Psychopathology in Verified Huntington’s Disease Gene Carriers

Estimated rates for lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Huntington’s disease patients vary widely between 33% and 76% 3 , 10 The investigated neuropsychiatric symptoms include depressed mood, anxiety, irritability, apathy, obsessions and compulsions, and psychosis. This variation in prevalences can be explained by the use of different assessment methods with varying definitions of neuropsychiatric phenomena. No follow-up studies covering a longer period have been performed.

For many patients and their relatives, these neuropsychiatric symptoms constitute the most distressing aspect of Huntington’s disease and often constitute reason for hospitalization. 12 Whereas severity of motor and cognitive dysfunction is only moderately related to the severity of functional decline, behavioral symptoms and psychiatric disorders seem to have a more severe negative effect on daily functioning. 13 Previous findings have suggested, although inconclusively, that psychopathology as well as cognitive dysfunction may precede the onset of motor symptoms in many patients. 14 – 16

To get more insight into the occurrence and prevalence of behavioral problems and psychiatric disorders in Huntington’s disease, we review the literature on psychopathology in verified Huntington’s disease gene carriers, with particular reference to its relationship with disease onset and progression, as well as possible underlying neuropathological pathways. We conclude with several recommendations for future research.

Data Sources

We searched two literature databases, Embase and PubMed, for prevalence of psychopathology in Huntington’s disease. We used a variety of search terms, all synonyms for Huntington’s disease and various (neuro)psychiatric phenomena. Where possible, these were mapped onto the following standard database terms (subject headings/MeSH terms): “Huntington’s disease,” “Huntington’s chorea,” “mood disorder(s),” “affect,” “anxiety disorder(s),” “obsessive behavior,” “compulsive behavior,” “schizophrenia and disorders with psychotic features,” “psychosis,” “thought disorder,” “dissociative disorder(s),” “neurotic disorder(s),” “neurosis,” “impulse control disorder(s),” “impulsive behavior,” “irritable mood,” “apathy,” “behavioral symptoms,” “behavior disorder(s)” and “personality disorder(s).” Animal studies and studies on pathophysiology were excluded and the language was limited to English. The references of the resulting articles were hand-searched for further relevant literature. This search resulted in 134 articles, including 59 articles describing original research, 29 review articles, 25 articles on psychopharmacological treatment, 19 case reports/series, and two editorials.

In order to estimate the cumulative prevalences and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of psychopathological phenomena, the 59 articles on original research were further selected for meeting the following conclusive set of criteria: 1) the study was original and measured the prevalence of psychopathology in a motor-symptomatic Huntington’s disease population; 2) the study applied standardized instruments with defined validity and reliability; and 3) the study used samples with verified CAG repeat expansions, which implied publication after 1993 when the Huntington’s disease mutation was identified. Calculation of 95% CI was carried out by means of the SPSS for Windows, release 12.0.1.

RESULTS

A total of seven original articles met the final set of strict criteria ( Table 1 ). The other 52 articles were excluded for the following reasons: 22 articles did not cover research on the prevalence of psychopathology; one article only concerned alcohol abuse; one exclusively concerned sexual abuse; and seven others concerned suicide/suicidal behavior. In three studies, solely premotor-symptomatic subjects were included, and in five studies subjects were offspring of Huntington’s disease gene carriers and had not been genetically verified. One article was excluded because only patients in a nursing home were examined. Of the remaining articles, 10 did not mention standardized instruments with defined validity and reliability and, in two articles, subjects were clinically suspected for Huntington’s disease, but CAG repeat numbers were not verified.

|

The remaining seven articles employed the following instruments for the assessment of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms: the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), 17 , 18 the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-III (SCID), 19 the behavioral section of the Unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS), 20 , 21 the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Symptom (Y-BOCS) scale, 22 and the more recently developed Problem Behavior Assessment Scale for Huntington’s Disease (PBA-HD), 23 which rates severity and frequency of behavioral problems in Huntington’s disease.

