Tourette’s Syndrome and the Law

Abstract

Diminished legal responsibility and mental capacity have been used in defense of individuals with neurological disorders charged with legal misdemeanors, including criminal behavior. The purpose of this report is to 1) critically examine the mechanisms that may predispose patients with Tourette’s syndrome (TS) to potentially, legally liable behaviors; 2) report the results of a nation-wide review of state, federal, and appellate cases involving TS; and 3) instigate awareness within the professional legal community regarding unrecognized organically-based behaviors that may predispose TS patients to unwanted legal disciplinary action. TS is a common neurological movement disorder of childhood onset associated with behavioral comorbidities, including impulse control problems, exhibition of obscene language or gestures, rage attacks, inappropriate obsessions, and other behaviors. To our knowledge, there are no studies (to date) addressing the potential impact of TS on the legal system. A comprehensive review of the neurobehavioral mechanisms underlying comorbid issues in TS is outlined. A comprehensive review of all cases tried in state and federal courts between 1985 and 2003, in which TS was somehow implicated, was conducted using the Westlaw database. As of October, 2003, TS was implicated in more than 150 cases found in the federal and state databases, 21 of which were criminal. Other cases are categorized as civil rights, criminal, education, family, labor, and social security cases. The authors conclude that TS rarely leads to criminal behavior, but patients with TS who have behavioral comorbidities are at risk of being involved with the legal system. The medical-legal community must learn to recognize the vulnerability of this patient population to potential mistreatment by the courts of justice.

Cesare Lombroso, the 19th-century Italian criminologist, was among the first to claim that criminals were born and not made, establishing the notion that an unlawful behavior may result from the genetic makeup of the offender, rather than the volitional intent of the individual.1 There has been growing support for this notion from the scientific literature, linking certain neurobiological conditions, including epilepsy, frontotemporal dementia, schizophrenia, and posttraumatic brain injuries to criminal behavior as a result of involuntary, unwanted disinhibitions (e.g., rage, violence, or other socially inappropriate behavior).2–5 The use of “diminished legal responsibility” and “diminished capacity” are relevant in such cases, as they focus on specific intent as an element of determining guilt and degree of punishment.

The use of an organic medical condition to determine causality of a crime committed requires not only understanding of the underlying neurobehavioral mechanisms by the qualified medical or scientific professional, but also awareness of such a basis within the professional legal community. The dynamics underlying delinquent behavior have been attributed to a mixture of environmental, genetic and social causes. Brain imaging studies used to investigate the neurobiology of criminal behavior have suggested abnormalities in the amygdala, hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex of murderers.6–8 Prefrontal hypoperfusion and decreased glucose uptake in the prefrontal cortex have been associated with impulsiveness and aggressive, violent behavior.9–11

Tourette’s syndrome (TS) is one such disorder where ignorance of the organic basis resulted in social ostracism and injustice for the patients suffering from the disorder. Considered a psychogenic disorder until successfully treated in the 1960s with dopamine receptor blocking agents (neuroleptics),12 severe TS patients were committed to mental institutions due to misunderstanding of the syndrome. TS is now recognized as one of the most common genetic neurological disorders of childhood onset, affecting, variably, up to 3.8% of all children.13,14 However TS continues to be frequently unrecognized and poorly understood by both the lay community and health care professionals alike, partly due to its complex and often bizarre neurobehavioral and motor phenomenology.

Characterized neurologically by involuntary motor and phonic tics, TS is commonly associated with neurobehavioral comorbidities such as attention deficit disorder (ADD), attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), disinhibition of aggression and emotions, mood disorders, and poor impulse control.14–18 Medical research supports TS as a disorder of disinhibition, manifested as various phenomena including the motor tics and phonic tics as well as socially inappropriate vocal utterances, including cursing, profanities, and obscenities (coprolalia), and the less recognized disinhibitory symptoms such as poor impulse control, addiction, exhibitionism, and rage attacks. These neurobehavioral symptoms have been attributed in part to a dysfunction of the cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical circuitry19 involving various neurotransmitters such as dopamine, gamma-amino-butyric-acid (GABA) and serotonin.20 TS is considered one of the most complex human conditions, and diagnosis, treatment, and management of the disorder requires the expertise representing a broad range of disciplines including neurology, psychiatry, psychology, sociology, and education.

To date no controlled studies have investigated the prevalence of disinhibitory behaviors leading to legal action in the TS population. The purpose of this study is to 1) critically examine the mechanisms that may predispose the TS population to potentially legally liable behaviors, 2) report the results of a nation-wide review of appellate cases involving TS and 3) instigate awareness within the professional legal community in regards to organically based behavior which may predispose TS patients to legal disciplinary action.

METHOD

A comprehensive review of the neurobehavioral mechanisms underlying comorbid issues in TS is outlined. Furthermore using the Westlaw database, a comprehensive review of all cases tried in state and federal courts between 1985 and 2003 in which TS was somehow implicated was performed.

