Age Disorientation in Schizophrenia

Abstract

The authors investigated age disorientation in chronic schizophrenia to determine whether specific symptomatic, neurologic, and cognitive disturbances were linked to its presentation. Disorientation to their age was detected in 30% (16/54) of the schizophrenic patients in a chronic care facility. In matched comparisons, age-disoriented patients showed lower educational achievement, poorer mental state performance, and a greater severity of symptoms, as well as more severe motor and sensory impairments. Levels of social withdrawal did not differentiate the two groups. A two-hit model consistent with neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative processes is proposed to explain the data.

Age disorientation is defined as misstating one's age by 5 or more years. It is observed in a substantial number of chronically ill, institutionalized schizophrenic patients. Prevalence estimates have been limited to data from surveys of hospitalized mental patients in chronic care facilities, where approximately 25% of patients are age disoriented.1–5 The majority of age-disoriented schizophrenic patients understate their age. In fact, about 10% of schizophrenic subjects report an incorrect subjective age that is within 5 years of their age at illness onset.2 Age-disoriented patients are generally older, have a longer current admission, and were younger at first admission than age-oriented patients.2,3 All of these findings are consistent with a subtype of schizophrenic illness characterized by early onset and poor prognosis.

Age-disoriented patients are cognitively more impaired than their age-oriented counterparts. In fact, age disorientation serves as a marker for global cognitive impairment. Age-disoriented schizophrenia patients are generally unable to answer temporally oriented questions.2,6 They perform poorly on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)7 or similar tests.3,6,8 Age-disoriented patients show widespread cognitive impairment on tests of vocabulary, associational learning, orientation, general knowledge, and other functions in comparison to age-oriented subjects.6

Whether cognitive impairment is present to a greater degree premorbidly among these patients is not yet established, but some data support this.6 Others have reported that rated school performance9 and grade level obtained3 do not distinguish age-disoriented from age-oriented subjects. Some have suggested that marked cognitive decline occurs following first break.6,9 Harvey et al.3 reported that age-related decline in MMSE scores is dramatically greater among age-disoriented schizophrenia patients than age-oriented subjects, consistent with more rapid deterioration. The relationship between premorbid functioning and the progression of impairment in schizophrenia remains to be established.9

The cognitive features of age-disoriented patients are well described, but clinical features defining this group remain obscure. Three reports have specifically addressed the issue of symptomatology. One study found age disorientation to be unrelated to symptoms.10 Another documented more negative symptoms among age-disoriented patients, despite positive symptom profiles similar to those of age-oriented subjects.3 Crow and Mitchell's earlier report1 suggested that those age-disoriented patients most “stuck”—that is, whose subjective ages were closest to their ages at onset—had the most severe symptoms, particularly manneristic speech.

Harvey et al.3 believe the pattern of increased negative symptoms and cognitive impairment among the age disoriented, which are generally less variable features than psychotic symptoms, may reflect a more stable brain disorder rather than neurotransmitter dysfunction. Consistent with this hypothesis, Goldberg et al.8 found increased ventricle/brain ratios among age-disoriented schizophrenia patients with dementia, compared with demented age-oriented patients. Insofar as ventricular measures are an indicator of gross neuropathology, age-disoriented schizophrenia patients may have more extensive brain pathology than age-oriented schizophrenia patients.

Although age-disoriented patients appear to be younger at first admission2,3 and to have a more chronic course,2 age disorientation is not simply a function of either chronicity or prolonged hospitalization.10,11 Crow and others1,2,5 have suggested that age disorientation is a failure of an important learning mechanism, a cognitive defect commonly associated with organic brain disease. These patients can no longer update their temporal “files,” and thus “time stands still” for them. Crow's group has attempted to link this phenomenon to temporal lobe abnormalities.