A broad range of symptoms portraying a chronically progressive course and fluctuating clinical picture are reported as neuropsychiatric features of Huntington’s disease. These neuropsychiatric phenomena are denoted by an array of terms, for example: behavioral problems or symptoms, personality changes, and psychiatric problems or disorders. The characteristic behavioral changes in early stage Huntington’s disease, including depression, irritability, mental inflexibility, and apathy, have in earlier days been described as “choreopathy.” 24 We have limited our subsequent analyses to the most frequently reported symptoms of depressed mood, anxiety, irritability, apathy, obsessive and compulsive symptoms, and psychosis. Originally, we intended to estimate the cumulative prevalences of the different neuropsychiatric phenomena. In spite of our strict inclusion criteria, however, large inconsistencies in methodology remained. This would lead to neither reliable nor valid results; studies used different assessment methods with strongly varying definitions of neuropsychiatric phenomena. For example, the definition of depression is much stricter according to the SCID 25 than to the UHDRS 26 Also, out of two studies using the same neuropsychiatric assessment measure in populations of comparable disease duration and cognitive functioning, one study 17 consistently reported lower prevalences than the other 18 This suggests a strong bias. Furthermore, the criteria for the onset of Huntington’s disease are not always given, the comparability of reported disease durations is highly questionable, and finally, not all populations are well-described. We therefore assumed them to be outpatients unless otherwise noted.

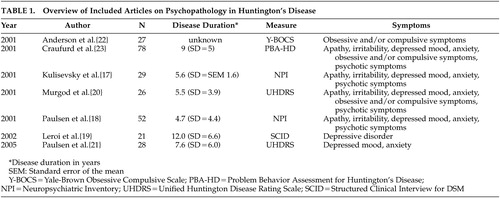

Depressed Mood

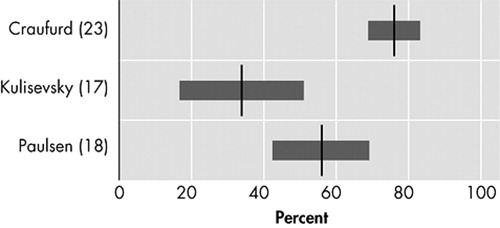

Six original studies investigate the prevalence of depressed mood in motor symptomatic patients. 17 – 21 , 23 Though two studies used the UHDRS to assess the prevalence of “low mood,” 20 , 21 and two others used the NPI, 17 , 18 results vary strongly, from 33% to 69% ( Figure 1 ). The only study using formal DSM criteria reports a prevalence of 43% for mood disorders: 29% for major depression and 14% for nonmajor depression. 19

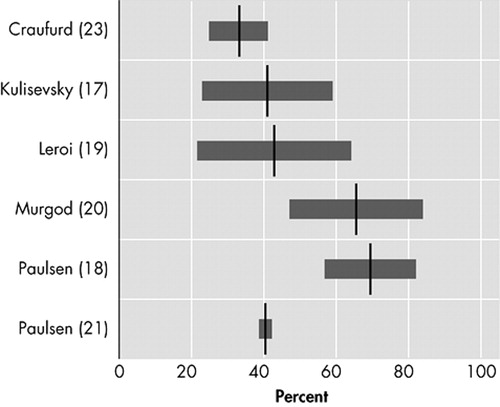

Anxiety

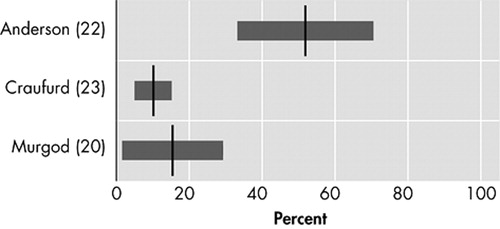

Five studies assess the prevalence of anxiety ( Figure 2 ). 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 23 The lowest prevalence (34%) was reported with the NPI. 17 The prevalence almost doubled (61%) in a small study, using the UHDRS, in 26 Huntington’s disease patients at their first hospital visit because of manifesting motor symptoms. 20

