Level of Obsessionality Among Neurosurgical Patients With a Primary Brain Tumor

Abstract

Obsessive-compulsive symptoms have been associated with different types of damages or dysfunctions in the brain. However, the accumulated evidence on obsessive-compulsive symptoms among patients with a primary brain tumor is so far based on case reports only. The study population consisted of 59 neurosurgical patients with a primary brain tumor. One preoperative and two postoperative assessments for the level of obsessionality were done with the Crown-Crisp Experiential Index (CCEI)-instrument. Mean obsessionality scores increased significantly among the patients with a tumor in the left anterior region of the brain measured at 3 months after operation, especially in women, compared to the patients with a tumor in other regions of the brain. The level of obsessionality seemed to increase immediately after operation among patients with a primary tumor left anteriorly in the brain. This increase may be linked with the lesion caused by the tumor itself or the neurosurgical operation.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a disabling psychiatric condition characterized by recurrent and disturbing thoughts or images (obsessions) and repetitive and/or ritualistic or stereotyped behaviors that a person feels driven to perform (compulsions).1 Although the primary pathogenesis of OCD is uncertain2 OCD has been considered a neuropsychiatric disorder with altered neurological function.1 According to the literature, obsessive-compulsive symptoms have been associated with different types of brain damage or dysfunction as follows. Alegret et al (2001) reported that patients with severe Parkinson’s disease had more obsessive symptoms than normal population.3 Furthermore, obsessive-compulsive symptoms have been found in postencephalitic patients.4 There are case reports of obsessive-compulsive disorder associated with pediatric cerebral malignancies.5,6 In the case reports of adult patients’ feelings the onset of obsessive-compulsive symptoms has been considered to be a sign of underlying organic pathology of a primary brain tumor7,8,9 or head trauma.10,11 Recently Stengler-Wenzke et al.12 suggested that secondary OCD is caused by brain injury in the fronto-orbito-striatal region,12 and Stein (2002) reported that functional imaging studies have found altered activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and caudate, especially during exposure to feared stimuli among OCD patients.1

To our knowledge, there are no population based clinical studies assessing the obsessive and compulsive symptoms among patients with a brain tumor. Thus, it can be hypothesized that secondary OCD is strongly present among brain tumor patients who have brain dysfunction and who are at the same time afraid of the operation associated with their severe disease and exposed to fear of dying. We investigated the level of obsessionality among brain tumor patients with preoperative and postoperative measurements by taking into account also the location and histology of the tumor.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients and Tumors

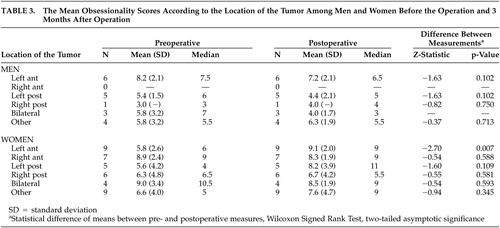

The original prospective study population consisted of 101 consecutive patients with a solitary primary brain tumor treated surgically at the Oulu Clinic for Neurosurgery, Oulu University Hospital in Northern Finland. Epidemiologically the cohort is a comprehensive and unselected sample of population, because the Oulu Clinic for Neurosurgery performs all resections of brain tumors in its catchment area. Geographically this area covers about 49% of Finland. The sociodemographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The Ethics Committee of Oulu University Hospital approved the study protocol. The patients were studied preoperatively with CT or MRI to determine the location of the tumor. The histology of the tumor was defined according to the WHO classification.13 There were 19 grade I-II gliomas, 22 grade III-IV gliomas, 33 meningiomas, 8 pituitary adenomas, 13 acoustic neurinomas and 6 other tumors (two hemangiopericytomas, malignant lymphoma, craniopharyngeoma and two undefined tumors). The tumors were divided into ones located in the left or the right hemisphere or bilaterally and anteriorly or posteriorly, as described in the study by Salo et al (2002).14 There were 45 patients with a tumor in the left hemisphere, 34 patients with a tumor in the right hemisphere and 14 patients with a tumor located bilaterally. Thirty eight patients had a tumor anteriorly and 26 patients had a tumor posteriorly in the brain.

The data used in this study were divided into six groups according to the anatomical location of lesions as follows: left anterior, right anterior, left posterior, right posterior and bilateral location. The sixth group i.e. “others” consists of the patients for which information on either the left/right or anterior/posterior location was lacking. The number of subjects for whom all three assessments for obsessionality were available was 59 patients (19 men, 40 women).

Assessment of Obsessionality

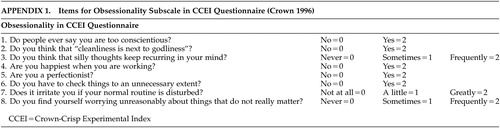

The level of obsessionality was measured in one preoperative assessment (before surgery) and two postoperative assessments (3 months and 1 year after surgery). The scores of the obsessionality subscale of the Crown-Crisp Experiential Index (CCEI), earlier called the Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire, were used.15 According to Crown and Crisp, CCEI has been formulated for three different purposes: to describe normal and deviant groups, to study psychosomatic interrelationships, and as a clinical psychometric test to study personality change following either psychological or somatic therapies.16 CCEI has been used in studies on patients with psychiatric17 or somatic diseases18 and in studies screening normal population to find neurotic psychopathology.19

The obsessionality scale consists of eight items, each of which can be scored 0, 1 or 2 (Appendix 1).16 The sum of these scores (0-16) is used to assess the level of obsessionality, i.e. psycho-pathology of obsessive-compulsive disorder among the patients.15 The norms (mean and SD) for obsessionality are 6.3 (3.9) for men and 6.2 (2.7) for women among normal population, 6.8 (2.8) for men and 7.4 (2.9) for women among patients in general practice, and 8.7 (3.5) for men and 8.2 (3.8) for women among psychoneurotic out-patients.15,20 In these studies, the differences in obsessionality scores between the genders were not statistically significant. The obsessionality scale has been suggested to differentiate normal subjects and psychoneurotic patients at a statistically highly significant level.16 CCEI has also been validated for the Finnish population.21

Statistical Analysis

The group differences in categorical variables were assessed with Pearson’s Chi Square Test. The results of continuous variables are given as means, medians and standard deviations (SD). An analysis of covariance method (ANCOVA) was used to assess the gender difference in mean obsessionality score after controlling for age of the patient, as well as the size and the histology of the tumor. Otherwise, independent samples Mann-Whitney U-Test were used for group comparisons due to the small sample size and skewed distribution of the variables. Changes in individual scores between measurements were assessed with Wilcoxon signed ranks test or Friedman Test when appropriate. The statistical software was SPSS version 10.

RESULTS

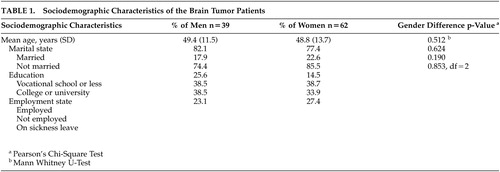

Table 2 shows the mean obsessionality scores and the results of gender comparisons in one preoperative and two postoperative assessments. Before tumor operation the mean obsessionality scores were 6.3 (SD 2.9) for men and 6.9 (SD 3.9) for women (no gender difference). Three months after surgical resection of the tumor, the mean obsessionality scores among women were statistically significantly higher 8.1 (SD 3.3) compared to the scores among men 5.6 (SD 2.2), (ANCOVA, p=0.003). A corresponding difference was seen also at 1 year after operation (ANCOVA, p=0.026).

When analyzing the change in individual score between three assessments of obsessionality, the increase in scores was statistically significant in women (Friedman Test, p=0.036). An opposite finding—a slight decrease in obsessionality scores between assessments—was seen in male patients, although the change indicated only a trend towards significance (Friedman test, p=0.097).

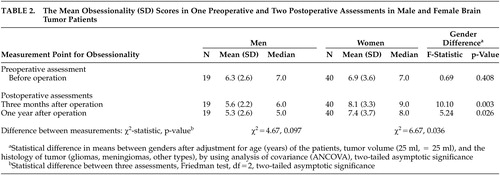

Table 3 shows the mean obsessionality scores according to the location of the tumor in preoperative assessments and 3 months postoperatively among male and female patients. The results of comparisons between preoperative assessments and those made 1 year postoperatively are not reported, since no statistically significant changes were observed between assessments made 3 months and 1 year after the operation in any of the comparisons according to gender and the location of the tumor.