TS and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and Addictive Behavior

It is well established that TS is commonly associated with ADHD and OCD.15,16 OCD, present to a variable degree in a majority of TS patients,17,21 is characterized by symptoms of recurrent thoughts or images (obsessions) or behaviors (compulsions) interfering with daily activity.22 Several studies have concluded that TS-related OCD differs from idiopathic OCD in that obsessions seen in idiopathic OCD, such as fear of contamination, germs or cleanliness are uncommon in patients with TS. Rather, obsessions and ritualistic behaviors with “just right” themes, or a need for completion, symmetry, and perfection predominate in TS patients.23 Repetitive, intrusive thoughts are also more common in TS patients, with fear of death of self or others.24 A strong component of ritualistic behaviors without secondary gain are common in TS patients with OCD features.

Addictive behavior, sometimes leading to dependence on alcohol, drugs, gambling and sexual abuse, may be seen in severe TS cases.25,26 The APA defines addiction or dependence as the “compulsion to consume with a loss of limiting intake.”22 Dysregulation of various neurotransmitters such as dopamine for reward seeking behaviors and serotonin for desensitization in the mesocorticolimbic system have been implicated in addiction and substance abuse.27,28 Studies using 5HT1B receptor gene knockout mice have suggested that serotonin may play a role in addictive behavior, aggression, and impulsivity.29 When compared to the wild-type mice, the 5HT1B knockout mice displayed more intense, frequent and rapid attacks against intruder mice. Knockout mice were also found to self-administer cocaine and ingest ethanol at increased rates when matched against comparison subjects.30 Tryptophan depletion in healthy males showed an increase in aggression in one study, supporting that low tryptophan concentration and altered brain serotonin levels result in aggressive behaviors.31

TS patients may also develop a physiological need for other illegal substances such as marijuana or other cannabinoids, due to both the pure physiological pleasure and reward, and their beneficial impact on tics. In one study of 64 TS patients, 14 of 17 (82%) reported that marijuana reduced motor and phonic tics, decreased premonitory sensations (the urge to tic) and improved OCD symptoms.32 A high density of cannabinoid receptors has been found in the basal ganglia and hippocampus in brains of patients with various hyperkinetic movement disorders.33 Several other neuroimaging studies using structural and functional imaging techniques have provided support for altered cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical circuity in TS.34,35

TS and Impaired Impulse Control

Poor impulse control is another neurobehavioral feature in TS patients that may result in negative psychological, social and possibly legal consequences. Poor impulse control may manifest as acting before thinking, often including acts of physical abuse and other acts of unpremeditated violence. Impulsivity represents a serious public health problem because it is often associated with aggression, violence, and criminality leading to increased morbidity; mortality; social, family, and job dysfunction; and excessive use of health care, government, and financial resources.36

Several animal studies support the organicity of impulsive behavior. Animal studies of rats with lesions of the nucleus accumbens, the brain region noted for reward and reinforcement, showed that the lesioned rats preferred small, immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards, supporting an impulsive, immediate response.37 Furthermore, the lesioned rats showed locomotor hyperactivity, possibly reflecting ADHD comorbidity. Afferents to the nucleus accumbens include the anterior cingulate cortex, medial, orbitofrontal and ventromedial prefrontal cortices. However, lesions in the anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortices did not induce impulsivity, implying the necessary contribution of the latter two prefrontal cortices in causing impulsive behaviors. Lesions in the ventromedial prefrontal cortices and in the amygdala have also been known to result in altered decision making processes and a disregard for future consequences.38

Human studies measuring metabolism and blood flow in TS subjects using positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) have consistently reported hypometabolism of various areas in the basal ganglia and temporolimbic pathway, specifically the anterior cingulate, parahippocampal and insular cortices. These areas are thought to be associated with executive functions, impulse control and inhibition of unwanted behavior.39 Using carbon-11 Raclopride PET and amphetamine stimulation, Singer et al.,40 found evidence for increased dopamine release in the putamen of patients with TS. They postulate that in TS there is increased activity of the dopamine transporter leading to increased dopamine concentration in the dopamine terminals and stimulus-dependent increased in dopaminergic transmission. Support for this hypothesis has been provided by the imaging studies of Albin et al.41 The authors used PET with the type 2 vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT-2) ligand [11C]dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) to quantify striatal monoaminergic innervation in patients with TS (N=19) and control subjects (N=27). With voxel by voxel analysis, the investigators found increased DTBZ binding in the ventral striatum (right>left) in patients with TS as relative to age-matched comparison subjects.

TS and Disinhibition

TS has been hypothesized to be a spectrum disorder of involuntary disinhibitions. Disinhibitions manifest behaviorally as acts of aggression, explosive emotional outbursts, and rage attacks which are often associated with verbal and physical abuse toward others.42,43 The neuropathological mechanisms of these uncontrollable behaviors are unknown, although lesions of the basolateral amygdala as well as the orbitofrontal cortex have been associated with increased emotional reactions to external stimuli.43,44

In younger children, emotional disinhibition may manifest as temper tantrums and self-injurious behavior. Anger outbursts occasionally leading to rage attacks may force frightened parents or other family members who are victims of these violent rages to contact law enforcement officials. In severe TS cases, patients who hit, choke or throw objects uncontrollably with extreme emotions of anger and frustration are common testimonies of TS parents, coworkers and peers. A pilot study of 12 TS patients with “rage attacks” showed that all subjects had both comorbid ADHD and OCD.43 Two patients were also diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder, and 4 with conduct disorder based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM–IV.