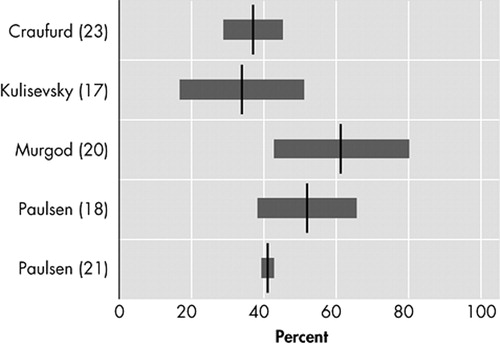

Irritability

Irritability, varying in description from “difficult to get along with” to “aggression,” is characterized by a reduction in control over temper that may result in verbal or behavioral outbursts. 27 In four original studies that assessed irritability as a separate behavioral phenomenon in Huntington’s disease, prevalences varied between 38% and 73% ( Figure 3 ). 17 , 18 , 20 , 23

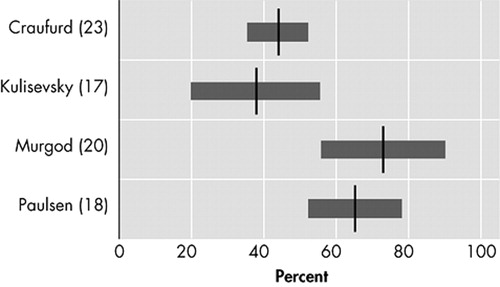

Apathy

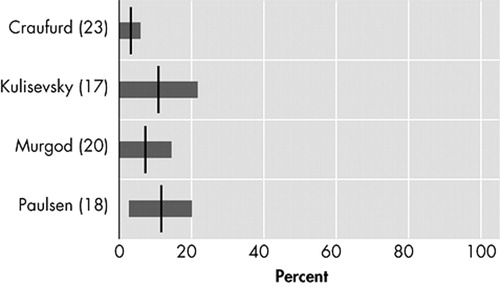

Apathy, characterized by reduced energy and activity, lack of drive, and impaired performance of everyday tasks, may be a separate clinical entity distinct from depression, especially in neuropsychiatric disorders. 28 , 29 In three original studies, prevalences of apathy in Huntington’s disease patients varied from 34% to 76% ( Figure 4 ). 17 , 18 , 23 Using the PBA, a cluster of symptoms reflecting apathy syndrome was found, with “loss of energy” (88%), “impaired performance of everyday life” (76%), and “lack of initiative” (76%) as the most prevalent behavioral abnormalities. 23

Obsessive and Compulsive Symptoms

The three studies investigating obsessive or compulsive behavior ( Figure 5 ) reported prevalences of 10% to 52%. 20 , 22 , 23 Out of 27 Huntington’s disease patients visiting an outpatient clinic, 52% scored either on compulsions or obsessions on the Y-BOCS. 22 The prevalence of obsessive symptoms was twice that of compulsive symptoms, while all patients with compulsive symptoms also had obsessive symptoms. Only two out of the 27 patients fulfilled formal DSM criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder. The two remaining studies reported lower prevalences in larger study populations 20 , 23

Psychotic Symptoms

Prevalences of psychotic symptoms varied between 3% and 11% in four studies. 17 , 18 , 20 , 23 Because of small sample sizes, three of the four studies report 95% confidence intervals that include a prevalence of 0% ( Figure 6 ). 17 , 20 , 23

DISCUSSION

These results confirm that behavioral problems and psychiatric disorders are major constituents of the clinical spectrum of Huntington’s disease. This is an important finding because these neuropsychiatric symptoms have a substantial impact on daily functioning, 12 possibly even more so than motor and cognitive dysfunctions 13 Nevertheless, more and better designed studies are necessary.

