Apathy and Depression in Cross-Cultural Survivors of Traumatic Brain Injury

Abstract

The disturbance of motivation and its relationship to depression continues to spark contradictory findings among European and North American populations. Could a cross-cultural study shed some light on the situation? This study aims to detect the prevalence of apathy and to test whether the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) can spot the presence or absence of depression in survivors of traumatic brain injury (TBI) in Oman. Eighty subjects who sustained a TBI were given an Arabic version of the AES and were also interviewed with the semistructured Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). The authors found that the incidence of apathy and depression among Omani people who sustained TBI is similar to that reported elsewhere. The AES has poor discriminatory power in identifying cases of depression. These findings emphasize the importance of developing assessment tools that are culturally sensitive in light of the rising incidence of TBI in developing countries such as Oman.

Oman is an Arab-Islamic country that lies on the eastern side of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered on the East by the Indian Ocean and on the West by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Oman’s population has an extremely large youth base, with about 65% below the age of 20 years.1 Each year, it is estimated that 0.3% to 0.4% of the population of Oman will incur brain injuries, principally from road traffic accidents, domestic accidents, and falls from date palms (a major cash crop).2,3 Other major causes of brain injuries in Oman are the “diseases of affluence”—mainly diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and obesity—that lead to cerebral vascular diseases.1 Acquired brain injury is a growing public health problem in Oman.4 For these victims, healthcare protocols have been limited to the reduction of mortality in the past several years. With the advent of effective emergency care, faster transportation, and improved acute medical management, the mortality rate among the brain injured has decreased in Oman. These advances have left the medical system with increased responsibility in addressing the needs of the survivors, especially the long-term issues of disability.5,6 Disability results not only from physical and cognitive impairment, but also from deficits in the areas of emotion and initiation as well.7–9 These latter deficits often provide a vexing obstacle to the realization of a more advanced functional ability.10 The issue of lack of initiative or passivity is not unique to that with acquired brain injury. The incidence of passivity has been shown to vary from 18% to 90% for various neuropsychiatric and neurological populations.6,11–16

Marin,17 Starkstein, Petracca, Chemerinski,18 and Andersson, Krogstad, and Finset13 have suggested that the common overriding characteristic of these disorders could be encapsulated into a concept of apathy. Marin17,19 has operationalized the concept of apathy in terms of ability, interest, initiation of activity, motivation, awareness, and effective functioning into an 18-item rating scale, the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES). Although the AES was essentially designed to diagnose and measure the severity of apathy,17 it has also been employed for case identification in neurological populations.6,13,20 Its psychometric properties have been found to be effective in some studies14,15,21–23 but not in others.24 Interestingly, the concept of neurologically based apathy has been difficult to distinguish from depression in some patients.25 Both seem to occur in significant proportions in the brain injury population.26 While some studies have noted that apathy and depression seem to refer to separate entities, these studies were not executed in cross-cultural populations. Further, few studies have examined the validity of the AES in cross-cultural populations. It is not clear that a measure of apathy developed in a Western culture might have such a broad applicability as to appropriately apply in Oman. The AES may rely on behaviors and attitudes essentially limited to European and North American cultural groups. Further, it is not clear that the problem of passivity or apathy that is so prevalent among those with brain injury in the West might also be as prevalent in the culture of Oman. If we are to apply the AES to those who suffer brain injury outside of the European cultural catchment, we must first explore whether such a use is appropriate. As an initial step, studies are needed to clarify whether a disturbance of motivation is similarly prevalent or disruptive in cross-cultural populations. Second, it is important to determine whether there is a distinction between depression and apathy in the Omani population. For example, Pang et al.27 showed that, in contrast to their American counterparts, patients with Alzheimer’s disease in a Chinese environment exhibit apathy and depression that are unlikely to be viewed with contempt or as a social burden by their society. In the Arab world, disturbances of mood frequently manifest in a somatic metaphor28 that contrasts with the “cognitive metaphor” often discussed among populations in the industrialized world. To explore these issues, therefore, it is important to first measure the incidence of apathy. We, therefore, sought to use the AES to measure the incidence of apathy in an Omani brain-injury population. Since the AES elicits symptoms of both apathy and depression, we also examined whether AES could discriminate between depression and apathy among patients in our sample.

The specific aims of this study were 1) to screen and detect the prevalence and severity of apathy among males and females who have sustained traumatic brain injury (TBI) in Oman; 2) to assess the validity of the Arabic version of the AES as a screening instrument for a TBI population in Oman; and 3) to determine whether depression and apathy could be seen as separate entities in an Omani brain-injury population.

METHODS

Subjects

The subjects comprised consecutive patients who had sustained TBI and who were referred to a state-run tertiary care facility for evaluation and treatment. In this study, TBI is defined as an injury to brain tissues caused by an external mechanical force as evidenced by a loss of consciousness, posttraumatic cognitive and behavioral changes or an objective neurological finding that can reasonably be attributed to the TBI on a physical or cognitive and behavioral status examination. Patients attending the outpatient clinic at the Sultan Qaboos University Hospital for posttraumatic follow-up with complaints of depression, changes in personality, cognitive deficits, and posttraumatic physical impairments were included in the analysis.

Patients were invited to participate in an anonymous survey and interview to assess their cognitive, behavioral, and emotional state. This invitation was extended during routine outpatient visits. None of the invited patients declined to be interviewed or to complete the assessment measure. Informed consent was obtained.

The exclusion criteria included preinjury psychiatric or neurological history other than those resulting from a TBI. In addition, non-Omani patients and those who were known to have sensory or cognitive impairments that would preclude completion of the protracted assessment were excluded from the sample. The study was approved by both the Ethics Committee for Human and Clinical Research and the Medical Research Committee (project number MED 99-4) of the College of Medicine, Sultan Qaboos University. The final sample included 80 patients.

Procedures

Clinical and demographic information.

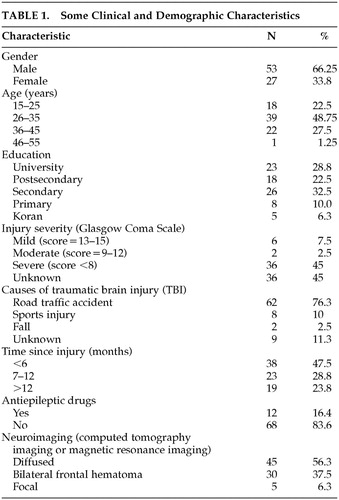

The demographic and clinical information of the patients is presented in Table 1. Various clinical and demographic data were sought retrospectively and prospectively either through the patients themselves or from a person accompanying the patients. Some information was gathered from referral notes and medical records. This included age, sex, level of literacy, level of education, type of accident, time since injury, radiological data, and history of loss of consciousness. Where available, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)29 was used for classifying the severity of the injury. A GCS score of 13 to 15 was considered mild; 9 to 12 was considered moderate; and eight or less was considered severe.

Assessment of apathy.

The Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) can be administered in three different forms: self report, informant report, and clinical interview. A modified self-report version has also been validated for use with Parkinson’s disease patients.30,31

For this study, apathy was quantified using the self-report version of the AES. To make the AES dialectally adaptive to an Omani sample, experienced staff members produced another Arabic-language version of the scale by a method of back-translation.32 Following preliminary trials, it was considered necessary for the interviewer to read all items to the patients in order to accommodate various sensory and motor impairments as well as to allow the inclusion of those subjects who were not literate. Therefore, interviewers were trained to read out the items of the AES in the local dialect of spoken Arabic and to rate the responses accordingly. Using this method, we noted an adequate interrater agreement on the various items of the scale (r=0.86, p value<0.001). The AES consisted of 18 items covering interest, initiation of activity, motivation, insight and emotionality.17 Each item was rated on a scale of 1 to 4. A composite score for a patient, therefore, ranges between 18 and 72. The higher scores indicate a heightened apathetic state. For this study, a cutoff score of 34 or greater was used to define the presence of apathy.6,13,24

Structured interview.

All subjects participated in the semistructured interview using the style and format of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI).33 The CIDI was developed to give a reliable and valid assessment of the specific and general psychopathology of emotional disorders according to the definitions and criteria of international classification of disease (ICD-1033 and DSM-IV34). It was developed as a collaborative project between the World Health Organization and the U.S. National Institutes of Health. It is the most widely used structured diagnostic interview in the world.35 The CIDI has been designed for use in a variety of cultures and settings.36,37 It is primarily intended for use as an epidemiological tool but can be used for other research and clinical tasks.

The screening and probing questions from the CIDI were translated using back-translation32 to achieve conceptual equivalence in the Omani dialect. The interview was conducted by two of the authors who had received training in its use. A diagnosis of depression was made according to both the DSM-IV34 and ICD-1033 criteria after detailed discussion between the authors. The structured interview was conducted without the interviewer’s knowledge of the results from the AES. No attempt was made to place the subjects into other diagnostic categories.

Statistical Analysis

The data were entered into a microcomputer and analyzed using Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS).38 The chi-square test was used to test for association among the parameters. A receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was calculated to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the AES for every possible threshold score.

RESULTS

Demographic Information

Clinical and demographic information are summarized in Table 1. There were 53 men (66.3%) and 27 women (33.8%). The majority of the patients were in the age range of 26 to 35 years. The mean age for the male patients was 29.70 years (SD=7.48, range=17–45) and 33.52 years (SD=7.08, range=22–50) for the female patients. The overall mean age was 30.99 years (SD=7.52). Twenty-three patients (28.8%) had university degrees. Eighteen (22.5%) had postsecondary school diplomas; 26 (32.5%) completed secondary school; eight (10.0%) had a primary school education only, while five (6.3%) were either illiterate or had some basic literacy in Koranic text.

All the patients sustained closed head injuries. The injuries of 61 patients (76.3%) were due to road traffic accidents. Ten (12.5%) incurred their injuries through falls or sports accidents. The cause of injury was unknown for the remaining nine patients (11.3%). The majority of the patients were less than 6 months postonset of brain injury. The average time since the injury was 8.35 months with SD of 4.50 months. The time since the injury ranged from 1 to 18 months.

Neuroimaging data obtained from radiological reports (mostly from computerized tomography scans showed diffuse injuries in 45 (56.3%) of the patients. Five (6.3%) showed focal injuries while 30 (37.5%) had frontal hematomas. Twenty-nine patients (42.6%) were in a coma for up to 10 days. There was insufficient information to determine coma duration for the remainder of the patients. According to the GCS scores, six (7.5%) were mild; two (2.5%) were moderate; and 36 (41.1%) were rated as severe. No GCS scores were available for the remaining patients. Twelve patients (16.4%) were on antiepileptic drugs.

Assessment of Apathy

Patients who reported scores on the AES of 34 points or higher were defined as representing “possible subclinical cases of apathy.” Out of 80 patients, 16 (20%) scored 34 or higher on the AES. A 95% confidence interval was 11.0% to 29.0%. The overall mean AES score was 57.25 (SD=14.19). Out of 53 men, 10 (18.9%) scored above 34 on the AES, while 6 of the 27 women (22.2%) scored above 34. The 95% confidence interval estimates for men and women were respectively 8.0% to 29.8% and 5.5% to 39.0%. Both men and women appear to be homogeneous with respect to the AES score (p=0.772). The proportion of women that were classified as positive by the AES was statistically the same as the proportion of men.

Effectiveness of the Apathy Evaluation Scale

Thirty-seven patients (46.3%) met the CIDI’s criteria for depression. The 95% confidence interval estimate of the proportion of patients with depression was 35.1% to 57.4%. Out of this number, 23 (43.4%) were men, and 14 (51.9%) were women. The proportion of women classified as depressed by the CIDI criteria was the same as the proportion of men (p=0.488). The 95% confidence interval estimates were 29.6% to 57.2% and 31.7% to 72.0% for men and women, respectively. Thus, male and female patients were homogeneous with respect to the CIDI criteria.

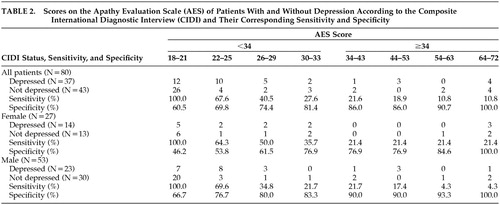

Out of a total of 37 subjects detected by the CIDI criteria (Table 2), only 16 were above the cutoff score of 34 on the AES. The sensitivity of the AES for isolating those with depression was 21.6% (i.e., the percentage of genuine cases identified). Of those that were not classified as depressed by the CIDI criteria, eight scored above the AES cutoff of 34 for apathy. Further, a test of association between the CIDI and AES showed independence (p=0.785). These data do not, therefore, suggest a relationship between the two constructs.

Using a study of the ROC curve, it was determined that the sensitivity for including patients with depression was 40.5% and the specificity 74.4% when the AES cutoff was made at 28. When the cutoff was reduced to 23, however, sensitivity increased to 64.49%, and the specificity dropped to 62.8%. Similar results can be obtained when the sample is divided into men and women (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The first aim of this study was to measure the incidence of apathy as well as depression in a population of brain injury survivors in Oman and to compare these data with those obtained in other cultures and populations. In this study sample, the proportion of the probable cases of apathy was 20%, utilizing an AES cutoff score of 34. This is similar in frequency to data obtained by self-report within studies of brain injury survivors in the Euro-American population. A higher incidence has been reported elsewhere. Grinstead41 reported that 59.2% of patients who have endured TBI are marked by poor motivation. Andersson et al.9 noted similar behavioral symptoms in 57% of stroke patients, in 46% of patients with a TBI, and in 79% of patients who sustained anoxic episodes. Kant et al.6 noted that 60% of TBI patients are deficient in motivated behavior. In neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s diseases, the incidence is as high as 90%.14–17 Although methodological differences may account for some of these discrepancies, the available epidemiological evidence suggests that the incidence of apathy fluctuates in complex ways. To our knowledge, this is the only report on the incidence of apathy using the AES in a cross-cultural sample. The rate of clinical depression noted in this study was 46.3%, similar to studies in other cultures,42,43 though the measurement tools for the determination of depression have varied widely.

Using the CIDI criteria as a yardstick for depression, the data in this study suggest that the AES is not a sutiable tool for identifying those with depression. The sensitivity and specificity of the AES were 24% and 69.6%, respectively, for CIDI determined depression. This suggests that the two tools measure distinct entities. This, of course, is difficult to completely assess, as the rate of overlap between the symptoms of depression and of apathy is significant. The second aim of this study was to examine the prevalence of depression among survivors of TBI. The present data suggest that approximately 46% of the subjects who sustained TBI suffer clinical depression according to both DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria. This rate of depression is consistent with other studies suggesting that depression is frequently present among the survivors of TBI.44 This is in agreement with emerging evidence that, although mood disorders are often presented in culturally somatic language of distress,28 most patients freely admit to having depressive illness upon inquiry.45,46 Alternatively, the situation in Oman may be parallel to those in other developing countries where improved education has coincided with a reduction of traditional ways of expressing emotions.28 Therefore, education has acculturated them with a language of distress that is compatible with items featured in the CIDI.

Unlike previous studies where depression was assessed with a structured self-rating scale,24,47 this study utilized a semistructured interview, the CIDI. Studies have suggested that the CIDI is reliable and efficient in its assessment of symptoms of mood because it has inherent leeway in eliciting information by virtue of an open-ended format.44 It has also been shown to have ecological validity in various cultural settings48 where its open-ended format is likely to capture distress that may not be apparent if information is elicited using structured assessment measures.49

Depression among the survivors of TBI has not previously been reported from the Arabian Gulf. Previous studies from industrialized countries have employed scales such as the Beck Depression Inventory,50 the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale,51 and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale52 to elicit information on depression. It is important to note that these scales were originally devised for psychiatric populations. There is a paucity of information on their validity in neurological populations.44,53 Traumatic brain injury patients may be unique. For example, it is generally agreed that many patients with TBI have diminished insight.39 Thus, patients may report a distorted sense of their own well-being. One possibility for future studies would be to use self-report measures of cognitive deficiency and compare them with objective tests of self-awareness.54 However, using such a strategy is inherently problematic. For instance, if someone is unaware of being depressed, can they be said to be truly depressed since the essence of depression is a subjective dysphoria? Further research in this area is, therefore, indicated, bearing in mind that the survivors of TBI might themselves be a “cross-cultural population.”

LIMITATIONS, THEORETICAL, AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Generalizations from this study should be made with caution. The present sample was a small and heterogeneous cohort with variations on the duration and severity of injury. It may, therefore, not be representative of TBI survivors in Oman. The rates of apathy and depression may be influenced by the fact that the study was conducted at a tertiary care facility located in an urban area. The fact that this sample is relatively older than survivors in other populations,55 further suggests that the present population of TBI survivors might be skewed in favor of a particular group. The results may also have been influenced by a sociocultural factor unique to Oman. It is possible that many victims of TBI do not receive medical attention because the injury is construed as an act of fate or may be simply hidden to avoid social stigma.56 It appears the majority (36/44) of patients in this study who presented themselves for medical attention did so with severe impairment as indexed with GCS. This view not withstanding, the data were collected in the only center in the country with the resources suitable for diagnosis of survivors of TBI. The Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, which provided a setting for this study, caters to a mixed social class, featuring a cross section of Omani society of nearly 1.5 million people.57 The majority of the victims of TBI were young, which is consistent with the emerging patterns of brain injury related to a sharp rise in road traffic accidents in Oman.56

The validity of dimensional instruments such as the AES is likely to be limited, compared with the categorical approach of the CIDI. Although all items in the AES were translated to achieve conceptual equivalence in the Omani dialect, their usefulness could still be hampered by certain subtle linguistic and conceptual misunderstandings that might not have been apparent during translation and piloting. Future studies should carefully address the issue of culturally sensitive measures. Due to cognitive problems in patients with TBI in this study, the items were read to all the subjects rather than the subjects self-administering the AES. It is possible that this approach may have resulted in a reluctance to reveal sensitive feelings that may have been more fully elicited in the more thorough interview setting of the CIDI. While this issue seems more germane to the issue of the severity of the injury rather than cultural issues, this mode of presentation could have altered the results of the test.

This study, to our knowledge, is the first to show the incidence of both apathy and depression among survivors of TBI from a nonindustrialized country. More studies in other cross-cultural communities are therefore indicated. Future studies should establish psychometric properties of the instruments on Omani samples as well as develop culture-specific assessment instruments using local gold standards.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their appreciation for the time and effort given by the patients and caregivers who participated in this research and Mr. Charles Asante for his technical support.

|

|

1 Sulaiman AJM, Al-Riyami A, Farid S, et al: Oman Family Health Survey 1995. J Trop Pediatr 2001; 47(suppl 1):1–33Google Scholar

2 Al-Marshudi AS: Traditional irrigated agriculture in Oman—operation and management of the Alaj system. Water Int 2001; 26:259–264Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Zaidan ZAJ, Burke DT, Dorvlo ASS, et al: Deliberate self-poisoning in Oman. Trop Med Int Health 2002; 7:549–556Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Deen JL, Vos T, Huttly SRA, Tulloch J: Injuries and noncommunicable diseases: emerging health problems of children in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 1999; 77:518–524Medline, Google Scholar

5 Kant R, Duffy JD, Pivovarnik A: Prevalence of apathy following head injury. Brain Inj 1998; 12:87–92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Al-Adawi S, Powell JH, Greenwood RJ: Motivational deficits after brain injury: a neuropsychological approach using new assessment techniques. Neuropsychology 1998; 12:115–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Wroblewski BA, Glenn MB: Pharmacological treatment of arousal and cognitive deficits. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1994; 9:19–42Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Andersson S, Gundersen PM, Finset A: Emotional activation during therapeutic interaction in traumatic brain injury: effect of apathy, self-awareness and implications for rehabilitation. Brain Inj 1999; 13:393–404Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Galynker I, Prikhojan A, Phillips E, et al: Negative symptoms in stroke patients and length of hospital stay. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:616–621Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Al-Adawi S, Dawe GS, Al-Hussaini AA: Aboulia: neurobehavioral dysfunction of dopaminergic system. Med Hypotheses 2000; 54:523–530Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Andersson S, Krogstad JM, Finset A: Apathy and depressed mood in acquired brain damage: relationship to lesion localization and psychophysiological reactivity. Psychol Med 1999; 29:447–456Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Landes AM, Sperr SD, Strauss ME, et al: Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49:1700–1707Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Isella V, Melzi P, Grimaldi M, et al: Clinical, neuropsychological, and morphometric correlates of apathy in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2002; 17:366–371Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Thompson JC, Snowden JS, Craufurd D, et al: Behavior in Huntington’s disease: dissociating cognition-based and mood-based changes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002; 14:37–43Link, Google Scholar

15 McPherson S, Fairbanks L, Tiken S, et al: Apathy and executive function in Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2002; 8:373–381Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Jahanshahi M, Frith CD: Willed action and its impairments. Cognitive Neuropsychology 1998; 15:483–533Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Marin RS: Apathy and related disorders of diminished motivation, in American Psychiatric Association Review of Psychiatry, vol 15. Edited by Dickstein LJ, Riba MB, Oldham JM. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996, pp 205–241Google Scholar

18 Starkstein SE, Petracca G, Chemerinski E, et al: Syndromic validity of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:872–877Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Marin RS: Differential diagnosis and classification of apathy. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:22–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Resnick B, Zimmerman SI, Adelman A, et al: Utilization of the Apathy Evaluation Scale as a measure of motivation in the elderly. Rehabil Nurs 1998; 23:141–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Ramirez SM, Glover H, Ohlde C, et al: Relationship of numbing to alexithymia, apathy, and depression. Psychol Rep 2001; 88:189–200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Lampe IK, Kahn RS, Heeren TJ: Apathy, anhedonia, and psychomotor retardation in elderly psychiatric patients and healthy elderly individuals. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2001; 14:11–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Marin RS, Firinciogullari S, Biedrzycki RC: Group differences in the relationship between apathy and depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 1994; 182:235–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Glenn MB, Burke DT, O’Neil-Pirozzi T, et al: Cutoff score on the Apathy Evaluation Scale in subjects with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2002; 16:509–516Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Corey MR: A comprehensive model for psychosocial assessment of individuals with closed head injury. Cognitive Rehabilitation 1987; 5:28–33Google Scholar

26 Van Zomeran A, Van Den Burg W: Residual complaints of patients two years after severe head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985; 48:21–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Pang FC, Chow TW, Cummings JL, et al: Effect of neuropsychiatric symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease on Chinese and American caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 17:29–34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Al-Lawatia J, Al-Lawatia N, Al-Siddiqui, et al: Psychological morbidity in primary health care in Oman. Sultan Qaboos University J Sc 2000; 2:105–110Google Scholar

29 Teasdale GM, Jennett B: Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: practical scale. Lancet 1974; 2:81–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Starkstein SE, Mayberg HS, Preziosi TJ, et al: Reliability, validity, and clinical correlates of apathy in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 4:134–139Link, Google Scholar

31 Okada K, Kobayashi S, Yamagata S, et al: Poststroke apathy and regional cerebral blood flow. Stroke 1997; 28:2437–2441Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Al-Adawi S, Al-Ismaily S, Martin R, et al: Psychosocial aspects of epilepsy in Oman: attitudes of health professionals. Epilepsia 2001; 42:1476–1481Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), core version 1.1. Geneva, WHO, 1993Google Scholar

34 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM-IV). Washington, DC, APA, 1994Google Scholar

35 Ustun TB, Andrews G: International classifications and the diagnosis of mental disorders, in Handbook of Psychiatric Care. Edited by Maj M, Gaebel W, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Sartorius N. Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, 2002, pp 25–46Google Scholar

36 Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, et al: The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1069–1077Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Wittchen HU, Robins LN, Cottler LB: Cross-cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): the multicentre WHO/ADAMHA field trials. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 159:645–653Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 SPSS 9.0 for Windows. Chicago, SPSS, 1999Google Scholar

39 Oddy M, Humphrey M, Uttley D: Subjective impairment and social recovery after closed head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1978; 41:611–616Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 Oddy M, Coughlan T, Tyerman A, et al: Social adjustment after closed head injury: a further follow-up seven years after injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985; 48:564–568Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Grinstead P: Fractured policy on head injuries. Hospital Doctor, Feb 20, 1997, p 36Google Scholar

42 Gualtieri CT, Cox DR: They delayed neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 1991; 5:219–232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 Silver JM, Yudofsky SC: Psychopharmacological approaches to the patient with affective and psychotic features. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1994; 9:61–77Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Kreutzer JS, Seel RT, Gourley E: The prevalence and symptom rates of depression after traumatic brain injury: a comprehensive examination. Brain Inj 2001; 15:563–576Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 Patel, V: Cultural factors and international epidemiology. Br Med Bull 2001; 57:33–45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, et al: An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:1329–1335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 Green A, Felmingham K, Baguley IJ, et al: The clinical utility of the Beck Depression Inventory after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2001; 15:1021–1028Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 Abou-Saleh MT, Ghubash R, Daradkeh TK: Al-Ain Community Psychiatric Survey, I: prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001; 36:20–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 Lesser IM: Cultural considerations using the structured clinical interview for DSM-III for mood and anxiety disorders assessment. J Psychopathol Behav 1997; 19:149–160Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK: Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd ed, Manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1996Google Scholar

51 Montgomery SA, Asberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53 Sliwinski M, Gordon WA, Bogdany J: The Beck Depression Inventory: is it a suitable measure of depression for individuals with traumatic brain injury? J Head Trauma Rehabil 1998; 13:40–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 Viguier D, Dellatolas G, Gasquet I, et al: A psychological assessment of adolescent and young adult inpatients after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2001; 15:263–271Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55 Jager TE, Weiss HB, Coben JH, Pepe PE: Traumatic brain injuries evaluated in US emergency departments, 1992–1994. Acad Emerg Med 2000; 7:134–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56 Al-Adawi S, Burke DT: Revamping neurorehabilitation in Oman. Sultan Qaboos University J Sc 2001; 3:35–38Google Scholar

57 Statistical YearBook: Sultanate of Oman: Ministry of National Economy, 29th ed. Muscat, Oman, Information and Publication Centre, 2001Google Scholar