The phenomenon of rage attacks serves as a model for how various TS comorbidities may integrate to synergistically produce a harmful behavioral response. For instance, patients, as part of their OCD, may persistently dwell on inaccurate or misperceived negative criticism and subsequently formulate an exaggerated emotional response. TS patients with rage attacks often ruminate on intrusive thoughts and may emotionally react with socially inappropriate behaviors. One study of 87 TS patients (adolescents and adults) reported 30% had an urge to insult others and 26% had an involuntary urge to make socially inappropriate comments.45 The majority of patients, however, reported a desire to suppress these inappropriate behaviors and frequently expressed remorse to the victims. In a desperate effort to help his son with TS, one of our patient’s father called the police after his son choked him while he was driving. During a clinic interview, the patient reported symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder, a psychiatric condition within the spectrum of OCD. He persistently thought about how “ugly” he was as he looked in the mirror, and directed his anger toward his father. His father confirmed that he ritualistically looked in the mirror and verbally repeated negative thoughts to himself. In another example, a boy with TS obsessed about monster movies and stories while pretending to be a monster while physically attacking his siblings and parents.

TS patients may exhibit other disinhibitive phenomena including coprolalia, copropraxia and exhibitionism. Such behaviors are often misconstrued as volitional. Ten to 20% of TS patients suffer from coprolalia, the involuntary utterances of obscene words or profanities. Another 20% of TS patients experience mental coprolalia, a condition in which utterances are suppressed by patients who “think” obscene or profane words or phrases.46 The unwanted nature of coprolalia is exemplified by one of our patients who poignantly noted that after each such inappropriate utterance, he wanted to reach out and “bring the bad word back inside his mouth.” Functional neuroanatomy studies support increased metabolic activity in the orbitofrontal cortices in TS patients with neurobehavioral features such as obsessive compulsive traits, impulsivity, coprolalia, self-injurious behavior, and echophenomenon.9 Other metabolic imaging studies in patients with TS show abnormalities in frontal cortical areas, insula, and caudate nucleus as well as other areas involved normally in the inhibition of unwanted behavior.47 Mutations in genes coding for monamine oxidase A (MAO-A), a mitochondrial enzyme which oxidizes 5HT, dopamine and norepinephrine, have also been implicated in disinhibitory behavioral disorders.29 A MAO-A X- linked hemizygous chain termination mutation has been associated with episodes of exhibitionism, hypersexual behavior, and impulsive aggression in affected males from a large single family.48 MAO-A deficient knock out mice had elevated 5HT, dopamine and norepinephrine levels with associated aggressive behavior, hyperactive startle, increased stress response and violent sleep behavior.49 Despite the recent discovery of a rare gene mutation on chromosome 13 causing TS,50 there are currently no DNA tests available for this disorder. Even if such DNA tests were available, it is an appalling notion to consider genetic testing to screen individuals with potentially impulsively aggressive behavior as suggested by Yen in the following statement: “… the state might want to protect others from individuals with Tourette’s.” “Thus, a state might want to mandate genetic testing so that it could separate people with Tourette’s, who appear more prone to aggression, from the general population.”51

TS and Conduct Disorders

A database of 3,500 patients with TS evaluated in 64 neurological and psychiatric academic centers showed that 15% of patients have troublesome conduct and oppositional defiant disorder.52 One study compared conduct in 246 TS patients to controls for behaviors such as lying, stealing, fighting or inability to stop fighting, violence against animals, physically attacking peers or parents, vandalism, running away from home, starting fires, poor temper control, alcohol and drug abuse, or other misdemeanors against the law.53 Thirty-five percent of TS patients had a conduct score of higher than 13, significantly greater than the 2.1% in controls (p<0.0005). All behaviors with the exception of running away from home and the law variable were significantly greater in TS patients. The law variable was defined as previous trouble with the law. Although no difference was found for the law variable, TS patients were significantly more likely to vandalize (p<0.0005), fight (p<0.0005), abuse drugs or alcohol (p<0.003) and steal (p<0.015). An interesting finding in this study was that certain behaviors such as starting fires, shouting and physically attacking were only significantly greater in TS patients with comorbid ADD supporting the well established association of ADD and conduct disorder.54 Since the total conduct score in TS patients without ADD was significantly greater than that for comparison subjects (p<0.025) and the total conduct score for patients with TS and ADD was significantly greater than that for patients with pure ADD (p<0.05), the study supports the implication that TS patients were at higher risk of conduct problems than those with ADD only or normal controls.

TS and the Law

An estimated 2.5 million juveniles are engaged in criminal and unlawful activities each year55 and as of December 31, 2002, there were over 2 million prisoners held in Federal or State prisons or in local jails.56 It has been estimated that one in six of prisoners is mentally ill and the rate of mental illness in the prison population is three times higher than in the general population.57 Patients with TS and coexistent ADHD are at an increased risk of socially unacceptable and potentially criminal behavior,58,59 and, therefore, a review of cases of TS involved in the legal system is warranted.