The studies up to date use a variety of assessment methods in Huntington’s disease populations of different disease stages. This ensures that their results are impossible to compare and that reliable prevalence estimates cannot be made. Definitions of neuropsychiatric phenomena are often unclear, and differences in definition can strongly influence the prevalences found. For example, in the UHDRS only one item refers to “low mood,” whereas the SCID uses the stringent DSM criteria for depression. These different methodologies limit the generalizability of the reported findings, which is further impaired by small sample sizes. Importantly, none of the seven studies found used a representative comparison group and, to our knowledge, no follow-up studies have been performed to relate the incidence of behavioral problems and psychiatric disorders to disease onset and disease progression.

Psychopathology

The prevalence of depressed mood in Huntington’s disease, varying from 33% to 69%, may be comparable to that of anxiety, irritability, and apathy. The development of depressive symptoms in Huntington’s disease could be a direct result of cerebral degeneration, for which several neuropathological mechanisms have been proposed. 30 , 31 Depression could, however, equally well be a psychological reaction to being at risk for Huntington’s disease, having grown up in an insecure and harmful environment, and/or the awareness of disease onset.

Many studies have found that depressive symptoms precede the onset of motor symptoms, 32 – 34 but no relation between the occurrence of depressive symptoms and disease duration has so far been reported. 35 Depression may, however, negatively correlate to cognitive decline, 23 which is possibly the result of concurrent decreasing illness awareness.

Anxiety has not been a main research interest in patients with Huntington’s disease. Nevertheless, “worrying,” which could be part of a generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), is often reported in Huntington’s disease patients, although it is mostly limited to worries about Huntington’s disease. 36 Since no studies were found that systematically investigate the prevalences of different anxiety disorders, this should be an important focus for future research.

Irritability without a prior history of short temper occurs in most Huntington’s disease patients, and seems to precede motor symptoms in gene carriers. 37 – 39 A tendency for irritability occurring more frequently in late-stage patients whose neurological symptoms have been present for 6 to 11 years has also been described. 23 This is confirmed by a cross-sectional observational study of 27 nursing home residents with Huntington’s disease (disease duration 7 to 11 years), which reports aggression in one-third of all patients over a 3-day period. 40 We contend that increasing degeneration of the striatum and the orbitofrontal-subcortical circuit in Huntington’s disease contributes to the development of socially inappropriate behavior, which initially may be manifested as subtle irritability and, in late-stage Huntington’s disease, as aggressive behavior. 41

Of all neuropsychiatric symptoms only apathy consistently appears to be positively related to disease progression. 23 , 42 , 43 Apathy is also strongly related to the decline of everyday functioning and, once present, tends to persist or worsen. 12 Damage to structures of the anterior cingulate-subcortical circuit has in particular been associated with motivational disorders, including apathy, 41 which may also be the case in Huntington’s disease. 44

The occurrence of obsessive and compulsive symptoms in Huntington’s disease is of particular interest because obsessive-compulsive disorder and Huntington’s disease possibly share a similar neuropathology of the basal ganglia and (orbito)frontostriatal circuits. 45 , 46 Many Huntington’s disease gene-carriers show personality changes with mental inflexibility in early stages, 23 possibly heralding future obsessive and compulsive symptoms. Though in certain families obsessive and compulsive symptoms have shown an early phenotype of Huntington’s disease, 45 they are not often identified as a manifestation of Huntington’s disease. 47

Psychotic symptoms usually occur when movement symptoms are already clearly manifest. This could explain why in earlier days, when Huntington’s disease was diagnosed at a later disease stage, psychosis was usually described as the main psychiatric feature of Huntington’s disease. 48 Even so, Huntington’s disease patients were often misdiagnosed with dementia praecox or schizophrenia until the first half of the 20th century. Nowadays, rather low prevalences (3% to 11%) of psychotic symptoms are reported, which is most probably due to earlier and better diagnoses of Huntington’s disease and a shift in research from inpatient to outpatient populations.

