Relationship of Cognitive and Functional Impairment to Depressive Features in Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias

Abstract

Patients with clinical diagnoses of Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, or undifferentiated dementia were rated on standardized measures of depression, cognitive impairment, and functional impairment. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the relationship between functional or cognitive impairment, as well as their interaction, and depressive features in each group. This analysis revealed notable differences by type of dementia. The results imply that the mechanisms underlying depression in Alzheimer's disease may be different from those in vascular and other types of dementia. These results also provide indicators to the clinician for further evaluation of depression in different dementia subtypes.

Many patients with dementia have concomitant behavioral/mental disturbances. These include psychiatric symptoms such as depressive features, delusions, and hallucinations, as well as behavioral disturbances such as wandering, aggression, and disinhibition. These disturbances lead to much of the morbidity associated with dementia, and they affect both the victims of dementia and their caregivers. Estimates of the prevalence of depressive features among patients with Alzheimer's disease range from 0%1 to 86%,2 with most estimates in the 20% to 25% range.3–5 In a recent study from our group,6 a diagnosis of Major Depressive Episode (as defined by the DSM-III-R7 ) could be made in 22% of patients with probable Alzheimer's disease8 and a diagnosis of Minor Depressive Episode (DSM-IV research criteria9) could be made in 27%. The variance in the reported estimates of depressive features in dementia is most likely due to differences in patient populations, diagnostic criteria, and assessment methods for both dementia and depressive features, as well as to similarities in signs and symptoms between depressive features and dementia.10

Cognitive and functional impairment are central to dementia and might be expected to be associated with occurrence of depressive features. However, the relationship between severity of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms is unclear. In fact, studies have found depressive symptoms associated with less severe dementia11,12 and with more severe dementia,13,14 as well as no association at all.10,15 The relationship between depressive features and functional impairment in dementia has been explored in a few studies, all of which found that patients with depressive features were more functionally impaired.3,6,14,16,17 In addition to studying different populations of patients, these studies differed in the assessment instruments used to define depressive features. For example, some studies used scores on particular depression scales, usually observer-rated ones such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D),10 and others used DSM-III-R criteria for major depression, as assessed by a psychiatric evaluation.11

One issue that has not been adequately examined is a possible interaction between cognitive and functional impairment in their association with depressive features in dementia patients. For example, are patients who are more cognitively impaired more or less likely to be depressed if they are also functionally impaired? Can the level of cognitive and functional impairment in a demented person be used to predict the likelihood of depressive features? And is the relationship between depressive features and cognitive or functional impairment specific to the syndrome of dementia, or does it depend on the cause of the dementia, such as Alzheimer's or cerebrovascular disease?

These questions are important, since their answers might lead to a better understanding of the causes and presentation of depressive features in dementia. In addition, if there is an interaction between cognitive and functional impairment and the likelihood of depressive features in dementia, physicians might use information about cognition and functioning to decide which patients require further investigation for depressive features. An interaction between type of dementia and the association of cognition or function with depressive features would also imply underlying differences in the pathophysiology of depressive features in different types of dementia. Studies of depressive features in dementia of different etiologies are rare, as are comparisons of depressive features accompanying functional versus cognitive deficits in dementia.

We present results of a study of depressive features in a large series of dementia outpatients with diverse etiologies for dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, cerebrovascular disease, and other causes. We sought to clarify the relationship between depressive features and functional or cognitive impairment, individually as well as in combination, across the different types of dementia. We used specific, well-defined scales to measure depressive features, cognitive impairment, and functional impairment.

METHODS

Subjects

A total of 569 patients serially referred to the Johns Hopkins Neuropsychiatry and Memory Group (NMG) for dementia assessment and treatment were evaluated between February 1994 and July 1996 at one of two clinic sites: the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland (48%), or Copper Ridge in Sykesville, Maryland (51%). All data were collected on each patient's first evaluation as part of routine clinical practice. Patients were excluded from the study if 1) they did not have a primary diagnosis of dementia or 2) data were unavailable on them for one of the parameters included in the study. Thus, a total of 259 patients with dementia by DSM-IV criteria were included in the study. The mean age of the patients was 76.0 years (SD=9.8), 69% were women, and 84% were Caucasian. Eighty-eight percent of the patients were currently married or widowed, and only 4% had never been married. Approximately 92% were living in their own or a family member's home; the rest resided in assisted living settings. Seventy-three percent had their general health rated as fair or good. The most common chief complaint bringing the patient to the NMG was “diagnosis of dementia” (49%). Psychiatric symptoms brought 32% to the NMG, and behavioral problems and family management issues each were chief complaints for 10% of the patients.