A careful examination of this issue is particularly relevant because the disorder is often misrepresented in the media and lay press, wrongly attributing violent criminal behavior as intentional in certain individuals with TS. One retrospective study of 126 juveniles sentenced for serious offenses showed that 15% had a confirmed diagnosis of ADHD, 15% had a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD), and 2% had TS.60 However, this study reported that most offenders were referred to the forensic psychiatric investigation for serious offenses. Crimes committed by TS patients, however, are more likely to be minor offenses dismissed prior to reaching the level of legal investigation.

To date there have been no controlled studies investigating the prevalence of behaviors leading to unlawful minor or serious criminal offenses in the TS population, compared to the age-matched general population. From 1993 to 2003, 25,303 of 27,192 juveniles incarcerated in the Texas Youth Commission have been examined for psychiatric disorders. Of those examined 14, 13 males and one female, or 0.06% were diagnosed with TS. (Personal communication, Chuck Jeffords, Research Director, Tex. Youth Commission). Most criminal cases, however, are resolved before or at the trial level (without any appellate record), and therefore the reported cases represent only a tip of the iceberg. Several of our TS patients with severe comorbid behaviors and unwanted behaviors, such as verbalization of profanities or poor impulse control, have been charged with an assault on or retaliation by police officers during arrests for unrelated charges, such as speeding. There are many other examples of TS-related behavior leading to an encounter with the criminal justice system. The presence of organically based behaviors may be important to acknowledge during litigation of such cases. A review of case law suggests that diminished capacity has been allowed only in a few jurisdictions and under specific circumstances and evidence of mental weakness short of legal insanity is seldom admissible at the guilt-innocence phase of the trial.

RESULTS

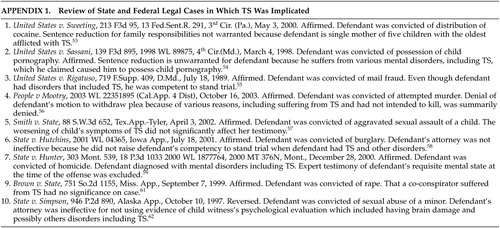

A review of the medicolegal literature yielded a paucity of studies on TS and law. As of October, 2003, TS was implicated in over 150 cases found in the Westlaw federal and state databases, 21 of which were criminal. The other cases could be categorized as civil rights, criminal, education, family, labor and social security cases. The oldest federal case reported was from 1987 while the oldest state case reported was from 1985. Of the 21 criminal cases in which TS was somehow implicated, there are 10 that are relevant to the topic of possible relationship between TS and criminal behavior (Appendix 1).61–71

In addition to the above cases there are other relevant cases drawing attention to the issue of TS and law. In the United States v. Hall72 the appellate court, in dicta, provided an excellent example of when a defendant’s TS may be relevant in a criminal case. Although the appellate issue focused on when medical expert testimony is necessary, the court stated, “Expert testimony may be particularly important when the facts suggest a person is suffering from a psychological disorder. Suppose, for example, it were relevant for a jury to decide whether a person’s use of foul or abusive language was intended to harm another. Most of the time, the jury would be able to assess the circumstances without the need for expert testimony, since foul language is an unfortunately part of everyday life. In some cases, however, the individual might be suffering from Gilles de la TS, which is a rare disorder manifested by grimaces, grunts and in about half of all cases the use of foul language. A defendant wishing to explain his behavior by showing he had TS would need expert testimony on both the condition itself and his own affliction.” This type of case more than likely would be resolved at the trial level, without an appeal, but it draws attention to the need to be aware of potential and unique issues that might arise for a TS patient in the criminal justice system. Better understanding of defendants’ organically based behavior may prevent unwarranted convictions or incarceration.

DISCUSSION

“Diminished capacity” is not a widely recognized legal principle. Every criminal offense requires the defendant to have a culpable mental state. Similarly, “voluntariness” may be an issue for a defendant with TS. In the United States v. Daniel Dzialo73 case, the defendant was convicted of conspiracy to distribute cocaine, but the court denied his motion to suppress evidence because the defendant claimed that the police illegally obtained his statement. The defendant alleged that he suffered from TS, causing him to involuntarily blurt out matters that were contained in his mind. The court did note that while testifying Mr. Dzialo exhibited various movement and vocal tics and repeatedly emitted animal like squeals. The court based its denial on a review of the relevant literature that failed to provide any evidence that TS might cause its victims to confess to criminal activity. The court went on to state that even if TS somehow impaired Mr. Dzialo’s cognitive or volitional capacity, this was not sufficient, by itself, to conclude that his statements were involuntary for the purposes of due process.