Recommendations for Future Research

The causal pathways leading to psychopathology in Huntington’s disease are unclear and should receive priority on the research agenda. Since Huntington’s disease families with multiple cases of schizophrenia and schizophreniform symptoms have been described, 49 , 50 as well as families with obsessive-compulsive disorders 45 and families with a high occurrence of affective syndromes in both gene carriers and noncarriers, 51 it is highly probable that other genes than the Huntington’s disease gene itself, as well as environmental factors, play a role in the development of psychopathology in Huntington’s disease. 52 Previous findings indeed suggest that both neuropathology and environmental stress contribute to the occurrence of neuropsychiatric phenomena in Huntington’s disease: a case series among 37 Huntington’s disease patients and 167 relatives reported significantly more psychiatric admissions and diagnoses in patients than in their relatives 53 Thus at least some psychopathology will be due to the etiology of Huntington’s disease, though not solely the Huntington’s disease gene. Since the same study showed that relatives of Huntington’s disease patients also had more psychiatric diagnoses and admissions than the general population, stressors such as growing up with an affected parent and with the uncertainty about one’s own disease status are also likely causes of psychopathology in Huntington’s disease.

To correct for environmental stress, prevalences of psychopathology in Huntington’s disease should be compared to healthy family members, particularly siblings of patients who do not carry the Huntington’s disease gene, since they share the same psychosocial family background as gene carriers. There is need for prospective research covering all different stages of Huntington’s disease with the use of such a comparison group, just as has been carried out before in premotor-symptomatic gene carriers. 37 , 39 Though this comparison group cannot correct for all potential biases affecting research in this difficult population (e.g., self-selection for genetic testing and difficulties with the staging of disease progression), use of the proposed comparison group will significantly increase the validity and interpretability of the test results. Also, a comparison of psychopathology in Huntington’s disease with other neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, could increase our understanding of the pathological mechanisms that affect the brain and behaviors of these patients. 17 , 54 , 55 Nevertheless, such a comparison should be explorative in nature as neither Huntington’s disease patients nor patients with Parkinson’s seem an adequate comparison group to the other.

As the Huntington’s disease gene does not have a full penetrance for developing specific behavioral problems or psychiatric disorders, research should also focus on the contribution of other biological factors, as well as environmental factors, to the behavioral phenotype of Huntington’s disease. Identification of endophenotypes, which do not depend on what is obvious to the unaided eye, could help to resolve questions about etiological models. 56 Such an endophenotype-based approach has the potential to assist in the genetic dissection of psychopathology. These endophenotypes should be researched on the level of neurobiology, neuropsychology, and neuroradiology. An example of a possible neurobiological endophenotype is disturbance of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis functioning with hypercortisolism; the stress hormone cortisol plays a major role in psychiatric disorders, particularly depressive disorders that have a high prevalence in Huntington’s disease. Disturbances in HPA-axis functioning have already been found in Huntington’s disease patients but have not yet been linked to behavioral or psychiatric morbidity in Huntington’s disease. 57 , 58 Another possible endophenotype is dysfunction of the immune system, 59 with altered secretion of cytokines. These have also been related to the presence of depression. 60 Vulnerability to psychopathology may be determined by genetic polymorphisms of the HPA-axis and the immune system, which is another important area of research in Huntington’s disease. 61