Despite a growing literature, understanding of age disorientation is limited. Cognitive disturbances have increasingly become a focus of treatment and rehabilitation efforts in schizophrenia. Given the possibility that age disorientation may result from neurodevelopmental problems, neurodegeneration, or both, characterizing its relationship to other aspects of schizophrenic illness, including natural history, may yield additional insights. Selten and Cath,12 attempting to explain the low prevalence of age disorientation in a Dutch sample, suggested a third explanation: age disorientation may be the result of an interaction between a severe form of the illness and “poor psychosocial treatment.” Institutional isolation with low or poor environmental stimulants and cues may increase the potential for disorientation. Further, if social cues are a factor in age disorientation, one would anticipate that the closer one is to one's birthday—and reminders of it—the greater the orientation.

We surveyed a group of chronically ill patients to identify age disorientation and other psychiatric and neurological features. The goal was to replicate certain prior observations regarding age disorientation and to extend knowledge of the correlates (e.g., risk factors, symptoms, cognitive disturbances) of this feature of psychopathology. We were particularly interested in voluntary and involuntary movements. Crow and Stevens2 and others have suggested that nonlocalizing motor signs might be part of a constellation of features that co-occur in an early-onset, poor-prognosis subtype. We therefore further investigated the relationship of age disorientation to age orientation in chronic schizophrenic patients across a range of demographic, clinical, motor, sensory, and cognitive measures.

METHODS

Subjects

We collected data from 54 subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia according to DSM-III-R criteria.13 All of the subjects were chronically ill inpatients in three wards of a state hospital, receiving conventional neuroleptic treatments. (The total hospital population was 85; patients not included in this sample had diagnoses of organic mental disorder, other psychotic disorders, or developmental disorder.) An independent diagnosis of schizophrenia was generated, based on the clinical record and an interview of the patient by one of two psychiatrists. Informed consent was obtained, and data collection was accomplished in the following 2- to 3-day period.

Demographic and Premorbid Information

Age, years of education, age at first psychiatric hospitalization, length of illness, and current medication (converted to chlorpromazine equivalents) were collected through a clinical interview and a record review, and, when possible, confirmed with key informants, including family members and other caregivers. To determine age orientation, the subject was simply asked his or her age during the course of the clinical interview. Consistent with other reports,2 we defined age disorientation as misstating one's age by more than 5 years (in either direction). We considered school grade level obtained to be a measure of premorbid achievement. Length of illness was determined by subtracting the subject's age at first hospitalization from the current age.

The sample of 54 subjects included 21 females and 33 males, with a mean age of 44.7 years (SD=13.7), mean years of education of 10.1 years (SD=2.65), mean length of illness of 23.5 years (SD=13.5), and mean age of first hospitalization of 21.2 years (SD=8.3).

Measures

Positive and negative symptoms, as well as general pathology, were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).14 This scale also includes a measure of both passive and active social withdrawal. Additionally, the subjects' overall level of functioning was rated on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF).15

Rigidity, tremor, stiffness, and similar features were rated with the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale.16 The Abnormal Involuntary Movements Scale (AIMS)17 was administered, and global judgments about the severity and associated incapacitation of such abnormalities were also assessed.

A variety of neuromotor tasks focused on voluntary motor movements as well as involuntary motor and nonlocalizing sensory signs. Subjects were asked to produce simple movements of the hands, head, and eyes, as well as more complex sequences such as fist-edge-palm, fist-ring, and Ozeretski actions; scoring of performance was based on a modification of scales developed by Buchanan and Heinrichs.18 Ratings were also made of stereognosis and graphesthesia, coordination, station, and gait.19,20

Two measures of global cognition were administered. The MMSE7 was given to test subjects' orientation (2 items), registration (1 item), attention and calculation (1 item), recall (1 item), language abilities (6 items), and copying (praxis; 1 item). Further, a subset of the Executive Interview21 was administered; this test measures the subject's ability in five different areas, including a number-letter task, word fluency, anomalous sentence repetition, memory/distraction task, and serial order reversal.