Assessment

Each patient underwent an extensive neuropsychiatric examination as previously described.18 A comprehensive history, neurological examination, and mental status examination were performed by experienced geriatric psychiatrists. Brain imaging (MRI or CT) and laboratory assessment (including chemistries, electrolytes, complete blood count, liver tests, thyroid tests, serum B12, serum folate, sedimentation rate, rapid plasma reagin for syphilis, urinalysis, ECG, and chest X-ray) were performed as deemed necessary. Diagnoses were made using the information obtained above, along with information from family members, other caregivers, and primary care physicians, which was used to ensure reliability.19 Patients were also rated on the following scales:

Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD).20 This is an observer-rated scale designed to measure depressive symptoms in dementia, which has high reliability and validity for standardized psychiatric diagnosis.20 Nineteen depressive symptoms were rated for presence in the past one week on a scale of 0 to 2, with 0 standing for absent, 1 for mild or intermittently present, and 2 for severe or frequently present. Scores on the CSDD are highly correlated with scores on the Ham-D.21 For the purposes of this study, patients with a score >12 were defined as being depressed, since scores >12 on the CSDD are strongly correlated with a psychiatric diagnosis of a major depressive episode.6,20

Psychogeriatric Dependency Rating Scale,22physical dependency subscale (PGDRS-P). This subscale of the PGDRS was used to quantify physical dependency as reflected in impaired performance of activities of daily living (ADL). Impairment in hearing, vision, mobility, speech, dressing, hygiene, toileting, and feeding was rated for the past week, with higher scores in each category reflecting greater dependency in self-care. For the purposes of this study, a score of 0 was considered no impairment, 1–6 mild impairment, and >6 moderate to severe impairment in functional abilities.

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).23 This is a cognitive test designed to assess orientation to place and time, memory, attention, concentration, language, praxis, and visuospatial skills. Although the MMSE was originally designed to test mental status, decreased scores are associated with dementia.23 The MMSE is a 30-point scale, and for the purposes of this study (as is common practice) a score >18 was considered mild or no impairment, 10–18 moderate impairment, and 0–9 severe impairment.

Presumptive Cause of Dementia

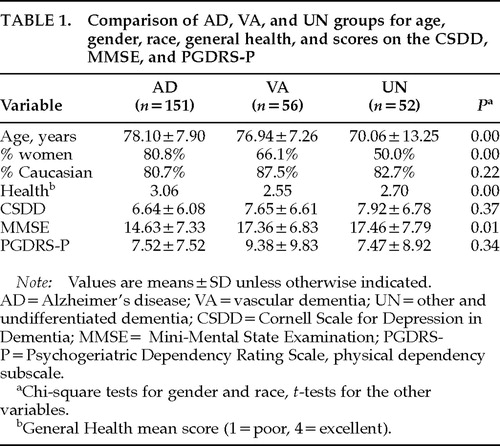

Each of the 259 patients was placed in one of three groups on the basis of primary diagnosis, which followed an extensive neuropsychiatric examination and was based on widely accepted criteria. The three groups were as follows: 1) possible and probable Alzheimer's disease (AD), based on the NINCDS/ADRDA criteria,8 151 patients; 2) vascular dementia (VA), based on the criteria of the NINDS/AIREN,24 56 patients; 3) other and undifferentiated dementia (UN), 52 patients. This subgroup contained cases of “atypical” dementia, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal degeneration, and anoxic/hypoxic dementia. As can be seen in Table 1, these groups were not statistically different from each other for race, but they were for gender and age. The dementia groups were also statistically different from each other on a measure of General Health (1=poor, 2=fair, 3=good, 4=excellent), with the AD group significantly different from both the AD and UN groups. However, these groups were not statistically different from each other in the rate of severe depressive features (as defined by a CSDD score >12).

Analyses

All analyses were performed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version for Windows. The prevalence of severe depressive features (as defined by a CSDD score >12) by MMSE and PGDRS-P subgroups is reported for each clinical group separately. Logistic regression, with depressive features (CSDD >12) as the dependent variable, was then used to assess the effect of MMSE and/or PGDRS-P score (used as continuous variables) on depressive features in each group. Odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals for each variable in these regressions were computed and are reported. In addition, taking data from all 259 patients, a logistic regression was performed to assess the effect of diagnosis on depressive features.

RESULTS

The prevalence of depressive features, as defined by a score >12 on the CSDD, in each of the groups was as follows: AD 17%, VA 19%, UN 22%. These rates were not different statistically (χ2=3.75, df=4, P=0.44).

Table 1displays the means and standard deviations of scores on the CSDD, MMSE, and PGDRS-P for each group. When compared on the CSDD scores, the three dementia groups were not significantly different (F=1.01, P=0.37), and there were no significant differences on the PGDRS-P (F=1.09, P=0.34). The AD group had, on average, lower MMSE scores (F=4.42, P=0.01).

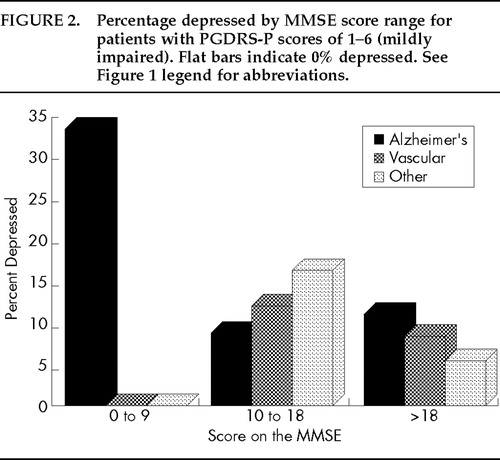

Figures 1–3 display the percentage of depressed patients for each of the three dementia groups by MMSE (x axis of each graph) and PGDRS-P scores. Figure 1 displays data for those with PGDRS-P scores of 0 (no impairment), Figure 2 for PGDRS-P scores of 1–6 (mild impairment), and Figure 3 for scores >6 (moderate to severe impairment).

The prevalence of depressive features among Alzheimer's patients ranged from 0% to 64% depending on degree of cognitive and functional impairment. In the absence of ADL impairment (Figure 1), depressive features afflicted only those with higher MMSEs (17% depressed). However, in the presence of mild ADL impairment (Figure 2), AD patients with low MMSEs were most likely to be depressed (34%) and those with higher MMSE scores were less likely to be depressed (10%–14%). In the presence of moderate to severe ADL impairment (Figure 3), AD patients with higher MMSE scores were very often depressed (68%) and those with lower MMSE scores were less likely to be depressed (9%–31%). These results suggest that depressive features in AD were most common among patients whose severity levels of cognitive and functional impairment were not proportionate (that is, among those with greater ADL impairment and less cognitive impairment or vice versa), but these features were typically in the 15% to 20% range in other instances. In vascular dementia, the distribution of depressive features was different, ranging from 42% for those with severe cognitive impairment and moderate/severe ADL impairment to 0% for other groups. The UN group all had at least a small prevalence of depressive features, ranging from 8% to 61%, and distributed as seen in Figures 1, 2, and 3.

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regressions with depressive features (CSDD scores >12) as the dependent variable and total MMSE and/or PGDRS-P scores as the covariates. Both unadjusted odds ratios (for either MMSE or PGDRS-P), with lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence interval, and adjusted odds ratios (including both the MMSE and PGDRS-P scores in the model) are included in Table 2. The odds ratios are best interpreted as the change in risk of depressive features for each point of change in MMSE or PGDRS-P. The upper and lower limits delineate the 95% confidence interval for the OR point estimate. If this confidence interval crosses 1, then the OR estimate is not statistically significant.

For the AD group, a 1-point increase in PGDRS-P was associated with an OR of 1.04 (or a mean 4% increase in depressive features prevalence for each point increase in PGDRS-P) as a risk for depressive features. However, the relevant confidence interval crossed 1, and thus this risk was not statistically significant. When MMSE was included in the model, the adjusted OR became 1.09, and the confidence interval indicates statistical significance, suggesting a 9% increase in risk of depressive features for each point increase in PGDRS-P (a 45% increase for a 5-point increase, since 5×9=45). Similarly, after adjustment for PGDRS-P, increases in MMSE score for the AD group carried increased risk for depressive features. Note that higher scores on the MMSE imply less severe cognitive impairment, whereas higher scores on the PGDRS-P imply more functional impairment. The only other significant OR for depressive features risk was in the UN dementia group, where higher scores on the PGDRS-P were associated with increased risk for depression, both alone and after adjustment for MMSE scores. Thus, the relationship between cognitive impairment, functional impairment, and risk of depressive features depended on diagnosis: for AD, both variables affected depressive features risk, whereas in VA neither variable was associated with depressive features. In the UN dementia group, only the PGDRS-P score was associated with depressive features, both alone and when adjusted for MMSE score. When interaction terms were included in these regression models they did not greatly affect the model variance, and the interaction terms themselves were not statistically significant.

The effect of diagnosis on the rate of severe depressive features was then examined in a logistic regression for the entire group of 259 patients, with severe depressive features (CSDD >12) as the dependent variable and diagnosis as the covariate. The results of this analysis were nonsignificant, with an OR of 1.15, lower limit of 0.76, and upper limit of 1.54.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the relationship between cognitive impairment, functional impairment, and risk of depressive features in 259 dementia outpatients. There are several limitations to our study. First, the population that we studied is, in general, healthier than the general dementia population given that 92% live in their own or their families' homes. Thus, some of our findings may not be applicable to the nursing home population of demented patients. Another limitation is the possibility that some of the patients designated as either AD or VA may in fact have had a combined diagnosis of AD and VA, since it has been reported that both may occur in 10% to 20% of demented patients. In addition, the UN group of patients was clinically heterogeneous, with diagnoses ranging from Lewy body dementia to frontotemporal degeneration to anoxic/hypoxic dementia. Therefore the findings regarding this particular group of patients may not apply well to individual patients. Finally, all diagnoses made in this series were clinical diagnoses and were not confirmed by autopsy. This limitation, however, makes the study in fact more practical in applicability to the clinical setting.

There are also several statistical limitations to this study. We looked at the rate of severe depressive features as defined by a CSDD score >12 and not the effect of cognitive and physical impairment on the range of CSDD scores in general. We were mainly interested in the effect of cognitive and physical impairment in clearly depressed demented individuals, since many of the signs and symptoms of dementia may overlap some depressive features. We felt that this potential overlap could best be addressed by limiting the study to the effect on severe depressive features, or CSDD >12. We performed logistic regressions within each dementia group and have looked at differences between all the groups within this report. The reader is cautioned that some of the differences seen could be secondary to other differences between the groups, such as group size, general health differences, or MMSE scores.

The rates of moderate to severe depressive features across different clinical types of dementia ranged from 17% to 22%, which is in agreement with previous work from our group,6 as well as other studies.3–5 The three dementia groups did not differ significantly from each other by CSDD scores or by PGDRS-P scores. However, they did differ by MMSE scores, the AD group having a lower MMSE score than the other two groups. There were also differences in general health scores, the AD group being statistically different from both the VA and UN groups. However, and perhaps most important, there was no effect of diagnosis on the rate of severe depression when the group was analyzed as a whole. Thus, the differences between the different dementia groups cannot be attributed to differences in rates of severe depressive symptoms between the groups.

These findings indicate that there is a complex relationship between type of dementia, severity of cognitive or functional impairment, and risk of depressive features, which probably explains in part the great variance in reported prevalences of depressive features in dementia (0%–86%). Alzheimer's disease patients with less severe cognitive impairment or more severe functional impairment had a higher risk for depressive features. In fact, two-thirds of the AD patients with MMSE scores >18 and PGDRS-P scores >6 were depressed. The UN dementia group also had a positive association between functional impairment and risk for depressive features; this association remained even after adjustment for degree of cognitive impairment. However, cognitive impairment, either alone or adjusted for functional impairment, was not associated with risk for depressive features in the UN group. In sharp contrast to both the AD and UN groups, in the VA group there was no clear relationship between functional or cognitive impairment and risk for depressive features.

These results imply that the mechanisms underlying depressive features in Alzheimer's disease may be different from those underlying depressive features in other types of dementia. Alzheimer's disease may lead to depressive features in its early stages. Given that several studies have shown that AD patients with depressive features have lower neuronal counts in the locus ceruleus,25–27 leading to lower brain levels of norepinephrine, which is a putative etiology for major depression,28 perhaps norepinephrine is lowered in at least some Alzheimer patients' brains early in the course of the disease. Further, depressive features in AD have been associated with a family history of mood disorder,18,21 lending support to a neurochemical basis for the depressive features in AD.

The lack of association between depressive features and cognitive impairment in vascular dementia may be explained by their association with stroke in specific areas of the brain, namely the left frontal lobe, the thalamus, or the caudate. Cognitive deficits in VA are a function of both the location and the amount of brain tissue affected—hence the name multi-infarct dementia and the characteristic stepwise progression as more strokes add to the dementia. However, depressive features appear to occur equally at all stages of VA, suggesting that its development is not a consequence of additive tissue loss, but rather the result of involvement of particular areas of the brain by the cerebrovascular process.

Patients in the UN dementia group (a more heterogeneous group) showed no association between cognitive impairment and depressive features. This further supports the argument that depressive features in dementia occur when particular areas of the brain are affected by the underlying disease. It is reasonable to postulate that when one or more particular areas of brain, such as the left frontal lobe, the thalamus, the caudate, or the locus ceruleus, become affected by any dementing illness (including Alzheimer's disease) patients have a higher risk of developing depressive features. The only difference between dementia groups in relationship to depressive features would be a difference in which brain area becomes affected so as to lead to depressive features (this would be different for AD, VA, and others) and when in the course of disease this area becomes affected. Thus, in Alzheimer's disease the locus ceruleus may specifically be affected early in the course of the disease process, whereas depressive features in the other dementia subtypes may be related to a more random process, depending on when and if particular areas of brain are affected. The lack of association, across all dementia types, between depressive features and more severe cognitive impairment strongly argues against the theory that depressive features represent a psychological reaction to the severity of cognitive impairment.

Another finding in our study is that patients with AD who are less severely demented but more functionally impaired are more likely to be depressed. One explanation for this finding is that since patients with less severe cognitive impairment are usually less functionally impaired, greater functional impairment in a mildly demented patient might indicate that a process other than dementia is leading to the functional impairment. This might be a physical disability such as blindness or difficulty in walking, but it could also be the coexisting depressive features. Indeed, the literature consistently indicates that depressive features in dementia are associated with a greater degree of functional impairment3,6,14–17 attributable to the depressive syndrome itself. Alternatively, difficulties with activities of daily living might be more likely to cause early dementia patients to feel depressed. Similar to the AD group, the UN group had a strong association between functional impairment and depressive features. This decline in functional ability in the depressed UN patients can also be viewed as either the result of the depressive features or the cause of the depressive features. Our own data suggest the former. An interesting question that remains to be answered is whether or not treatment of depressive features in these patients will allow a recovery of function such that the PGDRS-P score will decline. Further study of this issue would allow discrimination between these two hypotheses.

These findings have implications for the diagnosis of depressive features in dementia patients. Given the consistently elevated prevalence of depressive features across all three dementia groups, all patients with dementia should undergo regular evaluations for depressive features. AD patients and patients who fall into the UN category, such as patients with Lewy body dementia or subcortical dementia, may have particular “red flags” for likelihood of depressive features that should trigger a more extensive investigation. Thus, AD patients who are less severely cognitively impaired (MMSE >18) or patients with AD or UN dementia who have significant functional impairment, particularly if this is disproportionate to the degree of cognitive impairment, should undergo a thorough investigation for depressive features. Such clinical “triggers” for evaluation may lead to improved diagnosis and treatment for depressive features in dementia and ultimately a better quality of life for the patients and their caregivers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health Grant 1R01 56511.

FIGURE 1. Percentage depressed by MMSE score range for patients with PGDRS-P scores of zero (unimpaired). Flat bars indicate 0% depressed. No unimpaired patients had MMSE scores in the 0–9 range. MMSE=Mini-Mental State Examination; PGDRS-P=Psychogeriatric Dependency Rating Scale, physical dependency subscale.

FIGURE 2. Percentage depressed by MMSE score range for patients with PGDRS-P scores of 1–6 (mildly impaired). Flat bars indicate 0% depressed. See Figure 1 legend for abbreviations.

FIGURE 3. Percentage depressed by MMSE score range for patients with PGDRS-P scores >6 (moderately or more impaired). Flat bars indicate 0% depressed. See Figure 1 legend for abbreviations.

|

|

1. Knesevich JW, Martin RL, Berg L, et al: Preliminary report on affective symptoms in early stages of senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:350–353Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Merrian A, Aronson M, Gaston P, et al: The psychiatric symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988; 26:7–12Google Scholar

3. Rovner BW, Broadhead J, Spencer M, et al: Depression and Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:350–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Migliorelli R, Teson A, Sabe S, et al: Prevalence and correlates of dysthymia and major depression among patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:37–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Teri L, Wagner A: Alzheimer's disease and depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:379–391Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lyketsos CG, Steele C, Baker L, et al: Major and minor depression in Alzheimer's disease: prevalence and impact. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 9:556–561Link, Google Scholar

7. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

8. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–949Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

10. Lazarus LW, Newton N, Cohler B, et al: Frequency and presentation of depressive symptoms in patients with primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:41–45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Burnes A, Jacoby R, Levy R: Psychiatric phenomena in Alzheimer's disease. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:72–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Lopez OL, Boller F, Becker JT, et al: Alzheimer's disease and depression: neuropsychological impairment and progression of the illness. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:855–860Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Devanand DP, Miller L, Richards M, et al: The Columbia University Scale for Psychopathology in Alzheimer's Disease. Arch Neurol 1990; 49:371–376Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Haupt M, Kurz A, Greifenhagen A: Depression in Alzheimer's disease: phenomenological features and association with severity and progression of cognitive and functional impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1995; 10:469–476Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Cummings JL, Miller B, Hill MA, et al: Neuropsychiatric aspects of multi-infarct dementia and dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol 1987; 44:389–393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Pearson JL, Teri L, Reifler BV, et al: Functional status and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer patients with and without depression. J Am Geriatr Soc 1989; 37:1117–1121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Fitz AG, Teri L: Depression, cognition, and functional ability in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42:186–191Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lyketsos CG, Tune L, Pearlson G, et al: Major depression in Alzheimer's disease: an interaction between gender and family history. Psychosomatics 1996; 37:380–384Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Teri L, Wagner A: Assessment of depression in patients with Alzheimer's disease: concordance among informants. Psychology and Aging 1991; 6:280–285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, et al: Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. Biol Psychiatry 1988; 23:271–284Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Pearlson GD, Ross CA, Lohr WD, et al: Association between family history of affective disorder and the depressive syndrome of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:452–456Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Wilkinson IM, Graham-White J: PGDRS: a method of assessment for use by nurses. Br J Psychiatry 1980; 137:558–565Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, Hughes PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Romain GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al: Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies, report of the NINDS-AIREN international workshop. Neurology 1993; 43:250–259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Zubenko GS, Moosy J, Kopp U: Neurochemical correlates of major depression in primary dementia. Arch Neurol 1990; 47:209–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Zweig RM, Ross CA, Hedreen JC: The neuropathology of aminergic nuclei in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 1988; 24:233–242Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Forstl H, Burns A, Luthert P: Clinical and neuropathological correlates of depression in Alzheimer's disease. Psychol Med 1992; 22:877–884Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Baldessarini RJ: Treatment of depression by altering monoamine metabolism: precursors and metabolic inhibitors. Psychopharmacol Bull 1984; 20:224–239Medline, Google Scholar