All future research should improve upon current methodologies. Some potential sources of current variation in test results, such as low incidence of Huntington’s disease with resulting small sample sizes and self-selection for testing and research, are difficult to avoid; researchers should be aware of this. Other sources of variety, mainly differences in methodology, can be eliminated if consensus on terminology and staging methods, as well as standardization of instruments are achieved. This is a necessary requirement for the comparability and generalizability of results. We propose that DSM criteria are used as the gold standard for psychiatric diagnosis, and standardized instruments for other neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy and irritability. For disease progression, we propose the motor section of the UHDRS. Although the motor score is not perfectly correlated with disease progression, a functional assessment with the Total Functional Capacity scale of the UHDRS, 62 which is related to disease progression, is not a good tool for this kind of research, as it is directly influenced by psychopathology. 63 , 64 Because the onset of Huntington’s disease is so gradual, disease duration is also not an adequate measure, and motor assessment is therefore the most objective, reliable, and comparable method of disease staging for research. Research should lead to an increased understanding and recognition of psychopathology in Huntington’s disease and its causes. This is essential for adequate treatment of those symptoms that could improve the overall functioning and quality of life of the Huntington’s disease patient and his or her direct environment.

1 . Morris M: Dementia and cognitive changes in Huntington’s disease. Adv Neurol 1995; 65:187–200Google Scholar

2 . Morris M: Psychiatric aspects of Huntington’s disease, in Huntington’s Disease. Edited by Harper PS. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1991, pp 81–126Google Scholar

3 . Cummings JL: Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms associated with Huntington’s disease, in Behavioral Neurology of Movement Disorders. Edited by: Weiner WJ, Lang AE. New York, Raven Press, 1995, pp 179–186Google Scholar

4 . Gusella JF, Wexler NS, Conneally PM, et al: A polymorphic DNA marker genetically linked to Huntington’s disease. Nature 1983; 306:234–238Google Scholar

5 . Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group: A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Cell 1993; 72:971–983Google Scholar

6 . Hoogeveen AT, Willemsen R, Meyer N, et al: Characterization and localization of the Huntington disease gene product. Hum Mol Genet 1993; 2:2069–2073Google Scholar

7 . Anderson KE: Huntington’s disease and related disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2005; 28:275–290Google Scholar

8 . Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, et al: Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature 2004; 431:805–810Google Scholar

9 . Cattaneo E, Zuccato C, Tartari M: Normal huntingtin function: an alternative approach to Huntington’s disease. Nat Neurosci 2005; 6:919–930Google Scholar

10 . Watt DC, Seller A: A clinico-genetic study of psychiatric disorder in Huntington’s chorea. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl 1993:23Google Scholar

11 . van Roon-Mom WMC, Hogg VM, Tippett LJ, et al: Aggregate distribution in frontal and motor cortex in Huntington’s disease brain. Clin Neurosci Neuropathol 2006; 17:667–670Google Scholar

12 . Hamilton JM, Salmon DP, Corey-Bloom J, et al: Behavioural abnormalities contribute to functional decline in Huntington’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74:120–122Google Scholar

13 . Wheelock VL, Tempkin T, Marder K, et al: Predictors of nursing home placement in Huntington disease. Neurology 2003; 60:998–1001Google Scholar

14 . Di Maio L, Squitieri F, Napolitano G, et al: Onset symptoms in 510 patients with Huntington’s disease. J Med Genet 1993; 30:289–292Google Scholar

15 . Witjes-Ané MNW, Vegter-van der Vlis M, van Vugt JPP, et al: Cognitive and motor functioning in gene carriers for Huntington’s disease: a baseline study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neuroscience 2003; 15:7–16Google Scholar

16 . Kirkwood SC, Siemers E, Hodes ME, et al: Subtle changes among presymptomatic carriers of the Huntington’s disease gene. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 69:773–779Google Scholar

17 . Kulisevsky J, Litvan I, Berthier ML, et al: Neuropsychiatric assessment of gilles de la tourette patients: comparative study with other hyperkinetic and hypokinetic movement disorders. Mov Disorders 2001; 16:1098–1104Google Scholar

18 . Paulsen JS, Ready RE, Hamilton JM, et al: Neuropsychiatric aspects of Huntington’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 71:310–314Google Scholar

19 . Leroi I, O’Hearn E, Marsh L, et al: Psychopathology in patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases: a comparison to Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1306–1314Google Scholar