As a measure of motor lateralization, subjects drew two lines with both their right and left hands. These drawn lines were scanned into a computer and digitized, and a regression line was fitted to the resulting points. Using the root mean square error from each regression line (i.e., each line's deviation from linearity), a motoric lateralization index (absolute laterality) was constructed. This index can range from 0.0 (poorly lateralized) to 1.0 (strongly lateralized).22

To obtain a speech sample, subjects were asked to describe a Brueghel painting, “The Wedding Feast,” and were prompted (e.g., “Anything else?”) when their spontaneous comments ended. Samples at least 100 words long were tape recorded and transcribed. The type/token ratio, a measure of language repetitiveness, was obtained by dividing the total number of words (tokens) spoken into the number of different words (type) and correcting for total sample length.23

As a measure of context memory, subjects listened to an audiotape of four word lists of 20 words each, read slowly in a monotone with a 2-second pause between words. Subjects were instructed to listen to each list and then write what they heard, with no time limits set on recall. The four lists varied in contextual constraint (i.e., from a zero-context word list by graded degrees of context to a halfway approximation of a normal English sentence). These lists are identified as MS1, MS2, MS3, and MS4, respectively, in increasing order of degree of context. MS1, the zero-order list, has no context connections between words, and recall of this list thus reflects rote learning. Recall gain due to increased context was estimated by the sum of items recalled from the three constrained lists (MS2, MS3, MS4).24,25

A lexical decision task was administered; this is an assessment of semantic association, measured by speed of word recognition. The subjects were shown pairs of words on a computer screen. The first string of letters, called a “prime,” is followed shortly by the second, the “target.” The subjects indicate whether or not the target word is a real English word by making a yes or no response on the keyboard. Both accuracy and response latencies are determined. Typically, target words that are semantically related to or semantically activated by the prime words elicit shorter response latencies than unrelated pairs. This provides an index of strategic and automatic responses.26

Analysis

Each age-disoriented subject was matched for age and length of illness with an age-oriented subject. Matched-pair t-tests were conducted to compare the two groups. Two-tailed significance testing was employed, and minimum significance P-values were set at P<0.05, although trends are reported with P-values >0.05 and <0.10. We chose a conservative approach because we knew on the basis of previous studies that age-disoriented patients would likely do worse on any measure. Using one-tailed tests would have elevated our trend observations to significance. When appropriate, chi-square examinations were also used to compare the groups. Finally, relationships among variables in both the age-oriented and age-disoriented groups were examined with Spearman rank-order correlations. Means and standard deviations are reported.

RESULTS

Age Disorientation

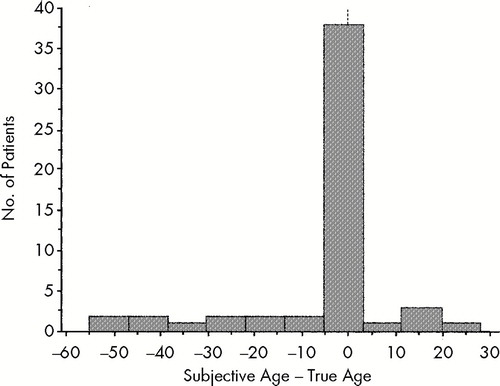

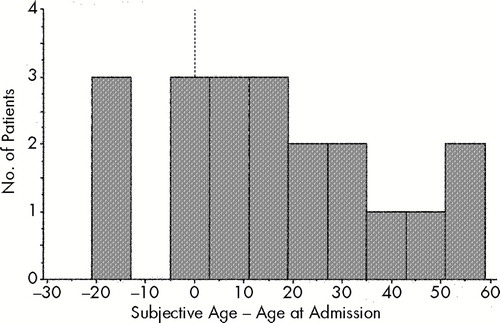

Consistent with earlier reports, 16 of our 54 subjects (29.6%) reported a subjective age that was more than 5 years different from their chronological age (Figure 1). However, only 3.7% (2/54) of our sample thought their current age was within 5 years of their age at the time of their first hospitalization (Figure 2).

Demographics

The 16 matched age-disoriented and age-oriented pairs did not differ in age, age at first hospitalization, length of illness, gender distribution, or current medication (chlorpromazine equivalents). The age-disoriented group was significantly less well educated than the age-oriented group (years of education: 8.5±2.6 vs. 11.1±2.9; t= 2.8, df=15, P=0.01).

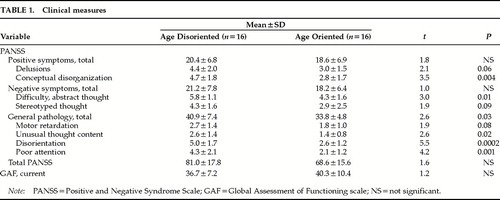

Clinical Measures

Although there were no differences between the two groups in total positive or total negative symptoms or in current global level of functioning, there was a significant difference in terms of total overt pathology (Table 1). Examination of the specific PANSS items revealed that the age-disoriented group was consistently more delusional and more conceptually disorganized and showed increased stereotyped thinking, motor retardation, unusual thought content, disorientation, and poor attention. They also had more difficulty with abstract thinking.

Involuntary and Voluntary Movements and Nonlocalizing Sensory Signs

The age-disoriented group had more severe involuntary movements of the orofacial area than the age-oriented group (Table 2). According to Schooler and Kane's research criteria for assessing tardive dyskinesia (TD),27 the same percentage of each group (6/16; 37.5%) showed signs of probable TD. More severe voluntary movement disorders were clearly evident among the age disoriented, including sequential motor performance, coordination, and general clumsiness. The age-disoriented group had significantly more severe graphesthesia but not stereognosis.

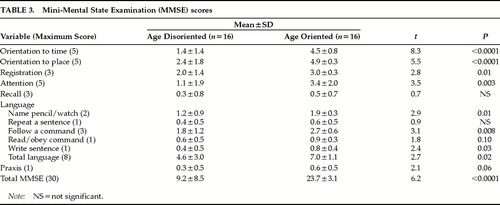

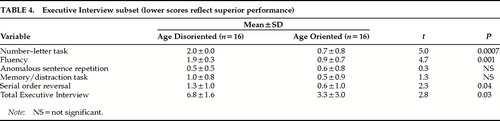

Cognitive Measures

The age-disoriented patients did worse on the total MMSE and on each individual domain of the MMSE except recall, where both patient groups were close to floor (Table 3). A breakdown of the components of the language measure on the MMSE revealed that age-disoriented patients had poorer language abilities across all domains with the exception of sentence repetition. Further, age-disoriented patients lagged in the number/letter task, word fluency, and serial order reversal from the Executive Interview, as well as scoring poorly on the total Executive Interview (Table 4).

There were no observed laterality differences between the two groups (laterality: age disoriented, 0.19±0.15; age oriented, 0.23±0.16; t=0.4, not significant).

The remainder of the cognitive battery was difficult to evaluate because completion rates for both groups fell dramatically for lexical decision, oral language sample, and context memory tasks, thereby reducing the available N (Table 5). It is notable, however, that age-disoriented patients were consistently worse at completing these tasks than were age-oriented patients. There were no significant differences between the age disoriented and the age oriented in terms of rote memory on the Miller-Selfridge recall task (words recalled: age disoriented, 1.5±1.3; age oriented, 3.1±2.5; t=1.4, df=6, not significant). But there were significant differences in context memory (words recalled: age disoriented, 4.8±3.4; age oriented, 12.5±7.4; t=2.6, df=4, P=0.05). Furthermore, results of the speech sample analyses suggest that age-disoriented patients are more repetitive than age-oriented patients (type/token ratio: age disoriented, 3.3±0.7; age oriented, 4.4±0.9; t=3.0, df=6, P=0.02).

Social Withdrawal

There were no mean differences between the age-disoriented and age-oriented groups on the two PANSS measures of withdrawal: passive/apathetic social withdrawal (age disoriented, 2.8±2.0; age oriented, 2.7±1.4; t=0.1, df=15, not significant) and active social avoidance (age disoriented, 2.3±1.7; age oriented, 2.1±1.2; t=0.4, df=15, not significant). These variables were then recoded categorically, with a score of 1 (absent) or 2 (minimal) reflecting the absence of the item rated and a score of 3 (mild) or higher reflecting the presence of the item rated. There were no distribution differences between the two groups on either passive/apathetic social withdrawal (% withdrawn: age disoriented, 44%; age oriented, 63%; χ2=0.78, not significant) or active social avoidance (% avoiding: age disoriented, 29%; age oriented, 50%; χ2=1.4, not significant).

Point of Assessment in Relation to Birthdate

The two groups did not differ in the mean length of time from their assessments to their birthdays (months between assessment and birth month: age disoriented, 3.1±4.0; age oriented, 4.4±3.8; t=1.00, df=15, not significant). Further, within the age-disoriented group there was no relationship between the proximity of assessment month to birth month and the severity of age disorientation (Spearman rho=0.168, not significant).

Relationships Between Variables

Within the age-disoriented group, there was no relationship between total MMSE score and either rote memory on the Miller-Selfridge recall task (Spearman rho=–0.25, n=6, not significant), context memory on the same recall task (Spearman rho=0.4, n=6, not significant) or the type/token ratio generated from the speech sample (Spearman rho=0.15, n=9, not significant).

DISCUSSION

Approximately 30% of this sample of long-stay schizophrenic patients was age disoriented. The distribution of reported ages among the age disoriented did not support a connection to age at the time of onset of their schizophrenia. Age-disoriented patients have certain, more severe, psychiatric symptoms, more voluntary motor disturbances, more orofacial involuntary movements, and more severe nonlocalizing sensory signs. Most of the assessed cognitive abilities of the age disoriented (i.e., MMSE performance, context memory, speech repetitiveness) are more disrupted than those of matched age-oriented schizophrenic control subjects. However, within the age-disoriented group there was no relationship between MMSE total scores and other cognitive features, suggesting that age disorientation is not merely an issue of increased severity. Finally, age disorientation is correlated with lower educational achievement (impaired cognitive functioning) prior to first hospitalization.

We propose that age disorientation may represent a unique mixture of cognitive and motor deficits that constitutes a subtype of schizophrenia. The occurrence of nonlocalizing motor signs and the greater orofacial movements give credence to the idea of a subtype that involves more severe neuropathology. Further, the present data also provide evidence consistent with a progressive deterioration among a subsample of severely afflicted schizophrenic subjects. Our clinical impression is that age disorientation is found primarily in inpatient settings. This is consistent with other findings that patients with the worst cognitive impairments have a more severe form of schizophrenia, thereby requiring chronic institutionalization. Our age-disoriented patients did worse on the MMSE than schizophrenic samples typically do, but comparably to other age-disoriented schizophrenic samples. They are more similar in this regard to dementia patients than to other schizophrenia patients. This is consistent with Harvey and co-workers'3 findings of greater cognitive deterioration among age-disoriented schizophrenic patients. Analysis of the pattern of deficits shown by the age-disoriented patients—for example, the anomic performance on the MMSE—buttresses the comparison with other dementing conditions.

However, the hypothesis of a neurodevelopmental lesion is also consistent with many of these findings. There is no difference in motor lateralization between the age-disorientated and age-oriented patients. One would anticipate decreased lateralization in patients whose deterioration begins at an earlier age (Manschreck et al., unpublished). Furthermore, one would predict that this group would have been hospitalized at an earlier age, which they were not. One explanation to reconcile this apparent inconsistency is to invoke a two-hit model combining neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative processes, such that the onset of symptomatology occurs at similar times but decline occurs at an accelerated rate among those who become age disoriented. Moreover, this proposal would also be consistent with increased occurrence of orofacial movements in the age-disoriented group.

One suggestion to explain the progressive decline is that it may be the consequence of medication failure or noncompliance. Untreated schizophrenia, in general, has a worse prognosis than is the case when there is aggressive, early intervention.28 Olney and Farber29 have proposed a novel hypothesis based on the observation that drugs that target N-methyl-d-asparate (NMDA) glutamate receptors mimic schizophrenia. Excess dopamine inhibits glutamate release, thereby rendering NMDA receptors hypoactive. It is therefore not surprising that antipsychotic agents, both typical and atypical, activate NMDA receptors.30 The NMDA hypofunction hypothesis explains many manifestations of schizophrenia not adequately explained by the dopamine hypothesis.30 NMDA hypofunction ultimately produces cytotoxicity, volumetric change, and cognitive deterioration, as well as increased motor pathology. It is also consistent with the well-known observation that schizophrenia patients early on manifest more positive symptoms but eventually deteriorate to the “burned-out” mixture characterized by negative symptoms and abulia.