In the female patients with a primary brain tumor in the left anterior hemisphere, a statistically significant increase in the level of obsessionality was observed between pre- and postoperative measurements (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p=0.007). No significant change in the level of obsessionality was seen if the tumor was located in any region other than the left anterior region in women and in any location in male patients.

DISCUSSION

Based on neurosurgical patients with a primary brain tumor, our main finding was that the mean obsessionality scores in women increased statistically significantly between measurements before operation and 3 months after operation compared to men. The differences remained significant until 1 year of follow up. The increased obsessionality scores in women reached scores indicating neurotic psychopathology of OCD.

According to Crown15 and Crisp et al20 there were no gender differences in the values of obsessionality in different study populations. Also, according to epidemiological studies the prevalence of OCD is roughly equal in men and women.1 On the contrary, Zohar et al (1999) reported on sexual dimorphism of OCD.22 In their opinion there are putative data showing that OCD is differently expressed in the two sexes and that the etiology of OCD might be different in the two genders. Thus, our finding of a statistically significant difference in the level of obsessionality between the genders is a novel and important finding and further studies on these topics are needed.

Another main finding in our study was that the increase in the level of obsessionality was statistically significant in women if the tumor was located in left anterior hemisphere. Previous case reports of male and female patients have stated that obsessions or compulsions were linked with lesions caused by brain tumor in frontal regions of the brain.7,9 Our results support these case reports in relation to obsessionality and neuroanatomic brain location of the tumors. This is the first time so far that these preliminary findings published in case reports have been confirmed in a representative clinical patient sample.

Ward (1988) suggested that a focal cerebral disturbance could cause OCD that had earlier been considered to be purely psychological in etiology.7 Nowadays OCD is considered to be a neuropsychiatric disorder in which altered function in the prefrontal-basal ganglia-thalamic-prefrontal circuits is particularly important.23 Functional imaging has shown that OCD is characterized by increased activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and in basal ganglia at rest and especially during exposure to feared stimuli.24 Furthermore, Tot et al (2002) found that patients with OCD had left frontotemporal dysfunction recorded by quantitative electroencephalography (QEEG), especially in women.25

In this study we were able to study subjects who simultaneously had brain dysfunction caused by a tumor, underwent surgery, and at the same time were probably frightened and worried. The pathophysiology of OCD has been linked with serotonin metabolism26 and with metabolism of stress neuropeptides such as arginine vasopressin, corticotrophin releasing hormone, somatostatin and oxytocin.27 However, there are a few studies on transmitters or neuropeptides related to brain tumors. Some studies have linked high levels of somatostatin receptors with gliomas and meningiomas.28,29 In our study no information was available about biochemistry, i.e. the levels of stress hormones, serotonin or somatostatin in the patients. Thus, in further studies of the psychiatric disorders among brain tumor patients it is important to define the content of these transmitters and neuropeptides and to determine the density of these receptors on tumors.

The limitations of our study were that we could not evaluate the previous psychiatric history or premorbid personality of the patients. The fact that the number of cases in every subgroup was rather small was also a limitation of our study, although our database is a representative and unselected sample of the population in Northern Finland. Unfortunately the study protocol did not include an assessment of the exact psychiatric diagnosis according to any structured criteria-based diagnostic interview. Our tool of CCEI is a rough scale for measuring OCD and thus our findings are only suggestive in nature. New research is needed in which the diagnosis of OCD is confirmed by a structurized and standardized interview by a psychiatrist.

In summary, it is to our knowledge that this is the first study in which the occurrence of obsessionality among patients with a primary brain tumor has been studied in a representative sample of the population of a geographical area. We suggest that among patients with a primary brain tumor the level of obsessionality is associated with the removal of tumor in women, and especially if the tumor is located anteriorly in the brain. We emphasize also the important clinical aspect of this study: it is important to evaluate separately possible OCD symptoms because the patients are usually aware that their thoughts and behavior are strange, feel ashamed and try to hide their obsessions and compulsions.26 Since increased obsessionality was found immediately, as early as 3 months after surgery, these psychiatric symptoms ought to be already evaluated in neurosurgical units. It is also known that if OCD can be prevented it has a positive effect on the patients’ quality of life.

|

|

|

|

1 Stein DJ: Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet 2002; 360:397–405Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Stein DJ: Neurobiology of the obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47:296–304Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Alegret M, Jungue C, Vallderiola F, et al: Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 70:394–396Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Cheyette SR, Cummings JL: Encephalitis lethargica: lessons for contemporary neuropsychiatry. J Neuropsych Clin Neurosci 1995; 7:125–135Link, Google Scholar

5 Peterson BS, Bronen RA, Duncan CC: Three cases of symptom change in Tourette’s syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder associated with paediatric cerebral malignancies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 61:497–505Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Mordecai D, Shaw RJ, Fisher PG, et al: Case study: Suprasellar germinoma presenting with psychotic and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:116–119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Ward CD: Transient feelings of compulsion caused by hemispheric lesions: three cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988; 51:266–268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Paradis CM, Friedman S, Hatch M, et al: Obsessive-compulsive disorder onset after removal of brain tumor. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:535–536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 John G, Eapen V, Shaw GK: Frontal glioma presenting as anxiety and obsessions: a case report. Acta Neurol Scand 1997; 96:194–195Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 McKeon J, McGuffin P, Robinson P: Obsessive-compulsive neurosis following head injury: a report of 4 cases. Br J Psychiatry 1984; 144:190–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Berthier ML, Kulisevsky JJ, Gironell A, et al: Obsessive-compulsive disorder and traumatic brain injury: behavioral, cognitive, and neuroimaging findings. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2001; 14(1):23–31Medline, Google Scholar

12 Stengler-Wenzke K, Müller U: Fluoxetine for OCD after brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(5):872Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Kleihues P, Burger PC, Scheithauer BW: Histological typing of tumors of the central nervous system. WHO Classifications 2nd ed. Berlin, Springer Verlag 1993Google Scholar

14 Salo J, Niemelä A, Joukamaa M, et al: Effect of brain tumor laterality on patients’ perceived quality of life. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72:373–377Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Crown S: The Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire (MHQ) in clinical research. A review. Mod Probl Phamacopsychiat 1974; 7:111–124Medline, Google Scholar

16 Crown S, Crisp AH: A short clinical diagnostic self-rating scale for psychoneurotic patients. Br J Psychiat 1966; 112:917–923Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Elliott SA, Leverton TJ, Sanjack M, et al: Promoting mental health after childbirth: a controlled trial of primary prevention of postnatal depression. Br J Clin Psychol 2000; 39:223–411Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Haines A, Cooper J, Meade TW: Psychological characteristics and fatal ischaemic heart disease. Heart 2001; 85:385–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Lindeman S, Hirvonen J, Joukamaa M: Neurotic psychopathology and alexithymia among winter swimmers and controls—a prospective study. Int J Circumpolar Health 2002; 61:123–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Crisp AH, Gaynor Jones M, Slater P: The Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire: A validity study. Br J Med Psychol 1978; 51:269–280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Joukamaa M: Crown-Crisp Experiential Index, a useful tool for measuring neurotic psychopathology. Nord J Psychiatry 1992; 46:49–53Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Zohar J, Gross-Isseroff R, Hermesh H, et al: Is there sexual dimorphism in obsessive-compulsive disorder? Neurosc Biobehav Rev 1999; 23:845–849Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Insel TR: Toward a neuroanatomy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:739–744Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Rauch SL, Savage CR: Neuroimaging and neuropsychology of the striatum. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1997; 20:741–768Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Tot Ş, Özge A, Çömelekoğlu Ü, Yazici K et al: Association of QEEG findings with clinical characteristics of OCD: Evidence of left frontotemporal dysfunction. Can J Psychiatry 2002; 47:538–545Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Hollander E: Treatment of obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders with SSRIs. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173(suppl 35S):7–12Google Scholar

27 Baumgarten HG, Grozdanovic Z: Role of serotonin in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173(suppl 35S):13–20Google Scholar

28 Held-Feindt J, Krisch B, Mentlein R: Molecular analysis of the somatostatin receptor subtype 2 in human glioma cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1999; 64(1):101–107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Cavalla P, Schiffer D: Neuroendocrine tumors in the brain. Ann Oncol 2001; 12(suppl 2):131–134Google Scholar