20 . Murgod UA, Saleem Q, Anand A, et al: A clinical study of patients with genetically confirmed Huntington’s disease from India. J Neurol Sci 2001; 190:73–78Google Scholar

21 . Paulsen JS, Nehl C, Ferneyhough Hoth K, et al: Depression and stages of Huntington’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 17:496–502Google Scholar

22 . Anderson KE, Louis ED, Stern Y, et al: Cognitive correlates of obsessive and compulsive symptoms in Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:799–801Google Scholar

23 . Craufurd D, Thompson JC, Snowden JS: Behavioural changes in Huntington’s disease. NNBN 2001; 14:219–226Google Scholar

24 . Kehrer F: Erblichkeit und Nervenleiden. Ursachen und Erblichkeitskreis von Chorea, Myoklonie und Athetose, in: Monographien aus dem Gesamtgebiete der Neurologie und Psychiatrie, Berlin, Springer, 1928Google Scholar

25 . Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, et al: The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R. I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Google Scholar

26 . Huntington Study Group: Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale: reliability and consistency. Mov Disorders 1996;11:136–142Google Scholar

27 . Snaith RP, Taylor CM: Irritability: definition, assessment and associated factors. Br J Psychiatry 1985; 147:127–136Google Scholar

28 . Levy ML, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA, et al: Apathy is not depression. J Neuropsychiatry 1998; 10:314–319Google Scholar

29 . Marin RS: Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:243–254Google Scholar

30 . Slaughter JR, Martens MP, Slaughter KA: Depression and Huntington’s disease: prevalence, clinical manifestations, aetiology, and treatment. CNS Spectr 2001; 6:306–326Google Scholar

31 . Peyser CE, Folstein SE: Huntington’s disease as a model for mood disorders. clues from neuropathology and neurochemistry. Mol Chem Neuropathol 1990; 12:99–119Google Scholar

32 . Folstein SE, Franz ML, Jensen BA, et al: Conduct disorder and affective disorder among the offspring of patients with Huntington’s disease. Psychol Med 1983; 13:45–52Google Scholar

33 . Shiwach R: Psychopathology in Huntington’s disease patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90:241–246Google Scholar

34 . Tibben A, Duivenvoorden HJ, Niermeijer MF, et al: Psychological effects of presymptomatic DNA testing for Huntington’s disease in the Dutch program. Psychosom Med 1994; 56:526–532Google Scholar

35 . Zappacosta B, Monza D, Meoni C, et al: Psychiatric symptoms do not correlate with cognitive decline, motor symptoms, or CAG repeat length in Huntington’s disease. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:493–497Google Scholar

36 . Pflanz S, Besson JAO, Ebmeier KP, et al: The clinical manifestation of mental disorder in Huntington’s disease: a retrospective case record study of disease progression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 83:53–60Google Scholar

37 . Kirkwood SC, Siemers E, Viken R, et al: Longitudinal personality changes among presymptomatic Huntington’s disease gene carriers. NNBN 2002; 15:192–197Google Scholar

38 . Berrios GE, Wagle AC, Marková IS, et al: Psychiatric symptoms and CAG repeats in neurologically asymptomatic Huntington’s disease gene carriers. Psychiatry Res 2001; 102:217–225Google Scholar

39 . Witjes-Ané MNW, Zwinderman AH, Tibben A, et al: Behavioural complaints in participants who underwent predictive testing for Huntington’s disease. J Med Genet 2002; 39:857–862Google Scholar

40 . Shiwach RS, Patel V: Aggressive behaviour in Huntington’s disease: a cross-sectional study in a nursing home population. Behav Neurol 1993; 6:43–47Google Scholar

41 . Mega MS, Cummings JL: Frontal-subcortical circuits and neuropsychiatric disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:358–370Google Scholar

42 . Caine ED, Shoulson I: Psychiatric syndromes in Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:728–733Google Scholar