On April 23, 2002, the appellate court reversed and remanded People v. Michael Lempicki.74 Defendant was charged with criminal sexual conduct. He moved to suppress his statements made at the time of his arrest and the subsequent complainant’s statements because, in additional to other reasons, he did not knowingly, intelligently and voluntarily waive his Miranda rights and these statements were from the fruits of an illegal arrest. At the hearing on his motion, the prosecution and defense stipulated that the defendant was unable to knowingly, intelligently and voluntarily waive these rights. A report by a psychologist was admitted which stated defendant was diagnosed with autism at the age of five and suffered from TS. It further indicated defendant‘s adaptive skills fell significantly below cognitive levels and defendant‘s intellectual testing placed him at a mildly impaired range of functioning. According to the report, defendant‘s word recognition was at a first grade level and is suggestible and vulnerable to manipulation by others. The trial court concluded the police engaged in misconduct by interviewing defendant after observing his mental limitations. It then granted defendant’s motion suppressing his statements given to the police officer at the time of his arrest as well as the complainant’s statements because it was derived from the defendant’s illegally obtained statement. The appellate court recognized that both prosecution and defendant agreed he could not competently waive his Miranda rights. Contrary to the trial court and agreeing with the prosecution, it held that since the police had probable cause to arrest him, defendant’s arrest was legal. The appellate court also held even though defendant’s post arrest statement was illegally obtained, the derivative testimonial evidence of the victim discovered as a result of defendant’s confession was still properly admitted into evidence.

In a federal case United States v. Santo Rigatuso,75 the defendant was indicted on 12 counts of mail fraud and entered a plea of not guilty. The issue before the appellant court was the issue of defendant’s competency to stand trial. Defendant had been psychiatrically evaluated by a government psychiatrist and one retained by defendant. The federal standard for determining competency to stand trial prohibits trial if the court finds that the defendant is presently suffering from a mental disease or defect rendering him mentally incompetent to the extent he is unable to understand the nature and consequences of the proceedings against him or to assist properly in his defense. The prosecution’s expert testified that defendant has three disorders: 1) obsessive compulsive disorder; 2) narcissistic personality disorder with histrionic features; and 3) TS. He conceded defendant suffers some degree of impairment but this did not infringe upon his ability to relate in an effective manner. Although the defendant’s expert arrived at the same disorders as the prosecution’s expert, he testified that the defendant’s behavior is marked by 18 traits. The defendant’s expert summarizes the behavior as: 1) speech problems marked by excessive expression and lacking detail; 2) preoccupation with how well he is doing; 3) cannot see the forest from the trees; and 4) stubborn insistence. Although both experts agree defendant suffers from mental disorders, they disagree on the issue of whether the disorders make defendant incompetent. The court found defendant had sufficient present ability to consult with his lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding and, therefore, was competent to stand trial. The court noted it does not dispute defendant had TS, but in its observations, defendant’s tics are not remarkable in nature and degree. While he did twitch in the mouth and nose area on a regular basis, it was not the type of activity that would cause people to stare at him. The court held finding a defendant competent simply because he passes his attorney a few notes during the competency hearing, or because his nervous tics as the result of TS seems much less severe than anticipated, would border in an abuse of discretion. In the same view, finding a defendant competent on the strength of a federal judge’s “gut” reaction would also be tenuous. But it would be equally abusive to find defendant incompetent because his past and present attorneys find him frustrating to work with. Therefore, the court found defendant competent because he can assist his attorney and assist in his defense.

In another case, defendant Mr. Al Armein was convicted of stalking and 19 other various misdemeanors in Superior Court of San Diego, California. In a not officially published opinion People v. Almed Al Armein,76 the appellate court held on May 28, 2002 the trial court did not abuse its discretion by terminating defendant’s right to self-representation. At several preliminary hearings the defendant represented himself. Because of defendant’s history of misconduct in custody the trial court admonished defendant he could maintain his pro se, self-representation, status as long as he acted appropriately. The court instructed him that if he started spitting, urinating or causing a disruption in the courtroom will result in his loss of this status. Mr. Al Armein moved to recuse the judge alleging his racial bias, conspiracy with a prior judge and the prosecution and harassment against defendant. After the defendant used profanity in his argument, the court admonished him not to use language “better suited for a gutter” and instructed defendant “You are in a courtroom. You are going to act like a lawyer.…” The defendant blamed his profanity on his purported TS, which he described as the “cursing disorder.” The prosecution opposed Mr. Al Armein’s motion arguing defendant did not raise any legal ground and his bizarre and outrageous statements raised serious doubt about his competency to represent himself. When the court denied defendant’s motion to recuse, he stated, “I renew my motion for your recusal. You are one dirty, filthy, racist pig, your Honor. I demand your recusal. And I’m sorry if my Tourette’s syndrome acted up again.” The court stated that a person with TS does not have a premonition and ordered a competency hearing. At a subsequent hearing the court found defendant competent based on a psychiatrist’s report stating, “It appears that your conduct at the last hearing was not a result of mental illness or any organic disease. So it was intentional and planned. And in addition to that, it was outrageous; it was contemptible.” The court then terminated defendant’s right to self-representation. The appellate court found the trial court did not abuse its discretion by terminating Mr. Armein’s right to self-representation.

In another opinion State v. Jason Ryan Burford.77 the defendant appealed his conviction for murder. At trial a brief mention was made that during the search of defendant’s apartment, police found correspondence from Mensa indicating the defendant “had missed be admitted to that group of people with a high IQ because he was just one IQ short.” Defendant challenged the trial court’s decision to admit this evidence concerning enhanced intellectual capacity because he was not allowed to present evidence concerning TS, a disorder from which he suffers. The appellate court held that at trial the prosecution did not use defendant’s intellectual capacity to demonstrate his ability to plan or commit the crime. The appellate court then noted that evidence of diminished capacity, such as defendant wanted admitted concerning his TS, is expressly prohibited. The appellate court affirmed the defendant’s conviction.

Two cases, Timothy Purcell v. City of Philadelphia78 and Timothy Purcell v. Pennsylvania Department of Corrections79 show how a TS defendant was treated while incarcerated, either waiting for a trial or serving his sentence. In the first case, Mr. Purcell, a pretrial detainee, represented himself. He explained to the court that he suffered from TS. He complained that prison officials had failed to provide him with needed medical care. Unfortunately, without getting to the merits, the court dismissed this civil rights claim because it was overly broad. His second case more clearly highlights the misconstrued disabilities associated with TS. Mr. Purcell, a convict suffering with TS and comorbidities including ADHD, OCD, and coprolalia, had verbal and motor tics that were frequently characterized by “unpredictable attacks” of tics most severe under stress, anxiety or anger. His condition apparently impaired his ability to interact with others because his tics were often “unavoidable for him and often misunderstood and misconstrued.” It was also noted that stressful situations not only exacerbated his tics, requiring a release of built-up tics, but also led to decreased attention span and inability to concentrate. Mr. Purcell was authorized to have an “infirmary message” that permitted him to return to his cell, when needed, to release his tics and where he could be away from other inmates. Prior, Mr. Purcell had been allegedly subjected to “assaults by guards, inmates who did not understand Tourette’s.” In 1995, Mr. Purcell claimed discrimination by prison staff and submitted his written notice to the superintendent. He received a reply denying discrimination and furthermore was informed that he should “…stop using your Tourette syndrome as a convenient excuse to control your environment.” A second letter written by the superintendent stated, “We are not going to allow you to hide behind your Tourette syndrome diagnosis. You would use it to explain away your problems with the staff. You have got to learn that you are to follow lawful orders and not pick and choose using Tourette syndrome to explain your inability to do what is expected.” Later, Mr. Purcell was scheduled to have a follow up appointment with his psychiatrist and was instructed to report to the medical unit after leaving his daily Computer Aided Drafting and Design (CADD) class. After informing the prison officer that he was not well and needed to return to his cell to release built-up tics he had suppressed for 3 hours, he was again ordered to report to the medical unit. The prison officer charged him with misconduct for failing to obey an order. The prison hearing officer sentenced him to confinement to his cell for 30 days, without telephone access or group therapy sessions for 30 days. He was also permanently removed from his CADD course. Mr. Purcell’s claim of discrimination was granted and he was awarded punitive damages. The court concluded, “Much of this litigation was avoidable had the DOC realized the ADA applies to state penal institutions. Whatever the outcome of trial in this action, it should now be possible to reconcile institutional and inmate needs and avoid such litigation in the future.”

In conclusion, patients with TS may occasionally exhibit legally liable behavior, but the actual frequency of unlawful or criminal activity in TS is unknown. An understanding of the underlying neurobehavioral mechanisms that may predispose TS individuals to such socially unacceptable behavior is critical to the development of appropriate prevention, treatment strategies, and legal defense. Controlled studies designed to investigate the behavioral consequences of TS and comorbid disorders are needed. Insights into neurobehavioral mechanisms which influence problematic behaviors, and information on how such behaviors reach levels of illegality should also be pursued. Finally, programs designed to increase awareness within the professional legal community about TS and other neurobehavioral disorders are needed to provide guidance to the courts and the legal system on how to assess and respond to patients suffering from these disorders.

|

1 Abbott A: Into the mind of a killer. Nature 2001; 410:296–298Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Pincus J: Base instincts what makes killers kill? Norton, New York, NY, 2001Google Scholar

3 Treiman D: Violence and the epilepsy defense. Neurol Clin 1999; 17:245–255Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Mychack P, Kramer J, Boone K, et al: The influence of right frontotemporal dysfunction on social behavior in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2001; 56:511–515Google Scholar

5 Munkner R, Haastrup S, Joergensen T, et al: The temporal relationship between schizophrenia and crime. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003; 38:347–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Anderson S, Bechara A, Damasio H, et al: Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex. Nature Neurosci 1999; 2:1032–1037Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Raine A, Lencz T, Bihrle S, et al: Reduced prefrontal gray matter volume and reduced autonomic activity in antisocial personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:119–127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Laasko M: Psychopathy and the posterior hippocampus. Behav Brain Res 2001; 118:187–193Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Braun A, Randolph C, Stoetter B, et al: The functional neuroanatomy of Tourette’s syndrome: a FDG-PET Study. II: Relationships between regional cerebral metabolism and associated behavioral and cognitive features of illness. Neuropsychopharmacol 1995; 13:151–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Brower MC, Price BH: Neuropsychiatry of frontal lobe dysfunction in violent and criminal behaviour: a critical review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 71:720–726Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Soloff PH, Meltzer CC, Becker C, et al: Impulsivity and prefrontal hypometabolism in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2003; 123:153–163Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Shapiro A, Elaine E: Treatment of Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome with haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry 1968, 114; 345-350Google Scholar

13 Kurlan R, Como PG, Miller B, et al: The behavioral spectrum of tic disorders: A community-based study. Neurol 2002; 59:414–420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Jankovic J Tourette’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 2001, 345; 1184-1192Google Scholar

15 Spencer T, Biederman J, Coffey B, et al: T Tourette disorder and ADHD. In: Cohen D, Jankovic J, Goetz C (edds). Tourette Syndrome, Adv Neurol, Vol. 85, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2001: 57-78Google Scholar

16 Miguel E, Campos M, Shavitt R, et al: The tic-related obsessive-compulsive disorder phenotype and treatment implications, in Cohen D, Jankovic J, Goetz C, Eds. Tourette Syndrome, Adv Neurol, Vol. 85, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2001: 43-56Google Scholar

17 King R, Leckman J: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, and depression. In: Leckman J, Cohen D (eds). Tourette’s syndrome-tics, obsessions, compulsions. New York: John Wiley & Sons & Sons, 43-62Google Scholar

18 Coffey B, Park K: Behavioral and emotional aspects of Tourette syndrome. In: Jankovic J, Ed. Tourette syndrome. Neurol Cl N Am, WB WB Saunders, Philadelphia, Vol. 15, 1997: 277-290Google Scholar

19 Singer H, Wendlandt J: Neurochemistry and synaptic neurotransmission in Tourette syndrome, in Cohen D, Jankovic J, Goetz C, Eds. Tourette Syndrome, Adv Neurol, Vol. 85, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2001: 1163-1178Google Scholar

20 Singer H. Neurobiology of Tourette syndrome. In: Jankovic J, Ed. Tourette syndrome. Neurol Cl N Am, WB WB Saunders, Philadelphia, Vol. 15, 1997: 357-380Google Scholar

21 Rasmussen A, Eisen J: Epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51:20–23Medline, Google Scholar

22 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. DSM-IV. 4th edition, Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

23 Leckman J, Walker D, Goodman W “Just-right” perceptions associated with compulsive behavior in Tourette’s syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:675–680Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Miguel E, Baer L, Coffey B: Phenomenological differences appearing with repetitive behaviors in obsessive-compulsive disorder and Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:140–145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Comings D: Genetic factors in substance abuse based on studies of Tourette syndrome and ADHD probands and relatives. I. drug abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend 1994; 35:1–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Comings D: Genetic factors in substance abuse based on studies of Tourette syndrome and ADHD probands and relatives. II. alcohol abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend 1994; 35:17–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Gamberino W, Gold M Neurobiology of tobacco smoking and other addictive disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999; 22:301–312Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Schmidt L, Dufeu P, Heinz A, et al: Serotonergic dysfunction in addiction: effects of alcohol, cigarette smoking and heroin on platelet 5-HT content. Psychiatry Res 1997; 72:177–185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Lesch K, Merschdorf U: Impulsivity, aggression, and serotonin: a molecular psychiobiological perspective. Behav Sciences and the Law 2000; 18:581–604Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Brunner D, Hen R: Insights into the neurobiology and impulsive behavior from serotonin receptor knockout mice. Ann NY Acad Sci 1997; 836:81–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Dougherty D, Moeller F, Bjork J, et al: Plasma L-tryptophan depletion and aggression. Adv Exp Med Biol 1999;467: 57-65Google Scholar

32 Muller-Vahl K, Kolbe H, Schneider U, et al: Cannabinoids: possible role in patho-physiology and therapy of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 98:502–506Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Muller-Vahl K, Kolbe H, Schneider U, et al: Cannabis in movement disorders. Forsch Komplementarmed 1999; 6:23–27Google Scholar

34 Peterson B, Riddle M, Cohen D: Reduced basal ganglia volumes in Tourette’s syndrome using three-dimensional reconstruction techniques from magnetic resonance images. Neurology 1993;43: 941-949Google Scholar

35 Eidelberg D, Moeller J, Antonini A: The metabolic anatomy of Tourette’s syndrome. Neurology 1997; 48:927–934Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 Hollander E, Rosen J: Impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol 14(2 suppl 1):S39-44, 2000Google Scholar

37 Cardinal R, Pennicott D, Sugathapala C, et al: Impulsive choice induced in rats by lesions of the nucleus accumbens core. Science 2001; 292:2499–2501Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio A, et al: Different contributions of the human amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex to decision-making. J Neurosci 1999; 19:5472–5481Google Scholar

39 Peterson B, Skudlarski P, Anderson A: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of tic suppression in Tourette syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:326–333Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 Singer HS, Szymanski S, Giuliano J, et al: Elevated intrasynaptic dopamine release in Tourette’s syndrome measured by PET. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1329–1336Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Albin RL, Koeppe RA, Bohnen NI, et al: Increased ventral striatal monoaminergic innervation in Tourette syndrome. Neurol 2003; 61:310–315Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 Bruun R, Budman C: Paroxetine treatment of episodic rages associated with Tourette’s disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:581–584Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 Budman C, Bruun R, Park K, et al: Rage attacks in children and adolescents with Tourette’s disorder: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:576–580Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 Calder AJ, Keane J, Lawrence AD, et al: Impaired recognition of anger following damage to the ventral striatum. Brain 2004; 127:1958–1969Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 Kurlan R, Daragjati C, Como P, et al: Non-obscene complex socially inappropriate behavior in Tourette’s syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:311–317Link, Google Scholar

46 Teive H, Germiniani F, Della M, et al: Tics and Tourette syndrome: clinical evaluation of 44 cases. Ar Qneuropsiquiatr 2001; 59:725–728Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 Stern E, Silbersweig D, Chee K et al: A functional neuroanatomy of tics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:753Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 Brunner H, Nelen M, Breakefield X, et al: Abnormal behavior associated with a point mutation in the structural gene for monoamine oxidase A. Science 1993; 262:578–580Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 Seif I, De Maeyer E: Knockout corner: knockout mice for monoamine oxidase A. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 1999; 12:241–243Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Abelson JF, Kwan KY, O'Roak BJ: Sequence variants in SLITRK1 are associated with Tourette’s syndrome. Science 2005; 310:317–320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 Yen RJ: Tourette’s syndrome: A case example for mandatory genetic regulation of behavioral disorders. Law and Psychology Review, 29, West 2003Google Scholar

52 Freeman RD, Fast DK, Burd L, et al: Tourette Syndrome International Database Consortium. An international perspective on Tourette syndrome selected findingsfrom 3500 individuals in 22 countries. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2000;42: 436-447Google Scholar

53 Comings DE, Comings BG: A controlled study of Tourette syndrome. II. Conduct. Am J Hum Genet 1987; 41:742–760Medline, Google Scholar

54 Comings DE: Clinical and molecular genetics of ADHD and Tourette syndrome. Two related polygenic disorders. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001;931: 50-83Google Scholar

55 Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDD): Questionnaire content based on statistical analysis of juvenile crimes committed in 1999. http://ojjdp.ncjrs.org/ojstatbb/html7qa250.htmlGoogle Scholar

56 Devon B Adams, Lara E. Reynolds: Bureau of Justice Statistics 2002 at a Glance, NJC 19449, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Aug 2002Google Scholar

57 Equipped: U.S. Prisons and Offenders with Mental Illness. ISBN: 1564322904, Human Rights Watch, 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor, New York, NY 10118-3299, Sept 2003Google Scholar

58 Stewart M, Cummings C, Singer S, et al: The overlap between hyperactive and unsocialized aggressive children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1981; 22: 35-45Google Scholar

59 Gittelman R, Mannuzza S, Shenker R, et al: Hyperactive boys almost grown up. I. Psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42: 937-942Google Scholar

60 Siponmaa L, Kristiansson M, Jonson C, et al: Juvenile and young adult mentally disordered offenders: the role of child neuropsychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2001; 29:420–426Medline, Google Scholar

61 Chuck Jeffords, Research Director, Tex. Youth Commission, 4900 N. Lamar Blvd, Austin, Tex. 78751Google Scholar

62 United States v. Sweeting, 213 F3d 95, 13 Fed.Sent.R. 291, 3rd Cir. (Pa.), May 3, 2000.Google Scholar

63 United States v. Sassani, 139 F3d 895, 1998 WL 89875, 4th Cir. (Md.), March 4, 1998.Google Scholar

64 United States v. Rigatuso, 719 F.Supp. 409, D.Md, July 18, 1989Google Scholar

65 People v Mootry, 2003 WL 22351895 (Cal.App. 4 Dist), Oct 16, 2003Google Scholar

66 Smith v. State, 88 S.W. 3d 652, TXApp.-Tyler, April 3, 2002Google Scholar

67 State v. Hutchins, 2001 WL 04365, Iowa App, July 18, 2001Google Scholar

68 State v. Hunter, 303 Mont. 539, 18 P. 3d 1033 2000 WL 1877764, 2000 MT 376N, Mont, Dec 28, 2000Google Scholar

69 In re A. D. V., 1999 WL 1243287, TXApp.-Austin, Dec 23, 1999Google Scholar

70 Brown v. State, 751 So. 2d 1155, MSApp, Sept 7, 1999Google Scholar

71 State v. Simpson, 946 P. 2d 890, Alaska App, Oct 10, 1997Google Scholar

72 United States v. Hall, 93 F3d 1337, 65 USLW 2195, 45 Fed.R.Evid.Serv. 1, 82 A.L.R. 5th 801, 7th Cir. (Ill.), Aug 27, 1996Google Scholar

73 United States v. Dzialo, 773 F.Supp. 21, E.D.Mich, Sept 13, 1991Google Scholar

74 People v. Michael Lempicki, 2002 WL 737980 ( Mich.App.), April 23, 2002Google Scholar

75 United States v. Santo Rigatuso, 719 F.Supp 409(USDC Maryland 1989), July 18, 1989Google Scholar

76 People v. Almed Al Armein, 2002 WL 1060849 (Cal.App. 4 Dist.), May 28, 2002.Google Scholar

77 State v. Jason Ryan Burford, 2001 WL 641441 (Minn.App.), June 12, 2001Google Scholar

78 Timothy Purcell v. City of Philadelphia, 1987 WL 6322 (E.D.Pa.), Civ. A. number 86-7534, Feb 6, 1987Google Scholar

79 Timothy Purcell v. Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, 1998 WL 10236 (E.D.Pa.), number CIV. A. 95-6720, Jan 9, 1998Google Scholar