Predictive Factors for Outcome of Nonepileptic Seizures After Diagnosis

Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess prognosis among adult patients with nonepileptic seizures (NES) and to determine predictor variables for resolution of NES after diagnosis. Six to 9 months after receiving a video-EEG-documented diagnosis of NES, 43 adults responded by telephone interview to a detailed, structured questionnaire probing history of the episodes, psychiatric factors, socioeconomic variables, relationships, reactions to receiving the diagnosis, and potential history of litigation. At follow-up, only 18.6% were episode-free, 55.8% had improved, 16.3% reported no change, and 9.3% reported greater frequency of episodes. Patients who reported having many friends currently or having good relationships with friends as a child were significantly more likely to be episode-free. Subjects with pending litigation were significantly less likely to experience a reduction in episodes.

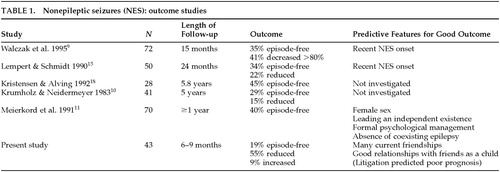

Nonepileptic seizures (NES; also known as pseudoseizures or psychogenic or hysterical seizures) are clinical events that resemble epileptic attacks but are unassociated with physiologic central nervous system dysfunction.1,2 Although an abundant literature3–8 focuses on the clinical distinctions between epileptic and nonepileptic seizures, relatively few studies have examined outcomes after the diagnosis of NES has been established (Table 1). Some investigations examined pediatric and adult patients together,9–11 despite suggestions that NES characteristics and prognoses may differ between these groups.12 The conclusions of some studies were limited by sample size,13 inclusion of patients with both epileptic and nonepileptic seizures9,10,13 and reliance on methods other than video-EEG to make the diagnosis of NES.14,15

Factors that may predict NES prognosis are age at onset and duration of NES disorder, psychiatric disorder, socioeconomic status, relationships with family and friends, sexual or physical abuse, reactions to receiving the diagnosis of NES, and litigation issues. Although a definitive study designed to examine predictive variables would require a large number of subjects, suggestions as to associations between specific factors and NES outcome may be apparent from limited surveys. We sought to examine outcomes among NES patients who were rigorously diagnosed and who did not have current epileptic seizures, as well as to examine specific variables that may predict outcome.

METHODS

Population

From January 1995 until June 1997, we identified patients over the age of 16 who were diagnosed with NES (pseudoseizures). The patients were referred by community neurologists for evaluation of uncontrolled seizures or episodes suspicious for NES. The NES diagnosis was based on a comprehensive neurological evaluation and video-EEG monitoring that captured characteristic episodes during the recording. Those episodes identified as NES were not associated with postictal prolactin elevations or with electroencephalographic seizure correlates and were clinically atypical for epileptic seizures.7,8 During the admission to the hospital or in a meeting held in the outpatient clinic following admission, the clinician reviewed the diagnosis of NES in a manner described by Shen et al.16 The discussion with the patient aimed to maintain patient dignity, stressing the concept of “the mind playing tricks on the body” and reassuring the patient that the clinician considered the disorder to be of equal importance to any other illness. We uniformly recommended further evaluation and treatment by a psychiatrist or psychotherapist. Most patients were treated by community neurologists and were returned to the care of the original healthcare provider. In most cases, we did not taper antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), to allow patients to focus on one intervention at a time and to emphasize psychiatric assistance as the first treatment modality.

We excluded patients who had 1) episodes suggestive of possible current epileptic seizures (e.g., patients with episodes associated with major injuries); 2) episodes associated with purely subjective phenomena (e.g., episodic numbness in the absence of altered awareness); 3) episodes captured on video-EEG that were not typical of the usual episodes described by the patient.

Testing

Six to 9 months after advising the patients of our NES diagnosis, we contacted patients who met study criteria. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained to administer a 40-item, structured, telephone-based interview that related to the time preceding the NES diagnosis, the time of diagnosis, and the time of current follow-up for the following items:

| • | 1. History of NES and epileptic seizures: These questions focused on age at onset of episodes, history of prior epileptic seizures (episodes that differed in nature from the current episodes, often supplemented by EEG evidence), age at time of NES diagnosis, and use of AEDs. In patients with prior epileptic seizures and current NES, we recorded only the age at onset of the former because it was difficult to sort out by history when NES replaced epileptic seizures. | ||||