There were no apparent differences between the age-oriented and age-disoriented schizophrenia patients in terms of social withdrawal. Selten and Cath's12 proposal about age disorientation was that social withdrawal, perhaps in conjunction with other negative symptoms and the institutional setting, may lead one to be less aware of the environment, including the calendar, and hence less likely to be oriented to the date. All of our patients, whether age oriented or not, were in the same institutionalized setting. There was no apparent difference in the social isolation of these patients, and little difference in negative symptomatology. Moreover, a psychosocial pathway would not produce the motor dysfunction clearly demarcating the age-disoriented groups. Finally, there was no relationship between proximity of subjects' birthdays to time of assessment and either the presence or severity of age disorientation. Since our facility marked birthdays with a celebration, increased attention would help orient a patient to age. The data do not support a psychosocial explanation.

As Crow and Stevens2 suggested, age-disoriented schizophrenic individuals have more motor abnormalities than their age-oriented counterparts. Our study has carried this work further by identifying specific movement abnormalities among age-disoriented schizophrenia patients that may identify the age-disordered group as a whole. These findings provide convincing evidence that age disorientation predicts poor outcome in schizophrenia. More severe motor abnormalities have previously been found to predict poor outcome.31,32 Specifically, the emergence of involuntary orofacial movements has been associated with more severe cognitive decline among schizophrenic samples,33 irrespective of age disorientation.

Little is known about the incidence of age disorientation. Because motor abnormalities among schizophrenic individuals may be detected premorbidly,34 following high-risk samples with identified motor abnormalities may allow improved understanding of the pattern of cognitive deterioration culminating in age disorientation. How do age-disoriented schizophrenic patients compare with age-disoriented subjects bearing other psychiatric-disorder diagnoses, as studied by Lombardi et al.?35 When does age disorientation arise and what is its natural history? These are questions worthy of further pursuit.

The subject group in this study consisted of schizophrenic patients chronically institutionalized in an era of deinstitutionalized community treatment; thus, they are very impaired. Because of this severity, conducting intrasample comparisons of matched age-disoriented and age-oriented subjects may diminish the likelihood of finding distinguishing features of age-disoriented patients from the general population of schizophrenia patients. Chronicity results from treatment resistance. Both groups share this property, which leads to sampling bias.

Further limitations of the study include the failure of some subjects to complete the entire battery of assessments, difficulty in determining precise age at onset, and the possible unreliability of subjective age reports (i.e., whether the patients are consistently age disoriented). These assessment concerns are common features in studies of age disorientation. In this study, age at onset was assessed among the entire sample on the basis of a record review of first admission to a psychiatric hospital for treatment of schizophrenia. Prior reports have indicated that age-disoriented patients' subjective age responses are reliable measures—that is, those who are age disoriented at one assessment point tend to be disoriented at follow-up.3,6

In summary, we report the prevalence of age disorientation in schizophrenic patients among a chronically hospitalized population. The distinguishing features of this subgroup include increased severity of certain symptoms; premorbid cognitive disorder; and a range of current cognitive, sensory, and motor disturbances. A two-hit neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative model best fits our data. Moreover, because these patients may be identifiable early on in their illness, our hypothesis of a possible subtype is testable. Further investigation of this potential subtype offers a new approach to improving the taxonomy of schizophrenia.

FIGURE 1. Distribution of subjective age (in years) in relation to true age in the whole population of 54 patients

FIGURE 2. Distribution of subjective age in relation to age at admission of the group of 16 age-disoriented subjects

|

|

|

|

|

1 Crow TJ, Mitchell WS: Subjective age in schizophrenia: evidence for a subgroup of patients with defective learning capacity? Br J Psychiatry 1975; 126:360–363Google Scholar