43 . Burns A, Folstein S, Brandt J, et al: Clinical assessment of irritability, aggression, and apathy in Huntington and Alzheimer disease. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:20–26Google Scholar

44 . Aylward EH, Sparks BF, Field KM, et al: Onset and rate of striatal atrophy in preclinical Huntington disease. Neurol 2004; 63:66–72Google Scholar

45 . De Marchi N, Morris M, Mennella R, et al: Association of obsessive-compulsive disorders and pathological gambling with Huntington’s disease in an Italian pedigree: possible association with Huntington’s disease mutation. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 97:62–65Google Scholar

46 . Freire Maia ASS, Reis Barbosa E, Rossi Menezes P, et al: Relationship between obsessive-compulsive disorders and diseases affecting primarily the basal ganglia. Rev Hosp Clín Fac Med Sao Paulo 1999; 54:213–221Google Scholar

47 . De Marchi N, Mennella R: Huntington’s disease and its association with psychopathology. Harvard Rev Psychiatry 2000; 7:278–289Google Scholar

48 . Folstein SE, Folstein MF: Psychiatric features of Huntington’s disease: recent approaches and findings. Psychiatr Developments 1983; 2:193–206Google Scholar

49 . Lovestone S, Hodgson S, Sham P, et al: Familial psychiatric presentation of Huntington’s disease. J Med Genet 1996; 33:128–131Google Scholar

50 . Tsuang D, Almqvist EW, Lipe H, et al: Familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms in Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1955–1959Google Scholar

51 . Folstein S, Abbott MH, Chase GA, et al: The association of affective disorder with Huntington’s disease in a case series and in families. Psychol Med 1983; 13:537–542Google Scholar

52 . Rosenblatt A, Leroi I: Neuropsychiatry of Huntington’s disease and other basal ganglia disorders. Psychosomatics 2000; 41:24–30Google Scholar

53 . Jensen P, Sørensen SA, Fenger K, et al: A study of psychiatric morbidity in patients with Huntington’s disease, their relatives, and controls; admissions to psychiatric hospitals in Denmark from 1969 to 1991. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:790–797Google Scholar

54 . Freire Maia ASS, Reis Barbosa E, Rossi Menezes P, et al: Relationship between obsessive-compulsive disorders and diseases affecting primarily the basal ganglia. Rev Hosp Clín Fac Med S Paulo 1999; 54:213–221Google Scholar

55 . Hague SM, Klaffke S, Bandmann O: Neurodegenerative disorders: Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005; 76:1058–1063Google Scholar

56 . Gottesman II, Gould TD: The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: etymology and strategic intentions. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:636–645Google Scholar

57 . Kurlan R, Caine E, Rubin A, et al: Cerebrospinal fluid correlates of depression in Huntington’s disease. Arch Neurol 1988; 45:881–883Google Scholar

58 . Heuser JE, Chase TH, Mouradian MM: The limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in Huntington’s disease. Biol Psychiatry 1991; 30:943–952Google Scholar

59 . Leblhuber F, Walli J, Jellinger K, et al: Activated immune system in patients with Huntington’s disease. Chem Lab Med 1998; 36:747–750Google Scholar

60 . Penninx BWJH, Kritchevsky SB, Yaffe K, et al: Inflammatory markers and depressed mood in older persons: results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:566–572Google Scholar

61 . Hunter DJ: Genetic-environment interactions in human diseases. Nature 2005; 6:287–298Google Scholar

62 . Shoulson I, Fahn S: Huntington’s disease: clinical care and evaluation. Neurology 1979; 29:1–3Google Scholar

63 . Hamilton JM, Salmon DP, Corey-Bloom J, et al: Behavioural abnormalities contribute to functional decline in Huntington’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74:120–122Google Scholar

64 . Nehl C, Paulsen JS, and The Huntington Study Group: Cognitive and psychiatric aspects of Huntington disease contribute to functional capacity. J Nerv Mental Dis 2004;192:72–74Google Scholar