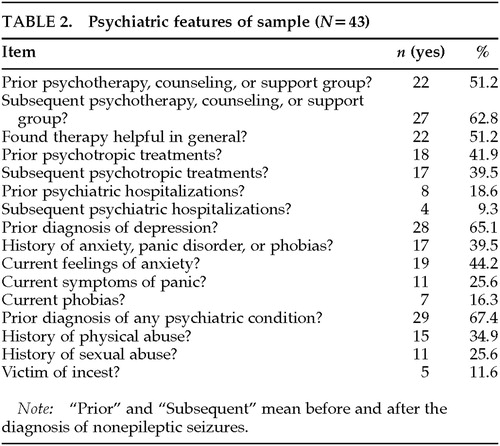

| • | 2. Psychiatric factors (Table 2>): This section dealt with symptoms of anxiety and depression, outpatient or inpatient psychiatric diagnoses and interventions, and how good the patient felt about him- or herself. We asked patients whether they had been sexually or physically abused anytime in life. We did not define sexual or physical abuse, but we made it clear that these should be treated as separate categories. Sexual abuse included incest experiences. | ||||

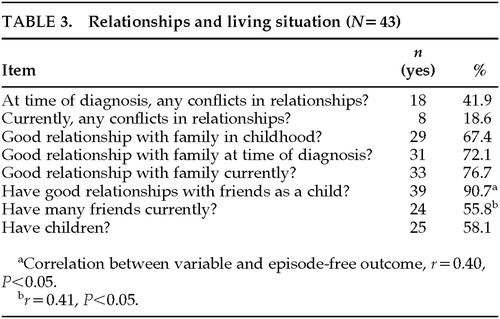

| • | 3. Socioeconomic variables (Table 3): This section concerned occupational status and sources of income. | ||||

| • | 4. Relationships: These questions examined marital status, living situation, other family relationships, conflicts, friendships, and patient assessment of the quality of these relationships. Questions were open-ended, and no specific definition was given to subjects for these terms. | ||||

| • | 5. Reactions to receiving the diagnosis of NES: This section examined patients' feelings about receiving the diagnosis of NES and whether they agreed or disagreed with the diagnosis. | ||||

| • | 6. Litigation: This section inquired about litigation at the time of NES diagnosis and currently.17 | ||||

To investigate outcome, we examined the frequency of episodes at the time of follow-up. Patients reported whether they were episode-free, had less frequent episodes, had episode frequency unchanged, or had an increase in episode frequency. We did not ask patients to specify the percentage of increase or decrease in episode frequency.

We inquired whether patients were still taking AEDs and if they had undergone subsequent hospitalizations for evaluation or treatment of NES or any new psychiatric hospitalizations.

Statistical Analysis

Two-by-two chi-square and, where appropriate, correlation coefficients were calculated to establish potential relationships with episode frequency at the time of follow-up. For this purpose we collapsed outcome categories into episode-free versus persistent (reduced, unchanged, or worse). Because of the exploratory nature of this investigation, we did not correct for the multiple statistical tests.

RESULTS

Fifty-five patients met study entry criteria; of these, 8 could not be reached and 4 declined to enter the study. Of the 43 patients (39 female, 4 male) who participated, 36 (83.7%) had NES alone, and 7 (16.3%) had a prior history of highly probable or confirmed epileptic seizures. The average age at onset of either NES or epileptic seizures was 33.6 years (minimum age 1 year, maximum age 50, SD=13.5).

Neither a history of epileptic seizures nor the age at onset of episodes predicted outcome.

Outcome

Eight patients (18.6%) were episode-free at the time of follow-up; 24 (55.8%) reported a reduction in frequency but persistence of episodes; 7 (16.3%) reported no change; and 4 (9.3%) reported an increased frequency. Fourteen patients (32.6%) were hospitalized because of recurrent episodes following the time of NES diagnosis.

AEDs were not prescribed in 8 cases. Among the remaining 35 cases, AEDs were stopped in 14 (40%) and continued in 20 (57.1%); data were missing in 1 case. Thus, 20 patients (46.5% of the entire sample) were receiving AEDs at follow-up.

Psychiatric and Emotional Variables

Responses to questions relating to psychiatric issues are highlighted in Table 2. Notable responses include high rates of prior or current depression and anxiety (e.g., 44.2% with current anxiety symptoms). There was no statistically significant correlation between outcome and receiving one of the psychiatric interventions listed in the table.