2 Crow TJ, Stevens M: Age disorientation in chronic schizophrenia: the nature of the cognitive deficit. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:137–142Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Harvey PD, Lombardi J, Kincaid MM, et al: Cognitive functioning in chronically hospitalized schizophrenic patients: age-related changes and age disorientation as predictor of impairment. Schizophr Res 1995; 17:15–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Smith JM, Oswald WT: Subjective age in chronic schizophrenia (letter). Br J Psychiatry 1976; 128:100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Stevens M, Crow TJ, Bowman MJ, et al: Age disorientation in schizophrenia: a constant prevalence of 25 per cent in a chronic mental hospital population? Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:130–136Google Scholar

6 Liddle PF, Crow TJ: Age disorientation in chronic schizophrenia is associated with global intellectual impairment. Br J Psychiatry 1984; 144:193–199Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Goldberg TE, Kleinman JE, Daniel DG, et al: Dementia praecox revisited: age disorientation, mental status, and ventricular enlargement. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 15:187–190Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Burich N, Crow TJ, Johnstone EC, et al: Age disorientation in chronic schizophrenia is not associated with pre-morbid intellectual impairment or past physical treatment. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:466–469Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Tapp A, Tandon R, Scholten R, et al: Age disorientation in Kraepelinian schizophrenia: frequency and clinical correlates. Psychopathology 1993; 26:225–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Gabriel A: Disorientation in chronic psychiatric patients. Canadian J Psychiatry 1997; 42:864–868Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Selten JPCJ, Cath DC: Low prevalence of age disorientation in Dutch long-stay patients. Schizophr Res 1995; 14:141–143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

14 Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale Manual. New York, Multi-Health Systems, 1986Google Scholar

15 First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis V: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1995Google Scholar

16 Simpson G, Angus JSW: A rating scale of extrapyramidal side-effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1970; 212(suppl):9–11Google Scholar

17 Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (publication ADM 76-338). Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976Google Scholar

18 Buchanan RW, Heinrichs DW: The Neurological Evaluation Scale (NES): a structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1989; 27:335–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Manschreck TC, Maher BA, Rucklos ME, et al: Disturbed voluntary motor activity in schizophrenic disorder. Psychol Med 1982; 12:73–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Manschreck TC, Ames D: Neurological features and psychopathology in schizophrenic behavioral disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1984; 19:703–719Medline, Google Scholar

21 Royall DR, Mahurin RK, True JE, et al: Executive impairment among the functionally dependent: comparisons between schizophrenic and elderly subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1813–1819Google Scholar

22 Blyler CR, Maher BA, Manschreck TC, et al: Line drawing as a possible measure of lateralized motor performance in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1997; 26:15–23Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Manschreck TC, Maher BA, Hoover TM, et al: Repetition in schizophrenic speech. Language and Speech 1985; 28:255–268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Miller G, Selfridge F: Verbal context and the recall of meaningful material. Am J Psychology 1950; 63:176–185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Manschreck TC, Maher BA, Redmond DA, et al: Laterality, memory and thought disorder in schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1996; 9:1–7Google Scholar

26 Manschreck TC, Maher BA, Milavetz JJ, et al: Semantic priming in thought-disordered schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res 1988; 1:61–66Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Schooler NR, Kane JM: Research diagnoses for tardive dyskinesia (letter). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:486–487Medline, Google Scholar

28 Wyatt RJ: Neuroleptics and the natural course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1991; 17:325–351Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Olney JW, Farber NB: Glutamate receptor dysfunction and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:998–1007Google Scholar

30 Coyle JT: The glutamatergic dysfunction hypothesis for schizophrenia. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1996; 3:241–253Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Johnstone EC, Macmillan JF, Frith CD, et al: Further investigation of the predictors of outcome following first schizophrenic episodes. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:182–189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Turner TH: A diagnostic analysis of the casebook of Ticehurst House Asylum, 1845–1890. Psychol Med 1992; 21(suppl):1–70Google Scholar

33 Waddington JL, Youssef HA: Cognitive dysfunction in chronic schizophrenia followed prospectively over 10 years and its longitudinal relationship to the emergence of tardive dyskinesia. Psychol Med 1996; 26:681–688Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Walker EF, Savoie T, Davis D: Neuromotor precursors of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995; 20:441–451Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Lombardi J, Harvey PD, White L, et al: Age disorientation in chronically hospitalized patients with mood disorders. Psychiatry Res 1996; 60:87–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar