adjusts for the total number of comparisons made.35,36

Significant main effects were found for the BDI, DRS Total, Attention, and Memory subscales (Table 1). Differences in Initiation/Perseveration and Construction were near significance (P=0.07). Significant P-values for the Bonferroni analyses are reported in Table 3. Bonferroni analyses revealed that the NC and D groups were significantly different on depression and there was a trend toward impaired Memory performance in the D group (P=0.13). PDD were significantly impaired relative to NC on DRS Total, Memory, and BDI. PDN were significantly impaired relative to NC on DRS Total, with marginally impaired Attention (P=0.08). PDD and D groups were not significantly different. The D group performed better than the PDN group on Attention. PDD were significantly more depressed and more impaired on Memory relative to PDN. A trend toward impaired performance on Construction and Initiation/Perseveration tasks was noted for both PD groups relative to the D and NC groups. (Respective P-values: NC-PDD, 0.12, 0.04; D-PDD, 0.39, 1.0; NC-PDN, 0.20, 0.65; D-PDN, 0.64, 1.0.)The PDD group scored the lowest on these tasks.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to compare the pattern of cognitive deficits in samples of depressed PD (PDD), nondepressed PD (PDN), depressed only (D), and normal control (NC) groups so as to highlight potential qualitative and quantitative performance differences on a cognitive screening measure. Comparing and contrasting the performance of the PDD, PDN, and D groups helps to differentiate the relative contributions of depression and Parkinson's disease on cognition within the PDD group.

We hypothesized that both PD groups would be impaired relative to NC on DRS Total, Conceptualization, and Initiation/Perseveration scales (given frontostriatal deficits of PD). This hypothesis was only partly supported. The two PD groups showed poorer overall level of cognitive functioning (DRS Total), but they did not differ significantly on Conceptualization and Initiation/Perseveration. In addition, we expected the PDD group to show greater impairment than PDN if in fact the more severe impairment in the PDD group is due to an interaction of the effects of PD and depression. This was not supported. However, as hypothesized, PDD showed greater impairments than PDN on the Memory scale. The variance of the PDN group's performance pattern with that in our previous study15 likely reflects sample characteristics. The PDN group in our prior study was about 10 years older on average, and this may account for the more widespread cognitive impairment observed in that sample.

Consistent with our hypothesis, we found comparable memory impairment in PDD and D, but not in PDN. Our results suggest, then, that the memory impairment in PDD, as measured with the DRS, might represent solely depression, and that no interaction between PD and depression need be posited as etiological. This finding reinforces the importance of treating depression in PDD and the importance of considering depression as an etiologic factor in dementia in PD. Detection of treatable deficits due to depression is important, because treatment of depression may improve the functioning of people with PDD.2 However, adequate studies are needed to examine changes in cognitive status after successful treatment of depression in Parkinson's disease.

This study is limited by the inclusion of only one cognitive measure. Although the DRS is a widely used and accepted screening tool with older adults, it may not be sensitive enough to detect mild cognitive deficits or sophisticated enough to analyze different components or modalities within any specific cognitive area. For example, further studies of PDD that employ a comprehensive memory test could further clarify the impact of PD and depression. Another limitation is that we had a relatively small sample made up mostly of Caucasian male subjects, and thus the generalization of our findings remains to be demonstrated.

In summary, our findings suggest that depression is primarily responsible for memory impairment in PDD. In contrast, PD itself tends to influence overall cognitive abilities by affecting certain executive functions (DRS Initiation/Perseveration, but not Conceptualization) and, to a lesser extent, Attention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was presented at the National Academy of Neuropsychology Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, October 31, 1996.

|

|

|

1 Tröster AI, Fields JA, Koller WC: Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism, in Textbook of Geriatric Neuropsychiatry, 2nd edition, edited by Coffey CE, Cummings JL. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2000, pp 559-600Google Scholar

2 Fields JA, Norman S, Straits-Tröster KA, et al: The impact of depression on memory in neurodegenerative disease, in Memory in Neurodegenerative Disease: Biological, Cognitive and Clinical Perspectives, edited by Tröster AI. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp 314-337Google Scholar

3 Meyerson RA, Richard IH, Schiffer RB: Mood disorders secondary to demyelinating and movement disorders. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 1997; 2:252-264Medline, Google Scholar

4 Bondi MW, Tröster AI: Parkinson's disease, in Handbook of Neuropsychology and Aging, edited by Nussbaum PD. New York, Plenum, 1997, pp 216-245Google Scholar

5 Taylor AE, Saint-Cyr JA: Depression in Parkinson's disease: reconciling physiological and psychological perspectives. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1990; 2:92-98Link, Google Scholar

6 Starkstein, SE, Mayberg HS: Depression in Parkinson disease, in Depression in Neurologic Disease, edited by Starkstein SE, Robinson RG. Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 1993, pp 97-116Google Scholar

7 Hubble JP, Cao T, Hassanein RES, et al: Risk factors for Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1993; 43:1693-1697Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Stern Y, Marder K, Tang M, et al: Antecedent clinical features associated with dementia in Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1993; 43:1690-1692Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Marder K, Tang M, Cote L, et al: The frequency and associated risk factors for dementia in patients with Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:695-701Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Sano M, Stern Y, Williams J, et al: Coexisting dementia and depression in Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol 1989; 46:1284-1286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Starkstein SE, Bolduc PL, Mayberg HS, et al: Cognitive impairments and depression in Parkinson's disease: a follow-up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990; 53:597-602Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Cole SA, Woodard JL, Juncos JL, et al: Depression and disability in Parkinson's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:20-25Link, Google Scholar

13 Boller F, Marcie P, Starkstein S, et al: Memory and depression in Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol 1998; 5:291-295Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Tröster AI, Paolo AM, Lyons KE, et al: The influence of depression on cognition in Parkinson's disease: a pattern of impairment distinguishable from Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1995; 45:672-676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Tröster AI, Stalp LD, Paolo AM, et al: Neuropsychological impairment in Parkinson's disease with and without depression. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:1164-1169Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Wertman E, Speedie L, Shemesh Z, et al: Cognitive disturbances in parkinsonian patients with depression. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1993; 6:31-37Google Scholar

17 Starkstein SE, Preziosi TJ, Berthier ML, et al: Depression and cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Brain 1989; 112:1141-1153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Kuzis G, Sabe L, Tiberti C, et al: Cognitive functions in major depression and Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol 1997; 54:982-986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Mayberg HS: Frontal lobe dysfunction in secondary depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:428-442Link, Google Scholar

20 Mayberg HS, Starkstein SE, Sadzot B, et al: Selective hypometabolism in the inferior frontal lobe in depressed patients with Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 1990; 28:57-64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Ring HA, Bench CJ, Trimble MR, et al: Depression in Parkinson's disease: a positron emission study. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:333-339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Bench CJ, Friston KJ, Brown RG, et al: Regional cerebral blood flow in depression measured by positron emission tomography: the relationship with clinical dimensions. Psychol Med 1993; 23:579-590Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Dolan RJ, Bench CJ, Brown RG, et al: Neuropsychological dysfunction in depression: the relationship to regional cerebral blood flow. Psychol Med 1994; 24:849-857Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Zakzanis KK, Leach L, Kaplan E: On the nature and pattern of neurocognitive function in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1998; 11:111-119Medline, Google Scholar

25 Mattis S: Dementia Rating Scale. Odessa, FL, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1988Google Scholar

26 Beck AT: Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX, Psychological Corporation, 1978Google Scholar

27 Gallagher, Nies G, Thompson L: Reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory with older adults. J Clin Psychol 1982; 50:152-153Google Scholar

28 Gallagher D, Breckenridge J, Steinmetz J, et al: The Beck Depression Inventory and research diagnostic criteria: congruence in an older population. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983: 51:945-946Google Scholar

29 Levin BE, Llabre, MM, Weiner WJ: Parkinson's disease and depression: psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988; 51:1401-1404Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Fahn S, Elton RL, and Members of the UPDRS Development Committee: Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, in Recent Developments in Parkinson's Disease, vol. 2, edited by Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne DB, et al. Florham Park, NJ, Macmillan Health Care Information, 1987, pp 153-164Google Scholar

31 Paolo AM, Tröster AI, Glatt SL, et al: Differentiation of the dementias of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease with the Dementia Rating Scale. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1995; 8:184-188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Brown GG, Rahill AA, Gorell JM, et al: Validity of the Dementia Rating Scale in assessing cognitive function in Parkinson's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1999; 12:180-188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Salmon DP, Thal LJ, Butters N, et al: Longitudinal evaluation of dementia of the Alzheimer type: a comparison of 3 standardized mental status examinations. Neurology 1990; 40:1225-1230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Spreen O, Strauss E: Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, in A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests. New York, Oxford University Press, 1991, pp 39-41Google Scholar

35 Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS: Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd edition. New York, Harper Collins College Publishers, 1996, pp 51-52Google Scholar

36 Pedhazur EJ: Multiple Regression in Behavioral Research, 2nd edition. New York, CBS College Publishing, 1982, pp 315-316Google Scholar