Relationship of Gender and Age at Onset of Schizophrenia to Severity of Dyskinesia

Abstract

The authors examined severity of dyskinesia in 119 men and 44 women, comparing by gender those with late-onset schizophrenia (LOS) versus early-onset schizophrenia (EOS). Women with LOS and men with EOS had more severe dyskinesia than men with LOS and women with EOS. Many factors, including the length of neuroleptic treatment, alcohol and smoking history, and menopausal status, may contribute to the severity of dyskinesia in older patients with schizophrenia.

The role of gender in the development of tardive dyskinesia (TD) in patients with schizophrenia is not clear. A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies of patients of varying ages and diagnoses found that TD was more common in women;1 yet prospective studies of incidence of TD in older patients have found no gender difference.2,3 Some studies have found an interaction between gender and age. Under age 50, the prevalence of TD in women and men is similar. Between 51 and 70, however, more women than men are diagnosed with TD,1 suggesting a possibility that declining levels of estrogen associated with menopause increase the risk of TD.4

In most studies, the duration of treatment or the interaction between age and duration of treatment was not considered in conjunction with gender. TD develops after shorter periods of neuroleptic treatment when initiated later rather than earlier in life.2,3 Other differences exist between patients who manifest schizophrenia for the first time after age 45 (late-onset schizophrenia; LOS), than those with early-onset schizophrenia (EOS). Patients with LOS are more likely to be women; they have less severe negative symptoms, require lower doses of neuroleptic medication, and, obviously, have a much shorter duration of illness than patients with EOS.5 Furthermore, women with LOS have a different clinical presentation—specifically, less severe negative symptoms—than men with EOS or LOS or women with EOS.6 Therefore, comparing postmenopausal women with LOS not receiving hormone replacement therapy to men with LOS and men and women with EOS allows for an indirect test of the effects of estrogen loss on the manifestation of TD.

We examined the severity of TD in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, older than 45, who were treated with typical neuroleptics. We hypothesized that women with LOS would have more severe dyskinesia than men with LOS, women with EOS, or men with EOS, because of the loss of estrogen associated with menopause.

METHODS

Subjects included 163 outpatients ages 45 to 80 years from our Intervention Research Center (IRC) with a DSM-III-R or DSM-IV7,8 diagnosis of schizophrenia (n=133) or schizoaffective disorder (n=30). All subjects gave written informed consent for research participation. Eligible patients were on stable doses of typical neuroleptics for at least one month prior to enrollment. Only postmenopausal women participated, and none was receiving hormone replacement therapy. The sample was predominantly Caucasian (71.8%).

Medical and pharmacological history was obtained from each subject, corroborated by information from medical records and/or family members. Structured neurological and other physical examinations and appropriate laboratory evaluations were performed.

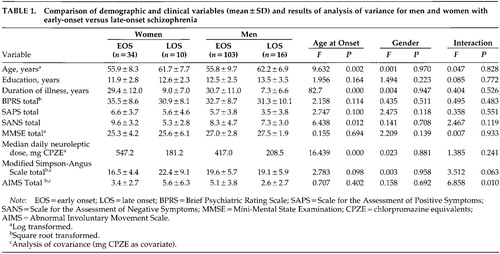

The following clinical rating scales were used: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),9 Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS),10 Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),11 modified Simpson-Angus Scale for extrapyramidal symptoms (SA-EPS),12 and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS).13 Interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient) ranged from 0.76 to 0.88. Duration of illness was used as a rough estimate of duration of neuroleptic treatment. All of the assessments were performed by trained raters blind to other clinical data and study hypotheses.

Two-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with between-group factors of gender and age at onset of schizophrenia (EOS vs. LOS) were performed to compare men and women on relevant variables. Analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were performed with the covariate daily neuroleptic dose (mg chlorpromazine equivalent; CPZE14) for SA-EPS and AIMS scores. When necessary, variables were transformed to meet the assumptions of normality. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

RESULTS

There were no significant effects of gender or age at onset or their interaction on education, BPRS, SAPS, or MMSE scores (Table 1). Women and men did not differ with respect to duration of illness. LOS patients were older, had a shorter duration of illness, and were on lower daily neuroleptic dose than EOS patients. The groups did not differ in the proportions taking anticholinergic medication, or in terms of physical comorbidity, including diabetes mellitus (data not shown). There was a significant main effect for age at onset of illness on the SANS score, and the interaction of gender and age at onset approached significance, with women with LOS having the least severe negative symptoms. Women with LOS had the highest SA-EPS scores, with the interaction effect approaching significance. There was a gender by age-at-onset interaction for the AIMS score, with women with LOS and men with EOS having more severe TD than women with EOS or men with LOS. The proportion of patients who met the criteria for the clinical diagnosis of TD,15 however, was similar for the four groups (women with EOS, 35%; women with LOS, 40%; men with EOS, 46%; men with LOS, 25%; χ2=3.065, P=0.382)

Because of significant age-at-onset effects on age, duration of illness, and neuroleptic dose, ANCOVAs were performed using age and mg CPZE or duration of illness and mg CPZE as covariates for SA-EPS and AIMS scores. The interaction effect for the AIMS score remained significant for both analyses. When covarying for age and mg CPZE, the effect of SA-EPS was no longer significant.

Results of a one-way ANOVA of the four groups with post hoc tests (Least Squared Differences) on the SA-EPS scale not covaried for age or CPZE showed that men with EOS had significantly higher scores on the SA-EPS than women with EOS (P=0.007) and that women with LOS had more EPS than women with EOS (P=0.038). Results of a one-way ANOVA of the four groups with post hoc tests (Least Squared Differences) on the AIMS not covaried for age or CPZE showed that men with EOS had significantly greater dyskinesia than men with LOS (P=0.008) and women with EOS (P=0.035), and that women with LOS had a trend toward having higher AIMS scores than men with LOS (P=0.096)

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that women with late-onset schizophrenia and men with early-onset schizophrenia had more severe dyskinesia than women with early-onset schizophrenia and men with late-onset schizophrenia, despite the remarkable similarity on most critical variables associated with TD and independent of differences in age, duration of illness, or daily neuroleptic dose. Most studies have noted that as the duration of illness (reflecting length of neuroleptic use) increases, the prevalence and severity of TD increase. Although this might explain the higher AIMS scores in men with EOS (mean duration of illness, 31 years), women with LOS had an average duration of illness of only 9 years, which was comparable to that of men with LOS (7 years). Therefore, the greater severity of dyskinesia in women with LOS must be attributed to something other than duration of illness. The marked decline in estrogen at menopause may put women who manifest schizophrenia later in life at a higher risk of more severe dyskinesia. Lower levels of estrogen have been associated with greater psychopathology in women with schizophrenia,16 and treatment with estrogen has been reported to decrease psychopathology.17 Some studies,18 but not others,19 have found that TD decreases with estrogen treatment. Women with EOS were also postmenopausal, yet they did not have AIMS scores as high as those of women with LOS. Whereas postmenopausal women with LOS and with EOS may both be at higher risk of developing more severe dyskinesia than men because of estrogen loss associated with menopause, the higher mean daily dose of neuroleptic seen in women with EOS may have masked dyskinesia that might otherwise have been present.

To better understand why men with EOS had elevated scores on the AIMS, we analyzed the proportion of patients who met DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria for past alcohol abuse or dependence, as well as smoking history. More men with EOS had histories of alcohol abuse or dependence (45%) than men with LOS (25%), women with EOS (22%), or women with LOS (11%). This difference was nearly significant (χ2=7.148, P=0.067). More men with EOS had ever smoked (84%) compared with the other three groups (54%, 63%, 63%, respectively) (χ2= 21.724, P=0.001). A history of alcohol dependence or abuse has been shown to be associated with increased risk of TD,2 and some, but not all, studies have found that smoking is related to the development of TD.20 Therefore, it is possible that the higher proportion of positive histories of alcohol and smoking use may have contributed to the higher AIMS scores in the men with EOS.

There are several limitations to our study. This was a cross-sectional study, and therefore it could only indirectly assess the relationship between estrogen and severity of dyskinesia. A longitudinal study of dyskinesia before and after menopause would test our hypothesis more directly. Second, the sample size for women, especially the LOS group, was small (n=10) because a Veterans Affairs Medical Center with a predominantly male patient population was a major site of patient recruitment. Finally, we relied on duration of illness as a proxy measure for length of neuroleptic treatment. Nonetheless, these results suggest that menopausal status, in addition to length of neuroleptic treatment and alcohol and smoking history, may contribute to the risk for developing severe TD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH43693, MH51459, MH45131, MH49671, MH01580; the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression; and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

|

1 Yassa R, Jeste DV: Gender differences in tardive dyskinesia: a critical review of the literature. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:701-715Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Jeste DV, Caligiuri MP, Paulsen JS, et al: Risk of tardive dyskinesia in older patients: a prospective longitudinal study of 266 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:756-765Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Saltz BL, et al: Prospective study of tardive dyskinesia in the elderly: rates and risk factors. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1521-1528Google Scholar

4 Seeman MV, Lang M: The role of estrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:185-194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Jeste DV, Symonds LL, Harris MJ, et al: Non-dementia non-praecox dementia praecox? Late-onset schizophrenia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 5:302-317Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Lindamer LA, Lohr JB, Harris MJ, et al: Gender-related clinical differences in older patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:61-67Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

8 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic Criteria from DSM-IV. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

9 Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:97-99Google Scholar

10 Andreasen N, Nasrallah HA, Dunn V, et al: Negative versus positive schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:789-794Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Simpson GM, Angus JW: A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 212:11-19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 534-537Google Scholar

14 Jeste DV, Wyatt RJ: Understanding and Treating Tardive Dyskinesia. New York, Guilford, 1982Google Scholar

15 Schooler N, Kane JM: Research diagnoses for tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:486-487Medline, Google Scholar

16 Hallonquist JD, Seeman MV, Lang M, et al: Variation in symptom severity over the menstrual cycle of schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 33:207-209Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Kulkarni J, de Castella A, Smith D, et al: A clinical trial of the effects of estrogen in acutely psychotic women. Schizophr Res 1996; 20:247-252Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Villeneuve A, Cazejust T, Cote M: Estrogens in tardive dyskinesia in male psychiatric patients. Neuropsychobiology 1980; 6:145-151Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Glazer WM, Naftolin F, Morgenstern H, et al: Estrogen placement and tardive dyskinesia. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1984; 10:345-350Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Yassa R: Other factors in the development of tardive dyskinesia, in Neuroleptic-Induced Movement Disorders, edited by Yassa R, Nair NPV, Jeste DV. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp 99-103Google Scholar