Patients also described how they felt about themselves at the time of follow-up compared with at the time of diagnosis. Overall, patients reported that their feelings about themselves improved. At the time of diagnosis, 16 patients (37.2%) indicated they felt “bad” about themselves, 11 (25.6%) felt “neutral,” and 16 (37.2%) felt “good.” At the time of follow-up, 4 (9.3%) indicated they felt “bad,” 5 (11.6%) endorsed feeling “neutral,” and 34 (79.1%) indicated they felt “good” about themselves.

Of the 35 patients who were not episode-free at the time of follow-up, 20 patients (57.1%) were hopeful that they would get better, 7 patients (20%) did not expect to improve, and 8 (22.9%) were unsure.

None of the psychiatric and emotional variables correlated with frequency of episodes at follow-up.

Relationships and Living Situation

Table 3 displays responses to questions regarding relationships and patients' living situations. At the time of monitoring, 4 patients (9.3%) reported that they lived alone; 19 (44.2%) lived with a spouse or significant other; 13 (30.2%) lived with a parent, friend, or relative; 6 (14.0%) lived with their adult children; and 1 (2.3%) lived in a group home. Twenty-four patients (55.8%) reported having many friends currently, 17 (39.5%) reported having few friends, and 2 (4.7%) indicated that they had no friends. At the time of diagnosis, 16 patients (37.2%) were single, 18 (41.9%) were married, 2 (4.7%) were separated, 5 (9.3%) were divorced, 1 (2.3%) was widowed, and 1 (2.3%) reported cohabiting with a lover. At the time of follow-up, there were no significant changes in the patients' living situations, except that 2 of the 18 patients who were married at the time of diagnosis were now divorced, and 1 was separated.

Patients who reported having many friends currently (r=0.41, P<0.05) or having good relationships with friends as a child (r=0.40, P<0.05) were more likely to be episode-free.

Income and Employment

At the time of follow-up, 14 patients (32.6%) were working, 29 (67.4%) were unemployed, and information was unspecified in 1 case. However, the main source of income was Social Security Disability Income in 18 (41.9%), family assistance in 5 (11.6%), employment in 8 (18.6%), employment of the spouse in 8 (18.6%), and “other” in 5 (11.6%).

None of these variables were predictive of outcome.

Attitude Toward Diagnosis

Patients described their strongest feeling after receiving the diagnosis of NES. One patient (2.3%) felt happy, 5 (11.6%) were relieved, 8 (18.6%) felt neutral, 7 (16.3%) experienced anxiety, 11 (25.6%) felt sad, 8 (18.6%) were angry, and 3 (7.0%) could not describe their feelings.

Nineteen patients (44.2%) agreed with the diagnosis of NES at the time of diagnosis, 7 (16.3%) disagreed, and 17 (39.5%) were unsure. There was no change in sentiment at the time of follow-up, except that 2 patients who were unsure at the time of diagnosis now agreed and 1 now disagreed with the diagnosis.

None of these factors predicted NES outcome.

Litigation

Five patients (11.6%) had litigation pending at the time of monitoring, with 4 (9.3%) still pending at the time of follow-up. The specific nature of the litigation was not investigated in this study.

Subjects with pending litigation were less likely to be episode-free (r=–0.36, P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

Our study of rigorously diagnosed NES patients found that resolution of NES is infrequent after the diagnosis is made. Only 8 patients stopped having episodes, and one-third of our patients were rehospitalized because of their episodes.

We also determined two factors that to our knowledge have not been previously identified as associated with good NES outcome. Patients who reported good relationships with childhood friends or who reported having many current friendships had a better prognosis for episode-free outcome. A history of establishing friendships may suggest higher functioning and better interpersonal skills, which could lead to better social and emotional adjustment after the diagnosis of NES is made. Such patients may have more opportunity and more personal inclination to express stress and psychological conflicts verbally rather than with NES clinical activity. We believe that promoting support systems for NES patients may improve prognosis. The importance of these factors should be clarified in future studies using psychiatric interviews.

Our study also revealed that pending litigation predicts poor outcome. Although the specific nature of the litigation was not examined, secondary gain related to compensation cases may have led patients to continue to experience episodes. Additionally, litigation is likely to be associated with additional stress, which may exacerbate NES. Future studies are needed to examine the specific circumstances and psychiatric diagnoses of such patients to clarify the context of the litigation and possible malingering.

Our series had the lowest percentage of episode-free outcomes (only 19%), compared with 29% to 40% resolution of episodes in other series (Table 1).9–11,15,18 Some of this variability may relate to differences in duration of follow-up, inclusion of pediatric age groups, or potential differences in socioeconomic and psychiatric characteristics and in the nature of interventions offered. Our study did not ask patients to specify actual numbers of episodes experienced before and after the NES diagnosis; patients may have overestimated improvement in NES when asked to summarize outcome into simple categories of increase or decrease in frequency.

More than half of the patients who had been on AEDs prior to the video-EEG evaluation remained on AEDs at the time of follow-up. Our overall rate of patients on AEDs after NES diagnosis (47%) is higher than the 35% to 44% rate of similar patients reported in other series.9,10,15 In part, this discrepancy reflects the relatively short duration of follow-up as well as the strategy used at our center of focusing on psychological interventions before making any changes in AED regimen.

We speculate that anxiety symptoms were strongly endorsed by our patients because of the ubiquitous role of anxiety in a number of psychiatric syndromes common to NES patients. For example, some psychodynamic theories suggest that conversion disorder arises from an attempt to reduce anxiety by keeping an internal psychological conflict or need out of conscious awareness.19 However, this anxiety cannot be successfully repressed, as documented on psychological testing of patients with active conversion symptoms.20,21 Sheehan and Sheehan have even argued that anxiety is at the core of all somatoform disturbances.22 In dissociative disorder (another condition considered to be common among NES patients), anxiety and panic symptoms may relate to the repeated and long-term exposure to emotionally traumatic events earlier in life, which causes a feeling of intense fear, helplessness, and loss of control.23 Dissociative experiences have been suggested by some to represent a fear-conditioned response.24,25

Snyder et al.26 diagnosed panic disorder in 14 of 20 NES patients examined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). They argued that panic disorder is highly prevalent but poorly recognized among NES patients, noting that highly somatizing patients may not volunteer their panic symptoms unless directly asked. In a report of NES patients with psychiatric diagnoses other than conversion disorder, panic and other anxiety disorders were the most common causes for NES.27 Anxiety disorders were present alone or in combination with other Axis I diagnoses in approximately 50% of cases in another series of NES patients.28

We found no correlation between NES outcome and the presence or absence of an anxiety disorder. It is still possible, however, that NES outcome correlates with intensity of anxiety rather than the presence of a disorder; this variable was not examined in our study.

A history of physical abuse was reported in 35% of our patients, and sexual abuse was noted in 26%. This level is fairly comparable to a range of 32% to 67%27,28 for physical or sexual abuse reported in other NES series. Accurate rates of physical and sexual abuse in our study and other series may be difficult to ascertain. Specific definitions for these terms have not been well established. In our study, we did not give patients specific criteria to follow when answering this question, leading to more potential variability in patients' interpretation of this question. Further, patients may have been reluctant to share this information. Their denial may have led some patients in our study and other investigations to normalize their parents' behaviors and to deny that certain types of punishment were physical abuse.

In our series and in two other studies,9,15 involvement in psychotherapy, support groups, or counseling did not correlate with prognosis after the NES diagnosis was made. This is in contrast to the series of Meierkord et al.,11 which demonstrated favorable effects of these interventions on NES outcome. In the latter series, conversion disorder was noted in 21%, dissociative disorder was not mentioned, and depression or suicidality was noted as a separate category in up to 36% of cases. This pattern suggests that the nature of psychopathology encountered in those patients may have been more amenable to psychiatric intervention than was the case in other studies such as our own. Although our study found a majority of patients with a prior diagnosis of depression, we did not examine current depressive symptomatology. In no series were psychiatric interventions formally studied with randomization of therapies.

In our study, we do not have any information as to whether psychotherapy specifically addressed the problem of NES among individual patients. Our series did not investigate responses to specific types of psychiatric interventions, but rather grouped different modalities of treatment together. Patients with more severe psychopathology, and therefore a lower likelihood for NES resolution, may also have been more likely to receive psychiatric follow-up, resulting in a poor correlation between psychiatric interventions and a good outcome. Our study did not examine psychiatric diagnoses at the time of NES diagnosis, and therefore it remains unclear whether poor outcome is related to the nature of the psychiatric condition or the failure of those disorders to respond to therapy. There is therefore a compelling need for rigorously designed controlled trials of psychiatric interventions for NES.

Another novel area of investigation was an assessment of patient reactions to receiving the NES diagnosis. We found these reactions to be diverse. Patients who stated that they were “happy” or “relieved” to receive the diagnosis did not necessarily have a better prognosis. Although it would be intuitive to expect such patients to resolve their episodes, an appreciation of the complexity of psychopathology associated with NES would suggest otherwise.

The present study will need to be repeated in a larger series of NES patients, particularly because of the large number of variables studied and the possibility that some of the statistically significant results were chance findings rather than definitive associations. Further clarification of prognostic factors will be highly valuable in the evaluation and treatment of patients with this disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Elizabeth Bowman, M.D., and Max Fink, M.D., for their review of this manuscript.

|

|

|

1 Ozkara C, Dreiffus FE: Differential diagnosis in pseudoepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1993; 34:294–298Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Bazil CW, Kothari M, Luciano D, et al: Provocation of nonepileptic seizures by suggestion in a general seizure population. Epilepsia 1994; 34:768–770Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Gulick TA, Spinks IP, King DW: Pseudoseizures: ictal phenomena. Neurology 1982; 32:24–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Dodrill CB, Wilkus RJ, Batzel LW: The MMPI as a diagnostic tool in non-epileptic seizures, in Non-Epileptic Seizures, edited by Rowan AR, Gates JR. New York, Demos, 1993, pp 211–219Google Scholar

5 Cohen R, Suter C: Hysterical seizures: suggestion as a provocative EEG test. Ann Neurol 1982; 11:391–395Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Kanner AM, Morris HH, Luders H, et al: Supplementary motor seizures mimicking pseudoseizures: some clinical differences. Neurology 1990; 40:1404–1407Google Scholar

7 Gates JR, Ramani V, Whalen S, et al: Ictal characteristics of pseudoseizures. Arch Neurol 1985; 42:1183–1187Google Scholar

8 Gumnit RJ: The differential diagnosis of epilepsy: nonepileptic paroxysmal disorders, in The Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice, edited by Wyllie E. Philadelphia, Lea and Febiger, 1993, pp 692–696Google Scholar

9 Walczak TS, Papacostas S, Williams DT: Outcome after diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1995; 36:1131–1137Google Scholar

10 Krumholz A, Niedermeyer E: Psychogenic seizures: a clinical study with follow-up data. Neurology 1983; 33:498–502Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Meierkord H, Will B, Fish D, et al: The clinical features and prognosis of pseudoseizures diagnosed using video-EEG telemetry. Neurology 1991; 41:1643–1646Google Scholar

12 Wyllie E, Friedman D, Luders H, et al: Outcome of psychogenic seizures in children and adolescents compared with adults. Neurology 1991; 41:742–744Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Ramani V, Gumnit RJ: Management of hysterical seizures in epileptic patients. Arch Neurol 1982; 39:78–81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Betts T, Boden S: Diagnosis, management and prognosis of a group of 128 patients with non-epileptic attack disorder, part I. Seizure 1992; 1:19–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Lempert T, Schmidt D: Natural history and outcome of psychogenic seizures: a clinical study in 50 patients. J Neurol 1990; 237:35–38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Shen W, Bowman E, Markand O: Presenting the diagnosis of pseudoseizure. Neurology 1990; 40:756–759Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Rowan A, Gates J: Non-epileptic Seizures. Boston, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993Google Scholar

18 Kristensen O, Alving J: Pseudoseizures: risk factors and prognosis. Acta Neurol Scand 1992; 85:177–180Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Martin RL, Yutzy SH: Somatoform disorders, in Psychiatry, edited by Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1997, pp 1119–1155Google Scholar

20 Lader M, Sartorious N: Anxiety in patients with hysterical conversion symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1968; 31:490–495Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Mears R, Horvath TB: “Acute” and “chronic” hysteria. Br J Psychiatry 1972; 121:653–657Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH: The classification of anxiety and hysterical states, II: toward a more heuristic classification. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1982; 2:386–393Medline, Google Scholar

23 Andreasen NC: Posttraumatic stress disorder, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1985, pp 918–924Google Scholar

24 Teicher MH, Glod CA, Surrey J, et al: Early childhood abuse and limbic system ratings in adult psychiatric outpatients. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 5:301–306Link, Google Scholar

25 Ito Y, Teicher MH, Glod CA, et al: Increased prevalence of electrophysiological abnormalities in children with psychological, physical, and sexual abuse. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 5:401–408Link, Google Scholar

26 Snyder SL, Rosenbaum DH, Rowan AJ, et al: SCID diagnosis of panic disorder in psychogenic seizure patients. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:261–266Link, Google Scholar

27 Alper K, Devinsky O, Perrine K, et al: Psychiatric classification of nonconversion nonepileptic seizures. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:199–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Bowman ES, Markand ON: Psychodynamics and psychiatric diagnoses of pseudoseizure subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:57–63Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar